Compared with Nuremberg’s magnificent Palace of Justice, a Renaissance-revival showpiece where American prosecutors tried Nazi war criminals after World War II, the Expeditionary Legal Complex (ELC) at Guantánamo Bay provides little to please the eye. Enclosing the facility, which houses Gitmo’s military courtroom, is a ten-foot chain-link fence covered with dark-green sniper netting and two dense coils of razor wire. Unseen soldiers keep watch from mobile guard towers. Around the fence runs a security perimeter made of bright-orange Jersey barriers, seemingly the work of a counterterrorism specialist strongly influenced by Christo and Jeanne-Claude. Photographing the complex is strictly forbidden, except from one specific point marked by a 3’×3′ spray-painted square on a walkway, though my attempt to use this square is interrupted by two soldiers puttering by in a golf-cart-like vehicle called a mule, who bark at me until my escort, an unflappable Marine sergeant from the Division of Public Affairs, politely informs them of the picture-taking rule. Sheepish, they drive off. My sergeant dutifully examines my photo to make sure my lens hasn’t strayed; asked to account for such precautions, he answers in a deadpan, “So Al Qaeda doesn’t know where to go when they land with their submarines.”

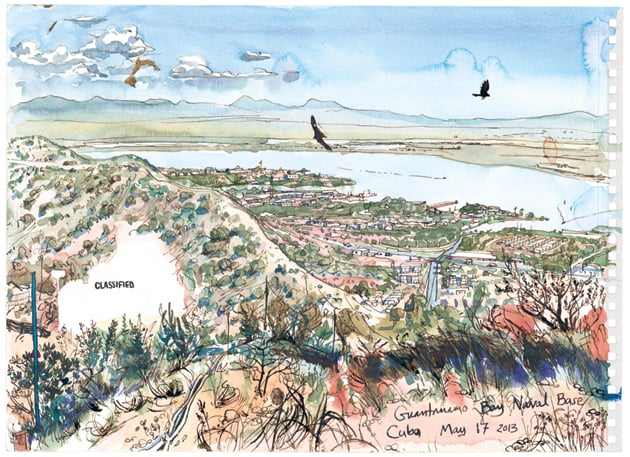

Artwork © Steven Mumford, who traveled to Guantánamo Bay in February and May of 2013 to make the drawings accompanying Lawrence Douglas’s report. Mumford’s depictions of the pretrial hearings (cover and above) were cleared for publication by the security court officer.

The courthouse building, which can be glimpsed only from inside the fenced complex, looks like a Costco, a windowless aluminum structure colored Naples yellow with a pitched roof. This is where the trial of Abd al-Nashiri, the senior Al Qaeda lieutenant alleged to have masterminded the bombing of the U.S.S. Cole in Yemen in 2000, will presumably begin sometime next year. Now wending its way through pretrial hearings, the Nashiri case is one of two presently before the commissions; the 9/11 case against Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM) and four co-defendants is also slowly heading toward trial. These cases, involving the only capital charges to result from Al Qaeda crimes, are not only the most important to be submitted to the military commissions but also the most significant to come before a military court since high functionaries of the Third Reich stood trial in occupied Germany. In his opening address at Nuremberg, Robert Jackson, who had taken a leave from his position on the Supreme Court to work for the Allied prosecution, put the task facing the tribunal poetically: “To pass these defendants a poisoned chalice is to put it to our own lips as well.” Jackson understood that law itself stood on trial at Nuremberg; the unusual tribunal had to demonstrate that it was something other than, as one prominent critic put it, a “high-grade lynching party.”

There are similar stakes here at Gitmo, and serving as a less literary reminder of them is a stuffed animal belonging to Richard Kammen, the civilian lawyer who heads Nashiri’s defense team. Gray with pink ears, it stands about six inches tall. A court security officer first mistook the animal for a bunny, a touch of cute ornamenting the defense’s table. But the MP should have looked more closely, for rare indeed is the bunny that carries a joey in a pouch. He might also have noticed a second kangaroo, a small gold one, glimmering in the spot on Kammen’s lapel where one has grown accustomed in such settings to seeing an American flag. As Kammen, an accomplished lawyer with four decades of trial experience, notes, his choice of lapel pin “is not meant to express my love of Australian wildlife.”

