Frozen World

A visit to the American Museum of Natural History's frozen-specimen collection.

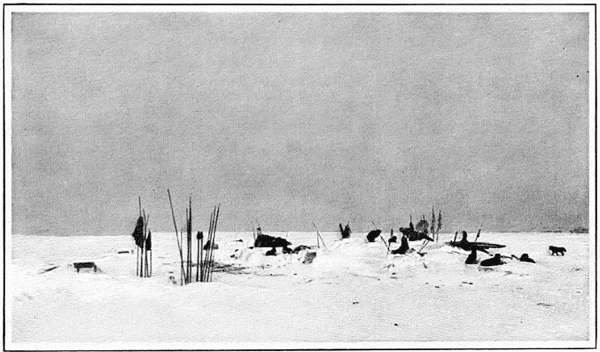

A Camp on the Shore of Victoria Land, originally published in the March 1913 issue of Harper’s Magazine.

Noah built a boat to preserve the world’s biodiversity; today, scientists build freezers. In the underbelly of Manhattan’s American Museum of Natural History, I meet Julie Feinstein, the director of the Ambrose Monell Cryo Collection. I think we are somewhere beneath the Hall of Minerals or of Meteorites but, after the bewildering number of twists and turns we’ve taken—through the museum’s exhibits and down into storage facilities and then across the shipping room—it’s hard to tell for sure.

Feinstein’s laboratory is one of the museum’s hidden marvels. Among the world’s largest cryogenically frozen-tissue-sample collections, it exists in a tiny basement on the building’s western edge, near the corner of West Seventy-Seventh Street and Columbus Avenue. Not far from where we are standing is a 3,000-gallon liquid-nitrogen tank surrounded by eight-foot fences with six-inch metal spikes on top. The tank feeds liquid nitrogen into stainless steel vats inside the laboratory, and in these vats rest 100,000 organic samples—little pieces of whales and birds and monkeys and other nonhuman species taken from around the planet and now kept frozen at minus 160 degrees Celsius.

Around 10,000 samples have been added to the Ambrose Monell Cryo Collection each year since it was built in 2001, and it has the capacity to hold one million. The samples are the foundation of the museum’s efforts to map the evolutionary relationships among organisms through their genetic makeup, and many of the specimens are exceedingly rare: highly endangered Channel Island foxes; a nautilus from Vanuatu, in the South Pacific; leopard frogs from the Huachuca Mountains. Lepidopterologist Dan Janzen’s life’s work—samples from forty years of butterfly collecting in Costa Rica—is housed in the collection. So is some of the stock of tissue samples collected by the U.S. National Park Service, including California condors and endangered Karner blue butterflies.

It is difficult to imagine the treasures the steel canisters hold, and I ask Feinstein, a botanist by training, whether I can look inside one. She puts on plastic goggles and thick rubber gloves and steps onto a small platform connected to the six-foot vat. As she opens its lid, a thick white fog spills over the sides. Inside the vat it’s cold enough to freeze a piece of fruit so solidly that it would smash like glass.

Feinstein invites me to step onto the platform, warning me not to inhale the vapor too deeply. I see inside the vat what looks like a giant Trivial Pursuit pie with six sections; each section holds nine metal racks. With a gloved hand, Feinstein turns the pie and pulls a rack out, revealing thirteen white boxes stacked one on top of the other. Inside each box are a hundred two-inch vials, each labeled with a bar code and serial number. Using forceps, Feinstein picks one from a box at random. “This is number 110029,”she says, reading the bar code.

We walk to her office in the next room, and she opens up the collection’s database on a computer. “Here it is,”she says. “110029 is a mosquito from the New York City Department of Health.”We laugh. From a collection whose mission is to be the largest and most comprehensive array of genetic diversity of life on the planet, Feinstein has randomly picked a sample that might have been plucked from a puddle not far from where we are sitting.

One of the first individuals to recognize that the world’s genetic diversity was in need of saving was an Austrian geneticist and plant breeder, Otto Frankel. Born in 1900, Frankel was a young Communist who came to be known as the prophet of genetic-resources conservation in the 1960s. Frankel believed that humankind’s impact on genetic diversity was on so great a scale that we had “acquired evolutionary responsibility” and must develop what he called an evolutionary ethic. “Genetic wildlife conservation makes sense only in terms of an evolutionary timescale,”he said in 1974. “Its sights must reach into the distant future.”

