All photos by Johanna Benainous

In the era of Google Image search and KonMari minimalism, the prospect of two million printed photographs seems like an unmanageable mess of analog culture. At the headquarters of Roger-Viollet, one of the oldest photo agencies in France, these photographs were confined to a suite of eight narrow rooms, each stacked floor-to-ceiling with green cartons, each carton filled with envelopes of photos. Every surface was crammed with these boxes, the doorways squeezed in as an afterthought. For a space dedicated to photography, it was somewhat spare: only a handful of images were on display. Framed behind the vitrine there was a picture of two women laughing at a café; on a rare span of open wall, a shot of a horse eyeing an ice-cream cart.

Even if you’ve never heard of Roger-Viollet, you’ve likely seen the photographs in its vast collection. In addition to the two million printed images at its Rue de Seine building, the agency holds four million negatives and other more fragile media, including photographic plates and celluloid-based film, at another site near the Bastille. Its reserves come to more than six million works. The agency operates as a Getty Images of French history—and a visual encyclopedia of events the world over—from photography’s origins in the early nineteenth century to the 1980s. Some of the most famous include the surrealist nudes of Laure Albin-Guillot, Janine Nièpce’s images of the women’s movement in the Seventies, and Boris Lipnitzki’s iconic portrait of Coco Chanel, a string of pearls dipping between her shoulder blades.

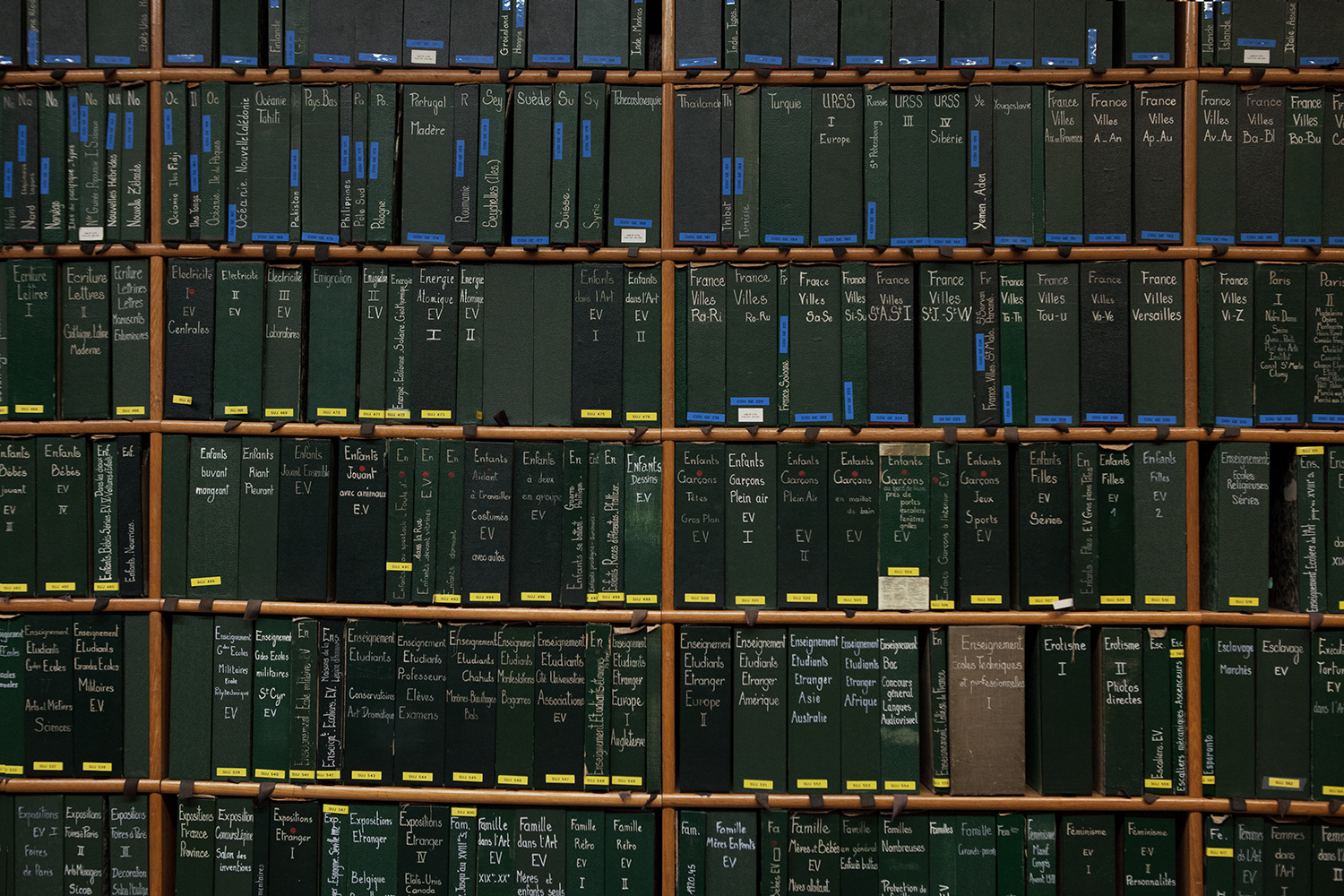

When I visited the agency, entering through the glass door of an apartment building surrounded by blue mullions, I was surprised to learn that the tidy green cartons were not filed by photographer, but followed an idiosyncratic catalogue of subjects. Yellow, blue, and white stickers indicated various organizing schemes, with keywords handwritten in white: frescoes from the middle ages; agriculture-mushrooms; history of the revolution. The sheer scale of the archives underlines the challenge of their preservation. Without regular upkeep—cleaning dust, filling in holes, regulating pH and humidity levels—the negative as material object is at risk.

