On a chilly and overcast Saturday in March, I parked my rental car at the base of the hill at Wounded Knee. The week before, historic blizzards and gusts up to seventy miles per hour had piled snowbanks atop soil frozen as solid as concrete. In some places along the highway, snowpack stood taller than the vehicles motoring past. When the snow melted under the torrential rains of a bomb cyclone, the creeks that nourish Pine Ridge overflowed their banks. Climate change, which shifts jet streams and leads to greater ocean evaporation and Midwest precipitation, makes biblical storms like this more likely on the arid plains. Flooded and mucky back roads cut families off from medicine, food, water, and outside assistance. Water lines broke all over the reservation. An official advisory from the tribe warned of “fecal contamination or other disease-causing organisms” in tap water, directing residents to boil their water for three minutes before use. The New York Times reported eight thousand without potable water. On a reservation that routinely tops the list of the poorest places in the country, and that one study likened to a post-disaster landscape, the deluge turned systemic injustices into death sentences. The Times reported at least three fatalities as a result of the catastrophe. South Dakota and the tribe declared a state of emergency.

On Big Foot Trail, a highway at the foot of Wounded Knee’s hill, residents of the Wounded Knee Houses, whose water main was broken during the flood, passed me on a pilgrimage to a nearby post office, where they queued up to collect rations from the National Guard. Earlier that day, Governor Kristi Noem had rolled onto the reservation, right past my rental car, with a convoy of Humvees loaded with tanks of water. The governor’s official Twitter account posted images of the state’s top executive filling water jugs, chatting with soldiers, and listening to tribal members. But many on the reservation felt her concerns to be insincere and the photo ops opportunistic. Two weeks earlier, Noem had rushed to pass a bill that would penalize protesters—or what the state called “riot boosters”—for opposing projects like TransCanada’s Keystone XL pipeline, if they participated in or were even tangentially connected to a “violent” protest. Many tribes, like the Oglala, oppose the project and say Noem’s legislation violates the First Amendment; the American Civil Liberties Union sued the state, arguing that the law is unconstitutional. “We are particularly offended that you consulted TransCanada before introducing these bills but failed to consult the Oglala Sioux Tribe, or any of the sovereign bands of the Sioux Nation, though our treaty lands would be traversed and endangered by the Keystone XL Pipeline,” Oglala tribal chairman Julian Bear Runner wrote in a letter to the governor. Flooding, broken pipes, and widespread suffering caused by the disaster only seemed to vindicate Bear Runner and his tribe. (Months later, following a legal injunction, Noem and the state attorney general filed a settlement agreement with the plaintiffs, nullifying most of the legislation.)

As I took in the scene, Jarret Jealous, a friendly middle-aged father, approached offering his wares: handmade dream catchers, carved antler key chains, and buttons fashioned from elk bone. I turned down his pitch, so he took another tack, volunteering information about the monument and the best way to march up the muddy hill. As Jarret talked, a man named Cody, Cody’s girlfriend, and a pup they’d found on the side of the road—all residents of Wounded Knee tribal housing—came up to ask if I had any water. I gave them one of the big bottles stashed in my back seat. Then, a ten-year-old named Raymond Eagle Hawk, also a Wounded Knee resident, stopped and offered me a story. He spoke of Lost Bird, an infant who miraculously survived the massacre and blizzard in 1890—some say she was one of two infants found beneath their mothers’ frozen bodies that day. Adopted by the abusive General Leonard Colby, Lost Bird lived an impoverished and ill-fated life. She contracted syphilis and died, likely of influenza, at 29. When he finished, Eagle Hawk asked if I could spare ten dollars for his trouble. Shocked by the bluntness and brutality of the adolescent’s tale, I obliged.

And then I trudged up the hill, the mud sucking at the heels of my Ariat ropers. At the top, about seventy-five feet long and fifteen feet wide, bordered by a thin slab of concrete and surrounded by a chain-link fence, there is a mass grave that holds the remains of 146 Lakota people. Outside of the fence is a humble monument, erected by descendants of the slain in 1903, that’s inscribed with the names of 43 victims. “Many innocent women and children who knew no wrong died here,” reads a fading epitaph cut into stone.

This was my first visit to Wounded Knee—a place that, as a young Native man and writer, I had heard and read so much about. Notepad and pen in hand, I was determined to find meaning here. My pilgrimage, I hoped, might reveal some higher purpose hidden within our seemingly endless Indian losses. When I reached the burial site, I removed my Chicago Bulls cap to show respect. I saw that other visitors had tied tobacco offerings in small cloth pouches to the fence to honor and carry forward the spirit of the martyrs. I had no tobacco to offer—just time and prayers.

