Playlist: Hamell on Trial for Beginners

In December 2007, the one-man punk band Hamell on Trial took the stage at Cleveland’s Beachland Ballroom (capacity: 500), to an audience of five. “Wow,” Ed Hamell said, grinning from stage left, clad in new leather boots, worn Levi’s, black T-shirt, and matte-black leather jacket. “I cannot believe you guys made it through this storm. You had no business getting on the road tonight.” He was right. We had driven close to an hour across a thin, slick coat of ice in a storm that frosted roads from Minneapolis to Toronto. “Still, I’m glad to be here,” Hamell noted. “And I’m glad you’re here, too.” That night was Hamell’s first appearance at the Ballroom, which followed solid turnouts for earlier gigs in the Beachland Tavern (capacity: 148). Standing alongside the microphone, Hamell checked the tuning on his 1937 Gibson acoustic, and stepped back. “Now tomorrow, you’re going to be at work,” Hamell said, “and someone’s going to ask, ‘Hey, how was the Hamell on Trial show last night?’ And, at this point, I figure you’ll answer one of two ways. It might be, ‘Oh, despite the fact that only five of us showed up, Hamell wasn’t discouraged. He told new stories, sounded great, and played for like an hour and a half. It was awesome.’ Or, it might be, ‘Well, Hamell was pretty pissed off that there were only five of us there, so he didn’t say much, played Rush’s 2112 note for note, and left.’” He paused and smiled. “Don’t worry: it’ll be the former.” As he struck the opening notes of “John Lennon,” his right hand became a blur of slashing downstrokes at one hundred sixty beats per minute.

Hamell’s signature sound comes from his strumming with maximum aggression, tight to the bridge, which lends a metallic ring to a sustained and percussive low-end rumble. Hamell also plays slide guitar lines sweetly drenched with the timbre and phrasing of his musical forebears of the Mississippi Delta. “I’m a Libra,” he told me last fall, over coffee. “I need the balance.” Hamell hails from Syracuse, New York, and he sings and speaks in a decidedly Inland North baritone, with occasional bursts of endearing falsetto. His songs range from ballads of earnest devotion to punk bromides shot through with sympathetic snarl. The Philadelphia Weekly likens him to “Bill Hicks, Hunter S. Thompson, and Joe Strummer all rolled into one sweaty, snarling, pugnacious pitbull of a man”—a description unbecoming to pit bulls and Hamell alike. Instead, imagine Richard Pryor and Elvis Costello composing an unplugged album for Strummer, circa 1979. Now remove every perfectly coiffed hair from his head. Add forty years, forty pounds, and flashes of poignancy worthy of Carole King, and you’re close.

Night Guy at the Apocalypse: Scenes of a Rushing Midnight (2018), Hamell’s eleventh studio album, is steeped in American traditions, black and white, of humor and art, politics and transgression. Night Guy is discomfiting and funny, and one of the finest protest albums against the presidency of alleged billionaire Donald J. Trump. It’s also a compelling commentary on the opioid crisis.

Hamell Takes the Stand

Hamell on Trial at The Wild Buffalo, August 21, 2015, by Eric Frommer.

In 1989, Ed first took the stage as Hamell on Trial with his Gibson, a quickly receding hairline, and a deep, deep sense of righteous hilarity. In front of sparse crowds at the Halfmoon Café in Albany, and then the Electric Lounge in Austin, Hamell crafted his stage presence by running songs, lurid jokes, and heartbreaking stories up the flagpole, to see what would fly. He cut his first album for Blue Wave Records, his second for Doolittle Records, and shortly thereafter, he signed with Mercury Records. They repackaged the Doolittle L.P. as Big As Life (1995) to uniform acclaim: Billboard regarded the album as “a refreshing combination of electric fury and acoustic grace.” Following the comparably tepid reception for The Chord is Mightier Than the Sword (1997), Mercury dumped Hamell, it seems, for “making desperate to be nice”—a lyric from “No Delays,” the second track on Chord. At first, such a prospect seemed remote, given Hamell’s sweetly pugnacious demeanor, as well as his lone request for this essay. “Don’t make this a fluff piece,” Hamell told me. “Talk to my old managers. I’m unmanageable, you know.” When I revisit Chord, I hear in the arrangements and the production how Hamell was compliant to a fault: the emotional climax of “No Delays” contains a trio of post-Nevermind tropes: a grungy guitar lick yields to two seconds of Chris Cornell-y a cappella vocals before—surprise!—the band comes rushing back in. In his subsequent studio work, there’s nothing quite like it.