I started learning about the agency’s strained financial resources last summer as I passed by its windows on my way to work. “No to the closure of Roger-Viollet by the City of Paris,” a banner read in red spray paint. Roger-Viollet was under review after an audit revealed that it had surpassed its budget by five hundred thousand euros. Protesters insisted that it should not be shut down. “We do not want to end up like our most famous image, of the train that crashed at the Gare Montparnasse!” an employee anonymously told Le Monde.

Due to insufficient records (and perhaps to French etiquette discouraging direct talk about money), it is unclear when Roger-Viollet last turned a profit. When the agency came under the management of the City of Paris in 1985, it was already deeply in the red. In 2005, the company Parisienne de Photographie was created to reduce Roger-Viollet’s ongoing financial difficulties and oversee the upkeep and distribution of the archive’s photographs. As images circulate for free online, economic losses run deep in the industry. In 2017, French President Emmanuel Macron reduced government funding for the City of Paris, the primary benefactor of La Parisienne-Roger-Viollet. The company was given the directive to make ends meet independently of the city’s funding. Bruno Julliard, the secretary of culture for Paris, nevertheless renewed government financing, mitigating the threat to Roger-Viollet through December. But this is just a temporary fix. Nicolas Bouillant, who took over as the agency’s new director last year, is tasked with charting a new way forward.

Click anywhere on the image to enlarge

Roger-Viollet was founded in 1938 by Hélène Roger-Viollet and her partner Jean-Victor Fischer, both amateur photographers. To build their collection, they purchased works from journalists and scoured flea markets and private collections, sometimes paying only one franc for a photo. Instead of investing only in celebrity snapshots and pictures of headline-making events, Hélène and Jean-Victor wagered their money on images of everyday life.

This year, for the fiftieth anniversary of May 1968, when students and workers revolted across France, Roger-Viollet curators culled its reserves documenting the events, including those of France-Soir, then the most widely read newspaper in France. Among the images of protesters throwing cobblestones and setting the stock exchange on fire, one shows students hanging out at the Place de la Sorbonne: sitting on a barricade as if in armchairs, they look bored. All of them avoid the camera except for a lone figure in the back, who stares straight at the lens.

This was the kind of photo Hélène and Jean-Victor looked for—candid gestures, what Walter Benjamin called a “tiny spark of accident,” that would normally not make it into the official record. Roland Barthes would famously theorize this idea as the “punctum,” a striking gesture or camera angle that captures the viewer’s gaze. The couple collected excessively. It was then standard practice to select one or two images; they would instead acquire the whole reel. Delphine Desveaux, the manager of the collections, told me that many photographic sequences in the archive are seamless enough to form a movie.

Little is known about the lives of Hélène and Jean-Victor. The few clues that remain are hidden in their collection. While on vacation in Cuba in 1959, Jean-Victor took a picture of Hélène sitting on a rooftop with two militants carrying machine guns. Smiling at the militants, she wore a long floral dress and pearls, her short brown hair blown by the wind. Then, the perspective is reversed; in Hélène’s photo, Jean-Victor showed his camera to two other Cubans, opening it up like a magician showing how he pulls his tricks. The couple appeared unidentified like this in folders labeled “Children,” “Voyages,” and “Family meals,” presumably because their images would sell better as anonymous stock figures.

In January 1985, Jean-Victor was found on the street outside the agency, both his wrists slashed. He led police to the apartment he shared with Hélène, nearby on the rue des Beaux-Arts, where they found her dead with a slit throat. As the legend goes, Jean-Victor survived long enough to admit to killing her as part of a planned double suicide. (He later killed himself in prison.) In their joint will, the couple left everything to the City of Paris, stipulating that the Roger-Viollet collection continue to be conserved and disseminated.

Click anywhere on the image to enlarge

Unlicensed imagery on the internet and the subsequent loss of copyright fees has threatened the agency’s financial standing. But the current media industry places a premium on digital reproduction, and a material medium puts the image at risk of deterioration. Since the late Nineties, a portion of the agency’s team has steadily been making digital records of the pictures. So far, just over 550,000 images have been committed to an online database. Blown up on a screen, the photos reveal new details: shadows, silver particles, and drops of chemicals from the dark room.

Desvaux, however, told me she believes that the physical prints, even if difficult to store, catalogue and maintain, will be what allow the photographs to remain relevant. “Proven by over a century of practice, the long time frame of the collection will endure because these images are preserved as objects,” she says. “When the digital copies are lost—as they inevitably will be—we can return to the source and remake them.”

Bouillant, on the other hand, is investing in digital. He wants to make the collection as visible as possible on multiple platforms, working with a model that partially foregoes copyright fees. “Of the 550,000 photos now available on the agency’s website, almost half of them are free.” For historical and patrimonial pictures, which are Roger-Viollet’s primary asset, Bouillant tells me, “When they’re free, there’s a snowball effect that creates more value.” A smartphone app is in the works.

Both are right, in a way. Scrolling through an endless supply of images is not conducive to what might be offered by a picture on the second or third take—the revelation of the subject hiding in plain sight. Digitization seems to be at odds with Roger-Viollet’s legacy, all that history stored away in boxes of “tiny sparks.” But the way we consume images has changed so dramatically over the past decade that nowadays a physical photograph without a double on the screen is just as good as lost. No matter how true it is that the archives ought to be conserved, these pictures do not pay for themselves.

Bouillant is not immune to the material charms of the Rue de Seine headquarters. He opened the space to the general public earlier this year and hopes to start selling prints soon. Christopher Charpaud, the Manager of Sales to Private Customers and Visitors, told me that so far, visitors have been thrilled by the chance to sift through the archive’s black-and-white images. “All these boxes,” he said, “people find it magical.”