On December 29, 1890, the Seventh Cavalry of the United States Army gunned down mostly unarmed men, women, and children who had been traveling from the Cheyenne River reservation under the leadership of Chief Big Foot and were camped in the ravine below this hill. “The smoke was so dense,” said White Lance, a survivor, “I couldn’t see anything.” Their shooting was so reckless that some American soldiers accidentally killed their brothers in arms. After the first mass murder of Lakota in their camp, soldiers chased fleeing survivors across the prairie for hours, executing them at close range. They left the bodies littered across the plain. Two days later, a blizzard rolled in. Then, the Army hired civilians to collect the frozen corpses, buried in snow, paying $2 for each Indian interred on the hill. For actions at Wounded Knee, the Army awarded twenty soldiers the Medal of Honor, its highest commendation for war heroes. Their citations praised “distinguished gallantry,” “extraordinary gallantry,” “bravery in action,” “distinguished bravery,” and “conspicuous bravery.” That same year, the U.S. Census Division announced the close of the frontier, a demographic boundary beyond which the population was less than two per square mile. Settlers had spread from sea to shining sea. The Indigenous, it was believed, would soon go extinct.

In life, many of the Army’s victims were the followers of the Ghost Dance, a nineteenth-century faith that originated with a vision, delivered, it was said, by God to the Paiute messiah Jack Wilson, more commonly known as Wovoka. The dance, an all-night ceremony where worshippers held hands and shuffled clockwise in a circle to spiritual songs, was believed to hasten the renewal of the world, the return of the ancestors, and maybe even the departure of the colonists. Ghost Dancers donned shirts painted with the sun, the stars, and the moon—celestial images connecting the wearer to the heavens. These shirts made them bulletproof, according to some Lakota practitioners. Among the Indigenous, the Ghost Dance inspired resilience and revival in the face of devastating loss and upheaval. Among some settlers and military officials, notably in South Dakota, the dance fomented fear of an Indian insurgency.

Generations later, on the night of February 27, 1973, that fear was realized when fifty-four cars loaded up with Oglala and American Indian Movement (AIM) activists descended on Wounded Knee to reclaim and liberate this hallowed ground. AIM joined already strong local opposition to Pine Ridge tribal chairman Dick Wilson, who had recently weathered an impeachment trial on corruption charges. Reportedly armed with weapons including hunting rifles, rusting .22s, plastic M16s, carved wooden rifles, and a single AK-47 smuggled back from the jungles of Vietnam, AIM wasn’t much of a fighting force, and the hill was a tactical disaster to defend. But that wasn’t the point. This was Wild West political theater. Following the lead of local activists, AIM declared Wounded Knee the Independent Oglala Nation and delivered a list of demands to the Justice Department: hold Senate hearings on broken treaties, investigate the Bureau of Indian Affairs, uproot corruption on South Dakota reservations, and send a White House representative to negotiate. If the Nixon Administration failed to meet these demands, AIM warned, the occupiers, like their Native ancestors, were willing to die for their cause.

From the outset, the occupation presented a public relations crisis for the administration: negotiate with armed radicals, or risk a deadly firefight at the site of the most infamous massacre in American history. And this time, the public was on the Indians’ side: a Harris Poll released that April found that 93 percent of Americans had been following the occupation and that 51 percent were more sympathetic to the occupiers than to the federal government. AIM’s audacious actions, meanwhile, energized Indian Country: Navajos marched in Phoenix; Tuscaroras smashed windows in Lumberton, North Carolina; Passamaquoddys burned tires on the sides of highways in Maine; and students at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, hopped in their cars and took off for Pine Ridge.

Three weeks after capturing Wounded Knee, Leonard Crow Dog, an Oglala holy man, led a Ghost Dance in the same gully where Big Foot’s band had been gunned down. Wearing ceremonial shirts cut from scraps of canvas and painted with Wovoka’s symbology, forty men and women, including AIM leader and Oglala tribal member Russell Means, danced for four days. “The white man says that the 1890 massacre was the end of the wars with the Indian, that it was the end of the Indian, the end of the Ghost Dance,” Means said at a community meeting after the ceremony. “Yet here we are at war. We’re still Indians, and we’re Ghost Dancing again. And the spirits of Big Foot and his people are all around us.”

However, the risk inherent in AIM’s war games eventually caught up with them. After the killings of Frank Clearwater, who had come from North Carolina to support, and Buddy Lamont, an Oglala tribal member, both shot in firefights with authorities, tribal leaders called for an end to the occupation after seventy-one days. The federal government spent the next few years prosecuting AIM members, and the organization descended into dysfunction.