For Such-A-Punch Media, Hamell’s own label, his tally of albums includes Choochtown (1999) (recently reissued on pink vinyl and digital formats by New West Records), Ed’s Not Dead, Hamell Comes Alive (2002), and Yap (2003). Ed’s Not Dead finds Hamell in brilliant form opening for Ani DiFranco, and three albums followed on DiFranco’s Righteous Babe Records: Tough Love (2002), Songs for Parents Who Enjoy Drugs (2007), and The Terrorism of Everyday Life: Live From Edinburgh (2008).

Ahead of Songs, Hamell secured new management and a new career goal: the theater. “We were taken with his passion, authenticity, and play-until-he-bleeds ethic,” recalls Steven Saporta of the Invasion Group, a boutique management company. “Behind all that fierceness, there’s a gentle soul. And I was smitten by it.” With help from Lola Cohen of the Lee Strasberg Theatre and Film Institute, along with director Kate Valentine, Hamell developed a more rigorous presentation of his songs, stories, and off-color comedy and, onstage, he now stood either beneath a single spotlight or astride a single footlight. The Terrorism of Everyday Life debuted at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in 2007. Festivalgoers loved it, and Hamell received the Herald Angel Award. “We were really sittin’ on a high perch, and we tried to make [the show] happen in London,” Saporta tells me. “We couldn’t get arrested in New York.”

Saporta’s team figured that they could find a way to turn Hamell’s brilliance into something more sustainable than life on the house concert circuit. At Cohen’s urging, the Invasion staff encouraged him to screen test for character roles. Hamell obliged, but it never felt right. Soon thereafter, the Invasion Group and Hamell parted company. Not long after that, Hamell’s wife decided to part company, too. Their divorce devastated him, but he absolutely dotes on their son, Detroit, now seventeen, who has staffed the merchandise table—and told jokes between sets—on multiple summer tours. Hamell’s well aware, though, that his kid will be his own man soon. “I’m waiting for Detroit to say, ‘Well, I got a girlfriend, Dad, not this year.’ It’s going to break my fucking heart,” Hamell says. “But every year, it’s ‘Can’t wait, Dad! Can’t wait. Summer tour!’ Fingers crossed.”

After a six-year break from the studio, Hamell returned with The Happiest Man in the World (2014) and Tackle Box (2017). On tracks such as “Dance Till the Sobbing Stops” and “Better Believe It” (a dedication to Detroit), Hamell takes stock of his life and calls it good. “If a man’s wealth is determined by the amount of friends he has,” Hamell tells me, “then I’m a very, very rich one percent.”

Over the years, Hamell’s modest fan base has accumulated an all-star cast of D.I.Y. heroes. Hamell toured with M.C. Aesop Rock and collaborated with anti-folk hero Kimya Dawson. Aging fanboys include Henry Rollins and Robert Christgau, the dean of rock criticism, whose lowest grade for a Hamell L.P. is a B+. (With a cumulative GPA of 3.74 on a 4-point scale, Hamell has a shot at valedictorian.) And, rumor has it, you’ll find Hamell’s “Oughta Go Round” on the iPod of Bruce Springsteen. These accolades help buoy Hamell’s sense of humor, which owes a certain debt to his father.

Protest Humor and Protest Songs

In 1964, while the A.M. radio in the family’s Thunderbird played The Beatles’ “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” Hamell’s father shared a joke with Ed, age ten, about an electric-chair-bound prisoner and his final request from the warden. His father’s effort to upstage The Beatles proved inspiring:

I realized at that moment that rock’n’roll was more than just this incredible music … it was an attitude that [permeated] into other art forms, like film and literature. For me, a Charles Bukowski or a Hunter Thompson is infinitely more rock’n’roll than a Maroon 5 or Bon Jovi … For every John Lennon there was a Lenny Bruce. And for every Joe Strummer, there was a Richard Pryor … and for every Jack White, there was a Lewis Black.

For American comics, it’s a long-standing tradition: identify the symbolic boundaries of decency, step up to those boundaries, and leap with a Joe Strummer–like scissors kick right over them—with the hope that such transgressions might inspire their fellow Americans to produce a more perfect union. This conceit intermittently rears its head in rock and pop, and it served as inspiration for Robbie Robertson, guitarist and songwriter for The Band, to proclaim, “Music should never be harmless.”

This idea provides the organizing principle for Greil Marcus’s Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock’n’Roll Music (1975). In “Ancestors,” the book’s opening section, Marcus explores how the tension between the lowbrow humor of Harmonica Frank and the existential angst of Robert Johnson shaped the political stakes of American popular music.

