For the October issue of Harper’s Magazine, Rachel Nolan traveled to El Salvador, the only country in the world that systematically finds and punishes women suspected of having abortions. In January, after the number of registered Zika cases there climbed over 4,000, the Health Ministry recommended that women avoid pregnancy for two years. As she writes in her piece, “Innocents,” this response seemed particularly absurd for El Salvador, a country of 6.3 million where at least five women are raped a day, gangs use rape as an initiation rite, and a third of those pregnant are under the age of nineteen. To stop Zika from spreading, health officials have also been going out on eradication rounds. One day this spring, Nolan tagged along.

In El Salvador, people are less afraid of Zika than of what everyone seems to call “the situation.” As in, we can’t go there because of “the situation.” Doubling down on euphemism, “the situation” is “complicated” in that part of town. “Complicated” means that gangs are busy killing each other there—you’d better take the long way around.

When I joined a group of Health Ministry officers on their eradication rounds in San Salvador, the capital, we were assigned to the neighborhood of Colonia Iberia, where, they explained, the situation was certainly complicated. The crew seemed nervous, and not at all happy to have me with them. “It’s a community,” a health officer said, and another translated that this meant that gang members prowl openly. If you call the police, they won’t come—they might not be allowed in. That day, the “community leaders” (the gang hierarchy), had given us permission to enter.

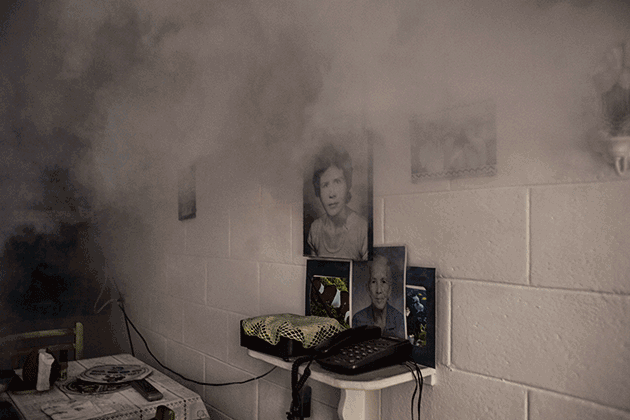

Sanitation workers fumigate houses, streets, sewers, and schools to kill mosquitoes, San Salvador. Photographs © Nadia Shira Cohen

It was nice of them to be concerned about Zika. José Antonio Leiva, a sixty-something, ruddy-faced entomologist wearing a “Safe T First” baseball cap, told me that gang members usually cooperate with fumigations. “We work directly with them,” he said. In some parts of the country, however, there had been trouble. “They let you enter if they aren’t drunk,” Leiva explained. “If they are drunk or high they assault you. Sometimes they say you better leave now, because if not we are going to kill you.” If the palabrero (the gang spokesman) says health officers can’t come in, they don’t. The day before, I’d learned of a health worker who had been warned not to go into Ciudad del Gabo, territory of a gang that was warring with the one in charge where he lived. He went anyway, and once he arrived, he was separated from his group and shot. Two other health workers, a couple, had been shot in their home by one gang for providing services in an area run by another gang. Traitors.

Our Health Ministry truck turned down one of those roads that your stomach tells you not to follow. We parked at the bottom of a hill and off-loaded pink canisters containing packets of a sharp-smelling larvicide called Abate. For the past four years, the country has endured a serious drought, and most Salvadorans store extra water in their houses, which incubates mosquito larvae. In April, Zika eradication became even more difficult when government officials declared a water-shortage emergency. By the time I arrived, two weeks later, many parts of San Salvador had gone two or three days without water, and in the poorest areas, taps were running dry for as long as two weeks. Aedes aegypti mosquitoes were multiplying.

The crew walked up Colonia Iberia’s main street, past a few stores and outdoor grill joints. The place was all right angles, with concrete and dirt alleys, and row houses with their grate doors closed. We were to work the alleys in a zigzag pattern from the grill at the top of the road to the houses at the bottom, handing out Abate packets. (The government is also distributing baby fish, alevines, that are known to eat mosquito larvae in standing water, but my group didn’t have those—Abate kills the fish.)