History has more than vindicated Nuremberg; how it will treat the Guantánamo military commissions is another matter. But a defense lawyer’s props hardly settle the issue. My own impressions of the happenings in the ELC courtroom suggest that Kammen’s kangaroos should be seen less as the final word on the military commissions than as a reminder of the extraordinary challenge they face: to demonstrate that a tribunal born of an impatient contempt for due process can prove itself a legitimate institution of American law.

On the morning of October 12, 2000, the U.S.S. Cole, a Navy destroyer with a crew of around 300, arrived in Yemen’s Port of Aden to refuel. Shortly before noon, a fiberglass motorboat operated by two suicide bombers and laden with several hundred pounds of explosives blew a forty-foot-wide hole in the ship’s hull, killing seventeen crew members and injuring dozens more. “The people of Yemen partied on shore the night we were attacked,” Joe Pelly, a now retired senior chief petty officer who was onboard, told me. With Yemeni president Ali Abdullah Saleh publicly blaming the bombing on the Mossad and parliamentarians railing for jihad against America, an FBI team sent to Aden confronted what one agent described as “the most hostile environment the FBI has ever operated in.” Nevertheless, the team broke the case. The alleged chief architect of the attack was identified as a Saudi of Yemeni descent named Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri. According to American intelligence reports, Nashiri had fought with the Taliban against the Northern Alliance before joining Al Qaeda sometime around 1998. He soon emerged as one of Osama bin Laden’s most valued associates, allegedly becoming the head of Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. Evidence indicated that Nashiri had prepared an earlier strike against another Navy destroyer, the U.S.S. The Sullivans, but that a skiff filled with explosives had gotten stuck at low tide and become swamped under its excess weight. Later investigations also linked Nashiri to an attack on a French tanker that killed one crew member and caused tens of thousands of gallons of oil to spill into the Gulf of Aden.

American operatives captured Nashiri in Dubai in October 2002. For nearly four years after that, his whereabouts were unknown. Former U.S. intelligence officials later indicated that Nashiri was first held in Afghanistan, in a secret CIA location called the Salt Pit, then flown to a CIA black-site prison in Thailand; from there, he was ferried to another CIA prison, in Poland (his suit against the Polish government remains before the European Court of Human Rights); next he was rendered to Morocco, then to Romania (he has also filed suit against the Romanian government). Not until September 2006 was Nashiri transferred, along with thirteen other “high-value detainees,” to stand trial before a military commission at Guantánamo Bay.

Trial by military commission has played a long, if less than continuous, role in American legal history. As early as 1780, George Washington convened a board of senior officers to weigh charges of espionage against the British army major John André, later executed by order of the commanding general. The tribunals established by General Winfield Scott during the Mexican-American War firmly established military commissions by name. Commissions were used extensively during the American Civil War, and President Andrew Johnson convened one to try the conspirators in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. After World War II, the United States used military commissions to try not only Nazis but also German spies and saboteurs on American soil and Japanese war criminals in Tokyo.

Despite these precedents, George W. Bush’s decision, announced in a short executive order on November 13, 2001, to try “Certain Non-Citizens in the War Against Terrorism” before military commissions represented a dramatic break from practice. Historically, military commissions had been used in a narrow range of cases — when, say, martial law had been declared or the crimes in question were incident to acts on the battlefield, where civilian courts could not practically be convened. But Bush’s “global war on terror” made the very term “battlefield” something of a misnomer. More to the point, his order came at a time when federal civilian courts (also known, by virtue of the Constitution’s enabling language, as Article III courts) were fully functioning. These courts had established an impressive, though not unblemished, record of trying and convicting terrorism suspects — from homegrown insurgents such as Timothy McVeigh to the “blind sheikh” Omar Abdel-Rahman, sentenced to life imprisonment in connection with the 1993 World Trade Center bombing. Critics, however, argued that civilian courts, with their indulgent procedures, grandstanding defense attorneys, lax treatment of sensitive intelligence, unreliable juries, and endless appeals, were ill equipped to deal with terrorism cases.

These concerns had some merit, and yet the Bush Administration’s conclusion that “the nature of international terrorism” made it “not practicable to apply . . . the principles of law and the rules of evidence generally recognized” in criminal cases came not from the law-enforcement or intelligence communities, which largely kept their faith in the federal court system, but from officials within the political branches — in particular, from Vice President Cheney and his legal counsel, David Addington, who believed the threat posed by Al Qaeda required a new legal paradigm that permitted, in the words of one Pentagon official, taking “the gloves off.”