They worked at the frontiers of the music, and they can give us an idea of what the country [can] give the music to work with—a sense of how far the music can go. Frank sang with a simple joy and a fool’s pride … [Johnson’s] songs deal with terrors and fears that few American artists have ever expressed so directly.

For Marcus, their descendants include Elvis Presley, The Band, Sly and the Family Stone, and Randy Newman—artists who “take more risks than most,” who “dramatize a sense of what it is to be an American [and] what the stakes of life in America might be.” The stakes of these dramatizations can get heady:

In an age when politics succeeds by confusing and obscuring matters of life and death, the strongest artists must claim those things as their own and act them out. Not many will ever have the nerve or the vision to do it.

Nearly twenty-five years after Big As Life, Hamell remains as engaged and as nervy as ever. On “Safe,” from Tackle Box (2017), Hamell offers comfort for listeners left dizzy by the contemporary obfuscation of life, death, and what it means to be an American.

If your soul is bouncin’ checks, you’ve lost all hope and face neglect,

if the water’s at your nose, and you’re on your tippy toes,

You—you’re safe here.

In 2018, Hamell kept sane by keeping busy, writing songs for F#(k Cancer: The Musical and touring overseas. Shadowbox Live, in Columbus, Ohio, invited Hamell to put together the songbook for a play written by Jimmy Mak shortly after Shadowbox founder Stev Guyer was diagnosed with brain and thyroid cancer. While writing the play, Mak sent character sketches to Hamell, and Hamell replied with songs—thirteen of which made it to the stage. “Sometimes the song didn’t fit at all,” Mak notes, “but the song was so great and so true I’d write around the song.” Hamell also toured the UK, France, Iceland, and Ireland. In Ireland, Hamell tells me, “If sixty people come out they could be as young as sixteen and as old as seventy-five and they don’t have that puritanical sense like in the United States. I don’t get that in Ireland. Ever. At all. From anybody. So there’s a little twinkle in their eye and they understand the angel and the devil of human nature.”

Stateside, Hamell still plays the club circuit and house parties, and his opportunity for sub-stardom may, alas, reside somewhere in his rearview mirror. Still, his work abides by Marcus’s key edicts for artists in rock and roll:

There have been great artists who have worked beyond the public’s ability to understand them easily … [and hoped] that their work would lift America to heaven, or drive a stake in its heart. This is a democratic desire … to discover what it is that diverse people can authentically share. It is a desire of the artist to remake America on his or her own terms.

The presidency of George W. Bush sharpened Hamell’s understanding of those stakes, and he constructed a variety of personae to channel these desires on Tough Love (2002).

On “Don’t Kill,” the album’s opening track, Hamell plays the role of God himself. Like Newman’s Lord in “God’s Song,” Hamell’s depiction of the Father is more Old Testament than New, but his Lord is disgusted rather than amused, and maintains a sliver of faith in the human capacity for redemption.

Was it the “Thou” part that threw you? Thou means “you.”

Was it the “Shalt not” part that bamboozled you? Shalt not means “don’t.”

There are no divinely sanctioned murders. Who’d know better than me?

I’m God, how come you don’t hear me?

I’ve been saying the same shit for centuries.

On the soft-spoken “Hail,” Hamell eavesdrops in heaven on a group of friends who, on Earth, paid dearly for their audacity to live openly and honestly. Brandon Teena was murdered, at age twenty-one, in Humboldt, Nebraska, in 1993, for their gender ambiguity. Brian Deneke was murdered, at age nineteen, in Amarillo, Texas, in 1997, for his punk couture. Matthew Shepard was murdered, at age twenty-one, in Laramie, Wyoming, in 1998, for being gay. Hamell sings softly, pensively, about how only in heaven can his protagonists “be who we want to be”—a sentiment long attested to be fundamentally American.

On Songs for Parents Who Enjoy Drugs (2006), angels and devils get equal billing. When George W. and his enablers went low, Hamell went lower. On “Values,” Hamell imagines Detroit, at age two, applying the White House’s rules of engagement on the playground:

He said, “I’m an isolationist, Dad. That kid made me really fuckin’ mad.

“I don’t need him or NATO, God chose me. It’s fate.”

Oh, values are tough to teach a child

When the president has gone completely wild.

Like his idols Hicks, Johnny Cash, and Pussy Riot, Hamell carries the burden of speaking inconvenient truths to the masters of war.

