The protagonist and narrator of E. L. Doctorow’s twelfth novel, Andrew’s Brain (Random House, $26), is a clumsy cognitive scientist who relates the story of his life from an undisclosed location to an unnamed psychiatrist. His anxious monologue — interrupted occasionally by the analyst’s dopey questions — is at once marriage plot, 9/11 novel, and neuroscience brief. Andrew isn’t a very convincing proponent of his subject. His despair over the (misleading) finding that brains “make our decisions before we make them,” for example, tells us a good deal about his own fears and almost nothing about the problem of free will. Speaking of will: Andrew’s being held against his, and though he professes to be suspicious of the talking cure, he can’t shut up.

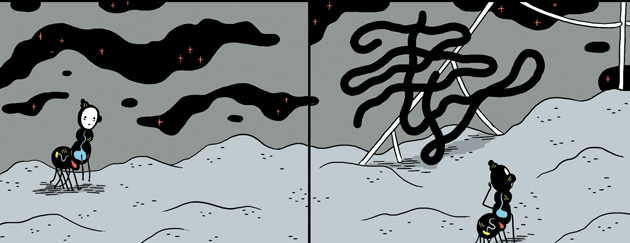

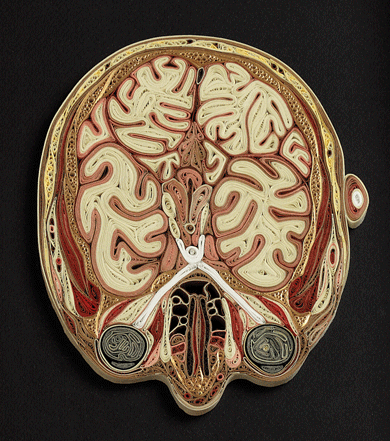

Head II, cross section in rolled paper, by Lisa Nilsson.

Courtesy the artist and Pavel Zoubok Gallery, New York City

The critic John Leonard once described Doctorow as two men, one liberal intellectual citizen and one visionary prophet, and Andrew is the hallucinating technician who results from combining both styles of thought in one character. He’s by turns antic and mournful, somber and joyfully in love, clinical and desperate, and he finds himself in situations tragic and pointlessly silly. (I refer you to the performing midgets.) He’s neglectful, or at least neglect has a way of finding him, as when the pharmacist sends the wrong medicine, and he feeds it to the baby, and the baby dies. His ex-wife’s new husband dubs him Sir Andrew the Pretender, “whose well-meaning, gentle, kindly disposed, charming ineptitude is the modus operandi of the deadliest of killers.”

The description sounds a bit like a certain leader of the free world, circa 2001 — and it turns out that Andrew is the old college roommate of that forty-third president of the United States. The two cross paths at a decrepit D.C. high school where Andrew has sunk to teaching teens science; POTUS just happens to swing by on a quick P.R. stunt. Fearful that Andrew will reveal to the press his collegiate habit of cheating on exams, the president appoints him to a special, short-lived government post. Andrew thinks about as much of old Chaingang and Rumbum as Doctorow himself does — “self-appointed world strategists” with “ranks of ideologues and think-tank warriors behind them” — and it’s not long after that he tells them off with an act of absurdity: a handstand in the Oval Office. That’s how he wound up wherever it is he’s wound up, remembering, or trying not to, how it is that he got there.

“Presidency VI,” a photograph of a life-size model fabricated from paper, cardboard, and confetti, by Thomas Demand © The artist/VG Bild-Kunst/Artists Rights Society, New York City. Courtesy Sprüth Magers, Berlin and London

Writing a 9/11 novel from the point of view of a neuroscientist may be Doctorow’s way of saying that our politics are irrational, and that the failures of the Bush era were failures of thinking. Maybe. But reason can’t make sense of that handstand, which is an homage to Andrew’s second wife, former student, and true love, Briony, an exuberant gymnast who almost succeeded in getting him out of his head — until, that is, she went for a run downtown on the morning of 9/11. Since her death he hasn’t had much use for cognitive autonomy, with its burdensome memories, frustrated desires, illusory will, and countless griefs. He prefers to meditate on the power of “the communal brain.” Perhaps, he speculates, humans are governed by a shared mind, like an ant colony. “You know Emerson?” Andrew asks. “It’s what Emerson, thinking of his own kind of creature, mistakenly calls the oversoul. He romanticizes it, making it a constituent of ethical thinking suggesting God. When all he is aspiring to is a kind of universal pheromonal genius.”

Andrew’s Brain is erudite and humane and brisk, and almost overcomes its shticky setup. Andrew is a novelist’s kind of scientist, who turns for redemption to the familiar American pantheon: Twain, Emerson, William James, Walt Whitman. (The book ends with Andrew waxing plaintive about the stories Mark Twain told his children at bedtime.) Of course — and the author knows it — it was not Emerson but Thoreau who had the best lines about ants.

At the woodpile, on the chips, was where Henry David saw the only combat of his life, in the form of a red and a black ant battling. He quickly realized that “it was not a duellum, but a bellum, a war between two races of ants.” Republicans and imperialists, they fought to the death; he carried the specimens into the house he built and imprisoned them in a tumbler, and through a microscope he watched them eat each other’s legs, tear at each other’s feelers, and fight on, crippled, until “the black soldier had severed the heads of his foes from their bodies, and the still living heads were hanging on either side of him like ghastly trophies at his saddle-bow, still apparently as firmly fastened as ever.”