Rather than work from existing models, Bush, Cheney, and Addington sought to radically reshape the structure, method, and purposes of trials undertaken in the name of this nebulous global war. Norms designed to protect the dignitary rights of the accused and processes designed to instill confidence in the fairness of verdicts could all be jettisoned as “not practicable” in cases involving alien terrorism suspects. Suspects could be denied access to the evidence against them. Confessions extracted through coercion or torture could be used to incriminate. Verdicts would be final, with dramatically curtailed forms of appellate review. In contrast with the lumbering work of trying cases before civilian juries, trial by military commission would hum along at a clip.

In practice, Bush’s experiment with military commissions produced a record of unseemly missteps that frustrated the cause of justice and damaged America’s standing abroad. Basic questions of procedure led to rancorous debates among commission members. Prosecutors labored aimlessly without adequate leadership, institutional support, or legal tools, stymied by the CIA’s steadfast refusal to share evidence and disillusioned by the realization that virtually all cases were tainted by allegations of detainee abuse or torture. With its 2006 decision in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, the Supreme Court brought down the entire shoddy edifice, declaring Bush’s military commissions in violation of both the Uniform Code of Military Justice and the Geneva Conventions (and leading Donald Rumsfeld to quip, “So I’m going to go down in history as the only Secretary of Defense to have lost a case against a terrorist?”).

Barack Obama assumed the presidency with a commitment to reform Bush’s tribunal, if not abolish it altogether. The Military Commissions Act of 2009 built on an earlier effort by Congress, in 2006, to transform Bush’s scheme into a workable instrument of American justice. But when it came to deciding what to do with the 9/11 defendants, the new administration waffled badly. First it announced, on the eighth anniversary of Bush’s executive order, what many jurists had urged from the outset: it would bring KSM and his confederates to federal court to stand trial. Then, in the face of opposition from both congressional Republicans and New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg, who openly fretted about the security nightmare posed by shuttling KSM to Lower Manhattan, Obama reversed course. The 9/11 case would stay in Gitmo.

The argument over where to try KSM turned into a referendum on the military commissions. Both sides in this debate appeared to overlook the fact that administration lawyers had never considered transferring the Cole case to civilian court. Nashiri had orchestrated attacks on military targets in a foreign port and so would be charged with violations of the law of armed conflict. Regardless of what happened to KSM, Nashiri would stand trial before a military commission.

As chief prosecutor of the Nashiri and KSM military commissions, Brigadier General Mark Martins follows in the line of the great Nuremberg jurists, Robert Jackson and Telford Taylor, but also in a far less auspicious one: he is the sixth chief prosecutor in the commission’s ten-year existence. On a cloudless day in mid-June of this year, in an old hangar that houses the Media Operations Center at Gitmo, Martins begins his press conference with a reminder and an expression of thanks. The reminder is to drink plenty of water; the summer sun is powerful in Cuba, brutal by midday. This gesture — the seasoned soldier acting as guardian of his less experienced charges — is protective but not condescending. The thanks are directed to the small group of journalists who have traveled down for this week’s pretrial hearings. Here again the tone is understated and sincere. Martins is well aware of the crucial role that reportage will play in shaping the public’s understanding of the commission. Legitimacy, a court’s most precious endowment, is, as the Supreme Court once observed, a “product of substance and perception.”

Before becoming chief prosecutor, in 2011, Martins worked closely with legislators and Obama Administration lawyers to redesign the commissions, which now, he emphasizes, look a great deal more like Article III courts than they once did. Statements acquired through torture or inhumane interrogation are barred. Guilt is determined by a military jury, called a panel, and the government must prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt. In certain respects the commissions represent an improvement over the court-martial system, as defendants facing capital charges, such as Nashiri, must be provided “learned counsel” (lawyers with extensive experience in such cases, like Rick Kammen), a right not granted ordinary soldiers facing a death-qualified court-martial. Differences remain between the military commissions and civilian courts — why else create a separate system? For example, the commissions permit hearsay that would likely be barred in an Article III court. But as Martins notes, so, too, do the international tribunals in The Hague — the Yugoslavia and Rwanda war-crimes tribunals, as well as the International Criminal Court. I recall a conversation I had some years ago with Geoffrey Nice, the British barrister and human rights activist who prosecuted Slobodan Miloševic. “It is well nigh impossible,” he remarked, “to conduct complex war-crimes prosecutions, where evidence often comes from sensitive sources, using standard common-law rules of evidence.”