When I ask Hamell about his marrow-deep desire for justice, he replies, “I don’t know,” and pauses. “I don’t know! I don’t know! I don’t know.” He pauses again. “Do we really need religion to tell us what’s right or what’s wrong?” Eventually, Hamell settles on the importance of honesty. “I see these politicians—they say, ‘Oh my favorite book is the Bible.’ You’re full of shit. I don’t think that you read the fucking Bible,” Hamell says, with playful agitation. He then compares such sycophants to the clientele at a downscale establishment in Syracuse—“Cheers had Sam. We had Son of Sam”—where he tended bar. “They would say, ‘Well, I’m a thief,’ or, ‘I’m a drug addict.’ I respected that honesty.”

Hamell’s social circle in Syracuse dominates Night Guy, and the depictions of their drinking, snorting, and consorting recall another album about breaking hearts (and noses) on a Saturday night: Tom Waits’s The Heart of Saturday Night.

Musical Scores for Political Mayhem

In mid-April 1974, when Tom Waits recorded the first tracks of The Heart of Saturday Night, special prosecutor Leon Jaworski issued subpoenas for the “White House tapes” of President Richard Nixon. On May 14, when Waits returned to the recording studio, impeachment hearings were underway for President Nixon. Upon the release of Night Guy, in October 2018, the team of special counsel Robert Mueller entered the seventeenth month of an investigation that, as late as May 2019, seemed likely to serve as the prelude to impeachment hearings for President Trump. The coincidence of constitutional crises aside, other qualities bind Saturday Night and The Night Guy. On the album cover of Saturday Night (a homage to the L.P. cover of Frank Sinatra’s Wee Small Hours), Waits stands outside a bar, smoking a cigarette, while a woman sizes him up as a potential client. On the album cover of Night Guy, Hamell tends bar at the establishment known as the Apocalypse, pointing a gun at someone outside the frame, and a woman between tricks stands to his left. The songs on both albums work as loosely tied vignettes, and they register Waits’s and Hamell’s affections for characters who might have wandered free from tales by Charles Bukowski or Raymond Carver.

Yet the albums work in vastly different registers. With jazzy syncopation, Waits portrays neon-lit characters of Los Angeles wrapped in rayon and chiffon, driving massive American sedans, flush with Eros and alcohol, discarding inhibitions and Sansabelt slacks and disappearing by the dawn’s golden light. Hamell portrays characters at a dive bar in Syracuse in the mid-Eighties, clad in leather, denim, and spandex, carrying knives, shivs, and sniper rifles. They’re hopped up on Thanatos and speed, alit with Jack Daniel’s and toxic masculinity. They settle scores with corrupt authorities, dump the bodies, and sidle back to the bar. Or they disappear. The Night Guy sees it all.

Waits played piano and guitar on his album and, in the slick, final mix, is joined by a rhythm section, clarinet, saxophone, and strings. Hamell recorded the album on his iPhone, mostly on the road, and it includes little more than voice, guitar, and percussion. Listen for the ambient buzz of diesel trucks on “Rollin’ with Icarus”: Hamell recorded the track late one night, in his car, at a Michigan truck stop. In the final mix, Hamell leaves the rough edges visible, which mostly works, except when it doesn’t. On select tracks, Hamell’s phrasing falls short of his usual precision, and abrupt splices at track endings betray his usual diligence, rather than impress as authentically punk.

Night Guy offers a touching, if critical, tribute to Hamell’s friends from back in the day. When I ask about the inspiration for “Rollin’ with Icarus,” an account of the killing of a dishonorable deadbeat, he confirms it’s fact and fiction. “Being in the car, high, with a bunch of screwballs,” Hamell says, “and the next thing I know, they’re robbin’ some fuckin’ place and I’m the lookout guy—that part is true.”

On “Toast,” we find the Night Guy in a wistful, boozy frame of mind:

I drink tonight to Trudy, from Paris to Denmark,

who never knew her sister, and followed in the dark,

Whose breasts rose and fell like finance, like laughter, like song.

Who never had a conscience so never could be wrong.

Trudy’s characterization via metaphor proves distinctive on this album. On previous albums, on dozens of songs, Hamell wrested telling metaphors from the tension of the angst and the humor of his forebears. On “John Lennon,” a twitchy, shout-laden, spoken-word number about an early Yoko Ono exhibition, a young Hamell is “carried on a path, straight as a bullet, closer, closer, closer, closer, closer until my chest slammed into Lennon’s.” On the reverb-laden “Mouthy B,” Hamell admires a lover from Australia and her expressions of boredom with the U.S.A.:

“And what’s with all the flags?

“I’ve never seen such insecurity in all my life.

