Many comedians consider stand-up the purest form of comedy; Doug Stanhope considers it the freest. “Once you do stand-up, it spoils you for everything else,” he says. “You’re the director, performer, and producer.” Unlike most of his peers, however, Stanhope has designed his career around exploring that freedom, which means choosing a life on the road. Perhaps this is why, although he is extremely ambitious, prolific, and one of the best stand-ups performing, so many Americans haven’t heard of him. Many comedians approach the road as a means to an end: a way to develop their skills, start booking bigger venues, and, if they’re lucky, get themselves airlifted to Hollywood. But life isn’t happening on a sit-com set or a sketch show — at least not the life that has interested Stanhope. He isn’t waiting to be invited to the party; indeed, he’s been hosting his own party for years.

Because of the present comedy boom, civilians are starting to hear about Doug Stanhope from other comedians like Ricky Gervais, Sarah Silverman, and Louis CK. But Stanhope has been building a devoted fan base for the past two decades, largely by word of mouth. On tour, he prefers the unencumbered arrival and the quick exit: cheap motels where you can pull the van up to the door of the room and park. He’s especially pleased if there’s an on-site bar, which increases the odds of hearing a good story from the sort of person who tends to drink away the afternoon in the depressed cities where he performs. Stanhope’s America isn’t the one still yammering on about its potential or struggling with losing hope. For the most part, hope is gone. On Word of Mouth, his 2002 album, he says, “America may be the best country, but that’s like being the prettiest Denny’s waitress. Just because you’re the best doesn’t make you good.”

Stanhope prefers seedy and neglected venues in part because those who seek him out there have some idea of what they are buying into, which is an intimate act that’s at once intellectually acute and graphically foul. Since 1999, when he first performed “The Transvestite Hooker Incident,” Stanhope has been telling true stories about his real-life adventures, which include tales of sex wagers, abortion, and getting fired. “It felt a little ballsy at the time,” he recalls, to be making money off what someone else would consider his “worst, horrific, closeted embarrassment.” Stanhope’s many CDs and DVDs chronicle his ongoing evolution in the rousing company of some of America’s more alienated citizenry. Recorded in places like the Velveeta Room, in Austin, Texas, or Dante’s Inferno, in Portland, Oregon, the titles give you a sense of Stanhope’s preoccupations: Something to Take the Edge Off, Deadbeat Hero, Burning the Bridge to Nowhere, and Before Turning the Gun on Himself. “Fetish comedy” is sometimes how he describes his type of material. At other times, “Comedy that leaves a stain.”

Stanhope takes responsibility for where he’s been and where he’s going, and he’d like for the rest of us to do the same. An avid proponent of population control, he refers to abortion as “green” and sodomy as “eco-friendly.” He also defends the right to die: “Life is like animal porn — it’s not for everyone.” He wants people to realize they are always making choices, even in their passivity. When his fans complain about their lousy hometowns — as they regularly do — he reminds them, “You can leave.”

Whether despite or because of the darkness of Stanhope’s material, once people arrive at an evening he’s hosting, they often don’t want to go home. An egalitarian ethos infuses his shows. Everyone is welcome — especially those who are unwelcome elsewhere. (Once he crossed the street to avoid a riot as he arrived for a show, only to discover that the mob was made up of his fans.) He dresses for the occasion — lately quite becomingly in pastel thrift-store polyester suits, like a Vegas showman. He refers to people he recognizes in the audience by name, drinks the shots you send him, and usually won’t smoke onstage if you can’t smoke on the floor. He hangs around after the set if the mood is right, to see whatever might happen. “What you didn’t do is never funny,” he reminds his fans, many of whom try to live by his credo — at least for the one night he’s in town.

Stanhope maintains this spirit of radical hospitality on his website, where his entries serve as a postmortem for the gatherings and as a teaser for whatever is coming up next. This is also where he expresses solidarity with beginning comics, inventories his body’s decline, and suggests pranks to keep himself and his core fans, the “sausage army,” amused.

Doug Stanhope’s Celebrity Death Pool, which was inspired by Fantasy Football, is a signature maneuver. “Mourners” join competing “funeral homes” and make their top twenty picks of those celebrities most likely to die in the coming year. The tally is calculated using a formula of 100-points-minus-the-age-of-the-dead-celebrity, with various bonuses for the cause of death: “The Kurt Cobain” for suicide; “The Amy Winehouse” for accidental death by drugs or alcohol; “The John Lennon”; et cetera. Like so much of what Stanhope does, the CDP appears cheap and vulgar while making a political statement. If we are going to comb over the dietary and exercise habits of celebrities the same way bettors follow the training regimens of purebred horses, the CDP suggests, we should get something out of it — some consciousness about our monstrous illusions, perhaps, or at least a laugh or two.

