Discussed in this essay:

Sherlock. PBS.

Elementary. CBS.

When does a fictional character cease to belong to the author who invented him? Last December, a federal judge in Chicago ruled that Sherlock Holmes, Dr. Watson, and their associates, foes, and accoutrements — including 221B Baker Street — are in the public domain in the United States. (They were already so in the United Kingdom.) The suit’s defendant, the estate of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, lost to Leslie S. Klinger, editor of The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, who persuaded the court that any elements from stories published before 1923 should be in the clear. “Sherlock Holmes belongs to the world,” the triumphant editor told the New York Times.

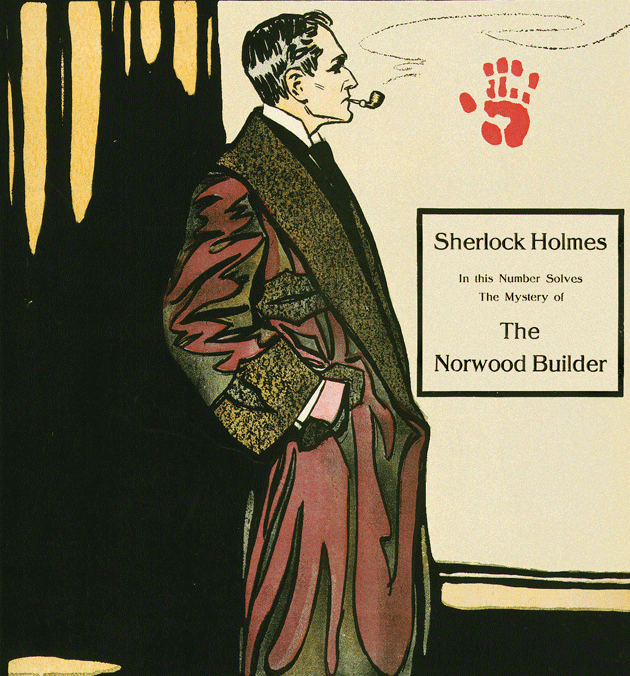

Illustration by Frederic Dorr Steele of “The Adventure of the Norwood Builder,” 1903,

from Collier’s © Eileen Tweedy/The Art Archive at Art Resource, New York City

Can there be any doubt that Klinger is right? The world’s greatest consulting detective is arguably the most popular fictional character of the modern era — adapted, staged, radio-dramatized, filmed, pastiched, parodied, comic-booked, video-gamed, and performed by countless actors, several of whom have seen their public image indelibly merged with the role. Two popular current television series, Sherlock (jointly produced by the BBC and PBS) and CBS’s Elementary, transpose the late-Victorian sleuth to contemporary settings. The blockbuster Warner Bros. film series — starring Robert Downey Jr. and directed by Guy Ritchie as a two-fisted, action-packed steampunk extravaganza — would probably, despite its period trappings, look nearly as alien to Conan Doyle as would the present-day imaginings of Holmes on the small screen.

This cornucopia does not delight everyone. In a pair of short essays for The New York Times Book Review, two critics, James Parker and Pankaj Mishra, were prompted to respond to the question “James Bond, Sherlock Holmes, Hercule Poirot: Why Do We Keep Resurrecting the Same Literary Characters?” Parker speculated that the “collective imagination” might be “caught in a diminishing loop of derivative creativity, some kind of stranglehold of the secondhand.” For his part, Mishra opined about the failure of the myriad Conan Doyle adaptations to engage “with the original myth of Holmes,” seeing the stories as, at heart, reassuring fantasies of the nineteenth century’s “ultrarational culture.” Take Holmes and Watson out of London in the 1890s and they lose their resonance, their local seasoning.

This cornucopia does not delight everyone. In a pair of short essays for The New York Times Book Review, two critics, James Parker and Pankaj Mishra, were prompted to respond to the question “James Bond, Sherlock Holmes, Hercule Poirot: Why Do We Keep Resurrecting the Same Literary Characters?” Parker speculated that the “collective imagination” might be “caught in a diminishing loop of derivative creativity, some kind of stranglehold of the secondhand.” For his part, Mishra opined about the failure of the myriad Conan Doyle adaptations to engage “with the original myth of Holmes,” seeing the stories as, at heart, reassuring fantasies of the nineteenth century’s “ultrarational culture.” Take Holmes and Watson out of London in the 1890s and they lose their resonance, their local seasoning.

