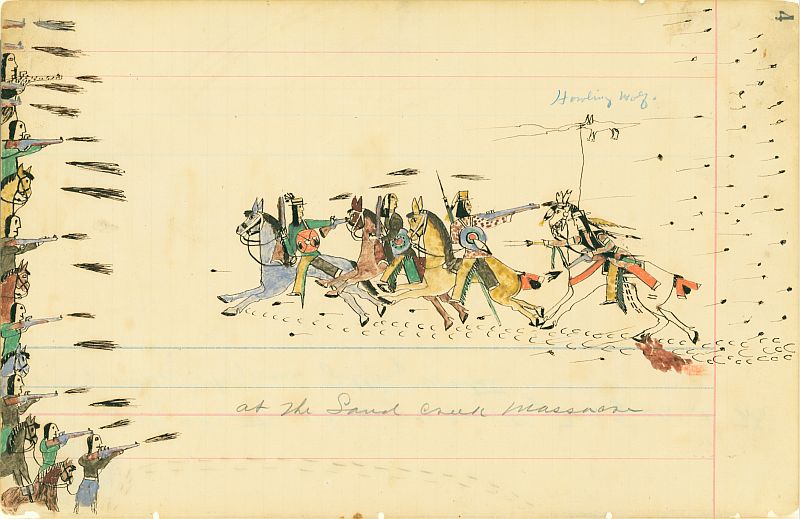

Depiction of the Sand Creek Massacre by Cheyenne eyewitness and artist Howling Wolf, circa 1875

Kiowa County, like so much of southeastern Colorado, has for most of its history been a place to be passed through—an eighteen-hundred-square-mile rectangle of unbroken wind, horizon, and short-grass prairie. For a generation of white settlers, streaming west on the Missouri Pacific Railroad after the Colorado gold rush of 1859, it served as a vast natural highway, guiding hundreds of thousands of homesteaders out of the featureless plains and to the foot of the Rocky Mountains. What few travelers did endeavor to stay here farmed, and by 1902, eleven whistle-stop towns had grown up along the route, where, in the town of Chivington alone, one found a newspaper, seventeen saloons, and the Kingdon Hotel, then considered the most magnificent stay west of the Mississippi. Utterly reliant on the railroad and local farming boom, however, the county soon went bust in the selfsame way as the railroad and local farmers: spectacularly and all at once. Overnight, whole towns stood abandoned, the Kingdon and other buildings dismantled for scrap. As the Dust Bowl rolled farther west, riders on the last outbound trains scavenged what they could and wrenched up the railways behind them, leaving little of record but roadside markers commemorating Kiowa County’s proud role in the founding of Colorado. And for the next hundred years, the county once again numbered fewer people than it did square miles. Today, in the county seat of Eads, population 590, one finds two motels, a drive-through liquor store, and one high school, which for many years fielded a six-man football team.

One day in 1999, a fifty-five-year-old barber and journeyman mechanic named LaForce Lee Lonebear arrived in Kiowa County with a caravan of nearly five hundred friends and relatives. As a member of the Northern Cheyenne Nation who once roamed the Colorado plains, Lonebear was that day a visitor to his ancestral homelands; he’d grown up and lived, as many modern Northern Cheyenne had, some seven hundred miles to the north in Lame Deer, Montana, on the tribe’s seven-hundred-square-mile reservation, where he would eventually serve seven terms on the Tribal Council. Lonebear, who died in 2011, was a proud Cheyenne—a powwow singer, a traditional healer, an “Indian Ball” coach—who for much of his life had dedicated himself almost exclusively to a single cause: the spiritual healing of his tribe. Together with other representatives from the Southern Cheyenne and Northern and Southern Arapaho, he’d worked for more than fifty years to honor the memory of his great-great-grandfather, Chief White Antelope, and great-grandfather, One-Eye, both of whom, along with hundreds of others, had been murdered in Kiowa County more than 150 years before. Although it wasn’t then commemorated in the state historical society or on any roadside sign, it’s a story most any American Indian can recite to you by memory.

