Inside the June Issue

Michael Glennon on Trump's war with the security state, Helen Ouyang on health care in the Black Belt, Rebecca Elliott and Elizabeth Rush on the battle over New York City’s flood zones, a story by Nell Zink, and more...

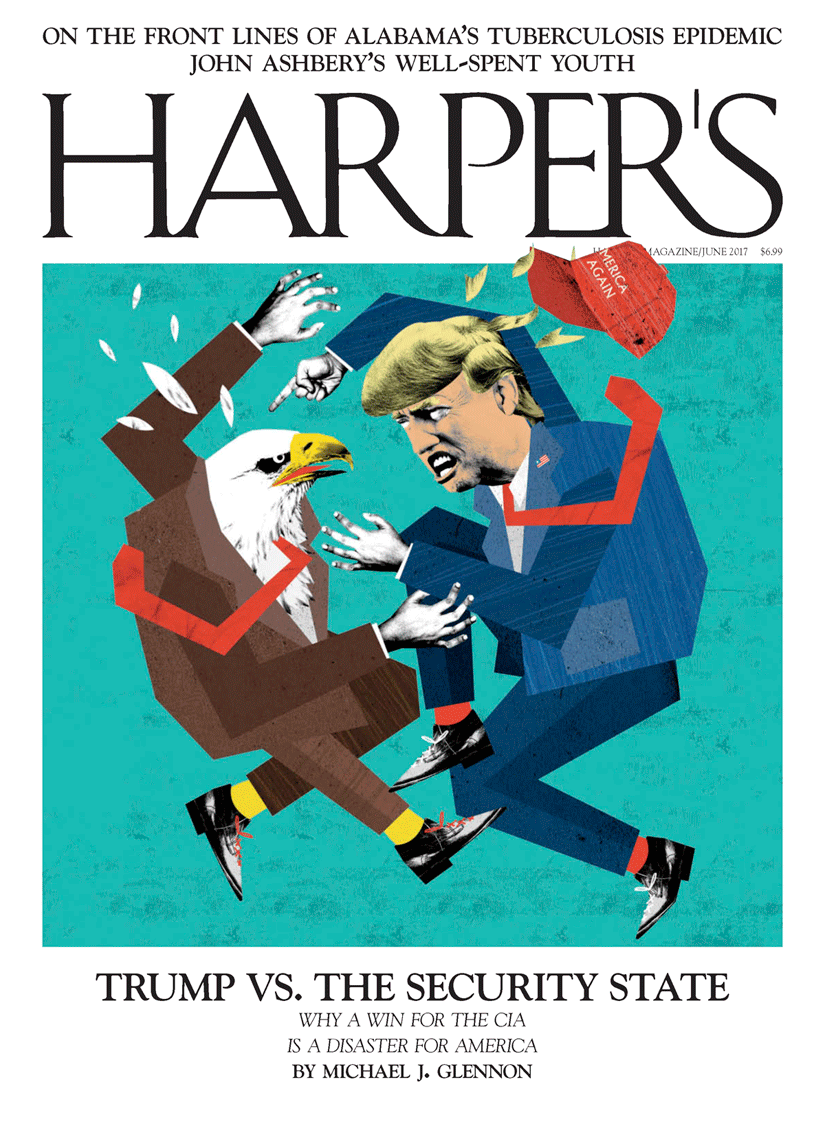

During the recent presidential campaign, Donald Trump regularly described America’s intelligence agencies as fumblers—unless they were snapping at Hillary Clinton’s ankles, in which case they were ardent patriots. (The G.O.P. candidate told a frothing crowd in New Hampshire that he was “actually, really, very proud” of the FBI for reopening its investigation of Clinton’s emails just days before the election.) Relations between the security bureaucracy and Trump have only worsened since then—culminating, most recently, in the firing of FBI director James Comey. Many liberals have hoped that the CIA, FBI, and NSA, all of them in the presidential doghouse, would push back against the Trump’s worst excesses. But in “Security Breach,” Michael J. Glennon warns against viewing the security state as a heroic firewall. These agencies were not created to keep the other branches of government in check, despite their mad metastasizing during the postwar decades. They were never intended, in Glennon’s words, “to be a coequal of Congress, the courts, and the president.” Nor do they have unspotted records when it comes to the preservation of civil liberties (to say the least). We may delight in their guerrilla war against Trump, fought with leaked intelligence and heat-seeking inquiries, but once we have licensed them as the last best hope of democracy—well, be careful of what you wish for.