But isn’t it the retelling that makes a myth? Classical myths and fairy tales have passed through many hands and have no discernible original; there’s no ur-version of, say, Orpheus or Cinderella, no pristine source without the fingerprints of Ovid or Charles Perrault (and who knows who else before them). Myths are stories that can be transformed significantly, depicted in any sort of medium, yet retain an identifiable essence. When Jean Cocteau made Orphée as a lush black-and-white French art film in 1950, it was still Orpheus, and he wasn’t called derivative or accused of resorting to cultural hand-me-downs. Creating new variations on classical motifs is not mere rebranding or rebooting; it’s one of the things great artists do.

Sherlock Holmes, of course, differs from Orpheus in that we remember where he came from, even as he mutates, disperses, and coalesces again and again, sometimes a drug addict and sometimes not (much), sometimes a master of disguise and sometimes not, sometimes celibate and sometimes, every so often, not. Occasionally, his reincarnations aren’t even detectives; television’s surly, pill-popping master diagnostician House was based on Holmes, who was in turn based on Joseph Bell, a lecturer at the medical school of the University of Edinburgh, for whom Conan Doyle, a physician himself, clerked. “I feel like . . . I see Sherlock everywhere . . . on almost every procedural,” Rob Doherty, the showrunner of Elementary, told a gathering of television critics in 2012. “Most shows have a Sherlock in them — they just happen to be called something else.”

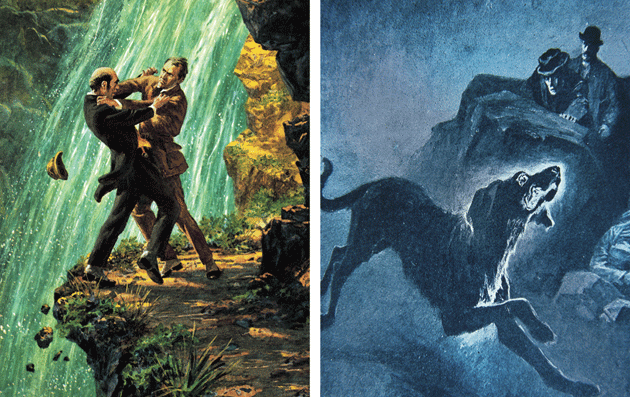

he Death of Sherlock Holmes © Private Collection/Look and Learn/The Bridgeman Art Library; illustration by Sidney Paget of The Hound of the Baskervilles, 1902 © John Meek/The Art Archive at Art Resource, New York City

The Sherlock myth began the moment Conan Doyle’s stories left his desk, though not with the inaugural Holmes novel, A Study in Scarlet, which aroused little interest when it was published in Beeton’s Christmas Annual in 1887. Holmes didn’t catch on with the public until Conan Doyle’s short stories about his adventures were serialized in The Strand Magazine in 1891. That’s when the collaborating began. It was an illustrator, Sidney Paget, who gave the detective his deerstalker, headgear now completely identified with the great detective but never once mentioned in Conan Doyle’s fiction. The calabash pipe came nearly a decade later, adopted by William Gillette, a beetle-browed American stage actor who personified Holmes in the United States and Britain for thirty-three years. (“I would rather see you play Sherlock Holmes than be a child again on Christmas morning,” the novelist Booth Tarkington once wrote to the actor.) Gillette found the curve of the pipe easier to talk over, and unlike the straighter-stemmed shapes it didn’t block the audience’s view of his face.

