Discussed in this essay:

The Rule of Barbarism, by Abdellatif Laâbi, translated from the French by André Naffis-Sahely. Archipelago Books. 146 pages. $12 (paper).

The Bottom of the Jar, by Abdellatif Laâbi, translated from the French by André Naffis-Sahely. Archipelago Books. 232 pages. $17 (paper).

Toward the end of The Bottom of the Jar, a memoir of growing up in the city of Fez, the poet Abdellatif Laâbi recalls the moment of his political awakening. It is 1955 and the Moroccan independence movement has caught fire, spreading across the country and hastening the end of the French protectorate established in 1912. The official press blames the disturbances on outsiders and terrorists, but no one is fooled. Piecing together news reports with what they see and hear in the streets, Laâbi’s family find they are living through one of history’s turning points:

We discovered a country, with cities and diverse populations, a north and a south, an east and a west, and that the whole of it was bent back like a bow, overcome by the same worries, knocking on the same door, hoping for salvation, bleeding for the same cause, committed to making the same sacrifices. One magic word summed up all the expectations and the refusal to wait any longer for their realization: istiqlal! The walls of our Medina were festooned with slogans scrawled with charcoal, where the word “independence” was prominently featured . . . Demonstrations took place every day and were quickly repressed by the security apparatus. The police stations in Nejjarine and Boujeloud were filled to capacity.

The slogans have changed, but the drama is familiar: a popular uprising, a cycle of protests and repression, jails filled to capacity. The current season of revolt in the Middle East, now almost three years old, has many precursors. The modern history of the region can be told as a series of revolutions and counterrevolutions, first against the colonial regimes, then against their successors. Each of these revolts has found poets to celebrate and memorialize it. When young Moroccans took to the streets on February 20, 2011 — nine days after Hosni Mubarak resigned the presidency of Egypt and about a month after the Tunisian military deposed Zine El Abidine Ben Ali — Laâbi, writing from Paris, called it “the hour of truth.” He dismissed the idea of a “Moroccan exception” — the thesis, especially popular with the Moroccan elite, that the country stands apart from regional trends — and warned the government that the “shock wave radiating out from Tunis will spare no Arab regime.”

Unlike their American peers, Arab poets are public intellectuals. At moments of crisis, readers expect them to take sides. In Memory for Forgetfulness, his recollection of the 1982 Israeli siege of Beirut, the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish complained that such expectations were unrealistic:

In response to cultural residues within us that link the war cry to stirring verse — survivals that assume the poet’s role is that of a commentator on events, an inciter to jihad, or a war correspondent — the Arabic literary milieu has become used to posing the question of poetry in the middle of raging war. In every battle they raise the question, “Where’s the poem?”

Yet Darwish wrote many poems, including some of his best, in the middle of wars, revolts, intifadas. The same is true of Laâbi, one of Darwish’s most able translators. His finest poems are virtuosic performances, turning political crises into poetic occasions and combining a flair for self-dramatization with stunning verbal inventiveness.

The recent series of uprisings has not lacked for poetry. The region’s most widespread slogan, “The people want the fall of the regime,” is borrowed from a line by the Tunisian poet Abu al-Qasim al-Shabi. Egyptian poets often held the stage in Cairo’s Tahrir Square, with the demonstrators sometimes incorporating their verses into chants. And rappers have given the so-called Arab Spring its sound track. “Rais Lebled” (“President of the Country”), a song by the rapper El Général, is frequently called the anthem of the Tunisian revolution.

Look at the policeman with his stick,

Tak-a-tak, what does he care?

There’s no one to tell him to stop,

Even the constitution is written in water.

In Morocco, the rapper El Haqed has become a hero for the protest movement. His song “Kilaab Addawla” (“Dogs of the State”) was released on YouTube with a video showing a policeman whose head had been digitally replaced by a donkey’s. Both El Haqed and El Général were jailed for their work. Their experiences remind us of those of Laâbi and many other Arab poets, for whom outspokenness and imprisonment have often gone hand in hand.

Morocco won its independence from France in 1956, in a struggle commonly known as the Revolution of the King and the People. The name suggests some of the claustrophobic intimacy of Moroccan political life, in which the palace sucks up most of the available air. The newly sovereign king, Mohammed V, was a popular ruler, but no Moroccan monarch has governed without serious and sometimes violent opposition.