According to the geologist Robert M. Thorson’s Walden’s Shore: Henry David Thoreau and Nineteenth-Century Science (Harvard University Press, $29.95), those lines were written not by a transcendentalist or a philosopher but by a “competent, pioneering geoscientist” who read Charles Lyell and Charles Darwin more seriously than he read the Bhagavad Gita, and who taught himself not only botany but also watershed science, geology, and glaciology. Thorson’s passion often persuades, though his positivism has its own blindnesses, as in his distinction between “symbolic” truth and something he calls “actual” truth. His real target is not the general reader but the dreaded American Studies professor who teaches Thoreau as “literature.”

Thoreau’s journal entry on the cliffs at Fairhaven, for example, is the “smoking gun” that establishes his understanding of ice sheets: “It looks as if the snow and ice of the arctic world,” Thoreau wrote, “travelling like a glacier, had crept southward and overwhelmed and buried New England.” Poetry is redeemed by the extraction of empirical value. “Here,” Thorson writes, “the word ‘creep’ is not analogy, but the correct rheological term glaciologists use for the slow-but-steady, quasi-plastic, viscous flow of ice above a threshold basal shear stress.” (This is a typical passage; more than half of Walden’s Shore is geological history.)

There are interpretive gems, as when Thorson turns to the three lumps of undusted limestone that Thoreau threw out the window. This scene is often characterized as a tantrum against housekeeping (and housekeepers), but Thorson speculates that the rocks reminded the author of his failure, when building his house, to make his own lime — a lapse in his “Economy.” (Something of a housekeeper himself, Thorson admits to wanting to clean up the “mess” of trinkets and gifts that visitors leave on Thoreau’s grave.) Thorson casts himself as rescuer, saving Thoreau from those unable to penetrate the Journal’s observations, and from the poet’s own “intentionally unscientific reporting,” which buried its truths in jokes, innuendos, and ordinary language. He concludes that the captain of the huckleberry party “toggled” between poetic and scientific modes, though it’s hard to believe that Thoreau, who always imagined the earth as a living whole, thought himself a toggler.

Young Michael DeForge (b. 1987), a comer in the world of alternative comics, has given new life to Thoreau’s battle of the ants in his Web series Ant Comic, now collected and published under the title Ant Colony (Drawn & Quarterly, $21.95). True, Walden lacks gay members of the family Formicidae, and doesn’t contain any drawings of an owl-faced queen ant with giant yellow pear-shaped breasts tipped with pink-and-gray bull’s-eye nipples, with a cave between her legs that scores of speck-size males line up to enter, all the while complaining of the smell inside (“burnt rubber”). In Ant Colony, the black antiheroes are cowards, conscientious objectors, nihilists, children, and infertile females — noncombatants who quaver under psychedelic skies cruised by hippie bees. They are threatened by fierce (drunk on spider milk) red ants, who have breasts where a warrior’s breastplate would be.

It’s gross, absurd, and existential, and the storytelling is simple and bleak (DeForge describes his style as “really plain, dead lines, rigidly gridded pages”). He grants no victors and no spoils. The ants mistake an upside-down pyramid of pale yellow light for the fulfillment of a prophecy, but it’s just the sign that some human has come along and burned the battleground with a magnifying glass. At the end the survivors — an orphan tortured by visions, a female who may or may not be in a coma, a spurned lover, and a bozo of a cop — remain to rebuild the colony. Their efforts appear doomed. What can you do? As Andrew’s roommate learned, you go to war — or wars — with the army you have.

The red and the black: red for fire, black for night. Gaute Heivoll’s novel Before I Burn (Graywolf, $26) is the story of an arsonist who burned eight buildings in tiny Finsland, in the south of Norway, in the spring of 1978. Narrated in the present day by a writer who returns to the village to recover his own past, Before I Burn gives away the identity of the arsonist early on, with not even the hint of a red herring. The book was a bestseller in Norway, where it won the Brage Prize in 2010. Its power is not in who did it or even why, but in the brutal clarity of Heivoll’s unhurried and mesmerizing sentences, pushing through a chilly landscape like the steady shining of blue headlights.

Alma fixed her gaze on him. He seemed tired. His eyes were red and swollen. One eye was slightly smaller than the other. It went like that when he hadn’t slept. It shrank. He had been like that ever since he was a child.

Heivoll isn’t much for adverbs, but he has a palette. Red is for insomniac eyes, red-hot piano keys, a red pickup truck, a red-and-white sign that means stop, a red face, a red jacket, and red barns that crumble to “blackened wounds.” Black is for the black lake, black stump, black barrel, black figure, black bell, black forest, black beast, black chimney, and black ants. White is for the jerricans that spit the gasoline that started the fires that burned down the homes and barns. There was a car that drove away from the scene; maybe it was black or maybe red; it was too dark to say.

A kind of traumatized minimalism is in literary fashion, but Heivoll’s Nordic iciness and imagism blanket depths of feeling. Everything hinges on clean, spare descriptions of actions as ordinary as backing a car out of a driveway or eating a piece of toast. Each bit of plainspeaking picturing is on its own unremarkable, and yet the energy builds. His language is reduced, not amputated or stunned; it activates sensation instead of numbing it. I never did understand why fiction pretends to be about the mind.