I paced the cemetery once liberated by AIM clockwise like the Ghost Dancers, searching these hallowed grounds and my thoughts, believing the life of Big Foot and the vision of Wovoka held buried truth and unrealized promise. I spent the better part of an hour atop that hill, but I found no revelation. Instead, I gained a new vantage point from which to observe the disaster and exodus unfolding below me. From a distance, I watched the residents of this somber place lumber up and down the highway beneath a gray sky, walking to the post office empty-handed and returning with jugs of water. Here on the hill: the victims of genocide. Down below: the survivors. Here: the final apocalypse of the American frontier. There: the carnage of climate change. One cataclysm hatched atop another. Wovoka’s vision, inverted.

Maybe this is our lot as Indians, I thought. The idea and the scene from which it sprang felt so hideous that they should be forgotten and hidden—perhaps on some far-off reservation, just like this and just like us.

I descended the hill. Back on Big Foot Trail, I handed twenty dollars to Jealous, and another twenty to two elderly Native women, Deborah and Granny Red Feather, who were smoking in their parked car. It was my modest offering to the Lakota and this place.

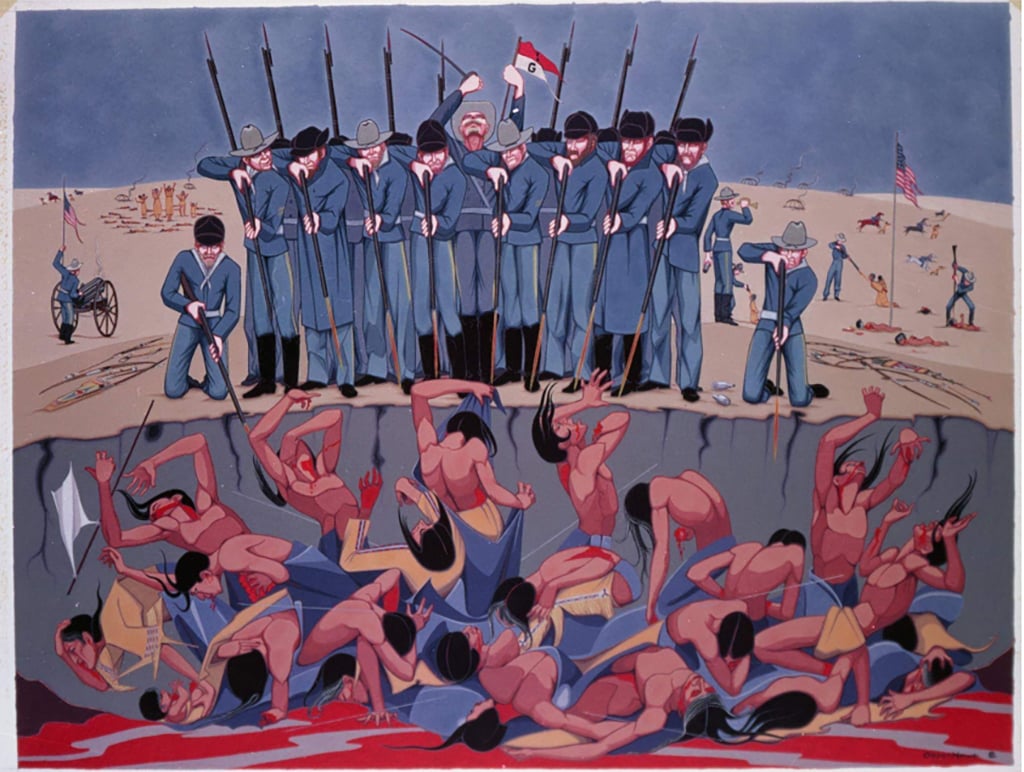

Wounded Knee Massacre, a painting by Oscar Howe, 1960.

Journalists and Hollywood types often jet into Pine Ridge from the coasts to extract tales of reservation poverty. When they do come, their fixer is often the thirty-year-old Oglala filmmaker and photographer Willi White. He wanted me to see Pine Ridge through his eyes, so the next day, a Sunday, he took me on a driving tour of the reservation, a landmass larger than the state of Delaware and home to about twenty thousand. In his Ford sedan we zipped through flooded communities with colorful names, like Red Shirt Table, Thunder Valley, and Sharps Corner, following thoroughfares threaded between windswept badlands and wide-open ranch lands. White kept the radio tuned to KILI 90.1 FM, a Lakota station. Public safety announcements punctuated powwow songs by local drum groups like Bad Nation and the Porcupine Singers. Near overflowing creeks and rivers, we motored past men stacking sandbags. Occasionally, we’d come upon a stray dog, mustang, or hitchhiker, or a roadside memorial to a young person who had lost their life to drunk driving. As he drove, White narrated histories both distant and personal—his inheritance of the scattershot aftermath of Wounded Knee.