There are no subjects Stanhope won’t approach, and death is a perennial favorite. Beer Hall Putsch, his 2013 album, includes a powerful story about euthanasia called “Farewell, Mother.” He’s currently working up material on a close friend’s suicide. The CDP makes death into entertainment, and — unlike Fantasy Football — “the season never ends.” Recently, he invited fans to bet on his own head (“It’d be a pretty good solid choice, just based on the lifestyle”), a sly nod to his growing popularity and a characteristically preemptive strike: The game of life is rigged and we should all grab whatever fun is available. Stanhope has joked that he wants you had to be there engraved on his tombstone.

When Doug Stanhope began his Big Stink Tour, in 2012, he had just returned from an overproduced seven-week run in the United Kingdom, playing to half-empty theaters and riding in an unnecessarily large touring bus. He wanted to get back to the basics with his carefully chosen comrades — his girlfriend, Amy “Bingo” Bingaman; his road manager, Greg Chaille; and his two handpicked openers, Carlos Valencia and Junior Stopka, whom he referred to as “the children.” “Old-school,” Stanhope told me excitedly, “in a van, like we used to do, driving around and telling butt-fuck jokes.”

I caught up with the crew that August in Tampa, Florida. Before the first night was over, I was already worried about going the distance. I made my bid for physical moderation at four a.m. in Stanhope’s suite at the Hilton Garden Inn, after we’d closed down a local bar, the children had been poured into the comedy condo, and Bingo had passed out in the bedroom. Even the indefatigable Chaille — who was once a manager at the biggest bar in Anchorage, Alaska — had been sent to bed. Stanhope was still drinking when he invited me to continue the conversation downstairs so he could have another cigarette. He laid out his reasoning for his hard-driving lifestyle with the practiced charm of someone who’d encountered pleas like mine before. He explained how sober Doug structured the bits and worked out the material’s logic; drunk Doug found the funny, refined it onstage, and pursued whatever chaos ensued from the gig. We went back upstairs and he poured another drink. “I’m a comedy team,” he said teasingly. “I am the comedy team of Doug Stanhope — morning and night. One of ’em wouldn’t work without the other.”

The lines between work and play in Stanhope’s life were frequently invisible, yet I had to concede he was an utter professional; he never missed a morning radio spot and he never threw a set in the trash. Whereas some comics use the same jokes for years — even decades — he consistently comes up with hours of new material. And he is a practiced host. As night gave way to morning and the early edition of USA Today thumped against the door of the hotel suite, I realized I wasn’t sure which Doug I was talking to: the seeker who lived fully in the moment or the pro who took care of business, which involved taking care of me along with everyone else.

Stanhope was the first up the next morning, and we pulled out of the parking lot before ten, with Chaille, the only one Stanhope will let drive, at the wheel. Valencia was riding shotgun and manning the radio; behind them, Stopka nursed a hangover beside his girlfriend, Maggie Ednie, who is also a comic, and who had no memory of meeting me the night before. Stanhope and I were in the third row of seats, and Bingo was asleep in the back of the van. The companionable quiet was not only due to the hangovers — it was a happy peace.

On the road, we listened to three comedy podcasts. Stanhope was mentioned admiringly in each. No one talked on their phones or texted much or talked much at all. So it was startling when, an hour outside Valdosta, Georgia, Stanhope’s phone rang: Phyllis Diller had died.

I assumed, because Diller was a comedian, that the caller was passing on bad news. But after Stanhope hung up, he immediately called his CDP team’s scorekeeper. “Somebody must have had her,” he said excitedly. “Diller,” he continued, getting impatient. “Like the pickle! Phyllis Diller! The old comedian lady — somebody must have her.” At the moment, Stanhope held second place in the CDP and Bingo was in third. In February she’d moved up with Whitney Houston as a solo pick.

It was dusk when we arrived at the Valdosta Days Inn, a grim spot tucked just below the interstate where the tour would spend a night off. In the parking lot, a very large biker was cleaning an immaculate and very large motorcycle. The tractor-trailers rumbled past. In the near distance, a billboard with the advertisement strippers: need we say more? as seen on jerry springer. I wondered aloud about the prospect of going for a jog — in terms of safety. The liquor store, across the street from the ransacked convenience store, was heavily barred. The attached lounge where Stanhope had planned to spend the evening was closed, and he was already recalibrating for us both.

