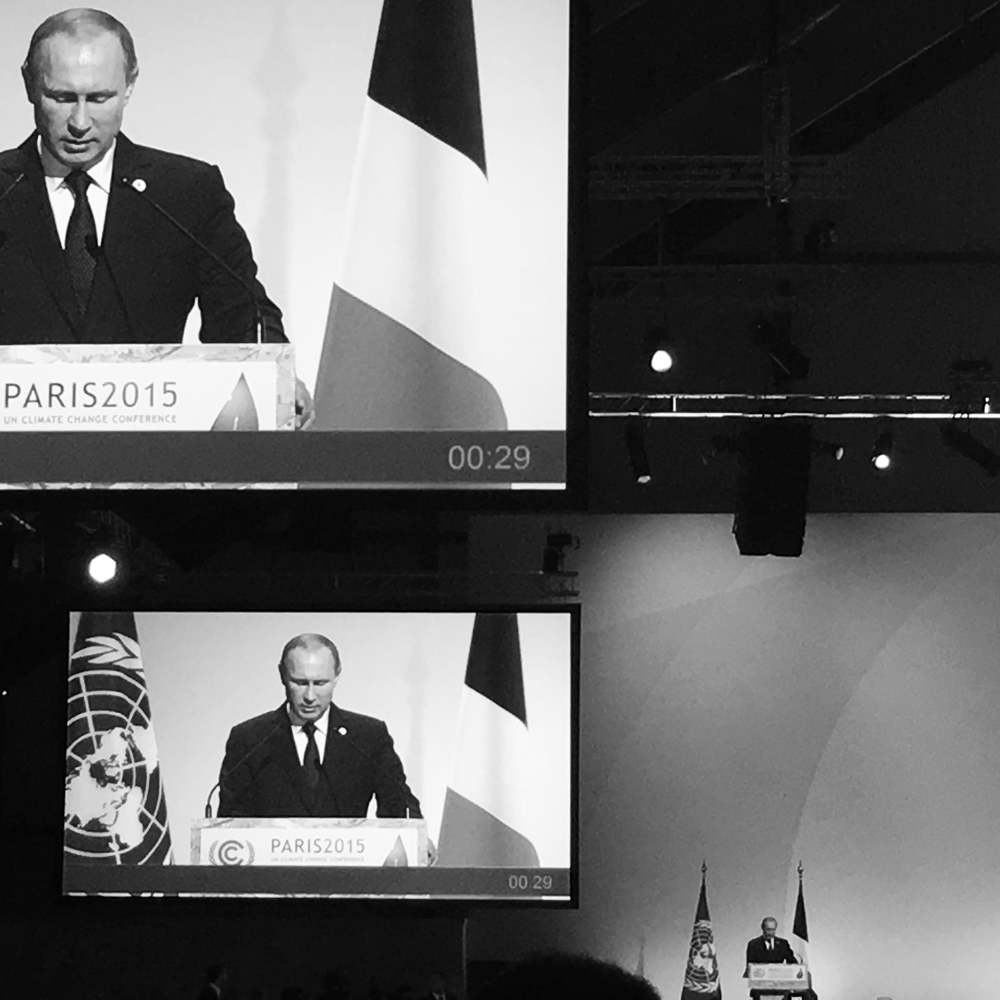

Russian president Vladimir Putin speaking at the Paris climate summit. Photograph by Darren Aronofsky

On Monday, the twenty-first session of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change—also known as COP21, or the Paris climate summit—kicked off in a grand conference hall in Le Bourget, France. Through a lot of running around, a little pleading, and the special skills of the Brooklynese—in this case, filmmaker Darren Aronofsky, moonlighting as my Harper’s photographer—I was among the few reporters allowed inside to watch half the world’s leaders give their opening statements. It was amazing to be in that room with Xi Jinping, Vladimir Putin, Angela Merkel, and Barack Obama—quite possibly the four most powerful people on earth—along with U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, Framework Convention Executive Secretary Christiana Figueres, and dozens of other world leaders.

It was amazing and often also boring. The statements were largely positive, predictable, vague, and repetitious. Of course, world leaders have to be graded on a curve. Putin’s statement at least recognized the reality of climate change and suggested that we should do something about it, which is an improvement over his record of denying and dismissing the problem. Obama spoke of his summer trip to Alaska, whose melting permafrost and burning tundra are “a preview of one possible future”—though it’s the present, not the future, for Alaska. Still, Obama did acknowledge one of the central facts of the day: “We know the truth that many nations have contributed little to climate change but will be the first to feel its threats.”

