Allah Knows

Laundry in the bathtub. This was one of the many things my mother did to help my father save the very little money he made for our family, flipping burgers and frying fries in Mr. King’s Gyros on 71st and Halsted in Chicago. We didn’t have a laundry machine, and $1.25 a load at the Laundromat was too much for laundry for six kids. So every Sunday night, just in time for school, my mom would put on a pair of ragged pajama pants and an old t-shirt, place a small plastic stool in the middle of the bathtub, and separate the clothes by color.

She took special care of my father’s clothes, washing them first and hanging them to dry on their own section of the shower pole. Aside from the pajamas and t-shirts he slept in, my father’s only clothes were a pair of work pants, and a white collared shirt he wore to work each day. He had a hole in every one of his t-shirts from smoking in bed. She leaned forward, with her feet in the water, her forehead sweating, and hand washed every sock, shirt, and sweater that had accumulated over the week. In a household of six children, socks alone would fill the wicker hamper. She had a water bucket on each side; one filled with a cup of laundry detergent and water and the other with water and bleach. She would scoop the solution out of the buckets with her hands and splash it on to each article of clothing. The washed, being soapy shirts would go in front of her and the rinsed ones over her shoulders, behind the stool. Her hands were always red. She only used hot water.

She would knead each article of clothing as if it were to be worn at my citywide science fair or my fifth-grade state-wide speech competition. She kneaded and scrubbed so hard that her fingers would shake and her skin would turn red and peel off. Once, so much skin peeled off, she could only wash her hands with cold water for a week. When I asked why she didn’t wear gloves, she said, “They don’t help me scrub hard enough.” The bleach irritated her eyes. She would occasionally step out for a breath of fresh air. I would sometimes help wring them out, but she always took them from me when I was done and still managed to wring out a waterfall.

Laundry in the bathtub. This was what my mother was doing when she found out about my father’s death. It was 11:00 pm, and all of us kids were asleep except me. I just finished my body paragraph for my American Literature class—the role of magical realism in Like Water for Chocolate,” and I was lying on my bed, thinking, trying to fall asleep.

It had been a good freshman year, I thought. I published my first poem in the school newspaper about the beauty and inner strength of wearing the hijab. I had met Lily and Edna, friends I will probably never forget. But it was still a little hard to adjust, being one of only two Muslims wearing hijab in a Chicago Public high school of 3,900—my sister Remal just joined Curie High School as a freshman.

My thoughts were interrupted. Someone rang the doorbell.

My mother was still scrubbing and kneading in the center of the tub. We all ignored it, thinking it was a mistake. It must be for the neighbors, because no one visits us at this hour. The doorbell rang continuously. My mother stepped out of the tub, dried her scratched, burned hands, and walked to the window. “Call your dad,” she shouted. “Tell him it’s the police. Ask him if it’s ok to open the door for them,” she shouts nervously to me. Remal and I both got out of bed. I called my dad’s work phone. No answer. I called again. No answer. “Maybe he’s on his way,” said Remal. I let my mother know that he wasn’t answering. My mother quickly grabbed her prayer clothes—a white, long wavy cotton headdress that extended over her arms—and threw it on her head on her way downstairs. Remal hurried after her as I stayed upstairs, still trying to call my father.

Two police officers, a male and a female, were on the other side of the door. “Yes, can I help you?” my mother asked. The female officer held a copy of my father’s state ID to my mother’s face. “Ma’am, do you know this man?” My mother’s scream was something I truly will never forget: “What happened? What happened?”

“We don’t know for sure yet, ma’am. All we know is that he was shot. That’s all we know. Do you have anyone who can follow us and drive you to the hospital?” said the male officer, with a softer tone than the woman. “Yes!” said Remal. Remal ran upstairs and told me to call my aunt, who lived a block away. Seconds later, my aunt was in front of our house. Remal hugged me and said, “Enal, take care of akhoutie. Make sure they stay asleep, and just watch over them.” She tightened her headscarf and flew down the narrow stairs. I didn’t see my mother before she left, but I looked out the window as the police car drove off, and my aunt followed.