Two years after independence a rebellion broke out among the Berbers of the northern Rif Mountains. Mohammed sent in the Royal Army under the command of his son, Crown Prince Hassan, and troops killed thousands of Riffians, poisoning relations between the new government and its rural subjects for decades. When Hassan became king, in 1961, he confronted a growing leftist movement of students and labor unions. His regime responded with a campaign of detentions, torture, and disappearances, the beginnings of a dirty war that Moroccans call zaman al-rasas, “the years of lead.” In 1965, police killed dozens of student protesters in Casablanca; later that year, Mehdi Ben Barka, leader of the left’s largest political party, was arrested by French security officials in Paris and never seen again. Royal involvement has not been proved, though it is widely suspected.

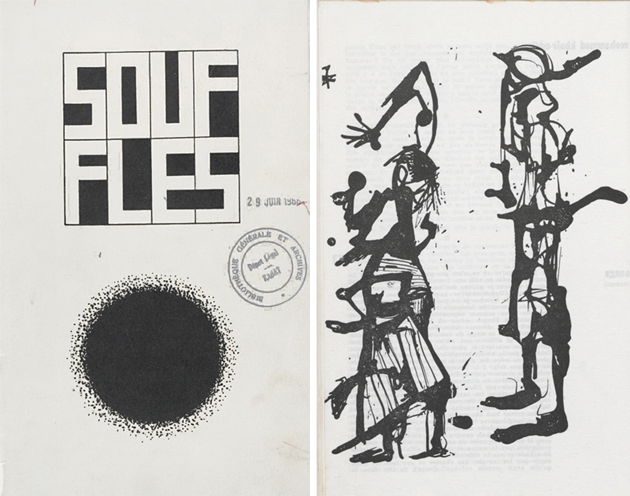

Cover and interior page, with illustrations by Mohammed Bennani, of the second issue of Souffles. From the Bibliothèque Nationale Royaume du Maroc

Rural uprisings, student protests, political assassinations — such were the provocations behind Laâbi’s decision in 1966 to launch Souffles (French for “breaths”), a magazine that in its six-year existence became legendary throughout the Middle East. Several of Morocco’s best-known modern writers, such as the novelists Tahar Ben Jelloun and Abdelkébir Khatibi, were early contributors to the magazine, which ran mostly poetry and cultural criticism. The poems Laâbi wrote during this period were later collected in Le règne de barbarie, now translated by André Naffis-Sahely as The Rule of Barbarism. Laâbi was twenty-four years old when he founded Souffles; these poems are his earliest published works.

Laâbi did not grow up around books. His father was a basket weaver in Fez’s old souk, and his mother never went to school. After primary education in local French schools, Laâbi went to university in Rabat, where he read Brecht and Arrabal and attended a lecture by the French poet Pierre Emmanuel, “Le souffle et la parole” (“The Breath and the Word”), about torture in Algeria. “One of the reasons I started to write was for the men and women who are not able to express themselves,” Laâbi told the Parisian literary journal Double Change in 2001, “to allow them to speak, to have something to say.” His first works crackle with the excitement of a voice breaking into speech for the first time. The poems are for the most part long, ranging from five to twenty-three pages, and written in a mood of feverish lyricism. Posturing (“Here I am / right here / held in velvet night / bristling with wasps”) and menacing addresses to the reader (“Who told you I wasn’t a cannibal?”) alternate with obscure and violent imagery (“Flocks of nocturnal suns / distress like a nosediving plane / the fire advances / on the dykes”).

Laâbi’s poems are inseparable from the magazine in which he published them. The mission of Souffles was what Frantz Fanon, the Martinican-born spokesman for the Algerian revolution, called “cultural decolonization.” For Laâbi and his collaborators, Morocco had won political independence from France without also winning its cultural independence. Colonial ways of thinking, with their racial categories, historical schemas, and hierarchy of literary forms, still held sway in the Morocco of the 1960s, as they did elsewhere in North Africa. What Souffles aimed at was the creation of a new culture, one that would tear itself free of the recent colonial past and plant itself in the deeper soil of Morocco’s Arab and Berber history.

There was an obvious irony to this ambition: the effort to rid Moroccan culture of colonial residues was carried out in the colonizer’s tongue. All twenty-two issues of Souffles were published in French. One result of this conflict is that the poetry of Souffles bears a tortured relation to its language. The magazine’s editors and contributors applied Fanon’s dictum from The Wretched of the Earth — “The colonized man finds his freedom in and through violence” — to literature. They wanted to rough up their French, to shrug off its classical conventions and replace them with what Laâbi called “electrified idioms.” In one of his first editorials, Laâbi wrote, “The task of this country’s writers is to take apart their own language, to do violence to it so that they can root up all its possibilities.” This is a demand for literature at war with its own means of expression, and Laâbi’s poems — fractured, hermetic, convulsive — bear witness to the struggle.