I set off with Gerardo Criollo, a shy young health official with wire-framed transition lenses. He knocked on each door and called out, “Good morning, sir, Ministry of Health. May we enter?” It occurred to me that this effort was a strange combination of thoroughness and lunacy. Even if the Health Ministry eradicated all the Zika in this area, wouldn’t it just return from the gang neighborhood next door, where we weren’t allowed to go?

The first house belonged to an old couple. The wife, in a blue-and-white lace apron with coiffed white hair, led us to the back and showed us to the pila, a large sink filled with water. Criollo took a mini flashlight out of his pocket, and shined it into the pila. The water moved—it was full of larvae. The woman was mildly embarrassed, saying it had been fifteen days since someone last brought Abate. She hadn’t cleaned the pila since then.

The first house belonged to an old couple. The wife, in a blue-and-white lace apron with coiffed white hair, led us to the back and showed us to the pila, a large sink filled with water. Criollo took a mini flashlight out of his pocket, and shined it into the pila. The water moved—it was full of larvae. The woman was mildly embarrassed, saying it had been fifteen days since someone last brought Abate. She hadn’t cleaned the pila since then.

“It would be best if you threw out the water,” Criollo said. “It has larvae.”

“Throw it out, then,” the woman answered.

Neither of them pulled the plug to empty the water. Both knew that if they did, she might not be able to refill the pila for days, and then she and her husband wouldn’t be able to bathe. Criollo threw a packet of Abate into the pila and said he would be back. “Thanks for your visit,” the woman said.

As we left, Criollo pointed out that all the houses had a little hole in front, through which water flowed from the pila inside to the street. The alleyways collected fetid water. “This worries me,” he said, “but if I ask, they are going to tell me it isn’t their problem.”

Most people let us into their homes. The Health Ministry had gone through the same routine for dengue decades ago and for chikungunya, in 2014. The first person to refuse us entry was a teenage boy, who said only, “We are busy cleaning.”

About half an hour into our rounds, we heard reggaeton coming from one of the grills, where the gang guys were starting to gather. They wore sports jerseys and flat-billed caps, and ate a late breakfast of pupusas in a bath of red sauce. One guy was smoking a big joint. There were no visible guns. They ignored the health workers. Passing them on the street, I said “permiso,” and they politely answered, “pase.”

One of the last houses we visited was full of women. A bored teenager sat on the couch watching a Mexican soap opera. The pila was clean, with an old packet of Abate floating inside. Criollo threw in a new one. Two women stood chatting at the back door; one wore a T-shirt printed with a green apple, and the second, in a blue tank top and red shorts, was hugely pregnant. Green Apple was saying, “I couldn’t swallow my breakfast, it got stuck here.” She pointed to her throat. “I told them to deliver the message right. But now they are going to kill me.” Evidently, someone had screwed up.

One of the last houses we visited was full of women. A bored teenager sat on the couch watching a Mexican soap opera. The pila was clean, with an old packet of Abate floating inside. Criollo threw in a new one. Two women stood chatting at the back door; one wore a T-shirt printed with a green apple, and the second, in a blue tank top and red shorts, was hugely pregnant. Green Apple was saying, “I couldn’t swallow my breakfast, it got stuck here.” She pointed to her throat. “I told them to deliver the message right. But now they are going to kill me.” Evidently, someone had screwed up.

The pregnant woman stepped away from her friend to greet us. Some of her neighbors had been diagnosed with Zika. “And thank God, He saved me from that,” she told me. “Thank God I didn’t get it. Now the moment has passed, because it affects the baby most in the first three months. Everything looked good on the ultrasound. I imagine that there they would have told me.” Her friend Green Apple had come down with Zika and chikungunya, she said, but now she was doing just fine—except for the fact that she was likely about to be murdered. I was reminded of what a feminist activist told me about Zika, compared to all the other dangers women face in El Salvador: “It’s not a matter of concern.”

Read Rachel Nolan’s story for the October issue here.