Shot. Man, I hope it’s not bad, I thought. I was shaking. But what’s the worst that can happen? He came home just last week with a black eye and a bloody lip. On his way out, after he had locked the doors with four locks and two chains, someone was waiting for him on the corner. They took his wallet and beat him up. He came home from work and said, “Very soon…one day…we will go back to our village in Palestine, pick our vegetables from our own gardens, and live in peace.”

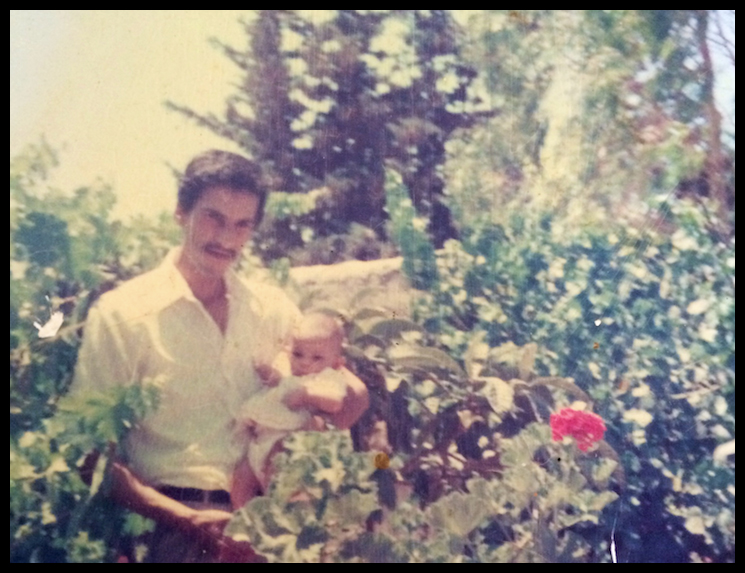

My father was a dark, skinny man. In the winter, when he would walk through the doors after work, his big nose was always red and watery. He was a country boy, born in Al-Jadeera, a small village near Jerusalem in Palestine. When he was, twenty-six years old, he left his family and his land full of rich olive and fig trees to come to America for job opportunities. When my siblings and I were young, growing up in Chicago, my father used to tell us he had planted pomegranate and citrus trees back in Palestine for us to enjoy anytime we decided to visit. The fig trees were for my mom—her favorite fruit. My father loved his figs and pomegranates. He told us his favorite part was picking them off of a tree he planted in his parents’ garden. When I started sixth grade, we moved back to Palestine. My father enrolled us in the village school. We couldn’t afford the private school in the city that tailored to English speaking students, educated in the United States. My father walked into the principal’s office and explained why holding us back a grade level would be extremely detrimental to our education. “They will try to keep up in Arabic with the rest of the kids. If they don’t by the end of the semester, we can talk. But they are smart girls; I know they will keep up.” My father knew the significance of keeping us in our grade level, even if all the classes in the village school were taught in Arabic. Thanks to him, we transitioned into our appropriate grade levels, and never missed a grade. He spent many hours helping us with our homework, translating from Arabic to English and vice versa. He assigned extra readings and asked us to transcribe long stories in Arabic to improve our grammar and writing.

That summer, I sat next to him on the steps of our balcony overlooking our land with groves of olives, and fig trees. He said, “There’s nothing more beautiful than nature, eating freshly picked fruits, and walking in the dirt of your grandfather’s land.” For a year, we watched the land change colors with every season and the trees come to life with care of my father and grandmother. Vibrant, with plump red pomegranates in the summer, old bed sheets and towels underneath the olive trees to catch all the olives in the fall, limes and clementine in the winter, and budding flowers in the spring. We picked fruit, helped babba plant the citrus trees out front, and watched him help his mother during the olive harvest season.

One day, when I was thirteen, I overheard my parents talking. My mother, crying, said, “But what about school? How can they get an education if all the schools are closed?” I knew something was wrong, but I didn’t know how terribly tragic, and imminent it was. The second intifada had started, and the village school, along with many other schools, closed down. My father looked worried and stressed. His eyebrows were scrunched together. He didn’t want to go back to the United States. He wanted to stay in Palestine, but they both knew that staying in Palestine during the intifada meant no school for us, and no school for us, my dad knew all too well, meant a harder life. As the intifada grew worse, with many days being held captive in our own home with the strictly implanted curfews, our hopes of the schools re-opening dwindled. Finally, my parents decided to move back to the United States.