Conan Doyle didn’t mind any of these embellishments, mostly because he didn’t care all that much for his creation. Gillette, who also wrote Sherlock Holmes, the play in which he performed the lead, once cabled Conan Doyle to ask if it would be all right to give Holmes a love interest. “Marry him, murder him, or do what you like with him,” was the author’s response. In his fond short biography, On Conan Doyle; or, The Whole Art of Storytelling, the critic Michael Dirda marvels at how as early as 1891 Conan Doyle began planning to kill off the detective so he could get around to worthier projects, namely historical novels. “The best literary work,” Conan Doyle informed one interviewer in 1910,

is that which leaves the reader better for having read it. Now nobody can possibly be the better — in the high sense in which I mean it — for reading Sherlock Holmes, although he may have passed a pleasant hour in doing so. It was not to my mind high work, and no detective work ever can be, apart from the fact that all work dealing with criminal matters is a cheap way of rousing the interest of the reader.

Conan Doyle made Holmes plunge to his death at the bottom of Reichenbach Falls in 1893, with the publication of “The Final Problem.” To send the detective off with sufficient moment, the author concocted an archenemy who had not previously been mentioned, the diabolical Professor Moriarty, who grappled with Holmes and tumbled with him down into the abyss. But public demand for more tales remained high, and in 1903 Conan Doyle relented, producing “The Adventure of the Empty House,” in which Holmes reappears, explaining to Watson that he has spent the intervening years assisting Eastern potentates and conducting “research into the coal-tar derivatives.”

Conan Doyle continued to write Sherlock Holmes stories into the 1920s. In the five decades after that, the figure most readily identified with the great detective would be the actor Basil Rathbone, whose hawklike profile and suave voice represented Holmes in films and radio beginning in 1939. Of the fourteen movies in which Rathbone played Holmes, twelve transpose the detective to a contemporary setting, where his remarkable skills are employed in fighting the Nazis. But Rathbone’s Holmes is very much Conan Doyle’s Holmes, a man who, apart from a few foibles and eccentricities, fits reasonably well into the mold of the late-Victorian hero, or for that matter of the mid-twentieth-century Saturday-afternoon-matinee hero. Holmes may show no interest in romantic love and may affectionately scold Watson for his “fatal habit of looking at everything from the point of view of a story instead of as a scientific exercise,” but he has a finely attuned moral sense and the emotions that come with that. In “The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton,” Holmes describes his “repulsion” at the titular blackmailer with an “intensity of feeling” that impresses Watson:

[H]ow could one compare the ruffian, who in hot blood bludgeons his mate, with this man, who methodically and at his leisure tortures the soul and wrings the nerves in order to add to his already swollen money-bags?

The great detective’s independence from his author grew in the 1930s with the formation of Sherlock Holmes societies, such as New York City’s Baker Street Irregulars, of which both Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman were honorary members. The most storied of these groups are what came to be known as Sherlockians, producers of mock scholarship that treated Holmes, Watson, and company as historical rather than fictional figures. This activity, known as “the great game,” found fodder in the many gaps, contradictions, and inconsistencies in Conan Doyle’s tales (typically referred to among Sherlockians as “the Canon”). Dr. Watson’s war wound, to name the most conspicuous example, is sometimes said by Conan Doyle to be in his shoulder, sometimes in his leg. It’s unclear how many times Watson was married, when, and to whom. In “The Adventure of the Empty House,” the memory of Professor James Moriarty is defended after his death by his brother — Colonel James Moriarty.

The great game involved not only devising preposterous explanations for these gaffes but also concocting scenarios extending beyond the margins of Conan Doyle’s invention, such as arguing that the American author Rex Stout’s fictional detective Nero Wolfe is the son of Irene Adler (“the woman” in the Canon) and either Sherlock or his brother, Mycroft. According to Dirda, a member of the Baker Street Irregulars, Sherlockians have at various times presented learned treatises demonstrating that either Watson, Holmes, or Moriarty was a woman.

The Sherlockians were the first manifestation of what is now known as fandom. Fans, of course, predate Sherlock Holmes, even if they weren’t always called by that name, but fandom is something more. Fandom moves past simply cataloguing and discussing beloved source material and engages in a wide range of related creative enterprises: amateur illustration, theorizing about the undisclosed backstories of characters and events, designing and wearing costumes, and writing fan fiction. Early Holmes fans wrote parodies and pastiches — among the best known is Bret Harte’s “The Stolen Cigar-Case,” which has a fawning narrator awestruck by the ability of “Hemlock Jones” to deduce that it’s raining — but their faux scholarship, especially when it aimed to expand and elaborate the imagined world of Sherlock Holmes, is also a sort of proto–fan fiction.