During the recent presidential campaign, Donald Trump regularly described America’s intelligence agencies as fumblers—unless they were snapping at Hillary Clinton’s ankles, in which case they were ardent patriots. (The G.O.P. candidate told a frothing crowd in New Hampshire that he was “actually, really, very proud” of the FBI for reopening its investigation of Clinton’s emails just days before the election.) Relations between the security bureaucracy and Trump have only worsened since then—culminating, most recently, in the firing of FBI director James Comey. Many liberals have hoped that the CIA, FBI, and NSA, all of them in the presidential doghouse, would push back against the Trump’s worst excesses. But in “Security Breach,” Michael J. Glennon warns against viewing the security state as a heroic firewall. These agencies were not created to keep the other branches of government in check, despite their mad metastasizing during the postwar decades. They were never intended, in Glennon’s words, “to be a coequal of Congress, the courts, and the president.” Nor do they have unspotted records when it comes to the preservation of civil liberties (to say the least). We may delight in their guerrilla war against Trump, fought with leaked intelligence and heat-seeking inquiries, but once we have licensed them as the last best hope of democracy—well, be careful of what you wish for.

In “Where Health Care Won’t Go,” Helen Ouyang chronicles an outbreak of tuberculosis in Marion, Alabama. This small town is located in the so-called Black Belt—a ribbon of rural counties with a long history of racism and poverty—and not surprisingly, health care is in short supply. Once the first case was discovered, state authorities intervened, but the epidemic has yet to be contained. “It’s not looking good,” the state’s tuberculosis controller said. Ouyang’s story points to a deeper, ongoing crisis in this country: Americans living outside of urban areas frequently have few health-care options or none at all, which is exactly what sets the stage for a mini-epidemic like Marion’s. What we are left with is a vicious cycle of illness and economic impoverishment. “We’re not progressing at the same rate as everybody else around us,” a local physician wistfully told the author. “We’re just kind of stuck.”

Not that city dwellers everywhere have it all that easy. In “Stormy Waters,” Rebecca Elliott and Elizabeth Rush explore the battle over New York City’s flood zones—those portions of the Big Apple that are likely to be inundated during the next apocalyptic hurricane. The precise delineation of these zones has led to a cartographic tug-of-war between FEMA, whose predictions are suitably dire, and real-estate developers, who would have to shell out enormous sums to make their buildings flood-resistant. Meanwhile, Daniel Brook looks at a post-apocalyptic metropolis in “Here A City Shall Be Wrought.” His subject is Beichuan, China, which was destroyed by a 7.9-magnitude earthquake in 2008, then quickly reconstructed in a new location fourteen miles away. The spanking-new Beichuan is, in Brook’s words, an experiment in “time-lapse urbanism,” which he finds both “enviable and cloying.” More disturbing is the ruin of the old city, which has been left intact as a memento mori and symbol (at least in the eyes of party officials) of Communist solidarity.

Elsewhere in the magazine, Gary Greenberg ponders the mathematics of predicting war, and Julia Harte asks: “When can the legal system hold accountable those who occupy the highest offices in the land?” In Readings, we have interviews with Syrian refugees, a thousand-year-old poem by Abu al-Hasan ‘Ali bin Hisn, a parliamentary debate over rhododendrons, and a list of memorable names that parents have recently tried to bestow on their children, including “Tiny Hooker,” “Cholera,” “Ghoul Nipple,” and the relatively innocuous “Satan.” Last but not least, there is Matthew Bevis on John Ashbery, Christine Smallwood on New Books, and a hilariously vicious fiction by Nell Zink, her first story for the magazine.