Passing boarded-up tribal housing on Highway 18, the same road those committed AIM activists had once motored down, he talked about the meth epidemic on the reservation. Chemicals used to cook the drug contaminate kitchens that the tribe doesn’t have the resources to clean up. Addiction, meanwhile, is taking lives. White shared the story of his cousin, a twenty-one-year-old who was using and selling. One day, she was stopped by the cops and, while detained in a jail cell, swallowed all the meth in her possession, and died of an overdose.

In Whiteclay, a reservation border town just across the state line in Nebraska, White pointed out some of the old haunts of the so-called “Skid Row of the Plains.” Whiteclay used to sell more than four million cans of beer a year to residents of Pine Ridge, where liquor is illegal. In 2017, after decades of protests and lawsuits, the Nebraska Liquor Control Commission voted to revoke licenses to sell beer in Whiteclay. Though the closest watering hole is closed down, alcoholism persists across the reservation, where bootleg beer reportedly sells for $3 a can and bottles filled with a cocktail of vodka, hand sanitizer, and water sell for about $10. Some, like White, are starting to question the effectiveness of prohibition.

Then White drove me through the community of Oglala, where some residents live in Federal Emergency Management Agency trailers, holes blown through their windows and siding by hail a few years back patched with plywood. He pointed to the high school where his dad became known as “The Legend” on the hardwood—one of the reasons White picked up a camera and not a basketball. He took me to the Red Cloud Indian School, his alma mater, which, according to the school’s website, has graduated more Gates Millennium Scholars than any other school in the nation. It was at Red Cloud, named after perhaps the greatest Lakota statesman of the nineteenth century, that White learned how to make films. “I fell in love with how it made me feel,” he told me.

White’s filmmaking initially helped him escape the weight of Wounded Knee’s histories—his first film was a short about New Zealand, inspired by his love of Lord of the Rings, that was shot on his father’s hunting camera. But if stories and films offer creative and intellectual freedom, the heavy histories, places, and experiences from which they spring also inspire him and keep him grounded here, rather than setting out for Los Angeles or Brooklyn. White wants one of his future projects to be about the dueling legacies of Wounded Knee—the massacre and the liberation. He hopes to focus on the lesser-known aspects of these struggles, and at Red Cloud, he has access to archival photos of memorializations of the carnage as well as images of some ceremonies held here over generations. He also intends to put the lives of the women in AIM, like Madonna Thunder Hawk, who are often overlooked in favor of men, at the center of the narrative.

On Sunday, as we ascended the hill at Wounded Knee, White told me about his relative Swift Bird, who was killed and buried alongside Big Foot and the Ghost Dancers. At the top of the hill, we happened to run into Jeff Moreno, the son of American Indian Movement (AIM) leader Dennis Banks, who helped lead the takeover. “We were the prophets, the messengers, the fire-starters,” Banks wrote in his autobiography, Ojibwa Warrior, cowritten with Richard Erdoes. “Out of AIM came a new breed of writers, poets, artists, actors, and filmmakers.”

“We figured we’d come here and pay our respects,” Moreno said, accompanied by his wife Melinda and daughter Jordilyn, whose hair was tied in pigtails.

After Moreno departed, White and I spent a few minutes there, surveying the ground, still searching for meaning.

“It gets me really reflective—just the different things that our people have been through,” White said. “I’m constantly reminded about things like this, events like this, that really shaped our history, shaped our communities, and how that’s evolved into some of the challenges that we face today.”

Wounded Knee holds both the bloody abyss and the unconquered vision of this continent’s First Peoples. It is the site of a massacre and of the Independent Oglala Nation. Both stories are ours equally: genocide and its aftershocks in the climate; the Ghost Dance, the American Indian Movement, and the campaign against the Keystone XL pipeline. Some days, I feel we have been condemned to the most wretched fate of any people—a slow, painful, and intergenerational death. But then, I see our people rising. And sometimes I see both at once, in the same frame, and in the same place. As the climate breaks down, we remain caught between both legacies of Wounded Knee—genocide and freedom—the horror of the massacre and the dream of the massacred.