More than just its chief prosecutor, Martins has become, by virtue of his impeccable credentials and reputation for integrity, the public face of the commissions, their last, best chance of demonstrating adherence to the rule of law. First in his class at West Point, Rhodes scholar, Army Ranger, and Harvard J.D., he is also faultlessly courteous, with a scholarly manner and a seriousness of purpose that immediately command respect. To get the word out about the revamped commissions, he has lectured widely and arranged for public viewing by CCTV of the proceedings at locations back in the States. Whether these efforts can alter the perception of illegitimacy — the principal legacy of the commissions’ disastrous first decade of existence — remains to be seen. “If . . . observers withhold their judgment of the reformed military commissions until they observe a trial firsthand,” Martins says, “I believe that they will see a system that is fair and legitimate and deserving of their confidence.” It is, as he is well aware, a big if.

After the ELC’s warehouse exterior, the high-tech courtroom — with its dark wood desks, built-in computer monitors, and sleek black ergonomic office chairs — offers something of a surprise. It looks a great deal like the equivalent facilities in The Hague. The viewing gallery can accommodate just under fifty spectators; today about two thirds of the seats are taken. Those on the right are reserved for survivors and members of victims’ families, who, should they desire privacy, can draw a heavy purple curtain to separate their seats from those of the journalists, NGO workers, and other observers seated on the left. During my previous visit, I had the chance to talk to some survivors and family members of victims, all of whom strongly supported the Nashiri commission. When asked what penalty they would like to see the defendant receive, to a person they said death. Joe Pelly’s wife, Sharon, volunteered, “If you need someone to execute him, I’ll do it myself.”

The journalists and NGO workers tend to be far less convinced by the happenings in the courtroom. Typically, the ACLU, Human Rights Watch, and several other NGOs will send down representatives to observe the week’s proceedings and report back; the ACLU’s periodic updates often end with the same coda:

Since they began, the ACLU has been visiting Guantánamo Bay to report on the systemic flaws in the Military Commissions and call for its closure. As the trials proceed, the cracks in the facade just keep growing.

The journalists on the whole do not disagree. This week’s group is modest; just seven of us are on hand to report on the Nashiri motions. Next week, when attention shifts to the 9/11 case, that number will triple as journalists from Der Spiegel and the Irish Times and Le Temps flock to Gitmo to moralize on American incompetence and malfeasance. Besides me, this week’s group is split between three extremely experienced journalists, who know the material intimately, and three younger bloggers, one of whom spends the week arguing that the true war criminals are George W. Bush and Dick Cheney and writes a post entitled “The Imperialist and Racist Origins of the Guantánamo Penal Colony.”

The day’s first order of business is a mere formality. At issue is the withdrawal from Nashiri’s defense of a lawyer who wishes to pursue a fellowship for postgraduate work at Harvard. Permission to do so can be granted only by the presiding judge, an Army colonel named James Pohl, who presides over the 9/11 case as well. Pohl will agree only once he establishes that the change is acceptable to the defendant. Nashiri sits at the far end of the defense table in short-sleeve white prison garb. He looks fit — Kammen confirms that his client is not participating in the hunger strike that includes more than a hundred detainees — and younger than his stated age of forty-eight. Beardless, but sporting perhaps a day or two of stubble, Nashiri is not particularly devout, rarely if ever making use of the prayer breaks scheduled throughout the day. He told American investigators that he was a millionaire by age nineteen, but Kammen dismisses this claim as “absolute bullshit.” An FBI source once described Nashiri as “someone who would commit a terrorist act ‘in Mecca, inside the Kaaba itself’ if he believed the cause demanded it,” yet his demeanor in court is polite and attentive. He has not yet entered a plea, but he is participating in the proceedings. He stands when Pohl enters — a small gesture, but one that Slobodan Miloševic notably withheld at his trial in The Hague. During the proceeding, Nashiri swivels slowly in his chair, following the simultaneous interpretation on headphones.

The exchange lasts only a couple of minutes. Pohl asks Nashiri whether it is his “free and voluntary choice” to let the lawyer leave the team, and whether he likewise accepts Captain Daphne Jackson, an Air Force JAG now seated at the defense table and visibly pregnant, as a replacement. Nashiri answers, “Yes, I agree to that,” first in Arabic and then in English. The brief, respectful back-and-forth exemplifies the detailed procedures that govern the revamped commissions; anyone who denies the reality of these procedures, or dismisses them as mere persiflage, either does not understand how a legal system works or does not want to see how the court actually acts.

