Introducing the July Issue

Trudy Lieberman reports on the failed promise of the Affordable Care Act, Sarah A. Topol explores Ukraine’s struggle for a national identity, Dave Madden spends a week in Hollywood’s toughest comedy club, and more

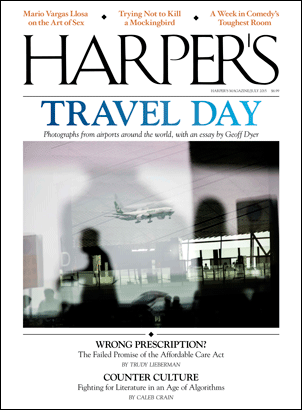

Airplane travel used to be a luxury, a privilege enjoyed only by the elite, a reason to dress up. Now, a trip to the airport is an inconvenience at best. As evinced in this month’s Folio—a collection of images from airports in Mumbai, Paris, Panama City, Lagos, and elsewhere—today’s travelers err on the side of comfort rather than elegance, sleepily awaiting their flights in sweat suits. “If airports,” writes Geoff Dyer in his accompanying essay, “were once places to which one made occasional and thrilling visits, now many of the people encountered in them have the look, in prison parlance, of ‘lifers.’” In documenting the terminals, baggage claims, moving walkways, and bars at modern airports, the photographs reveal that much about air travel has changed since the Sixties and Seventies—cell phones, for example, have replaced cigarettes. But, writes Dyer, “the essential human dramas remain unchanged.” Also revelatory: the unexpected beauty our photographers managed to capture in these crowded, industrial spaces today’s travelers have come to dread.

Airplane travel used to be a luxury, a privilege enjoyed only by the elite, a reason to dress up. Now, a trip to the airport is an inconvenience at best. As evinced in this month’s Folio—a collection of images from airports in Mumbai, Paris, Panama City, Lagos, and elsewhere—today’s travelers err on the side of comfort rather than elegance, sleepily awaiting their flights in sweat suits. “If airports,” writes Geoff Dyer in his accompanying essay, “were once places to which one made occasional and thrilling visits, now many of the people encountered in them have the look, in prison parlance, of ‘lifers.’” In documenting the terminals, baggage claims, moving walkways, and bars at modern airports, the photographs reveal that much about air travel has changed since the Sixties and Seventies—cell phones, for example, have replaced cigarettes. But, writes Dyer, “the essential human dramas remain unchanged.” Also revelatory: the unexpected beauty our photographers managed to capture in these crowded, industrial spaces today’s travelers have come to dread.

“Five years after its passage,” writes Trudy Lieberman in her Report on the failed promise of the Affordable Care Act, “the A.C.A. . . . is still shrouded in a fog of controversy.” In her investigation of why that is, Lieberman makes some grim discoveries. The A.C.A., Lieberman writes, is hardly the “vehicle for delivering universal health care” it was sold as; instead, it’s a “canny restructuring of the American health-care marketplace, one that delivered millions of new customers to insurance companies.” One of the law’s first consequences: it has accelerated the transfer of medical costs to the patients themselves, a phenomenon she calls the Great Cost Shift. While the law has, to its credit, lowered the number of uninsured Americans, made it possible for the sick to buy insurance, and allowed more of the country’s very poorest to access Medicaid, the unfortunate fact remains that “in the post-A.C.A. era, you can be insured but have little or no coverage for what you actually need.”

Sarah A. Topol’s Letter from Ukraine begins at the National Memorial Museum Dedicated to Victims of Occupational Regimes. Located on Lontskoho Street in the city of Lviv, the museum is housed in a former prison that, “like just about every building, street, town, and city in Ukraine . . . has changed hands many times during the past century.” Topol, whose first language was Russian (her mother was born in Kiev, now within Ukraine’s borders), isn’t, by her own admission, interested in “historical truths.” Instead, she’s fascinated by “the way in which Ukrainians interpreted their own history and identity following the collapse of the U.S.S.R.—especially in the wake of Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March 2014” and the subsequent formation of two secessionist republics in Donetsk and Lugansk. What Topol finds is a country divided—again and again—against itself. “If every group in Ukraine builds its own museums and publishes its own history books,” she wonders, “why would anyone feel loyalty to the center?”

“There’s no bar at Marty’s and no kitchen. The club is open six evenings a week, from five to eleven o’clock. The only thing to do there is to watch open-mic stand-up comedy or get onstage and perform it.” For an entire week, Dave Madden hung out at Marty’s—“the world’s bleakest comedy club”—and did just that. What he sees is not pretty (or funny, for that matter). One comic jokes: “I blame the Boston bombings on the hairy nipples of the gay and lesbian, overweight, black and Jewish midget pornographers of Islam.” Another talks about barely avoiding prison rape; a third describes a Facebook flame war. These are comedians “unwilling or possibly unable to tell jokes in the standard setup–punch line format. Their sets,” Madden observes, “often sounded less like comedy than like the stories of everyday tragedy a person might hear in an A.A. meeting.” But it’s when Madden finally gets up onstage to perform his own set—and bombs—that he understands the utility of a place like Marty’s: comics can “work through their discomfort—in public and over many hours,” in the hopes of appearing “natural and true.”

Also in this issue: a broadside against digital culture by Caleb Crain; a meditation on the science of human happiness by Kristin Dombek; previously unpublished fiction by Clarice Lispector; reviews of Linda Rosenkrantz’s Talk, Christy Wampole’s The Other Serious: Essays for the New American Generation, and Downtown Film and TV Culture: 1975–2001 by Christine Smallwood; and an excerpt from Seth Price’s new novel, Fuck Seth Price.