Fun, in Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, is a calendar event. Out here, on the largest and most remote oil field in the United States, thousands of workers rise each morning in endless summer, eternal darkness, mosquitos, and snow, to begin twelve-hour shifts, which on the drilling rigs requires a discipline that is taken seriously: a mistake, however small, could cause this entire place to explode, as it did in West Texas two years ago, or in Texas City twelve years ago. For a change of landscape one can board a bus with elderly tourists to the edge of the Arctic Ocean, point out the artificial palm tree, suggest a dip, and laugh—the water is 28 degrees—but even that route grows dull: the single gravel lane that traces tundra abuts miles of pipeline. For the oil workers, there is little to look forward to before the end of a two-week shift except for scheduled socialization. Each summer, such fun goes by the name Deadhorse Dash, a 5K race traced across nearby Holly Lake.

“Last year, someone dressed up as a dancing polar bear,” Casey Pfeifer, a cafeteria attendant, tells me when I arrive at the Prudhoe Bay Hotel for lunch on the afternoon of the race. Casey is wearing purple eyeliner and a sweatshirt that reads MICHIGAN in looping gold-glitter cursive. Every two months Casey travels between Idaho and Prudhoe Bay—for her, life in Alaska is synonymous with adventure—to work in the service industry at places like the Hotel, which is not actually a hotel at all but a work-camp lodge, with hundreds of tiny rooms housing twin-size cots and lockers. Casey smiles at me from behind her warming tray and I feel cozy, despite the dirt and dust clinging to my skin. The fluorescent lights illuminate her golden hair, which is tucked into a sock bun, and she tongs a sliver of battered cod. “Picture it,” Casey says. She sways her butt to the sound of nothing. “This giant bear, and he is grooving.”

I picture an enormous mascot gyrating to the Backstreet Boys. It is not my idea of fun, but I am an outsider. I had arrived on the North Slope only the day before, seeking a week in the most isolated community in America and what I hoped would be storybook Alaska: purple arching Coho salmon, caribou, moose, air that belongs in a breath-mint commercial. Instead I found square buildings like so many others, and a cafeteria just like that of a high school, with wheels of cheesecake and racks of chips. How normal everything felt. At an empty table, I watch workers lay playing cards out in front of them. Behind them, mounted televisions loop the Steve Harvey Show and Maury, The Price Is Right and Dr. Phil. Workers in heavy coveralls spoon cubes of honeydew onto their plates, consider the merits of the cacciatore, and pile their bowls with limp linguini. They puff their cheeks like chipmunks, gearing up, they joke, for what would no doubt prove a feat of monumental athleticism.

“The calories aren’t expended in the walking,” one worker tells me, reaching into a basket of Little Debbie Swiss Cake Rolls. I watch as his hands, the largest I have ever seen, raise the cakes to his mouth. He consumes them whole, parting his lips dramatically—wet pink petals, upon which the skin blisters, burned by Arctic sunlight. His name, he says, is Jeff Snow, but he goes by Snowman. He earned the nickname in the dead of winter, because up here, he comes alive: a redneck, forklift-driving Frosty the Snowman, made animate by extremes.

“The real work tonight is swatting the mosquitos,” Snowman says. He rolls his eyes, he laughs.

“The Deadhorse Dash is mostly bullshit. But it’s the sort of bullshit you look forward to.”