All the same, the commissions’ attention to the autonomy and dignity of the accused doesn’t entirely square with the backstory of the government’s treatment of Nashiri. For all the attention given to the commissions’ flaws — that they allow hearsay, violate rights of confrontation, theoretically permit certain coerced statements to be used as evidence — the most troublesome aspect of the government’s case against Nashiri oddly tends to get overlooked. Like many other detainees, Nashiri was subjected to “enhanced interrogation” — stress positions, sleep deprivation, forced nudity, and other forms of degradation. But as one of the highest-ranking Al Qaeda figures in custody, Nashiri also came in for special treatment. Between being shuttled from one CIA black site to another, Nashiri was twice waterboarded. The CIA also performed mock executions in which Nashiri was bound, stripped, and hooded before a power drill was placed near his head — torture, plain and simple. The CIA actually maintained videotapes of his waterboarding, but later destroyed them amid concerns about the legal exposure of the interrogators.

The government acknowledges that this torture has left Nashiri with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Indeed, the prosecution petitioned the court to have Nashiri undergo a psychiatric exam, which the defense agrees was conducted with sensitivity, competence, and thoroughness. This exam determined that in addition to PTSD, Nashiri suffers from “Major Depressive Disorder” and “Problems related to interaction with the legal system” (we can only look forward to the day when the latter is recognized in the pages of the DSM). Nevertheless, the exam found Nashiri fit for trial — able to understand the charges against him and to participate in his own defense — a conclusion his lawyers largely accept. For its part, the prosecution concedes that evidence acquired through Nashiri’s torture cannot and will not be used at trial. The prosecution also successfully petitioned Nashiri’s guards to transport him to court without belly chains, as this security precaution apparently strongly reminded the defendant of his years of mistreatment.

As welcome as these developments are, they miss the deeper point. The government’s position is that strict adherence to the new procedures is enough to rectify the history of substantive abuse. The Constitution’s due-process clause bars the government from denying a person “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law” — the implication being that the government can deny all these things if due process is provided. But as the Supreme Court has noted, the due-process clause has “been understood to contain a substantive component as well, one ‘barring certain government actions regardless of the fairness of the procedures used to implement them.’ ” In constitutional law, the doctrine of “substantive due process” bars the executive from actions that “shock the conscience” — even if those actions follow all the proper procedures. The standard is admittedly subjective, but its application to the case against Nashiri is irresistible: the government is seeking to execute a man it systematically tortured. Consider my conscience shocked. Maybe any punishment should be considered unfair given the facts of Nashiri’s treatment, but at the very least we should recall the Supreme Court’s necessary insight: Death is different.

The problem, of course, is not unique to the military commissions, which perhaps explains why it is not high on the NGOs’ list of complaints: Justice Department prosecutors almost certainly would have sought the death penalty had Nashiri been charged in federal court. The irony is that the military commission must now do better. A federal court need not labor to persuade a domestic and international audience of its basic fairness. One can readily imagine the political pressures that led the government to forward capital charges against Nashiri. Joe Pelly notes that he takes medication for his own PTSD and mentions the case of Johann Gokool, a petty officer who lost a foot in the Cole blast and later committed suicide. “We were tortured, too,” Pelly says. “Every night I have visions of what I had to deal with that day.” Yet however much these expressions of anguish may move us, we court moral danger when we use the same word to describe the suffering of Pelly and the treatment of Nashiri.

Along with many of the soldiers who guard and maintain the military commissions, the journalists and NGO workers are quartered in Camp Justice, a gridlike collection of tents that dot the former landing strip of McCalla Field. The tents, which look like Quonset huts and sleep six, call forth thoughts of Scott and Shackleton thanks to overly aggressive air-conditioning, while the military showers spray nothing but scalding water. It’s hardly the most agreeable arrangement, but thoughts of my own personal comfort seem inappropriate. Shaving one morning, I hear a soldier next to me mutter, “I’m so sick of this fucking place” — not, I learn, an uncommon sentiment. Another soldier tells me, “It’s not just the detainees who are tired of Gitmo. People don’t often think about the stress on the guards.”