A year after Frankel delivered this message in Berkeley, several biologists at the San Diego Zoo began collecting and freezing tissue samples of wildlife for what they called the Frozen Zoo.They cryopreserved sperm, eggs, and embryos from rare individuals to be used in an array of assisted reproductive techniques. Since its inception, the Frozen Zoo has gathered tissue samples from more than 10,000 animals representing over 1,000 species, and as scientists create ever more sophisticated technologies to use in assisted reproduction and cloning, the collection has become a freezer from which scientists hope entire animals can be resurrected.

Just over forty years after Frankel’s call for the development of an evolutionary ethic, the cryopreservation of the world’s biodiversity is in considerable fashion, the enthusiasm for preserving genetic materials akin to the nineteenth-century zeal for herbariums, zoos, and natural history museums. In 2011, the Smithsonian Institution began building a new facility with the capacity to preserve 4.2 million specimens. The International Barcode of Life project is a consortium of genetic repositories whose goal is to create 5 million barcode records from the DNA of 500,000 species. The Genome 10K Project is collecting tissue and DNA samples from about 17,000 species in order to sequence 10,000 genomes for analysis; the announcement of the initiative called it the biggest scientific study of molecular evolution ever proposed. There are now hundreds of frozen genetic banks around the world holding samples that provide snapshots of moments in history that might otherwise be lost: frozen water samples of a wetland might reveal microbes that are critical for restoring the ecosystem a hundred years from now.

In an era of anthropogenic global warming, preserving life in man-made freezers is both prudent and ironic, not a solution in and of itself, but a last resort. Consider the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. For generations, the Norwegians have referred to Svalbard, a frozen archipelago in the Arctic Circle, as ultima Thule, “the ends of the earth.”But in 2008, the Norwegian government blasted the permafrost of Svalbard in order to build a doomsdayvault designed to hold and preserve millions of seeds representing the world’s agricultural genetic diversity. Like the Frozen Zoo, the Cryo Collection, and other gene repository initiatives around the globe, the vault in Svalbard is designed to last far into the future, until a time when scientists will have miraculous uses, now impossible to predict, for its holdings.

Over the course of a few months, I make several visits to the Cryo Collection, and every time, after I leave the laboratory, I visit the upper floors of the museum to look at the exhibits. Standing in front of the fossils of extinct species—ambiguous dogs and ruminant horses—I try to focus my thoughts on the transience of so many life forms and the significance of the phenomenon of extinction. In the Wallace Wing of Mammals and Their Extinct Relatives, I look at dimly lit dioramas of African mammals, and it strikes me that the instinct to freeze these scenes of wildlife in time isn’t so different from the instinct that created the collection in the basement beneath me. The visionary behind the Hall of African Mammals was Carl Akeley, a biologist, big-game hunter, taxidermist, and photographer whose obsession was Africa. Akeley believed that he had to preserve the continent’s charismatic giraffes, lions, and rhinos, in order to draw attention to the disappearance of the African landscape. “The old conditions, the story of which we want to tell,”he wrote in 1926, “are now gone, and in another decade the men who knew them will all be gone.”

To the modern eye, gorged on IMAX, Akeley’s dioramas seem a little dispirited and artificial. But at the time they were revealed to the public, they were considered the height of realism. In the decades following his death, Akeley’s fears about Africa’s wildlife were realized. There are fewer than 900 mountain gorillas in the wild. Northern white rhinos are down to three. Lions have lost 90 percent of their range. But Akeley’s animals are still frozen in time, preserved for future generations to look at.

The Cryo Collection collapses space and time into two-inch vials—I don’t know if what I’m looking at is a whale or a mosquito—but it isn’t so different: both are acknowledgments that time is slipping by, sometimes so fast we have to hit the freeze button before things disappear.

This article is adapted from M. R. O’Connor’s book Resurrection Science: Conservation, De-Extinction, and the Precarious Future of Wild Things, from St. Martin’s Press.