There was a shift in my father’s tone when we moved back to the Southside of Chicago. Whether it was the longing for his family, or the guilt he felt for leaving his mother and sisters in a war-stricken country for a better life, the glow in his eyes dimmed. He returned to his job at the restaurant. The streets of Chicago at night didn’t greet him the same way the olive groves did. He worked long shifts, and didn’t really have time to socialize. The dirt underneath his feet that nurtured the fruits he wished would nourish us turned into cold cement with cigarette butts, old stains of gum, and liquor bottles.

His customers weren’t the most loyal people in the world. I once saw a woman say to him, “Um, there was a long-ass piece of hair in my fries, I want my fucking money back motherfucker!” as she slammed her half-eaten burger and small fries against the bulletproof glass that stood between him and his customers. My father threw the $6.50 through the small sliding-glass window and didn’t say anything. How could he explain that no one worked there but him, and his short hair was always covered in a net? He put one hand on his hips and shook his head in despair, “La hawla wa la qowata ila bila” he said. There is no power or strength except through Allah.

He loved okra. Freshly picked okra. A few weeks before he was murdered, he took us to the Chicago Botanic Garden to “view” the vegetables, although we all knew he wasn’t just going to view them. Just across from the small strawberry fields at the Gardens were the parsley family and okra. He kneeled down and broke off one small okra, “You see this? Your mother will fry it with onion and olive oil tonight and make me the happiest man” he said with a mischievous smile. I saw that glow in his eyes again. “If we were back in the village, we could just go to our back yards and pick as much okra, cucumbers, peppers, tomatoes, and just about any other vegetable you can think of!” he said as he wrapped the okra in a napkin and placed it in his pocket. Jaffer said, “I’ll go back with you to the balad, babba!” and babba’s replied, “Here’s the man of the house, he knows that the peace in the balad is better than anything here.” After viewing (and picking) vegetables throughout the garden, we ended up in an apple orchard. It was beautiful. Green, red, and yellow apples hung on straight rows of trees. We were the only ones there, and we just picked apples and ate. My sister Methal was sad because no one paid any attention to her. My father put her on his back and walked throughout the orchard allowing her to reach any apple she wanted. She smiled so much when she would ride on his shoulders. On the ride back home she said, “Babba put me on his shoulders and let me weach da apples.” My brother Issar, jealous, said, “So, we picked apples and climbed trees, but you’re a baaaaby.” Babba secretly enjoyed the bickering.

I recited a few verses from the Koran in my head and paced around the house. What if he’s paralyzed? Man that would be really bad, I thought. Who would help me with my math homework? Babba was good at math. He taught me how to multiply two-digit numbers. In fifth grade, I stayed up late to wait for babba to check my multiplications. I was still shaking. I visited my siblings, all four in one bed, in one of our two bedrooms. They’re peacefully asleep; the boys cuddled under one blanket, Nehal under her own turquoise blanket, and Methal clutching her pink princess blanket. The phone rang. It’s my aunt. “Get ready,” she said. “Wake the kids up. I’ll be there in five minutes to pick you guys up, we are all going to the hospital.” She hung up right away; before I could say okay. I woke akhoutie up. They were very sleepy and hard to rouse. I tried not to cry as I said, “Wake up, hurry, wake up.” “Why? Where are we going?” asked Jaffer, eight years old. “Something happened, just get ready,” I said. I woke two-year-old Methal. She’s the baby, babba’s baby. “Drum sticks!” is what my father called her legs. He loved to softly bite her skinny legs. She was amazed at the light marks he left. She would say, “Babba gave me a watch!” because the bite marks were round. My dad would draw tick marks and numbers in Arabic and would ask her what time it was. “It’s night o’clock,” she’d respond, laughing. I picked her up, her sleepy head wobbled. I put on her jacket. She’s in socks. She won’t be needing shoes, I thought, since I’ll be carrying her. I pulled a scarf from the closet and placed it on my head. I heard someone honking outside, so I grabbed the house keys, with Methal on my hip, and followed the other three outside.