Fan cultures tend to thrive in the cracks of works like the Holmes stories — sweeping enough to suggest an entire landscape to explore, but full of suggestive lacunae and subtexts. Conan Doyle’s lackadaisical quality control, paired with the ineffable brio with which he enlivened the devices of pulp adventure, created an ideal growth medium. At times, the Holmes stories seem to beg for extrapolation; one of the most familiar and delicious Holmesian tropes is the passing reference to a sensational-sounding case that cannot, for some reason, be put before the public. The best example of this is “the giant rat of Sumatra, a story for which the world is not yet prepared,” but other tantalizing passages allude to “the colossal schemes of Baron Maupertuis” and “Ricoletti of the club-foot and his abominable wife.” Anyone more familiar with the post–Conan Doyle Holmes is likely to be both startled and disappointed to learn how briefly and perfunctorily characters such as Irene Adler, Mycroft Holmes, and Professor Moriarty appear in the Canon. All three grew considerably in adaptations and retellings, but only because the few tidbits of information about them supplied by Conan Doyle whetted the imaginative appetites of his fans.

Edmund Wilson, who loved Sherlock Holmes stories despite his general contempt for detective fiction, wrote, “the writing, of course, is full of clichés, but these clichés are dealt out with a ring that gives them a kind of value,” and “over the whole epic there hangs an air of irresponsible comedy, like that of some father’s rigmarole for children.” It is central to the pleasure of the Sherlock Holmes stories that they invite play, and that they were never meant to be taken seriously, either for the dastardly criminals whose designs provide the great detective with his cases or for the order restored to a snow-globe version of London once the cases are solved.

Nevertheless, a time comes when even lightly held verities demand to be challenged, and the Holmes stories have shown the peculiar elasticity of myth, allowing themselves to be reshaped along with the needs and preoccupations of the day. This began in earnest with that decade of doubt, the 1970s. Nicholas Meyer’s novel The Seven-Per-Cent Solution: Being a Reprint from the Reminiscences of John H. Watson, M.D. appeared in 1974 — the year Patty Hearst was kidnapped and Richard Nixon resigned the presidency — quickly becoming a bestseller and, two years later, a popular film. Meyer’s Sherlockian premise elaborates the background behind Watson’s claim, in “The Adventure of the Missing Three-Quarter,” to have “gradually weaned” Holmes of using cocaine (and occasionally morphine). In the Canon, Watson, who regards Holmes’s drug use as “his only vice,” makes clear that his friend resorts to cocaine out of boredom. But Meyer, writing in an age of therapy, has the doctor arrive at a more advanced diagnosis: repression.

Whereas Conan Doyle’s Holmes ties his self-medication to his mind’s being “like a racing engine, tearing itself to pieces because it is not connected up to the work for which it is built,” Meyer’s Watson has come to believe that Holmes, a “deeply passionate human being,” turns to drugs, among other outlets, to relieve some mysterious “emotional stress” pent up behind the detective’s serenely analytic surface. After Meyer’s Holmes appears at the doctor’s door in the grip of drug-induced paranoia, Watson, aided by Mycroft, persuades him to travel to Vienna and seek treatment from Sigmund Freud, who conquered his own addiction to cocaine and who ultimately uncovers the childhood trauma responsible for Holmes’s behavior.

The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, with its clever parallels between psychoanalysis and detection and its seamless integration of historical and fictional figures, is great fun. It also marks the arrival of a new view of Sherlock Holmes. The personality traits that once singled him out as a heroic genius came to be seen as signs of pathology. In a lesser-known but nearly as striking novel from around the same time, The Last Sherlock Holmes Story, by Michael Dibdin, Holmes enlists Watson in his pursuit of the one real-life criminal whose notoriety rivals the fame of the fictional sleuth: Jack the Ripper. Like The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, Dibdin’s narrative asserts that the two Conan Doyle stories depicting Holmes’s faked death are deceptions cloaking a much darker truth. In The Last Sherlock Holmes Story, Watson discovers that Moriarty is an alter ego of the psychologically disintegrating Holmes and the perpetrator of the Ripper murders.