“Stagnations,” one of the earliest poems in The Rule of Barbarism, rages against a culture of quietism. The poet accuses his countrymen of speaking in dead platitudes, “how-are-you-and-health-that’s-what-matters,” and harmless pleasantries, “your cigarette butts of hope / your day-to-day mockery,” while their country is brutalized. The poet offers his own speech as a counterexample. Laâbi’s stanza, in these poems, looks like a broken staircase, with multiple indents and irregular line lengths. There is no obvious place to catch a breath. So the reader shares some of the poet’s physical discomfort in the utterance of his words: “my body heaves / a poem contorts me / I ejaculate it / place it under your microscope slides / it’s only a vaccine I offer you.” His writing wants to purge itself — by vomiting, or ejaculation — of its own language. Offering the poem as a vaccine, in which infection and cure are one, is thus grimly appropriate.

The Souffles poets also wanted to reclaim their country from the clichés of travel agencies and anthropology textbooks (“Let’s say we are instinctively allergic to textbooks,” Laâbi writes in one poem). The guidebook version of Morocco is a land of enticing oppositions: the modern and the medieval, the busy souk and the open desert, high-rises in Casablanca and riads in the mountains. Here is Laâbi’s dissection of this Disneyland:

be good now

my dear land of contrasts

the ethnologist and the scholar are coming

the gifts of flour and medicine are coming

do a cartwheel my dear country of catos and brutuses

we’re going to shoot some artsy photographs

you’ll have your portrait in a living museum

well-framed

with precise captions . . .

the well-mannered tourists are coming

you’ll get small change in weighty currencies.

Souffles published many articles probing the layers of Moroccan history, and Laâbi’s poetry often casts itself as an archaeological enterprise. In “Eye of the Amulet,” the poet calls himself an “unearther of ruins” and asks the reader to “hear idioms collide / in my mouth.” This evocation of Morocco’s pluralism is not only a rebuke to brochure writers; the same pluralism has been largely ignored by the post-independence regime, which has emphasized Morocco’s Arab identity while neglecting the half of the population that is estimated to be Berber (censuses do not distinguish between the two). Laâbi’s solidarity with marginalized groups — “the aphasic tribes,” as he calls them — is important for his poetics. His works often declare themselves as oral performances rather than written texts, another symptom of his allergy to classicism. “Don’t read / listen,” is one of the ruling imperatives of his verse. “Don’t look for me in your archives,” he writes in “Eye of the Amulet,” “I am by nature not of the written / rather search for me in your entrails / when fugitive verses / twist your guts.” Seen from the perspective of this history, the French occupation becomes merely a moment of sound and fury, and a relatively short one at that.

“Race” is Laâbi’s best poem of unearthing, and it is also the longest poem in the collection. It is in part a rewriting of “Mauvais Sang,” the opening section of Rimbaud’s Une saison en enfer, a text that lies behind many poems of decolonization written in French. “It’s clear to me that I belong to a lesser race,” Rimbaud’s wild-eyed poet boasts. “My race sang upon the rack; I don’t understand your laws; I have no moral compass, I’m a beast.” “Race” evokes an indigenous Moroccan people, “the race of Atlases” — the name of Morocco’s northern mountain range, inhabited mostly by Berbers — whose history has been subject to an “anonymous burial.” The Atlases are not a specific people so much as a group name for all of Morocco’s heterodox communities: wandering dervishes, Sufi brotherhoods, Berber tribes, “the scarred and the stateless,” as Laâbi calls them. The poem looks forward to when the repressed history of the Atlases will erupt out of “the volcano’s heart.” It features some of Laâbi’s strangest and most rapturous language, chanted by a poet as old as the elements:

there was no water at the beginning

but a vast sweep of dunes like a floating caravan of

continents

a rolling of dunes

there is only the steady beat of mutations

a rising of carnivores

and me crocodile-bard

revelling in lava.