Given this fact, it’s no surprise that things got real when some of the less famous world leaders took their turns. Egyptian president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi noted that Africa is both the continent that emits least per capita and the one that faces the gravest consequences. Ismaïl Omar Guelleh, the president of Djibouti, itemized the ways his region would be destroyed, and is being destroyed now. “It is clear that if nothing is done,” he said, “the peoples of East Africa will find it impossible to survive.”

Later, in a much smaller room, with far less fanfare, members of the group of climate-vulnerable nations met. These included places like Nepal and Bangladesh, Ethiopia and Afghanistan, as well as the forty-four-nation Alliance of Small Island States. As Philippines president Benigno Aquino III noted, “vulnerable countries bear more than half the economic impact and 80 percent of the health impact” of climate change and are “losing 2.5 percent of GDP to climate [change] each year.” Few places are more imperiled than the archipelagos of the Philippines; he mentioned 50,000 deaths per year since 2010 in climate-related incidents and 40 million people facing displacement in the foreseeable future.

While the official goal of the conference is to keep climate change within 2 degrees Celsius of preindustrial levels, the vulnerable nations have called instead for a goal of 1.5 degrees. The same demand for 1.5 degrees was made at the failed Copenhagen climate conference six years ago. Since then the Philippines has been racked by brutal storms. The glaciers of the Andes and Himalayas have accelerated their melting, as have those of Greenland and Antarctica, contributing to sea-level rise. All those climate events mean suffering, death, and the transformation of long-inhabited places into uninhabitable ones.

The 1.5-degree manifesto came with a proposed hand signal—a pinky finger (one) jutting from a fist (the degree point) and five fingers on the left hand outstretched—that participants can hold up during the deliberations. It’s painful that little solidarities and signals like this are being looked upon to save people from, to put it baldly, burning and drowning. The manifesto, to which every participant nation in the room agreed, may play a major role in the conference: either by helping to push other nations to make an ambitious commitment, or by setting a goal that others are unwilling to meet. “We refuse to be the sacrifice of the international community in Paris,” said Bangladesh’s environment minister.

The difference between 1.5 and 2 degrees may seem academic; however, while even the latter is a goal we will have to work hard to achieve, the former means the difference between apocalypse and survival in many parts of the world. What is needed is for all nations to commit to substantial emissions reductions now and to ratchet up those commitments in the future. This seems viable as both climate science and climate engineering grow more precise—knowledge of how, for example, farming can become a means of carbon sequestration (pulling it out of the atmosphere and putting it back in the ground, where we’ve been taking it from these last 200 years) seems to be a promising indicator that we will be able to make increasingly good and sophisticated decisions. On this front, the European Union has made a dramatic commitment—cutting emissions by 40 percent, to below 1990 levels. Russia and the United States have chosen 2005 as their benchmark instead. For a framework that began in 1992, 2005 is a lousy benchmark; it’s like a person who’s gained a hundred pounds deciding that losing the last fifty will get the job done. But the United States seems to have made the calculated decision that getting back to its 1990 weight would just be too painful.

Many Americans first learned of the kind of cold-blooded cost-benefit analysis the powerful routinely make with our lives in 1977, when journalist Mark Dowie revealed that Ford Motor Company had been knowingly selling exploding Pintos for nearly a decade. The company had done some calculations and determined that it made more financial sense to pay out damages on several hundred fiery deaths than to spend an additional $11 per car to prevent them. A new round of investigative journalism has revealed that ExxonMobil is prepared to accept vast long-term loss—not in terms of quarterly returns, of course, but in terms of a large percentage of all species, millions of people, and several dozen nations. That corporation, through its research scientists, knew in detail about climate change decades ago and decided first to keep quiet and then to run campaigns to discredit that science. When it comes to climate change, we are all—carbon companies, world leaders, and, to a lesser extent, you and me—making similar calculations, doing the moral equivalent of continuing to manufacture death traps.

The passionate Figueres spoke toward the end of the vulnerable-nations meeting to remind all of us what this conference means. She said, “The countries around this table are going to determine whether we have an ambitious agreement or just have an agreement. And that difference is a key difference. The quality of the Paris agreement equals the quality of life for the most vulnerable.” Or the quantity of death.