Holmes never fully recovered the uncomplicated gallantry of the Basil Rathbone years. The actor most aficionados consider to be the quintessential postwar Holmes, Jeremy Brett, who played the detective in a series for Granada Television in the 1980s, portrayed him as a creature prone to odd tics and mercurial moods. Brett, who was manic-depressive, identified with similar tendencies in Conan Doyle’s Holmes, described repeatedly by Watson as alternating between fits of exhilarated energy and periods when “for days on end he would lie upon the sofa in the sitting-room, hardly uttering a word or moving a muscle from morning to night.”

Even when he wasn’t being depicted as Janus-faced — half detective, half murderer — the late-twentieth-century Holmes was often made to stand in for the inadequacies or bad conscience of an instrumentalist and materialist philosophy equated with the scientific method. In two literary novels of the 2000s, Mitch Cullin’s A Slight Trick of the Mind (soon to be a film starring Ian McKellen) and Michael Chabon’s The Final Solution: A Story of Detection, a very elderly Holmes — retired, as he always planned, to beekeeping in Sussex — is forced to confront the sinister side of the worldview he once championed. In the first novel he surveys the wreckage of Hiroshima, and in the second he faces the horror of the Nazis’ eminently systematic and rationalized death camps.

In the most recent incarnations of Holmes, the detective is regarded by most of the people in his immediate circle, even himself, as patently dysfunctional and perhaps even dangerously so. Suspicious and resentful police detectives in the BBC’s Sherlock speculate openly about the likelihood that he’ll turn to crime, and they address him as “psychopath”; to one of these antagonists Benedict Cumberbatch’s Holmes acidly retorts, “I’m not a psychopath, Anderson, I’m a high-functioning sociopath. Do your research.” The Holmes played by Jonny Lee Miller in CBS’s Elementary is an antisocial recovering addict sent to New York City by his wealthy father, who hires a former physician, Joan Watson (Lucy Liu), to live with him as his “sober companion.” Her job is to provide counseling that will prevent him from relapsing. Holmes’s psychological problems are less emphasized in the Guy Ritchie films, partly because action movies are themselves a rather sociopathic genre. Even so, Jude Law’s Watson watches the often buffoonish antics of Robert Downey Jr.’s Holmes with almost unceasing exasperation and alarm.

Sherlock is the most stylish and inventive of the recent Holmes adaptations, one in constant and witty dialogue with the Canon. (Mark Gatiss, creator of the show with Steven Moffat, is a keen Holmes buff who also plays Mycroft in the series.) Sherlock makes a fascinating effort to represent Holmes’s thought processes visually; overlays of text and image illustrate the way the detective reads the objects of the physical world or riffles through his vast storehouse of memories. This is a Holmes who, unlike Meyer’s, cannot be “cured” because his problems are not psychological but neurological; his brain simply works differently from everybody else’s. Watson suggests Asperger’s syndrome, a diagnosis (until the most recent edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which replaced it with autism spectrum disorder) characterized by lack of empathy, obsessive interests, and, occasionally, savantism.

Meyer’s Holmes needed Watson to get him into therapy, but the Holmes of both Sherlock and Elementary needs Watson to teach him how to interact with the everyday world and cultivate his humanity. (In the first episode of Sherlock, Holmes scoffs at the idea that a dying woman’s last thoughts would be of her dead child, exclaiming, “That was ages ago! Why would she still be upset?” Seeing the shocked face of the Scotland Yard detective, he turns to Watson and asks anxiously, “Not good?”) The friendship between these two characters, always one of the great charms of Conan Doyle’s stories, has become the heart of the new adaptations. In Elementary, Watson enters the narrative with the sole purpose of helping Holmes live a normal life, and even after she becomes drawn into detection as his apprentice, she is forever urging him to tone down his abrasive manner and counseling him on how to work more harmoniously with the police. “There is not a warmer, kinder me waiting to be coaxed out into the light,” he warns her at one point.