“L-i-i-i-i-f-e,” she would say, dragging the vowel like a thief wrestling

a weighty bag of golden chalices down the Vatican steps.

But that’s not the case on Night Guy. Hamell renders the other characters with light brushstrokes in stark, realist detail, as if he were copping descriptions from a police blotter.

“That’ll Be the Bloody Day,” recorded live with English patrons on background vocals, marks the return of Bobby, the craziest of lovable antiheroes in the Hamell oeuvre. Here, he’s on the run for betraying the honor among thieves. The significance of honor for Apocalypse regulars gets reprised in “Bar Fight,” another ballad with just guitar and vocals.

… and the ambulance arrives and we clear a path.

They ask for insurance and the whole bar laughs …

We meet at night, the events relayed,

and it sure beats working at the end of the day.

Work may lack meaning, but vigilante justice delivers the savory rush of dopamine. Characters at the Apocalypse may break each other’s noses, but their social bonds provide a buffer of solidarity against isolation.

Across the country, the hospitality of Hamell’s fans makes possible his D.I.Y. ethic: they host house concerts and provide him (and Detroit) with rooms for the night and breakfast in the morning. Hamell forms enduring bonds with his hosts, and these intimate contacts serve as booster shots against our contemporary epidemic of loneliness. “The opposite of addiction is not sobriety,” argues journalist Johann Hari. “It is human connection.”

In select grooves on Night Guy, I hear echoes of the victims of the opioid epidemic, the contemporary counterparts to the bar flies of the Apocalypse. I hear them collapse against floorboards in strange hallways, knocked out loaded, hollow-eyed, alone. I hear the rattle of OxyContin capsules in bathroom drawers in postwar bungalows in Ohio’s Miami Valley. I hear the sirens of first responders, on the same streets, day after day, administering Naloxone to residents of communities decimated initially by deindustrialization. And I hear the death rattle of the thousands, young and old—so many, so young—that first responders could not save.

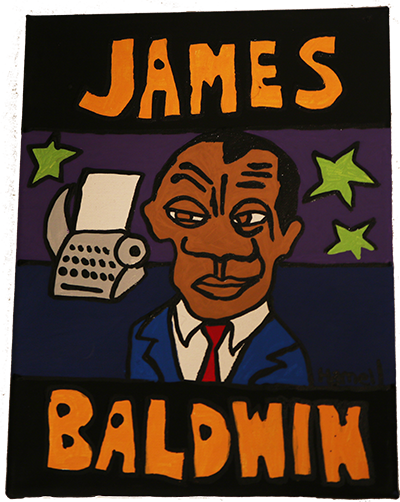

Hamell’s portrait of James Baldwin.

Bodies and f-bombs alike pile up on Night Guy, and Hamell offers the following rationale for his scabrous vocabulary. “If I’m going to use a word like ‘oxymoronic,’” Hamell explains, “I want to make sure I don’t come off like Bono or something, so I’ll throw a ‘fuck’ in front of it, to let them know that I got one foot in the trenches as I aspire to the stars.” This explanation doesn’t quite account for his other fifty-two f-bombs that peppered our conversation.

Like Hamell, even my friends who speak in paragraphs dropped a hell of a lot more f-bombs in 2018 than they did in 2016. It’s a sign of the times. When words do fail him, Hamell paints original compositions and portraits of his heroes, including Amy Winehouse, Jack Kerouac, and James Baldwin. “I don’t think I’m a great painter. But people for some reason gravitate towards it,” Hamell says. “Maybe it’s the colors I use, the boldness of it.” It’s more than that. It’s about the visible trace of Hamell’s labor, the aura embodied in a craft-produced object: it’s the scarcest feature available in an industry sustained by petabytes of zeroes and ones. On display at home or the office, these paintings prompt conversations about taste, taboos, and what we the people can authentically share.

On May 9, 1974, the House Judiciary Committee convened impeachment hearings for Nixon, and Jon Landau of The Real Paper attended a Bonnie Raitt concert. The opening act, Bruce Springsteen, inspired Landau to pen words that inspired rock journalists for decades to come: “I saw rock and roll past flash before my eyes. I saw something else: I saw rock and roll’s future and its name is Bruce Springsteen.” Rock journalists love this moment and the critical and commercial success that followed for Springsteen, as if Landau’s words helped chart a more glorious path of musical history.

Let me set aside my disbelief in this prospect and, for the sake of American democracy, channel my inner Landau: I have seen the future of rock and roll, and it’s a potty-mouthed senior citizen, wielding an eighty-two-year-old guitar, making a devilish racket as big as life, appealing to the better angels of our nature.