Pivot to Digital

Tom Tryniski isn’t trained as an archivist. Nor does he have ties to any institution or receive much compensation for the many hours he’s spent scanning the microform of local newspapers he orders from libraries. Still, he is devoted to the endeavor. Since his retirement in 1999, he has digitized some forty million newspaper pages and posted them to his website, fultonhistory.com. His collection, at three times the size of the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America archive, is in all likelihood the largest free repository of its kind.

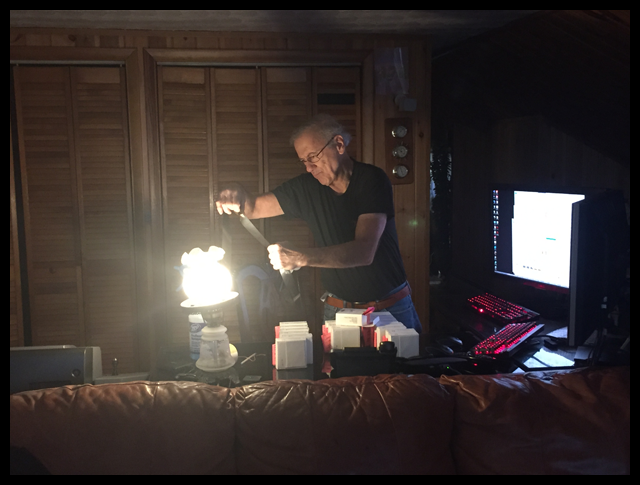

But there is more work to be done, Tryniski says. “Do you have any idea how many rolls of microfilm the state of New York has?” the sixty-eight-year-old asked on a Wednesday afternoon in November, his face illuminated by two massive computer screens. He was sitting in his living room in Fulton, New York, a declining industrial town twenty-three miles north of Syracuse. “I’m going to guess 50 million.”

And that’s only counting New York. Tryniski’s archival ambitions well exceed the borders of the state where he has lived his entire life. Fultonhistory.com already contains more than a thousand newspaper titles from across the United States and Canada. But Tryniski knows that his efforts thus far have barely scratched the surface of our vast printed history. U.S. libraries alone contain more than 154,000 U.S. newspaper titles, according to a directory maintained by the Library of Congress. So Tryniski spent that afternoon, the day after Donald Trump was elected president, doing what he has done every day for the past eighteen years: sitting in his living room, tending to his website.

Tryniski is a slight man with a thin covering of white hair. His life is dictated by strict routine, including his daily uniform of T-shirts, blue jeans, and old sneakers. He built much of his house himself. Like his website, the design of which he has not changed since 1999, the building suggests an outsider architect. Disassembled computer motherboards lie in piles under low, sloping ceilings. A gazebo he built on the porch houses an eighty-terabyte server. It’s almost full.

Tryniski, who lives alone, had Fox News on. “It was . . . that working-class voter in those Rust Belt states who delivered the election to Donald Trump,” a commentator said, her face filling the TV screen. “I believe it,” Tryniski replied. He likes Fox News. “I believe it’s fair and balanced,” he said. He can’t say the same about newspapers—neither today’s nor the old ones that he has worked feverishly for nearly two decades to preserve. “You go back to the newspapers from around 1800, of course they were biased!” he said, citing Horace Greeley, the nineteenth-century newspaper editor who promoted Whig and then Republican politics in the New-York Tribune. “Reading the newspaper is simply going to tell you which way it’s tilted,” Tryniski said. The room heaved and buzzed around him. It was the sound of eleven computer processors churning an endless stream of historical newsprint into digital replicas.

Tryniski is both devoted to newspapers and suspicious of them—one of many contradictions in his relationship with journalism. Another is his support of Trump, who regularly heaps scorn on news outlets and has threatened to roll back libel laws to make it easier to sue them. But Tryniski doesn’t take these threats seriously. “He will never attempt it, to silence the press,” he said. “Even though he’s a partial nutcase.”

A shipment of microfilm was waiting for Tryniski at the Fulton Public Library, so he got into his pickup truck and drove across town, past rows of wood-frame houses, then fast-food restaurants and empty parking lots. “Fulton has a lot of history in it,” he said. It was the town’s past that sparked Tryniski’s interest in old newspapers, he said. He liked reading about its bygone paper mills and manufacturing plants. “You could get a job anywhere in Fulton,” he said. And now? “Just the opposite.”

Tryniski parked in front of the library and came out a minute later with a box over his shoulder. Back home, he sliced into it with a screwdriver, revealing fifty small cardboard cartons labeled Ridgewood Times. He’d ordered them via interlibrary loan after a man who grew up in Ridgewood, Queens, emailed Tryniski asking him to upload the neighborhood paper to his site. Much of the microfilm he now scans lands on his to-do list because of such requests—some even from public libraries. The professional scanning companies are expensive, whereas Tryniski asks only for donations in exchange for his work. Most of the time he does it for free.

Once scanned, the Ridgewood Times would join the Port Chester Journal, the Rochester Daily Record, the Chattanooga Daily Times, the Troy Times, the Stillwater Messenger, the Gloversville Intelligencer, the Peekskill Highland Democrat, the Essex County Republican, the Homer Independent, the Lackawanna Leader, the Dakota Gleaner, the Louisville American Baptist, the Plummer Pioneer, the Ohio Socialist, the Victoria Daily Colonist, the Silver Creek Gazette, the Silver Creek News, the Silver Creek Times, the Silver Creek News and Times, the Creeker (of Silver Creek), the Springwater Enterprise, the Vermontville Echo, the Shakopee Argus, and other newspapers in Tryniski’s archive.