Just after dawn, on the morning of November 29, 1864, 698 mounted soldiers of the US Cavalry under the command of Colonel John Chivington stormed into a peaceful village of Cheyenne and Arapaho camped along the banks of the Big Sandy Creek, some thirty miles northeast of Eads. Roused from his tepee, Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle scrambled to raise a white flag over the village, along with an American one gifted to him by President Lincoln—the signal taught to him by the military to avert any violent misunderstanding. Over the last few months more than eight hundred people had come to gather at the creek, led there by thirteen different peace chiefs, including Black Kettle and White Antelope, who’d had been invited by the territorial governor to participate in new treaty negotiations. Assured of their people’s safety, the chiefs had sent nearly all the male warriors out hunting, leaving the village exposed. It was quickly overtaken. In a running skirmish that lasted some three days and fifteen miles, the soldiers eventually slaughtered between 200 and 300 people, most of them escaping women and children, who, with nowhere to hide on the winter prairie, tried burying themselves in the frozen sand. In the end, so systematic was the killing that few details survived the day save for those recorded in soldiers’ notebooks and passed down in escapees’ oral histories.

For the Cheyenne and Arapaho, the lands of the Sand Creek Massacre, as the violence became known, were sacred. Since the military had either burned or discarded every body on the prairie that day, taking ears and scalps for trophies and later shipping bones back to Washington for study, the tribes believed their ancestors’ souls were still troubled, robbed of their final burial. This was why Lonebear and the others had traveled to Sand Creek; in order to help their ancestors’ spirits ascend, they had organized what they called a “spiritual healing run,” in which the descendants would pray and sing over several days as they made their way some two hundred miles to the state capital in Denver, where many of their ancestors’ body parts had been paraded in bars and theaters. The route they chose was itself expressly symbolic: it took the runners first by the town of Chivington, established and named for the colonel more than twenty years after the massacre, then parallel along the route of the old Missouri Pacific Railroad, before finally turning northward within view of the gold fields—the descendants tracing roughly the same path so many white settlers had once taken through their lands. The county thus began, over the next fifteen or so years, to enjoy a kind of second rebirth—this time as a pilgrimage site, as many hundreds of indigenous people from across the country and world journeyed there each November to honor the dead. Unsettled by this sudden revision of their local history, white locals didn’t know how to greet the tourists except to resist the idea of their hometown becoming known as “a massacre site.” We understand what happened, they said. But this is our home. Lonebear and the other founders, including Otto Braided Hair, heard them, and were sympathetic.

“For us, everything is healing,” said Braided Hair. “We say it is our tribal history, but it is not. It is the history of the land.”

The inaugural run had followed some fifty years of bureaucratic haggling over the creation of a more permanent ceremonial site. Although Bill Clinton had signed the “Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site Study Act” the year before the first run, authorizing the national park service to begin surveying along the creek for a site to be purchased on behalf of the tribes, the project had run into difficulties. There was 9/11, for one, which immediately dimmed the political prospects of a monument against American military violence. But also the trouble of locating the exact site of the massacre itself, which had lain buried, in more ways than one, for nearly 150 years. Military maps and tribal histories seemed to point to one of two sharp oxbows in the creek—Dawson South Bend and Dawson North Bend, respectively—but no archaeological dig had so far turned up definitive signs of violence at either. Archival evidence pieced together from land and road records, as well as aerial photography and geomorphological studies of area streams, eventually helped narrow the search to Dawson South, but contradictory clues and readings persisted—disagreements further complicated by tribal descendants who, after hearing ancestral voices at the innermost crook of Dawson South, declared it sacred earth. Eventually, an archaeological dig discovered horseshoes, bowls, and munitions at a broad clearing just north of Dawson South, where in 2007 the park service broke ground on the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site.

One of the first projects was a burial ground. In the years since the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, in 1990, Lonebear and others had worked tirelessly to recover their ancestors’ skulls, bone fragments, and scalps from historical societies, museums, and private collectors. According to tribal belief, each severed body part still carried with it the restless soul of its person, which could not be released until properly buried in the grounds of Sand Creek. As the tribes labored to inter the first repatriated body parts in the burial ground, others soon began arriving at Sand Creek by way of military descendants, some of whom escorted the body parts back to Sand Creek with help from tribal leaders. Some descendants denied knowing what the objects were until contacted by the tribes; others said they’d been passed down, generation after generation, as family heirlooms. One of the descendants, Michael Allen, told of how his dad remembered, as a small boy, seeing a scalp on the wall of his grandparents’ home, hanging between the kitchen and dining room. Whatever happened to it, Allen never learned. But many years later, in his father’s dresser, he uncovered a silver, bird-shaped amulet. A tribal representative told him it still carried with it the soul of a Cheyenne warrior. Returning it would hopefully mark the beginning of the his soul’s long passage. But somewhere outside Branson, Oklahoma, on the way to Sand Creek, the amulet fell out of Allen’s car, and was never found. How many others like the warrior had likewise been lost, destroyed, or remained hidden was impossible to know.

