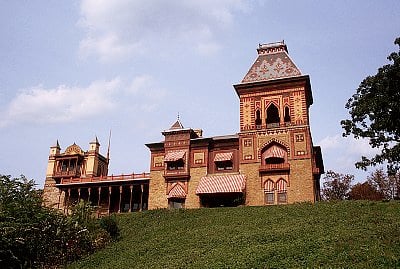

There is a Moorish mansion on a steep hill in the New York countryside. Built by the landscape painter Frederic Edwin Church, it has mosaic rooftops, mortared stone walls, and a fez-red trim. Its balconies look out through horseshoe archways at the Hudson River Valley from a boxy, upright structure of a kind that is more locally familiar than its trappings; in fact, it’s a Victorian in Orientalist drag.

To get inside you have to take the tour. They sell the tickets at the gift shop in the carriage barn, a building just below the hilltop, painted solid green in deference to the house. I went in spring on no occasion. The silent man behind the register declined my press credentials, looking at them like they were reminding him of something he’d forgotten, so I paid. We were early. He invited us to watch their documentary. We followed him to a sunny back room full of benches that felt like a frontier chapel. A television on a rolling stand was displaying credits. The video ended and started over.

Church had muttonchops, a bare chin, and a wide-eyed visionary look that seemed to me, 150 years or so his junior watching photos of him passing on the screen, a little funny in its gravitas. The sun set on the house he built, or rose, above some treetops swaying in impressionistic VHS. Then there were images of Isabel, his wife; their children—the first set, who died; the second set, who would grow old at home—and zooming pans across photos of his paintings. Church was not alone, I thought, among the landscape painters of the nineteenth century in thinking that this was a country of volcanoes where the air was always full of mist. A family with a shivering Chihuahua entered as the movie finished.

Outside, someone walked a chocolate Lab. The Hudson, I was thinking, flows past here toward Manhattan, where I wonder if the art-world people know who Church was—do they think about the art celebrities who were contemporaries of their great-grandparents? I do not, in general.

Before the tour, we waited in a room between a wooden crate of pillows and a shelf of cheese accoutrements made by a company I recognized from Brooklyn. I was just arriving at the realization that the price of forty dollars for a dyed-wool pillow that I wanted probably referred to just its cover, when the guide began to speak.

“Church would be turning over in his grave if you thought the house was the only part of Olana. Olana is his masterpiece, a 3-D landscape artwork with more than five miles of carriage roads. How long do you think it took him to build?” He turned toward a child of maybe twelve. “A while,” the child replied. “A while!” the tour guide said. “How diplomatic! You must go to public school.” The alarm went off on a cell phone in his breast pocket, and he fished it out, apologizing. Then he elaborated: “I went to public school, too.”

We followed him up the carriage driveway to the house. It was baroquely decorated with designs in painted stencil, brick, and tile around its upper stories, with the rough facade dramatically left blank, its stones arranged so that their colors matched the patterns overhead. We gathered underneath the pseudo-minaret, whose windows were recessed behind an ornamental arch. Above the door, against a backlit pane of yellow bottle glass, there was a word in Arabic. This we were told meant “welcome,” by a different guide, who called us in.

It was a carpet-path tour. The quiet drawing room was full of paintings hung salon-style. Now our fresh-faced guide stood speaking of one in an upper corner, a study, he told us, for Church’s The Heart of the Andes, which was the piece that had made the artist a celebrity. In 1859 it was displayed in New York City, where each visitor paid a quarter to see it. I stood looking up at the study, a small brown canvas, trying to imagine how those people saw it then. And I could see, at least, that it was a mountain scene, having a kind of heavy, highland feeling; in the background, with its bottom half in fog there was another snowy peak. Here’s the drama, I thought: A viewer meets the “heart” as one who has just arrived, still in the distance. And the tiny Christian grave attended by two figures in the foreground is supposed to speak to what was sacrificed to get there. I looked down. The subject matter looked about the same to me in all the other paintings in the room: an infinite green wilderness, aurora, everything reflecting in a lake; apocalyptic black skies, ruins, fire; in the corners, single Indians, conquistadors in metal armor.

