As we approached the shore of Lake Ihema, Eugene Mutangana slowed the Land Cruiser to a stop. Our boat would be arriving soon, he said. Mutangana, the head of law enforcement at Rwanda’s Akagera National Park, had agreed to help me search for Mutware, an infamous ten-foot-tall African elephant who had lived in the area for decades. These days he spends much of his time camouflaged in the brush surrounding the lake. “I wish it would shine,” said Mutangana, looking up in vain for the sun amidst a thick wall of clouds. “When it shines, it leaves bush and comes to water.”

Akagera is home to giraffes, zebras, pythons, hyenas, and a myriad of other fauna. But this morning, apart from a few monkeys we spotted on the road, the park appeared calm. Mutangana nodded toward a few picnic pavilions thirty yards away. One of the green sheet-metal roofs was torn to shreds. “Mutware, at times, is very naughty,” he said.

Mutware wasn’t always so violent. Gaël Vande weghe, the son of a prominent Akagera researcher, was a toddler when he first met the elephant, which was then only the size of a sedan. As Vande weghe got older and continued to wander the park, he often crossed Mutware’s path. The elephant stuck close to the humans who fed him, a relationship that perhaps became too comfortable. “This elephant didn’t know his boundaries,” Vande weghe told me last April at a café in the Rwandan capital of Kigali, emphasizing that Mutware was a known thief. “He would take whole packs of cigarettes and [then] spit the lighter,” he said. Over the years, the antics escalated. In 2005, Mutware destroyed three vehicles, prompting the U.S. State Department to issue an alert warning Americans to “exercise extra caution when visiting the park.” Incidents like these only served to bolster Mutware’s fame—and infamy. He’s now an Akagera icon.

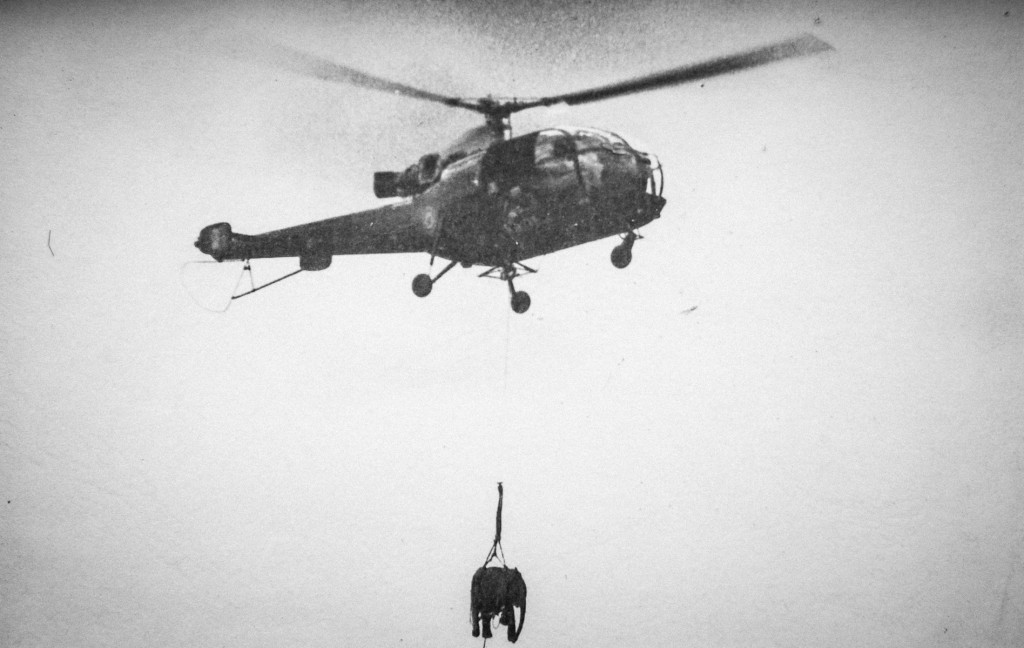

A young elephant being transported by helicopter to Akagera in 1975 from Bugesera district. Photograph by Jacky Babilon.