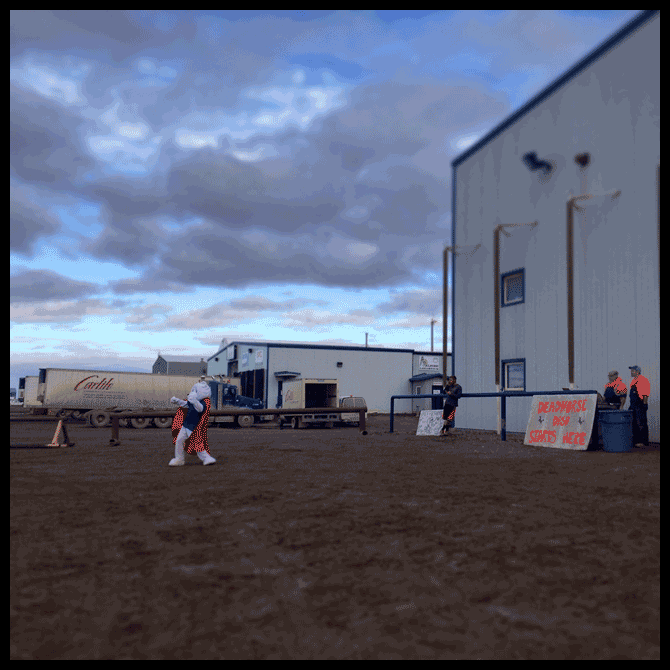

According to posters fixed to the cafeteria’s white-painted cinderblock walls, participants are to meet at six o’clock by the biggest warehouse in the stretch, owned by Carlisle Transport. The evening would start with a few minutes of mingling, during which men with binoculars would scan the horizon for polar bears. “They rarely come in this far in summer,” Snowman says, “but better alive than dead and sorry.” Once our safety is assured, we would set out across the tundra, tracing a two-mile stretch from one edge of Holly Lake to another across a landscape normally restricted to oil-field employees and suppliers who hold the highest level of security clearance. At the halfway checkpoint, marked by a folding table, we would collect a token, redeemable at the finish line for a burger, a handful of chips, a chocolate-chip cookie wrapped in thin plastic, and our choice of apple or banana.

An Arctic picnic in eternal summer.

“It’s a privilege, really,” Casey says. There is a home-away-from-home feeling here, she explains. But still, one passes most days as if a zombie. You rise, you work, you eat, you go to bed, repeat. Mostly, life on the North Slope is spent waiting to return to life in the Lower 48 and, with it, a return to children’s birthday parties, dinners with the spouse, backyard barbecues, and the simplicities of normal life: a fishing line, unfurled and bobbing red above a riverbank in Idaho.

“Put it to you this way,” Snowman says. “We don’t do anything up here but work and sleep and eat. So shit like this means an awful lot.”

Casey nods. She heaps fish onto another worker’s plate and hands him a wedge of lemon.

“We’re only allowed out on the fields for scheduled events,” she says, “because everything beneath is oil. . . . Someone lights a match and we all go boom.”

But on this night, there would only be food and fun and walking. If we are lucky, I am told, we will see roaming caribou, perhaps a herd of musk ox—or evidence of their passage the previous night in tufts of fur collected by the Arctic grasses.

If there are no wild animals in sight, we can count on the mascot and his erotic gyration.

“It’s not the same,” Casey says, “but it helps. You know. The hips.”

She tells me about her nieces and nephews who have learned to sew socks from the baggies of musk-ox fur she mails home every month. The fabric is bristled but unexpectedly soft.

“It’s the little things,” she says.

Around me, men and some women watch the television screens with tired eyes. I spoon some macaroni—some of the best I’ve ever had—into my mouth as Vanna White, shimmering in sequined silver, turns a square over to reveal an R.

“I’ll tell you what.” Casey emerges from the snaking buffet line, her smell like baby powder, to put a hand on my shoulder and look knowingly at my feet. I am wearing Xtratufs, industrial rubber work boots, which I had ordered online and shipped to my home in full-on Midwestern summer. They were chosen after careful research in an attempt at authenticity, but their glossy surface, unmarred by rain, negative temperatures, or any evidence of wilderness, revealed my inexperience. I scuff them against the blue carpet and ground-down remnants of Doritos.

“You should join me tonight,” says Casey. “You look—a little out of place.”

I knew the sun would not set tonight, or tomorrow, or for the next two months, and because I had yet to see a musk ox, and had never stepped out across thawing tundra, I tell her yes, I’d love that. Casey nods again, and we make plans to meet at six, at the big puddle in front of the hotel’s generator.

When locals speak of Alaskan geography, they often hold out their right hand as if in preparation for an upside-down handshake. Fingers folded at the knuckle, palm flat, index pointer veering left and thumb turned downward at a right angle.

Here, they say, pointing to a knuckle. This is Denali peak.

Or they point to the joint that connects the index finger to the palm—Anchorage, say, or Valdez. The tips of fingers are the coastlines: King Salmon, Bethel, Nome. More rarely, someone will point to the top of the hand, the shallow divot where the pinky finger dips inward as it meets the underside of the palm. This is Prudhoe Bay.