I had found Olana on the Internet, like everybody else there probably had too, and in the hall beyond the drawing room we met a scene I was especially aware I’d already encountered multiplied in slightly different colors in the search results. A pointed archway and a pair of drawn-back curtains framed the central staircase, where a metal Buddha sat surrounded by ceramic vases. On the lower landing flanked by inward-facing metal storks, there was a table with a coat of arms, a velvet couch, blue China on display stands, and a taxidermied peacock. Here the guide began to ask if we saw anything unusual about the glowing yellow window in the back, but stopped himself abruptly to declare it was a question that he usually asked later.

When the time came, we would learn that what was strange about this window, which appeared to be stained glass, was that its diamond-patterned grille was sagging at the edges; it was made of paper. “Church cared more about appearances than authenticity,” we were informed. From the hall we filed into a narrow private study, where the walls were bordered with a script I thought was Arabic, but when I asked its meaning, I was told that it was nonsense Church invented, because he liked the way it looked. “Church was not a portrait painter, but here’s one of Isabel,” the guide said, pointing out a portrait in three-quarter profile of the artist’s wife against a murky background. “Only close friends would have been invited to this room.” Above the fireplace there was a pink view of some columned ruins. In the decades when Olana was constructed, Church’s popularity declined, according to our guide, because of the Impressionists; this painting represented an attempt to stay contemporary.

On the balcony, the people photographed themselves, and one another, and the view. The view is under restoration, read an empty Plexiglas collection box. There were a few stumps on the hill, and down below, the Hudson glittered, cutting through the valley’s rolling forest. “How long has that factory been there?” an old man asked, pointing at some smokestacks on the river in the distance.

“Since at least the lives of Church’s children,” said the guide.

“What happened after that?” the old man asked.

“They died,” the guide said, ushering the group back in, toward Church’s studio. “The house was handed over to the state.”

I looked down at the factory, the shoreline houses, and the bridge, whose name I knew to be the Rip Van Winkle; I had crossed it after taking a wrong turn that day. “I took the Rip Van Winkle Bridge by accident,” I whispered to myself, and went inside.

“We’re fortunate that Church’s heirs lived in Olana like it was already a museum,” the guide announced. “As far as we know, this studio is exactly as he left it.” He had left it clean and empty. Lit from three directions, it was furnished like a living room, with fireplace and daybed. Tasseled chairs sat angled toward each other near a floor-to-ceiling pane that faced the valley.

“In the end, Church worked here less than he’d expected,” said the guide. I looked around. The decorations felt uncertain, vaguely careless: desiccated starfish hanging from the molding by a table full of hats in no particular arrangement. And the window, with its yellow-patterned border curving at the top to form a pointed archway in the glass, resembled an illuminated page. There was an empty easel with a palette; shelves of art supplies; a painting by the artist’s mentor, dim; a case of carved-stone artifacts collected on a trip to South America. “Some of those objects are authentic, others made for tourists,” said the guide. “Church didn’t care.”

We moved on through a few dark halls back toward the entryway, and then through something that the guide referred to as the only European room: a cold, wide dining area with wainscoting. “Church’s children had a rotating exhibition of the family collections here,” he said. Quattrocento imitations hung along one wall beside a wooden table and a spiky, dark-green potted plant that kept it company, together looking like a campsite in the empty space. I wondered who had moved the paintings for these heirs, perhaps fed them their dinner as the light fell, as it was now in the windows overhead. We walked out past a roped-off library, a windowless enclosure that to me was reminiscent of the siege room in the Alamo. A lime-green lightbulb had been turned on in the foyer, and the tour concluded with an explanation of it: “This is ten times brighter than it would have been when it was lit with gas, when Church and Isabel lived here.”

A corridor of doorways had been opened through the middle of the house, so that from here the glowing picture window in the studio was framed by one after another nesting arch. I thought about the painting in the drawing room, its image of arrival at the mountains’ heart revealing further mountains, and about the densely decorated staircase to the unseen upper floors. It seemed the things that people spoke about as Church’s masterpieces shared a structure of successive revelations with no final object. Looking back at all the piled-up carpets and the tasseled pillows on divans, I wondered if this underlying structure was inspired by what Church and his contemporaries would have called an arabesque: an open-ended pattern that supposedly evoked the infinite through the indefinite. It was this idea with which the Orientalists had mystified a range of decorative styles that might in fact have had no more in common than their geometric open-endedness.

Now the front door opened. It was lighter out than I’d expected.