The Six-Day War signaled a sea change in the editorial policy of Souffles. Along with many other intellectuals, Laâbi was radicalized by what Arabs call the Naksa, or “setback.” The comprehensiveness of the Egyptian, Jordanian, and Syrian regimes’ defeat revealed the bankruptcy of their ideologies as much as the feebleness of their armies. Laâbi’s magazine became increasingly international and aggressively left-wing. The range of articles published in Souffles during this time is impressive. One issue in 1969 featured an essay by the Havana-based Haitian poet René Depestre, an interview with the Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembène, and the Ten Point Program of the Black Panthers. At the same time, the magazine’s commentaries on the politics of the Arab world became more pointed. It denounced a trend toward Western-friendly authoritarianism as well as the abandonment of Palestinians. And in a move that signaled doubts about their strategy of cultural decolonization, the editors created a sister publication in Arabic, Anfas (Arabic for “souffles”). By 1972, the two publications had been banned, and Laâbi had been arrested. He spent the next eight and a half years in Kénitra prison, just north of the capital, where he was frequently tortured.

Incarceration has been a rite of passage for generations of Arab intellectuals. Laâbi later wrote that prison was his “school for liberty,” and perhaps the most consequential reading he did in Kénitra was of Palestinian poets such as Mahmoud Darwish and Samih al-Qasim. Laâbi’s interest in what was then called resistance poetry had to do with technique as much as with solidarity. He was especially drawn to Darwish’s style of radical balladeering, which combined eroticism, homesickness, and combativeness. Once released from prison, Laâbi published several translations of Darwish, an activity that seems to have reconciled, at least in part, Laâbi’s political and literary commitments, his Arabism with his francophony.

“No Walls to the Cell” is the title of a famous Darwish poem translated by Laâbi. The title is ambiguous; it announces the poet’s intrinsic liberty while also acknowledging that Palestinian life outside prison is only another form of internment. Following his release, in 1980, Laâbi made a similar discovery. He was deprived of his passport, banned from publishing, and continually harassed by the authorities. In 1985, he went into what he has called “voluntary exile” in Paris. The move had a marked effect on his poetry. In place of the defiant postures of his early verse, Laâbi’s more recent poems are subdued. The reader is often reminded of those classical Chinese poems written by scholars in forced retirement. They are full of questions rather than exclamations or ejaculations, and the lines tend to be epigrammatic rather than broken into pieces. They are also poems of retrospection. In “The Spleen of Casablanca,” a long poem written in 1995 after a trip home, Laâbi struggles to recognize in the shattered sidewalks, untended trees, and endless traffic the city he once knew. “No human heart / changes half so fast as a city’s face,” wrote Baudelaire, the original splenetic. But Laâbi’s nostalgia is not merely for a lost country or city. He also mourns an earlier, more active version of himself: “After vain deeds / vain words / leaving a yearning / for deeds.”

Laâbi’s memoir, The Bottom of the Jar, also translated by Naffis-Sahely, exhibits a similar strain of nostalgia. The book is a fond re-creation of Fez in the early 1950s, when Laâbi lived there as a schoolboy. It is a charming book, written by a poet very different from the one who wanted readers to wonder whether he might be a cannibal. The childhood memoir, or portrait of the artist as a very young man, is an established genre of Maghrebi literature, with its own repertoire of characters and scenes. Early on in his story, Laâbi acknowledges this tradition but promises to skip past the usual episodes — Koranic school (“which I didn’t frequent for very long”), circumcision (“which didn’t unduly traumatize me”), and the hammam (“where little boys are initiated into the great mysteries of women”). But many of his chapters revisit the genre’s conventions. Most pleasantly, there is an evocation of the old neighborhood — in this case, the labyrinthine medina of Fez — with its street games, itinerant vendors, storytellers, and Ramadan festivities. The memoir feels less like a narrative than a leisurely stroll, with time to spare for digressions and misadventures.

One reason for the popularity of childhood memoirs among writers of Laâbi’s generation is that it lets them tell two coming-of-age stories in one: their own and their country’s. These recollections are also tales of the transition between tradition and modernity, between the cozy world of family holidays and picnics and the new world of radio reports, mass politics, and young women with bobbed hair. In many of these memoirs, the hinge between old world and new is the French école. Going to school is often a moment of trauma, especially in earlier versions of the story, where the hero loses both his family and his language. It is a “second rupture of the umbilical cord,” as the Algerian novelist Kateb Yacine once wrote. (One also thinks of Stephen Dedalus’s anxious discovery, while debating an English dean, that “the language in which we are speaking is his before it is mine. How different are the words home, Christ, ale, master, on his lips, and on mine! . . . His language, so familiar and so foreign, will always be for me an acquired speech.”)