Mutware’s notoriety is born of a painful past. None of the dozen or so people I’ve spoken with about Mutware—whose name in Kinyarwanda translates to “chief”—seem to know his full history. But most tellings begin in the mid 1970s when settlers from Kigali were expanding into the nearby Bugesera swamps; land that was already occupied by Mutware’s herd of elephants. When the animals began raiding crops, authorities decided to kill all the elephants over the age of about eight and airlift or float the twenty-six remaining calves east, to Akagera. Mutware and two females were among the first batch of orphaned elephants to reach the park. There, a keeper named Bonifice Zakamwita raised them on porridge and sugarcane.

Domesticated life was never particularly good to Mutware. Vande weghe remembers people routinely abusing the young pachyderm, taunting him and chasing him with nail-filled boards. But humans also offered a steady supply of food and treats like bananas or cassava. On April 7, 1994, Mutware’s life changed again, when Hutu militias began targeting the Tutsi minority living in Rwanda. Over the next hundred days, as many as one million people were killed. In the aftermath of the genocide, coping with chaos became the norm for Rwanda, and Akagera was no exception. Thousands of returning refugees set up camp in the largely unguarded park, many looking to reestablish their cattle-farming tradition. The mix of people and wildlife was explosive. Lions began preying on cattle. Farmers retaliated by killing off the entire population. Depending on the telling, Zakamwita, a Hutu, either fled to Tanzania for safety or was imprisoned for perpetrating genocide. Regardless, Mutware was left to fend for himself.

“Since ’94, it started its own life,” said Mutangana. Alone and hungry, at first Mutware tried to rejoin the other elephants, but it didn’t go well. Mutangana told me he believes the herd rejected Mutware, who likely lost his tusks in clashes with stronger bulls. Forced back toward humans, this time Mutware decided to take what he wanted. “You can imagine how much he can eat in an overnight,” Mutangana half chuckled and half bemoaned. He pointed off the side of the boat to a sorghum field, which he says is one of the elephant’s favorites.

Today, the job of keeping Rwanda’s elephant chief under control falls to Akagera Management Company, a partnership between the governmental Rwandan Development Board and the nonprofit organization African Parks. They took over the management of Akagera in 2010, and visitor numbers have more than doubled since, to about 32,000 last year. The other major change has been the building of a roughly-seventy-five-mile-long fence along Akagera’s Western boundary. “It was for reducing animal-human conflicts,” Mutangana said of the 2013 project. “Mutware inclusive, definitely.” As an added measure, an eight-thousand-volt electric fence surrounds most buildings around the elephant’s main haunting grounds.

“This last year was more calm,” said Ian Munyankindi, who manages the Ruzizi Tented Lodge, which is situated on the shore of Lake Ihema. Mutware’s rampages have become less frequent—although he’s still known, on occasion, to grab a log, knock down the electric fence, and stroll through. “It’s like a human being in a body of an elephant,” said Munyankindi. “It’s a victim,” he added, “Bad or good, it’s human beings’ mistake. He is who he is because of us.”

By mid morning our boat had arrived and taken us to a ranger station on the south end of the lake, where Mutware was last seen. Disembarking, we walked over an embankment and past a small utility outpost, encircled by the requisite electric fence. “Yesterday it was here,” said Mutangana. Except for the sound of a few agitated hippos in the distance, the area now was quiet. Just past the fence, where the path turned into a loosely defined road, Mutangana stopped at an indent in the ground. The elephant, he surmised, had scooped the hole with his trunk, probably tossing the dirt on himself. Noting the hints of stale urine in the air and a pile of partially dried dung off to side of the road, he estimated, “It could be last evening.” The development seemed promising, but the guard on duty told us we were out of luck. Mutware had already moved on.