We drove to the hospital. No one said anything. It was pitch black and the leather seats in the car were cold under their warm bodies. Methal was asleep on my lap, and Nehal, Jaffer, and Issar were in back, afraid to ask any questions. We got to the hospital and frantically looked for my mom. I found her sitting, almost slouching, on a chair in the waiting room, her head tilted to one side. Crying. Her arms hung beside the chair, not having the strength to fix her headscarf, which was nearly falling off. Remal was sitting on the floor tightly hugging my mother’s leg and crying.

I dropped Methal, not noticing how hard she hit the ground until she cried.

I ran to my mother and screamed “What happened?” She looked at me, and without moving her head yelled, “Ya’ni sho? Mat! Abouch Mat!” What do you think happened? He died. Your father died! I froze. Died? How can he die? People on the news die. Not my father, not the man who worked every single day to support his family. It hit me: death. Death means that he’s gone, he’s not breathing, he’s not moving. Maybe it’s a mistake. Maybe he’s actually breathing, but they just thought he died. Death is for the people on the news, who do bad things, who get into trouble, like steal, or deal drugs, or fight. Death? How can a man who is working in a fast-food restaurant die? That’s not true. He’s not dead. How can a man who left his country, his parents, his siblings, his land full of rich olive and fig trees, who left everything he owned just to come to America, the land of opportunities, to work to support his family—how can that man die? Oh my God: My father died. He was murdered. He was shot. He’s gone. I fell to the ground next to Remal. I screamed. My hijab fell off.

The kids were looking at us with their sleepy eyes, confused. Methal was crying because she was sleepy and still sitting on the cold hospital floor. All of the nurses stopped what they are doing and stared at us. One nurse had her hand over her mouth and a look of horror. I started to recite Ayat el Qursi from the Koran in my head. Allahu La Ilaha Ila Huwa al Hayu Al Qayum I held on to my mother’s leg, crying. I smelled the bleach.

“I want to see him! I want to see what you did to my husband!” My mother stood up and walked toward the doctors passing by. I got up, held Methal again. Remal told the rest of the kids to sit down. “Ma’am, we can’t let you see him right now.” The doctor said in a firm voice. “We still didn’t clean all of the blood or run any tests. We need to run tests, and no one can see him now.” My mother screamed, “Tell him I don’t care, tell him I want to see him.” I told the doctor that we wanted to see our father. The doctor said, “Ok, follow me”.

My mother entered first. She ran to him and then fell to the ground beside his head. She held his hand. “Shawqi, why did you leave me? Why? Why did you leave six kids? Come back”, she lightly touched his face, “Wake up! Come back!” We each walked in, in single file, waiting to witness our last image of babba. There he was, the strongest man I know, lying on the hospital bed, not moving. His eyes were closed and he was in his work clothes. They were dirty; his shirt was full of blood. He was still wearing his shoes, He smelled like French fries and burgers and old frying oil. His lips were motionless. His dark lips couldn’t utter anything; did he want to say something to us? I had never seen his lips, which were dark from smoking, motionless before; he was always talking. “Babba, smoking can kill you, stop smoking babba, please,” all of us kids would beg. “I’m gonna end up dying anyway, might as well speed up the process,” he would say after exhaling white smoke out of his large nostrils, with a smirk, half angry that we are telling him what to do, half happy that we feared for his life.

I went up to him and touched his body. It’s stiff. Was he really dead? Why can’t I believe it? Maybe he’s just pretending, or maybe this is one of those miracle stories that happen to good people. Allah would never do this to us, I thought. It must be a miracle story! Good people have miracles. Unbelievable miracles that are too good to be true. Isn’t this the part where he wakes up in pain and says “Methal, can I bite those drum sticks?” And then my mom cries because she’s so happy, and my siblings still don’t know what is going on, but are happy to see babba. And I pray so much and thank Allah so much for this beautiful miracle. And my dad tells us the whole story, making it dramatic so that we can see what an amazing hero he is. And we all go to Wal-mart, as planned, and buy all of our school supplies. It’s the second week of school, and babba told momma to wait after he gets paid to do all of the school supply shopping. He promised us that we could go Monday after school. And then we could all compare our colorful notebooks and tell our friends what a bizarre weekend we had. Yes. It’s a miracle story. When is he going to wake up? I have Methal, she’s ready to have her drum sticks bitten by you, babba, come on wake up!