I am acerbic. I can be cruel. It’s who I am, right to the bottom. . . . And in my work, my nature has been an advantage far more often than it has been a hindrance. I’m not going to change.

The hope and belief that Watson’s loyalty, warmth, and decency can get Holmes to change pervades both Sherlock and Elementary. Along with that hope comes renewed speculation about the nature of their relationship. Jokes about a homoerotic romance between Holmes and Watson go way back. The suggestion even features in the 1970 Billy Wilder film The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, in which Holmes fends off the advances of a Russian ballerina by leading her to believe (untruly) that he and Watson are lovers. Fantasies about canonically heterosexual male characters falling in love with each other have also been a staple of fan fiction since the early 1970s, when female Star Trek fans began to write stories about romance blossoming between Captain Kirk and Mr. Spock (whose adherence to logic and rejection of human emotions resembles Holmes’s rationalist credo). In an interview about Sherlock, Steven Moffat told the Hollywood Reporter:

It’s got such a huge female following . . . this massively exciting, rather handsome man who could see right through your heart and have no interest . . . of course, he’s going to be a sex god! . . . I think our female fan base all believe that they’ll be the one to melt that glacier. They’re all wrong, nothing will melt that glacier.

Holmes has always had female fans (among the most prominent was the detective novelist Dorothy L. Sayers), but whereas the original’s focus on boyish adventures with a minimum discussion of feelings tends to appeal to the yearnings of men, Sherlock lavishes its attention on the relationships and emotions that typically speak to women. The first episode of Season 3, for example, dwells almost entirely on John’s reaction to learning that Sherlock faked his own death; the second deals with Sherlock’s (mostly inept) efforts to serve as best man at John’s wedding. Conan Doyle’s Watson was uncomplicatedly delighted to learn that his friend was still alive, while Sherlock’s John (the greater intimacy of the BBC series seems to demand use of characters’ first names) is hurt and enraged at having been deceived and made to suffer the pain of grieving Sherlock for two years. The thriller element of the story, even though it involves a load of bombs placed under the Palace of Westminster, really just serves as background to the reconciliation of the two men. Sherlock’s best-man toast, initially sidetracked by his explication of a case, ultimately resolves into an admission that the detective is “a ridiculous man” who is “redeemed only by the warmth and constancy” of his friendship with “the bravest and kindest and wisest human being I have ever had the good fortune of knowing” — words that mirror the canonical Watson’s eulogizing of Holmes: “the best and wisest man whom I have ever known.”

With Sherlock especially, the heightened emphasis on the bond between Sherlock and John has spawned a fervent admiration among Chinese audiences, who have viewed episodes from the first season online more than 24 million times. While on a visit to China last December, the British prime minister, David Cameron, fielded questions from the public via a social-networking site, and according to the Daily Telegraph, “by far the most popular request was: ‘Please urge the Sherlock crew to be quick! They have had us waiting for two years for every season!’ ” A robust culture of fan fiction flourishes there too, specializing in torrid embraces and tender romance between Sherlock and John, whom the Chinese public have nicknamed Curly Fu and Peanut.

It’s a long road from the blithe vanity of Conan Doyle’s Holmes to a man willing to describe himself as “ridiculous.” But Benedict Cumberbatch’s Sherlock Holmes is still recognizably the character who appeared in the pages of The Strand Magazine in 1891, and even the hardcore Sherlockians of the Baker Street Irregulars embrace the new series. Is the quality that makes Holmes Holmes his Britishness or his late-Victorian attitudes? His rationality or his suppressed emotions? His crime-fighting, his addiction, his love for John Watson, his ability to read and interpret the language of the dumb objects of the world? Perhaps future generations will choose to highlight some other facet of the great detective; for it seems that his most defining characteristic is his talent for being simultaneously so versatile and so abiding.