Gitmo’s detention camps occupy a small part of the naval base, but they have proved toxic to the reputation of the commissions, the base, and the nation. If the commissions are to succeed in legitimizing themselves, they will have to sever their connection to the camps. This could happen in one of two ways. A commissions official who gives me a guided tour of the Expeditionary Legal Complex places emphasis on the word “expeditionary.” The court building, he notes, was designed to be moved; it could be placed on a barge and relocated to, say, a military base in the continental United States. That would further delay the already sluggish progress of the Nashiri and 9/11 cases, and other legal and political complications stand in the way, but when asked whether he would move the commissions stateside if he could, General Martins looks cautiously tantalized. His only comment is to note that the 2009 law reforming the commissions is silent as to venue.

Or the commissions could stay and the camps themselves could finally go. They have been in the news again recently, both because Obama has renewed his pledge, made the first week of his first term, to close them down, and because of the detainee hunger strike that prompted his announcement. I was able to visit the detention camps during an earlier trip to Gitmo in February, around the time the current hunger strike began. If the strike was already under way, it certainly wasn’t mentioned during my tour; the officer in charge of Camp 6, where most of Gitmo’s remaining 166 detainees are interned, mentioned obesity as one of the biggest problems facing his inmate population.

Our first stop was Camp X-Ray, a twenty-minute drive up Sherman Avenue, Gitmo’s main thoroughfare, past the McDonald’s and the Subway, past the “high-rises” where the lawyers stay and the high school for the dependents of those stationed at the base. Eventually we reached a remote spot close to the northeast border with Cuba proper. Closed down eleven years ago, the abandoned camp is small and now heavily grown over with dry grass, its wooden guard towers warped and sagging. Plans to raze X-Ray were put on hold by a court order preserving it as a putative crime scene. As the first of Gitmo’s numerous camps, it was in use for only a hundred days but produced the images that remain indelible in the public consciousness: detainees, clad in orange jumpsuits and blackened goggles, on their knees in open-air cages. Just outside the tangle of razor wire are dilapidated wooden huts where, a decade ago, men in polo shirts and chinos would stroll over to conduct “interviews.”

Later, we drove over to Radio Hill, where the present detention complex is located. Camp Delta, a sprawling facility surrounded by white bollards, is now all but empty; currently it houses a behavioral-health clinic. The road cut toward the coast and we passed Camp Iguana, home to the base’s last group of Uighurs, a Turkic ethnic minority some of whose members got caught up in America’s dragnet in Afghanistan and Pakistan. The camp is named after Guantánamo’s most famous and protected local fauna. Iguanas roam freely and abundantly — shortly after I arrived for the first time I was introduced to one named Holy Fuck, who is often seen resting by the entrance to the commissary. The speed limit on the base is strictly enforced at twenty-five miles per hour, and the fine for killing an iguana allegedly runs up to $10,000. Camp Iguana occupies a spectacular spot on a rocky bluff overlooking the Caribbean Sea. The Uighurs were slated to be discharged five years ago, and they are not alone in this regard: eighty-nine detainees recommended for release have been waiting more than three years for their freedom, their transfer delayed by congressional intransigence and presidential inaction.

Camps 5 and 6 house almost all the rest of the detainees; Camp 6, the equivalent of a medium-security prison, is reserved for compliant detainees, who, at least until the hunger strike this year, represented a majority of those remaining at Gitmo. Detainees here have the opportunity to take language and art courses. There is a library stocked with Harry Potter in Arabic and Pashto and other books whose titles resonate provocatively: Gabriel García Márquez’s News of a Kidnapping, H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds, and John Grisham’s The Innocent Man. There are TVs and video games. (According to a public-affairs officer, one detainee “only wanted a DVD of Brazilian Butts. He was very insistent, but that was a no.”) “It’s a whole lot nicer than where we keep our soldiers,” a military lawyer on the tour ruefully commented. “Have you ever seen Leavenworth? What a dump.” But Leavenworth is a prison, where persons convicted of criminal wrongdoing are incarcerated. After years of confinement, none of the detainees in Camp 6 have ever been charged. The only thing that has changed is that they are no longer designated “unlawful enemy combatants”: Congress improved that in 2009 to “unprivileged enemy belligerent.”

Now, during my June visit, the camps are in lockdown. More than forty of the hundred hunger-striking detainees are being force-fed. And yet there is a feeling — optimism would be too strong a word, more a sense that the sheer accumulation of frustration and despair has overcome the inertia, and that finally something will change. Those slated for release might actually be released; those who can be charged with crimes might actually be charged; and the administration might even figure out what to do with the forty-six detainees whom it deems too dangerous to release but is unable to try, presumably for lack of adequate or usable evidence. I ask a Marine lieutenant colonel what he would do with this last group, and his answer is unequivocal: “You can’t hold them forever, no matter how much they want to hurt us. You’re talking about forty-six guys against the United States military. C’mon.”