He didn’t wake up.

Maybe he really did die. I felt his shiny, olive-toned forehead. He was cold. My mom was still crying. “Wad’oo babba ya woad,” said my mother. Say good bye to your father kids. It hit all of us. I didn’t want to say goodbye. How can we say goodbye now? I saw him this morning, before I left to school. Will I see him again? We all cried and kissed my dad. Maybe now the miracle happens. I kissed my dad hard. I pressed my lips, almost angry, hard, kissing hard. ‘Wake up babba, wake up, I’m kissing you to wake up.’ I kissed harder. Wake up babba. Harder. Wake up babba, harder, harder, harder, wake up babba! He just lay there, peacefully, in his blood-stained work clothes.

Forty-eight dollars and fifty cents. That’s how much the robber, the murder, took. He shot my father in the chest for $48.50. This must be a miracle story. Because when babba comes back, we can all say how callous bad people are and babba can teach us a lesson about money and life. This is the perfect miracle story! How can someone take babba’s life away for $48.50? They can’t, because they know it’s not worth it, they were just playing the bad guy in babba’s hero story.

After spending the night in the hospital, Remal and I went back to our house. “Clean out the house, make sure none of your father’s belongings are there to remind your mother,” my Uncle said to us. We packed up his clothes from his dresser and closet in a large black trash bag. We cried, but didn’t say a word. I looked in the bathroom; all of babba’s clothes were waiting to be wrung out to dry behind the stool in the bathtub. I wrung. Hard. My tears fell on his wet clothes and Remal brought in another black trash bag. I threw them in the bag.

We walked into their bedroom. Their bed was made. It was simple. A bed, a nightstand, and a dresser. It seemed a lot bigger now. A glass of Arabic coffee sits on the nightstand from the thrift store. The coffee was dried up; it solidified at the bottom of the glass. It must have been from Sunday morning. I smelled it. The aroma of thick Arabic coffee is not the same without the smell of cigarettes. I’d never smelled the coffee without the smell of babba smoking. Babba always drank Arabic coffee and smoked at the same time. I took it to the sink and rinsed it out. I placed it to dry on the rack. Maybe it’s one of those miracle stories. Maybe babba will come back tonight, and I’ll make him Arabic coffee. And he will drink his coffee and smoke, and we’ll scold him for smoking, and he’ll smirk.

We’d never been to a wake before. I wonder what people do at the wake, I thought to myself on our way in the car. I wonder if people will be there, or if it was just us. I wonder if babba will be there. I walked inside the funeral home, Methal on my hip and my mom’s hand in my mine. I thought funeral homes were for rich people who plan their deaths in advance. I didn’t know normal people come here too. A sign on top of the room says “Hindi.” Oh my God, I thought, that’s for my dad. It must be true. Allah knows that babba is all we have. Allah would never leave us on our own. Maybe we are dying at the same time and we just don’t know it.

We walked inside the room. It was full of people. Do they think that my dad died too? They must, because they are all crying. I froze. My heart stopped. I couldn’t blink. A coffin? Is that even legal in Islam? My babba is inside a coffin? Why isn’t babba wrapped in a white cloth, the way we are supposed to meet Allah’s angels of death? The Koran is playing loudly, Juz’oo ‘Amaa to be exact. I knew this Juz’oo by heart. The voice too, I knew this voice. Sheikh Abdul Rahman Al-Sudais, Leading Imam of the Grand Mosque in the holy city of Mecca. I loved his voice. I grew up with it, as my dad would always put on the Saudi Arabia channel and leave it playing Sheikh Al-Sudais recitation of the Koran as we waited for momma to bring the dinner to the living room.