He sat cross-legged on the floor and began arranging the microfilm boxes into chronological rows. “When I was a kid I used to go to the library and run through the microfilm of the Fulton Patriot,” he said, watching the columns of cardboard cubes grow in front of him. “It’s the small-town newspapers that captured everything,” he said. “They reported on all this small-town stuff.” He took ten rolls to his desk and fed the first into a hulking scanner. Grainy newsprint from 1956 flashed across his screen.

Tryniski did not have any experience building archives when he started his website. He learned how to code during his decades working as an engineer at Black Clawson, a company that built paper-manufacturing machines. But what Tryniski lacks in formal training he makes up for in resolve. On average, he works on his website ten hours a day, seven days a week. His average six-month output is 1.6 million newspaper pages.

It is through sheer dedication that Tryniski has built his immense and sophisticated archive. He touches up the digital files when necessary before uploading them, and runs them through word-recognition software, making his entire trove searchable to the letter. The site has become the envy of more established competitors such as findmypast.com and newspapers.com, whose collections themselves already contain hundreds of millions of digitized newsprint pages. Tryniski calls them the “big boys.” He has received buy-out offers in the six figures, but he turned them all down. He doesn’t want his newspapers hidden behind a paywall, he said.

Tryniski’s commitment to the free, communal use of online resources seems at odds with his staunch conservatism, but he doesn’t see it that way. To him, fultonhistory.com exemplifies the virtues of free enterprise. The big boys may be flush with funding and trained archivists, but all their overhead slows them down, he said. Alone with his scanner and his fleet of computers, Tryniski is unfettered.

There are other perks to being your own boss: no need to look professional. Thus some of the weirder features of Tryniski’s site, such as the animated goldfish that swims across the splash page, the occasional live stream of a squirrel eating corn on Tryniski’s porch, and the button labeled “Page Me” that plays an explosion when clicked.

“It’s a sense of humor,” Tryniski said. “Most people get a charge out of it. Some people think it’s crazy. But then again, when they come to my site, they’re on my dime, right? I’m going to put crazy things on my site if I want.”

Tryniski’s website is still only a hobby for him, and not necessarily a permanent one. “I will no doubt move on to something else like I always do,” he said. A microfilm roll finished running through the scanner and spun on its spool, flapping. “Prior to this I was into four-wheeling, Jet Skis, motorcycles. My Corvette is downstairs, I’ve had it for forty-something years,” he said. But “I got sick of it in 1982. I pulled it in the garage, I put a tarp over it. I never looked at that car again until 1989. Then I decided to pull it apart and rebuild the whole damn thing.”

Perched on a router in Tryniski’s living room are framed portraits of his mother and father, both deceased. They are the only photographs on display. Tryniski is unmarried and has no children, but he does not get lonely. “I’m happy doing this,” he said, his scanner next to him humming. “This is my legacy. One hundred years from today, they’re going to say: ‘Yeah I know that Tom Tryniski, he’s the one that digitized all these newspapers.’ Now if I didn’t do something like this, people will say: ‘Who’s Tom Tryniski? Never heard of him.’”

The next morning, Tryniski went to Mimi’s Drive-In, as he does every weekday, to drink coffee and read the local papers. A giant photograph of Trump covered the front page of the Post-Standard from Syracuse. “‘No Dream is Too Big,’” read the headline.

Tryniski used to read the Fulton Patriot too, but it stopped printing in 2010. The remaining papers in the area have struggled to hold on. “Every one of these papers I’ve mentioned has shrunk,” Tryniski said. He held up the Valley News, now the size of a large pamphlet, and laughed. Despite his efforts to conserve local newspapers, Tryniski is unsentimental about their decline. “They’re dying for a reason, because of the internet. That’s just the way it is,” he said. “If they were viable for the city, they’d still be in business.”

The diner was packed. “This is one of the busiest places in town,” he said. A woman hobbled in on a walker strapped with an oxygen tank. Hillary Clinton visited Mimi’s during her 2000 Senate campaign, but Tryniski didn’t go. He voted for Trump in 2016, after previously supporting Obama, like many of his neighbors. In 2008, Obama received 50 percent of votes in Oswego County, where Fulton is located. In 2016, Clinton won less than 36 percent.

Tryniski liked Trump’s pledge to renegotiate trade deals and bring back manufacturing jobs, which are sorely needed in places like Fulton, he said. After his coffee, he got back into his pickup and drove around town in search of the UPS truck. The store was closed, and he had a package of microfilm he’s been trying for days to ship back to a library in western New York. He passed a cluster of massive red brick factories with deep gashes in their facades.

“That was the original building that Nestlé started in,” Tryniski said. It was the Swiss food company’s first U.S. plant; Tryniski grew up a few blocks away from it. “Every time it rained there was the smell of chocolate in the air,” he said. The plant once employed thousands in the town, including Tryniski’s mother, who worked on an assembly line producing chocolate chips. But the company started laying off workers in the 1970s. “We all knew it was going to close sooner or later,” he said. The plant shut down in 2003.

“Do I think Trump will be able to bring back Nestlé? No! Not in a million years,” Tryniski said. Still, the nostalgia underlying Trump’s promise to “make America great again” resonates with him. “I miss the old things, the way they were,” he said, surveying his dying town. “Granted, I knew things were going to have to change. But you always look back and say, ‘Boy you know I remember that. Those were the best years of my life,’” he said. “This is my way to express what I feel, through my website. That’s why I’ve got all these old photos of Fulton, and the old history, and the old newspapers.”

He couldn’t find the UPS truck, so Tryniski returned home to continue scanning microfilm.