Inside the July Issue

Zadie Smith, Masha Gessen, Rebecca Solnit, Joseph O'Neill, and more...

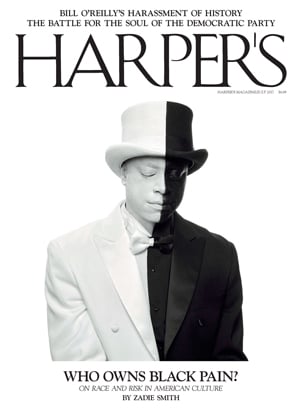

“We have been warned not to get under one another’s skin, to keep our distance,” Zadie Smith writes in this month’s cover essay. Her nominal topic is appropriation—the borrowing of cultural goods that is either cross-pollination or pure plunder, depending on your point of view. At first, in her consideration of the Jordan Peele film Get Out and the Dana Schutz painting Open Casket, Smith seems to regard such behavior as little more than psychic cannibalism. White Americans want to get inside the black experience—without, of course, coping with police violence, redlining, or what is by now bred-in-the-bone bigotry. Yet Smith’s ultimate conclusion is far more complicated. The antagonism between races (a misnomer to begin with) is inseparable from a tragically warped intimacy. To be oppressed, she writes, “is not so much to be hated as obscenely loved. Disgust and passion are intertwined. Our antipathies are simultaneously a record of our desires, our sublimated wishes, our deepest envies.” She then goes further, wondering whether her own biracial children are the rightful heirs of black culture and black pain—and whether any such system of color-coded inheritance makes sense in the first place.

“We have been warned not to get under one another’s skin, to keep our distance,” Zadie Smith writes in this month’s cover essay. Her nominal topic is appropriation—the borrowing of cultural goods that is either cross-pollination or pure plunder, depending on your point of view. At first, in her consideration of the Jordan Peele film Get Out and the Dana Schutz painting Open Casket, Smith seems to regard such behavior as little more than psychic cannibalism. White Americans want to get inside the black experience—without, of course, coping with police violence, redlining, or what is by now bred-in-the-bone bigotry. Yet Smith’s ultimate conclusion is far more complicated. The antagonism between races (a misnomer to begin with) is inseparable from a tragically warped intimacy. To be oppressed, she writes, “is not so much to be hated as obscenely loved. Disgust and passion are intertwined. Our antipathies are simultaneously a record of our desires, our sublimated wishes, our deepest envies.” She then goes further, wondering whether her own biracial children are the rightful heirs of black culture and black pain—and whether any such system of color-coded inheritance makes sense in the first place.

In “The Reichstag Fire Next Time,” Masha Gessen looks back at the dismal history of political crackdowns. Many of these, she recounts, have been preceded by specific catalyzing events—the most famous being the Reichstag fire of 1933, which gave the Nazi Party a green light to destroy its opponents. (“There is no mercy now,” Adolf Hitler declared at the time. “Anyone standing in our way will be cut down.”) Are we on the verge of such an autocratic spiral in this country? If so, what sort of event would precipitate it? The obvious answer is a large-scale terrorist attack on American soil. In Gessen’s view, however, our panicked anticipation of such a disaster is distracting us from what is going on right before our eyes. “That we seem so certain of the outlines of the Reichstag fire to come,” she writes, “reveals the fact that it has already occurred.” A crackdown, she argues, is sometimes a slow-drip affair, and the death of a civil society may well be accomplished by a thousand legislative and regulatory cuts.

In his latest Letter from Washington, Andrew Cockburn describes the efforts of the punch-drunk Democratic Party to reconstitute itself—or at least get up off the canvas and prepare for the next round. As always, there is the fundamental friction between the Washington-based bureaucracy and the grassroots activists in the deep-red hinterlands of Kansas, Nebraska, or Georgia (where Jon Ossoff may yet sail to victory in the state’s Sixth Congressional District). Garret Keizer revisits the great Paterson Silk Strike of 1913 in “Labor’s Schoolhouse,” and ponders what lessons might be derived from that exemplary show of solidarity and subsequent defeat. “Ghost Nation” is a scrupulously reported account of the slow-motion holocaust unfolding in South Sudan—where, as Nick Turse notes, the Trump Administration “seems unwilling to offer even an honest assessment of the carnage, much less take any action.” And in “The Weekly Package,” Kim Wall describes how Cubans, deprived by their own government of internet access and the resulting cornucopia of pop-culture delights, have found the most cunning of analog solutions. (Hint: it gets delivered in a crimson velvet pouch.)

It was Bill O’Reilly’s sexual conduct that finally got him ejected from the Fox News mother ship. But we should be no less alarmed, writes Matthew Stevenson, by O’Reilly’s role as America’s favorite historian, whose most recent book, Killing the Rising Sun, sold more than a million copies last year. As Stevenson demonstrates, this account of the Pacific War is a tissue of errors, distortions, and heavy-breathing jingoism, culminating in a fact-free pep rally for nuclear weapons (which incinerated Hiroshima’s red-light district while mostly leaving intact the nearby munitions plant and shipyard).

Elsewhere in the magazine, we have “The Mustache In 2010,” a wonderfully idiosyncratic story by Joseph O’Neill, and a look at Lenin’s afterlives by Sheila Fitzpatrick. In Readings, Ellen Ullman demystifies the world of programming and decries its deeply male bias, which tilts the terrain toward boyish nerds and clueless mansplainers. There is also Marcel Proust complaining about his noisy neighbors from the sanctity of his cork-lined cloister, Oli Hazzard’s “Early Modern Love Poem,” and an advisory from the Russian Foreign Ministry. When in Uzbekistan, the traveler is told, “do not abuse or insult your listener’s mother.”