Every time we watched Al-Sudais recite the Koran babba would say, “Do you know how to read like that? I wish you did. You know, he memorized the Koran at the age of twelve? Did you know that the person who memorizes the entire Koran will go straight to heaven?”

Al-Sudais voice was thunderous inside the funeral home, I was blessed to have memorized some of the verses. I didn’t understand much of the vocabulary of the Koran, but somehow, when hearing Al-Sudais recite the words of Allah, I would have this certain feeling, a certain type of melancholy. Not depressing sadness, but beautiful, peaceful, grateful sadness. A nature of sadness that instilled in me a few existential questions at an early age. Why are we here? What is the purpose of life? What mattered most? I didn’t know, but this time, the melancholic recitation, my father’s body, and these questions all aligned under the same angle of a prism, twisting inside me, juxtaposing one another as answers. Al-Sudais’s voice is so soothing, like breath exhaled on a cold winter day. It’s serene, sad almost. It was the only thing I could hear. Surat Al-Naba. I knew this surah. We had just memorized it in Saturday Islamic School. I recited along with Al-Sudais in my head. My insides were hurting, there’s something answering one of these deep questions I’ve had, and I look at my dad. I don’t want an answer yet, not now. But the recitation penetrates deeper, and somehow the worldly and the ethereal somehow meet. The line between reality and the metaphysical was disappearing, and I am desperately escaping reality, chasing the metaphysical. I recited the verse in my head as I sat on the floor, hugging my mother’s leg.

It was babba’s wake, or was it his funeral? I didn’t know. I couldn’t tell the difference. Nonetheless, babba was in his coffin. Jaffer and Issar were playing tag with my cousins. Issar just graduated from kindergarten two months ago. Babba only wanted to buy him two balloons, but momma thought that wasn’t enough. She bought four colorful balloons that read, “You did it!” and “Congrats Grad!”

In the one picture mamma took of babba with Issar at his graduation, babba frowned. Issar didn’t know that was the last picture he’d ever take with babba. Now he was running around the funeral parlor screaming, “It! You’re it! I got you!” Jaffer chased him along with my other youngest cousins. Issar pushed Jaffer with his Chuck E. Cheese’s–stamped hand over and Jaffer bumped into the coffin. Babba had taken us to Chuck E. Cheese’s days earlier. They circled the coffin, trying to win tag, around babba. Methal was asleep on the ground next to me; a nice lady, perhaps a family friend, covered her with her lavender sweater. Nehal sat next to me and Mamma and Remal, hugging mamma’s other leg. Nehal was eleven years old. She always complained to babba how she was the “ignored middle child” of the family. “No no, you’re only the middle child,” babba would say. “I try to ignore all of you!”

For hours, we sat. Methal asleep, the boys playing tag, my mother crying. The last thing I remember is holding Methal to give babba a kiss good bye. “Bosee babba Methal”. Kiss babba Methal. “He’s cold and smells,” she said scared and crying. I held her. I leaned and gave babba a kiss. He did smell. He was cold. His face was not soft and flexible, but still, motionless, hard. There were no creases around his eyes. His wrinkles were all gone. His mustache looked fake. I wanted to see that glow in his eyes, but I touched his face gently and said, “I love you.” I wanted to know what he was thinking.

I know what he would have told me: Allah tests those he loves the most. Allah tested my family. Allah knew that at fifteen, I could handle seeing my babba covered in blood. Allah knew what could break us and what can strengthen us. Allah knew that babba’s murder will never break us. Allah knew our love for our mother can never be measured in this world, and we can only see it through these eyes; the very eyes that saw babba in blood that night. Allah knew that, in the years after his death, momma’s strength would build six characters, six bodies, six souls; that she would and smile every day and sleep alone at night, praying for her husband. Allah knew that my mother will only open up the gates of paradise for her children and husband. Allah knew, but did I?

A few summers ago, my family and I returned to Palestine. My belly was round and and taut. I was expecting. The figs were ripe and the dirt was smooth. And just as my dad had promised, the trees were larger, their branches hanging low with their grown fruit.

She has your eyes, Baba. Her name is Elya. The name of a sacred place that only you and Allah know.