Can a spiral notebook be weaponized? The question consumes an afternoon session, and represents another challenge facing Martins: dealing with Kammen’s kangaroo strategy, which aims to show at every turn that the case remains trapped in “a truly bizarre world,” a grotesque simulacrum of law.

Well into his sixties, Rick Kammen still has something of the bad boy about him. He merrily recalls a trial from years back in which a judge invoked the Chicago Seven, addressing Kammen as “Mr. Kunstler” — to which he responded, “Good morning, Judge Hoffman.” A native of Indianapolis, he speaks with a soothing Midwestern twang and is gifted at making life miserable for the government, perhaps in part because the government is quite good at making life miserable for itself. There are numerous stakeholders in the case — the joint task force that oversees the camps, the intelligence communities, the secretary of defense — and Martins’s delicate task is complicated by all of them. Until recently, Kammen, who likes to use spiral notebooks, has been allowed to bring them to meetings with his client. A new rule changed that: forthwith spiral notebooks were to be considered contraband. The commander responsible for the change, an Army colonel named John Bogdan, soberly explains to the court that the wire from the notebook could be removed and fashioned into a garrote. Kammen is incredulous. “Have you run any experiments on how long it would take to remove the wire from a spiral notebook and turn it into a garrote?” Colonel Bogdan admits that he has not. Kammen hands Colonel Bogdan a spiral notebook. “We’d like to see how long it takes.” A prosecutor leaps to her feet. Objection! Sustained. “Would you allow a three-ring binder, or is that also too dangerous?” Kammen asks. The commander demurs. “I’d have to see it.”

At some point, Judge Pohl notes, “You don’t want to know what I think of [this] issue.” Laughter is heard throughout the courtroom, but not from the prosecution’s desk. The last thing the prosecution wants is to be dragged into an unseemly fight over notebooks, but it can’t afford to abandon the beleaguered commander, and so counters with an appeal to principle: Is the court really prepared to substitute its judgment of what constitutes a security risk for the expert’s? Despite his quip, Pohl, who describes himself as “a linear guy,” follows the dispute attentively, his only sign of impatience a habit of repeating, “I got it. Okay, got it.”

Then there is the matter of surveillance. As at its sister facilities in The Hague, the ELC’s spectator gallery is separated from the court proper by layers of bulletproof and soundproof glass; spectators actually follow the proceedings on TV monitors mounted at the front of the gallery. These provide both picture and sound — on a forty-second delay. This arrangement takes some getting used to — you watch, for example, Judge Pohl enter the courtroom, take his seat, and open his mouth; then, forty seconds later, the whole thing repeats on the monitors, now with sound.

This protocol, familiar to those who followed the trial of Saddam Hussein (an association the commissions do not necessarily want to invite), is meant to protect classified information. Should sensitive material come under discussion, Judge Pohl or the court security officer can push a button, muting the transmission and illuminating a light by the judge’s bench that flashes red, much as if a hockey goal had been scored. During a 9/11 hearing in late January, the hockey light flashed and white noise filled the speakers, all without Judge Pohl lifting a finger. Evidently the mute button had been activated by what the parties called the OCA — the “original classification authority,” apparently the CIA. Judge Pohl, either previously unaware of the CIA’s power or furious at its brazen use, threatened to have a “little meeting” with any “external body” trying to control his proceeding. The next morning, he summarized in open court what the public had missed during the three-minute gap, reminding anyone who was listening that “only the judge has authority to close the courtroom.”

The damage has been done. The Nashiri hearing, which followed directly on the heels of this episode, became bogged down in a lengthy debate as to whether the entire courtroom was nothing more than, as one defense lawyer put it, a “huge listening device.” Members of the defense moved to a far corner of the courtroom to confer in whispers, suspicious (or at least performing the suspicion) that microphones at their table might be wired to the OCA — now referred to as the “man behind the curtain.” The measure prompted a prosecutor to drily observe, “We have some theatrics going on.” Of course the defense was engaging in theatrics — why else put a stuffed kangaroo on your desk? — and effective theatrics at that. The suggestion that the very agency responsible for torturing Nashiri now controlled the courtroom and could bring down a curtain of white noise when discussion turned to the matter of Nashiri’s abuse struck at the core of the commission’s credibility.