One day last summer, I traveled to Sand Creek to see the site of the massacre in person. I’d grown up in Colorado, but farther north, along the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains, and was struck, in 2014, while reading about Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper issuing the state’s first public apology for the massacre, by just how little I actually knew about Sand Creek. I found I couldn’t so much as place it on a map. A founding legacy of my home state, where more than 250 people had been killed. It had become a point of shame. And what few details of Sand Creek I did possess, I realized, had come from a family copy of Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, Dee Brown’s famous “Indian History of the American West,” which my mother gave me when I was fifteen or so, the same age at which she’d first discovered the book. Until then, and for as long as I could remember, she’d kept her copy displayed prominently alongside a few other cherished photos and mementos in a glass-fronted cabinet near her desk. Brown’s chronicle of the Native American genocide had been a revelation to her when it came out in 1970, she and the rest of the country then only a few months removed from the shock of My Lai. Although my family never claimed any deep generational, let alone indigenous, ties to Colorado, Sand Creek had forever after held a certain prominence in my mother’s sense of place. As, I gathered, she hoped it would for me.

The Sand Creek National Historic Site, which lies about two hundred miles southeast of Denver, is spread out amid more than 12,500 acres of decommissioned and privately owned ranchland that still looks every bit the part. The landscape is windswept and almost geometrical in its starkness: in every direction a flat expanse of grass runs to the horizon, broken only occasionally by a fence post, stock tank, or the thin ribbon of cottonwoods that snakes along the creek’s meander. When I pulled into the dirt lot just after breakfast, the day was already windy and north of ninety, the sky that ashen shade of blue you get from risen dust on the prairie. I was greeted by two of the site’s staff, Shawn Gillette, the chief of interpretation, and Karen Wilde, the tribal liaison, who led me past the site headquarters—a doublewide trailer selling magnets and books and flanked by two informational placards and a tornado shelter—and into a conference room, which was cool and slashed with light. There were flags from Sand Creek’s represented Indian nations on the walls, along with framed historical documents, paintings, and portraits, one of which described the life of Chief Lean Bear, who was killed by the cavalry in the months leading up to Sand Creek, after riding out to a parlay wearing a peace medal given to him by President Lincoln. The room was a de facto mausoleum, stocked with reminders and remnants of what happened on the plains. “Death is what we talk about here,” said Wilde. “That’s why this is a park unlike any other.”

She didn’t mean this idly. Among the park service’s 418 sites, Sand Creek is the only one dedicated to an act of mass murder committed by the American government, and it remains, far into the age of mass shootings, the only government site with the word “massacre” in its name. It’s a singularity the staff treats gravely. Gillette and Wilde often took pains during our talk to point out that the term “massacre” wasn’t the tribes’ or park service’s designation, or even a modern one, but in fact that of the military and Congress, both of which investigated and declared Sand Creek a massacre as early as 1865. Still, such a word tends to form camps. Over the course of the site’s fraught creation period, chronicled vividly in Ari Kelman’s A Misplaced Massacre, politicians labored through many of the same stages of denial as their counterparts 150 years before—decrying “revisionist” histories and urging restraint with charged words, before eventually submitting to religious soul-searching and gestures of racial pluralism. In the end, Colorado Senator and Cheyenne tribal member Ben Nighthorse Campbell read two letters into the congressional record that swayed the decision. They were by a young Kansan soldier named Silas Soule. They had seemingly been lost since his murder in 1865 before reappearing around 2000. They begin:

I tell you Ned it was hard to see little children on their knees have their brains beat out by men professing to be civilized. One squaw was wounded and a fellow took a hatchet to finish her, she held her arms up to defend her, and he cut one arm off, and held the other with one hand and dashed the hatchet through her brain.… They were all scalped … One woman was cut open and a child taken out of her, and scalped.