We decided to try another guard station, on the other side of the lake. Arriving a few minutes later, we were maneuvering the boat ashore when a man on land started hurriedly motioning for us to turn around. He said he’d seen Mutware on a hill back across the lake that morning, about two hours earlier. Reversing course and continuing our zigzag search, I asked Mutangana a nagging question: “What are we supposed to do if we actually track down Mutware and he’s not happy about it?”

Run, he advised. “But you don’t go straight,” he said, adding that we should head, quite literally, for the hills. “It never goes up.”

“What about climbing a tree?”

“A tree?” he laughed. “A tree is nothing.” Mutware is known for much larger conquests, especially during the mating season, when his frustration over his inability to find a female often manifests in destructive outbursts. In 2011 he chased a group of tourists away from their picnic spot. When they returned, their SUV was nowhere to be seen. After much searching, Mutangana noticed tire tracks headed straight for the lake. As it turns out, Mutware had dragged the vehicle more than one hundred feet into the water.

Motoring back across the lake, Mutangana said that the exasperated park staff finally got fed up with Mutware a few years back. “We wrote a letter to [President Kagame],” he said. “We wanted to do away with it.” Even that, though, would have taken a special game rifle. Mutangana has lost count of how many normal bullets are lodged inside the elephant. “It would fall down, but it gets up,” he said, explaining that AK-47s do very little against Mutware’s tough skin and bony skull. Kagame, however, didn’t authorize the request for a bigger gun.

Approaching the shore, I quizzed Mutangana, occasionally glancing up at the bushy hillside growing in front of us. “How old is Mutware?” I asked.

“Roughly around forty-five,” he obliged.

“Is Mutware healthy?”

“Apart of the tusks, it’s good,” then a pause. “It’s coming this way!” he shouted, aiming a finger toward a mass of trees and shrubs. “You can see.” I couldn’t. Mutware’s brown frame blended seamlessly in with the ambach and umuvumu trees. Mutangana suggested proceeding on foot.

“You mean walking toward him?” I asked, skeptically. He answered by radioing for backup. Two rangers came out to guide us to shore, rifles in hand. Mutangana assured me they were there to protect us against buffalo, not to shoot the elephant—a minor comfort.

Moving over, under, and around a jumble of Imihokoro vines, we made our way off the shoreline, hoping to put some distance between Mutware and ourselves. After we reached a grassy clearing, safely out of the elephant’s path, we turned back toward the water. Peering through the trees, I could see the hump of Mutware’s spine, barely visibly under a shower of leaves. As far as I could tell, he was picking them up and tossing them over his back, though at least some must have ended up in his mouth. Presumably the point of all the foraging.

Juan, the photographer, snapped a few pictures of the veiled elephant, before we cautiously made our way back to the boat for a better view. “Let’s first wait and see what he’s intending to do,” whispered Mutangana, who had stayed on the water, his eyes fixed on the brown rump still rustling around in the trees. “Any luck, he could be coming to water.”

A few moments later, Mutangana started pointing again, as the lumbering mass loped through the papyrus and grass, down to the water. Juan’s camera started clicking furiously through a light rain that had begun to fall. Mutangana and I stared at Mutware. Then he saw us.

As Mutware charged through the last layer of brush, I caught a brief glimpse of the off-white nubs where his tusks used to be, and then he plunged headlong into the water. Three hundred feet of separation was rapidly disappearing, when, just as suddenly, he came to a halt. “It’s lying down,” said Mutangana, as perplexed as we were. Mutware shoved trunks full of muddy papyrus root into his mouth.

For fifteen minutes, maybe longer, we watched as the romping and stomping continued along the lakeshore, in no particular direction at all. Rolling in the muck, he looked happy to me—or at least content—despite Mutangana’s insistence that we not read too much into the elephant’s emotions. “It’s like forgetting the life it used to live before,” remarked Mutangana. As we made our way back to the pêcherie, the elephant’s massive gray form receded into the horizon, indifferent to our departure. “It has some kind of peace.“

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.