Kammen, understandably, was not about to let the matter go away. At issue at the June hearings is a smoke detector. Nashiri, KSM, and the dozen other “high-value detainees” are housed in Camp 7, an ultrasecure facility the very location of which is a secret — except perhaps to anyone who cares to look at Google Maps, which shows it ostensibly occupying an isolated spot on Radio Hill. Because even Nashiri’s lawyers are not permitted into Camp 7, meetings take place at a separate facility called Echo II; smoke detectors in the meeting rooms were recently discovered to conceal audio monitoring devices. The commander of the camp, the same Colonel Bogdan known for his cautious approach to notebooks, acknowledges the audio capability but steadfastly insists that it has never been used to monitor attorney-client conversations. Kammen makes Colonel Bogdan’s time on the stand most uncomfortable, as an increasingly glum-looking Bogdan attempts to explain how he managed not to know or be apprised of the monitoring device until six months into his command. The prosecution points out that the defense has proffered no evidence that monitoring has occurred. It has simply moved from capability to actuality, and now is asking the government to prove, as one prosecutor puts it, “that dragons don’t exist.” Unfortunately for the prosecution, the day’s headlines trumpet the name Edward Snowden. If the NSA essentially eavesdrops on everything always, is it so preposterous to believe the government would eavesdrop on a conversation between a senior Al Qaeda lieutenant and his lawyers?

The last day of this round of proceedings also does little to advance Martins’s larger goal. The motion to be discussed deals with classified material; in fact, its very subject is classified and so is known among the press simply as the “unnamed motion.” Journalists are prohibited from the courtroom, as is the accused, an arrangement Kammen claims is unheard of in a capital case. The session does not last long, some seventy-nine minutes, and the following week, the military commissions website publishes a version of the transcript with whole pages blacked out. In the press conference that directly follows, Martins is at pains to emphasize that federal law allows such closed sessions in civilian court, too, and that the trial itself will be open and public, relying on evidence available for general scrutiny.

The defense treats that explanation with a degree of skepticism largely reflected in the reports of the media and NGOs. But here again, to conclude that the government is merely feigning an interest in transparency is fundamentally to misunderstand its position. More than anything, the prosecution needs to open the trial up, for every time it is forced into closed session, it revives the history of Nashiri’s secret torture.

If the week’s hearings make plain enough the exceptional problems the government faces as it seeks to promote its commissions, they also reveal something self-defeating about the arguments of the defense. No doubt Kammen is correct that a federal court, unhampered by the struggle over legitimacy that makes this proceeding at times absurd but more often fascinating, could try the case more smoothly and expeditiously. Yet the very ease of the process would simply hurry Nashiri toward a likely conviction. Speed was to have been a key virtue of Bush’s original commission; now the need to air questions that would already be settled in federal court arguably works to the defense’s favor. As for Kammen’s artful efforts to paint the prosecution and the commission as the unreconstructed toadies of the “other stakeholders,” the very openness of the debate, the vigor of the adversarial proceeding, the clarity and professionalism of the prosecution’s rebuttals, and the steady, patient, practical stewardship of Judge Pohl powerfully suggest that something more complex is happening in the courtroom.

But if the government is to be successful in justifying its processes, it will have to come to terms with the substance of what it is trying to do. Unlike General Martins, Kammen is not a student of Nuremberg. But when we share a meal at Washington’s Ronald Reagan National Airport during our return home from Gitmo, he removes a Kindle from the backpack in which he also keeps his stuffed kangaroo and shows me a book he has read closely. Its subject is the controversial Malmedy trial of 1946, in which the American military prosecuted seventy-three members of the SS accused of massacring scores of American airmen during the Battle of the Bulge. The trial, which was held at Dachau, resulted in dozens of convictions, including numerous death sentences. Later, allegations emerged that American interrogators had beaten and abused their SS captives. Though never fully proved, these charges made front-page news in the New York Times and led, amid escalating Cold War tensions and a strengthened commitment to secure Germany as an ally, to the decision to commute all the death sentences. In 1956, the last of those convicted of massacring American soldiers walked out of Landsberg Prison a free man. The case and the commutation remain controversial among historians, and the meaning of the incident is far from simple or clear. But it is fair to see it as standing for a principle fundamental to our system of law and justice: that America does not execute men whom it has tortured.