Soule’s letters, which contributed significantly to the military’s findings—as well as most probably his own murder—were one of the first, and surely the longest and most graphic, full-text displays ever installed in the park service. Framed in simple wooden housing, the two prints stand near the center of the park’s picnic area, under a solitary stand of cottonwood trees. “They break every rule and recommendation of what the park service says a good exhibit should be,” Gillette said. But nearly every visitor who started reading one of letters usually wound up reading both. Many were too moved to speak, and park rangers who’d previously worked at Grand Canyon or John Muir often found themselves in the new position of comforting visitors. The site’s former superintendent, Alexa Roberts, told me that the park was working closely with the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, including D.C.’s Holocaust Museum, on the development of a new research center in Eads; she admired the way the education experience of that museum flowed through a grasp of—or rather, an inability to grasp—the atrocity’s magnitude. While Sand Creek does provide your typical twice-daily ranger talk, the staff told me they see themselves more in the mold of Arlington National Cemetery. “We don’t want people to come out here and hold debates and talk tactics,” Gillette said. “We want people to understand what happened.”

Outside, the wind had abated. Following a crushed-gravel path to the north, I made my way up a slight incline onto a bluff called “Monument Hill,” which looked out over the creekbed and meadow where the greatest rash of the killings occurred. In front of me, a sign read, “Help Respect Sacred Ground. Please, Stay on this Side of the Fence.” Conditioned as I was by the grandeur and freedom of movement of other parks, I found myself wondering what, if anything, I was supposed to do and see from this vantage. Strictly speaking, there was nothing: a creek, a meadow, a few scattered cows in the middle distance. The trail I was on continued another mile and a half to the north, running roughly parallel to the victims’ path of flight, but there were no further displays or vistas. The trail simply terminated in a dirt clearing with a bench, a sign on which warned to look first for rattlesnakes before sitting. I’d tried to broach this question with the staff somewhat awkwardly earlier in the day, asking them what, exactly, one was supposed to do at Sand Creek, but the answer still seemed abstract.

Wilde, as it turned out, has made quite a long career out of turning confused little questions like mine into delicate insights into the nature of history and commemoration. A member of the Muscogee (Creek)/Pawnee Nation, she worked for the better part of a decade at the Colorado Commission of Indian Affairs before leaving to join the park service during the site’s planning. As tribal liaison, her job often entailed striking compromises on management and educational matters between the government and tribes, both of whom she’d worked for and alongside most of her career; the job gave the impression of being one of semi-constant two-way interpretation. Reclined back on one elbow, her ranger’s hat tossed before her, she exuded the kind, if weary, protectiveness of someone who’d labored many years against regular misunderstandings. She seemed neither saddened nor particularly surprised by my question.

“It’s about a sense of place,” she said, situating my question in a somewhat different cast of thought. “It’s not about seeing monuments or signs or whatever else a lot of the other parks point out. It’s actually something you have to experience.” And that experience? Wilde couldn’t say, exactly—not for me, anyway. For her, it was partly about giving voice to those who’d been killed, preserving what she could of the many branches or, in some cases, entire family trees cut down in the massacre, along with the stories of those who remembered and cared for them. Her words reminded me of a passage from Tommy Orange’s novel There There, which had initially struck me as somewhat odd. Orange, who is himself a member of the Cheyenne-Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma, called Sand Creek “massacre as prologue.” “Some of us grew up with stories about massacre,” he writes. “Stories about what happened to our people not so long ago. How we came out of it.”

How we came out of it. This is what Wilde meant, I think—that Sand Creek is an artifact, one which itself preserves, in a certain way, the very perseverance of its people. The plainness of the scene before me, in this light, was staggering. For over 150 years, the tribes asked the bureaucracy that destroyed them if they might have back the site of their undoing, if only to bury their dead and attest to having done so. As the Sand Creek brochure explained it, “At stake were two ways of using the land, of seeing the world.” Wilde told me that she could understand how some people might feel burdened by such a solemn responsibility; visitors sometimes expressed astonishment at the horror the rangers managed to recount each day. (At least one ranger recently requested a break and transfer to other duties.) But she saw it differently. “Somebody has to give voice to those people,” she told me. “I’m not Cheyenne, I’m not Arapaho, but my people were wiped out, too. They were removed from their original homelands. I may not know those stories, but I’m here to represent this story.”

One part of that story belongs to a man named Gail Ridgely, a former school principal and tribal-college president from the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming, whose family is descended from the Northern Arapaho clan of Little Raven—the chief thought to have led many of his tribe away from Sand Creek to safety just before the attack. During the initial site study in the late Nineties, the government commissioned park-service historians to gather oral histories from surviving families, in the process recording over two dozen, making it one of the nation’s largest repositories of Cheyenne and Arapaho stories. One of the most lucid came from Ridgely’s father, Eugene Ridgely Sr., or Eagle Robe, who’d previously shown another group of historians a painting he’d made. It was four feet tall and eight feet long and rendered on an elk hide. If you pull up a photo of it online, you can just make out the figure of Little Raven in the far bottom-left corner, fleeing with his people. Since 1998, Gail Ridgely has acted as a Northern Arapaho Tribal Representative for Sand Creek, consulting on the educational practices of the park. It is a role unique to Sand Creek, and one of some influence.