Perhaps more than any other community in America, it is place where camaraderie is born of necessity: you are here and make the most of it. At six o’clock, I show up at the muddy edges of the big puddle to find Casey changed from her industrial apron to a blue velour tracksuit that reads DRAMA across the butt.

“I call it,” she says, “Arctic chic.”

We walk to the starting line of the Deadhorse Dash, where several dozen people were packed together in casualwear, brown leather boots, and mosquito netting. Casey notices the industrial-size can of bear spray that I am clutching, and laughs.

“The time it takes to spray it,” she says, “is all the time it takes to die.” Bears run, she explains, as fast as a horse, nearly nineteen miles an hour.

“Still,” I say, shrugging, as my fingers tighten around the can.

Earlier, it had rained, which happens more often than not in the short summer season, but already the ground had sucked the water back and drained the shallower puddles dry. Casey points to a patch of tundra from which a cluster of pink azaleas was growing.

“This place,” she says, as if it were a postcard. She kneels and parts the petals, shows me the way the roots intertwine, how lichens cling to shallow rock in an otherwise empty stretch of shallow soil. “Everything,” she says, “must stick together. Men and women, flora and fauna.”

The men and women around me are all laughing. They lean into one another, heavy hands on heavy shoulders. We are waiting for a cue, some indication that everything is in its proper place: the token-givers, the Styrofoam plates, the hamburgers, the polar bears. When the bullhorn finally sounds, we lumber forward onto the oil field, half a dozen of us in sweatbands, the rest advancing gradually with the knowledge that there are plenty of cookies.

Casey pulls two netted hoods from her pocket.

“Thanks,” I say, swatting a mosquito just in time to burst a bubble of blood along my hairline. The insects invade my ear canal, their noise high-pitched and urgent.

Although it is the height of summer, already the ten-day forecast is calling for snow, and two months from now, Casey tells me, everything I see will likely be lost to ice. She swivels her velour hips and points to a work camp at the very edge of the oil fields.

“See the stilts?” she asks.

In temperatures that dip to a frigid and nearly unlivable negative sixty, the tundra is in a constant state of redefinition, even if firm to the touch. “Like that Oobleck stuff you make in elementary school,” Casey says.

Every newly constructed building must be set upon concrete stilts, or else the heated air inside will thaw out the exterior, creating a bog that will suck the whole building into the earth.

Somehow, we have reached the halfway mark.

“Thank you,” Casey says, as we collect our token from a man so red-cheeked and round I cannot help but think: Santa Claus?

“He gets that a lot,” Casey concedes. “Sometimes I think it’s intentional.”

We turn to make our way back, and from this vantage point, two miles out, the landscape seems suddenly and intimately foreign—a moon, an alien planet, colored warehouses flanking the visible horizon like enormous Lego cubes. I feel, for one fleeting second, what some workers called “the crush of isolation”—the realization that you are so very far away from everything, despite the carousels of condiments, the freezers of popsicles, the Gushers and the Fruit Roll-Ups and this insistence on familiar Americana.

Finally there comes the music, the smell of grilled processed meats, and the polar bear, who gestures me forward with one fuzzy paw. I leave Casey behind and we bend at the waist for Shaggy’s “Angel,” rolling our arms like fleshy noodles. He takes my hand in his and we dance, the ground giving slightly to each step.

All around us, the workers of the North Slope queue up photos on four-inch screens. They pass them around with oral captions: last Sunday’s baptism, pool party, we celebrate twenty-two years on Friday. One man points to a pair of tiny cheeks smeared with fluorescent green frosting—his youngest son Emerson’s first birthday.

“It would’ve been great,” he tells me. “Just wasn’t in the cards this year.”

He asks me if I remember my first birthday, if I had chocolate sheet cake or vanilla, if I can recall who was or was not there. I shake my head and say that no one could possibly remember.

His eyes soften with relief. “Yeah,” he says. “I’ll catch his second lap around.”

Then he—and everyone—mouth the words to “Ice, Ice, Baby.”

Fifteen hours south, in the rest of America, people wait for our return, but until then, we clap our hands, swivel, and dip. Casey inspects the ground for fur. All around us hum the engines of planes, helicopters, enormous motors that lift up into the air over the blank horizon, freighting workers back to milder places.

From the barren tundra, we watch one rise.

And, just like that, it is gone.