Somewhat surprisingly, Laâbi’s prose version of this episode is sweet and comical. Never having heard a foreign language before, the boy — whom Laâbi calls Namouss, a childhood nickname meaning “mosquito” — thinks the whole thing is a joke:

The first words [the teacher] uttered plunged Namouss into bewilderment. Not only did they sound strange but even the way he moved his lips, hissed between his teeth — and the loud scraping noises that rose out of his throat — were gestures and gutturals that Namouss didn’t know how to interpret. For a long time, he wished that this nonsensical flood would recede and that, adopting a more reasonable disposition, the teacher would start making some sense. All in vain.

Eventually he does learn to interpret the teachers’ words; he even becomes a model student. Earning a gold star for his pronunciation of bonjour, “He teetered between an immense sense of pride and the feeling that he’d betrayed his classmates.”

Such scenes hint at some of Laâbi’s old ambivalence toward French, a language he once wanted to violate, or vomit up. But the memoir is not overtly political. It is more like a family idyll in which the mother — Ghita, a profane, practical-minded woman who is also a repository of wisdom — has the starring role. The childhood portion of the memoir ends in 1955, with Moroccan independence still hovering on the horizon. But that story is framed by Laâbi’s account of a family gathering around his father’s deathbed in 1989. The television shows images of the fall of the Berlin Wall. This scene, too, is played for light comedy, and Ghita’s voice gets the last word: “ ‘Pahh, is that the only news they could find to tell us! A falling wall . . . it can’t have been built very solidly. The walls of Fez are still standing after all.’ ” Yet one cannot help feeling the scene has a symbolic seriousness, pointing toward the end of an era of leftist life in Morocco (and elsewhere), an era of revolutionary hopes followed by bitter defeats.

Those hopes were momentarily rekindled in February 2011, when Moroccan students and activists launched their own version of the Arab Spring, with large demonstrations in the major cities and a sophisticated social-media campaign. Laâbi immediately backed the protesters, whose politics were very close to his own. Since his relocation to Paris, Laâbi has written many articles in support of Morocco’s opposition, a fractured movement that has never quite recovered from the dirty war of the Sixties and Seventies. He has also been outspoken in his criticisms of local Islamist groups, who have been known to cooperate with the throne — now held by Hassan’s son Mohammed VI — against the secular left. The demands of Laâbi and the February 20 movement were mild by regional standards. They sought not the fall of the regime but the peaceful transition to a constitutional monarchy — a “modern monarchy,” in Laâbi’s slightly cockeyed phrase — committed to the separation of powers, the rule of law, and an end to the politics of the Makhzen, a closed elite of military officers, bureaucrats, and businessmen with strong ties to the palace.

The monarchy handled the protests with dismaying skill. Fewer than three weeks after the demonstrations began, Mohammed gave a televised address promising “comprehensive constitutional change” and an “elected government that reflects the will of the people, through the ballot box.” The proposed constitution, drafted by a committee selected by the king, was voted on in a referendum on July 1 of that year. It passed, according to official reports, almost unanimously. The new constitution seems to fulfill several of the protesters’ demands, promising a “constitutional monarchy” and the separation of powers in its first article. It also grants the judiciary greater independence and makes Amazigh, the tongue of Morocco’s Berber population, an official language. In practice, however, the palace maintains near absolute control over all important political decisions. By acting swiftly, and by putting constitutional reforms on the table right away, the king succeeded in sapping the opposition’s momentum. In the first parliamentary elections under the new constitution, held in November 2011, it was the Justice and Development Party, a hard-line Islamist organization, that won the most votes and from whose ranks the king chose a new prime minister.

From Laâbi’s perspective, it is hard to imagine a worse outcome for the Moroccan version of the Arab Spring. The king maintains his control while the Islamists have been strengthened. So too in countries across the region religious parties have achieved new legitimacy and in some cases outright control while “modern monarchs” remain on the throne. One wonders, given this result, whether the revolts will mark the reawakening of Laâbi’s brand of secular politics or its death rattle. Laâbi’s latest collection, A Zone of Turbulence, published in 2012, has little to say about the previous year’s events. It is a work that extends the rather metaphysical concerns of Laâbi’s recent poetry, and it is difficult to assign the speaker of these poems any particular history. Still, certain passages suggest how hard it has been for the young poet “bristling with wasps” to keep fighting: “in his lungs / the air gets thinner / as it does elsewhere / and his breath / once deep and hot / runs out in the middle of the climb.”