Sand Creek is as much about the spiritual healing of the Cheyenne and Arapaho people as it is about wider educational awareness, Ridgely told me when we spoke over the phone. Growing up, he said, “there was no awareness, no teachings.… mostly it was Pocahontas, Sacagawea, four or five pages,” but nothing more. Although the majority of his life has now been dedicated to Sand Creek, he was nearly seventeen before he learned the details of what happened to his family there. At the time, his only real interest was guitar. He and his two brothers played in a band called “The Native Americans”—an old-style country-rock group in the mold of Johnny Cash and Willie Nelson. (Ridgely went on to play warm-up gigs for the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band and T.G. Sheppard.) One day during a jam session in their garage, Ridgely’s grandfather, a medicine man named Benjamin Goggles, asked them what they called their group, and Ridgely told him. No, he answered: “In honor of your ancestors who died and survived at Sand Creek, I want you to call your band the Sand Creek Band.” It was the first time Ridgely heard that his ancestor, Lame Man, was among those who’d survived. But it wasn’t until Ridgely finally visited Sand Creek in 1993 that he truly grasped his place in this lineage. He felt signs of violence everywhere, he said, and in places even found physical traces of it still on the ground: a brass arrowhead, a broken cavalry picket pin. “That land is sacred,” Ridgely explained, “because the blood, in a way, is still there.” He added, “The blood of the people hasn’t been properly aired.”

This was the point Ridgely returned to most often as we talked—that Sand Creek is still very much present in the lives of its people. It was partly out of this sense of continuity, he said, that the tribes have repeatedly rejected petitions one might otherwise consider bids of “historical reckoning,” such as the renaming of places bearing the names of their oppressors, like the Kiowa town of Chivington, or fourteen-thousand-foot Mt. Evans, named for Colorado’s first governor, John Evans, who was complicit in the massacre. While they see these markers as a legacy of the same American racism evident in certain sports mascots, some are also adamant that America not be allowed to simply expunge the traces of that legacy. In 1998, when the Colorado state legislature moved to excise a mention of Sand Creek from a list of “Battles and Engagements” on the state’s Civil War monument in Denver, it was in fact the tribes who moved to block it, supporting instead the addition of a plaque clarifying Chivington’s actions. History forms in geological layers, the tribes said—you do not get to remove the middle strata out of shame or guilt. You could not separate the creation of that monument from the many years the public took no issue with it, any more than you could separate the clearing of the plains from the impoverishment of Ridgely’s people. His explanation made me think of a passage from Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, which I’d been returning to during my trip. It occurs at the end of the chapter on Sand Creek, after Brown describes the subsequent treaties, all broken, including that of the Little Arkansas River, which guaranteed reparations to the descendants of Sand Creek, but eventually led to the tribes’ forced dispersal to reservations. It reads: “Thus did the Cheyenne and Arapaho abandon all claims to the Territory of Colorado. And that of course was the real meaning of the massacre at Sand Creek.”

Before we hung up, Ridgely took a moment to say how much he still loved the simple pleasure of seeing his homelands, what a palliative it was. “When I go down there, I feel at home,” he said. “Especially when I go across the Fort Collins area—that was Arapaho country—and you can feel ancestors. You feel at ease.” It was the first time I’d heard that my hometown lay on Arapaho ancestral land—a fact made all the more striking by the way I was learning it. Throughout my reporting on Sand Creek, I’d found myself astonished by the sheer enormity of effort it’d taken to make visible a history of such plain destruction. The casual ignorance that underscores so much of America’s attitude toward the indigenous seemed itself like another form of racial violence—to make the explanation of grief the victim’s debt to the wrongdoer. It made me think back to the expansive openness of the park, which I’d come to admire as its most moving and groundbreaking feature. The effect of standing there was stereoscopic: it widened the historical frame, helping you picture in unmistakable clarity the true extent and intent of the violence so recently done there. Ridgely listened to this and clarified a few points of history, before adding, “That’s why Chief White Antelope sang that as a death song: only the rocks and mountains live forever.” Then, as if returning us to a task left unfinished, he described once more what happened to his people at Sand Creek.