“Do you want a sleeping aid to help you get through this?” he asked cheerfully. He had a few extra Xanax. “Not a place where you want to be up all night. Or ever.”

To make the best of the long evening, we all ended up in Stanhope’s room, where we watched Intervention. The children taunted the woman on the screen, and Ednie, who was sitting close to the TV, kept saying, “This is my life” and “This is me.” Meanwhile, Stanhope composed tweets about watching Intervention while drinking. (“There’s no such thing as addiction,” he has said. “There’s only things you enjoy doing more than life.”)

For years, Dr. Drew, the host of Celebrity Rehab, was one of Stanhope’s principal targets. In a 2011 nine-minute bit called “Dr. Drew Is to Medicine What David Blaine Is to Science,” Stanhope attacked the doctor’s selective empathy: “You would step over a dozen dying winos in the street just to get to Lindsay Lohan’s bedside to offer unsolicited advice.” He compared Dr. Drew to a gynecologist who says, “Teenage Norwegian pussy is all I really work with anymore, because I want to give back.”

By the time the night wound down, Ednie could have used some help making her way to her room. Stopka was emptying already empty liquor bottles like a scavenging bear. Valencia had gone to bed and Stanhope and Chaille were snoozing on their lumpy mattresses. Bingo was the only one upright, singing along to music on her old CD player in the open doorway.

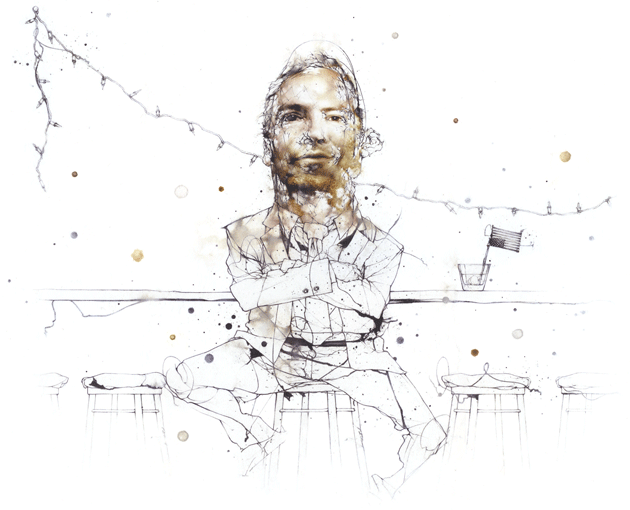

Stanhope’s shows sometimes have the quality of a reunion, which was exactly the feeling the following night on an industrial road in Pensacola, at a dump called The Handlebar. Strings of dust hung from the pipes like dull tinsel, but the friendly crowd was getting lit. Longtime fans had turned out to hear the latest installment of Stanhope’s exploits.

I was talking to Justin Otto, a blues musician, whom I’d met at our motel, where his girlfriend is the bartender and Stanhope had been drinking that afternoon. Both of them came to see the show. Earlier Otto had been eager and admiring; now he greeted Stanhope with contempt — “You’ve got a fuckin’ entourage!” — as if shocked by the fact that Stanhope wasn’t just like him after all. Stanhope ignored him. He expects nothing better from his audiences. Audiences are fickle.

Before he went on, Stanhope listened to the local opener, who was apparently working out his divorce rage. Stanhope gives every new comic a few lines to earn his attention, but this guy would need years before he sounded like whoever he was. When Stanhope finally stepped up onto the cluttered stage, he asked the people in the front to sit on the floor so the people standing in the back could see. He shook his head slowly as he took a sip of his drink — a brief pause, so everyone could take stock of the mess they were in. Otto’s girlfriend started recording Stanhope with her phone. “Becka!” he said, as if trying to shake her into reality. “It’s me! We were just drinking together! Put that down! I’m right here!”

Master comedians are always operating on multiple levels. Stanhope’s evolving relationship with his fans, and their stake in his unfolding story, add another satisfying dimension to his freewheeling shows. That evening, at The Handlebar, he started with a bit about being on tour and needing to rest before going onstage; it was also about the terms of the exchange at the heart of the industry he is in. He set the scene: He was in a hotel, in need of a nap, but it was too close to showtime to take a pill. He thought masturbating would help him sleep, but he didn’t have his laptop.

“Have you ever tried to jerk off without the Internet? I know I used to do it,” he said. “I used to use a pay phone too, but if you made me use one now, I’d be confused for a minute” — he tapped the pockets of his pink leisure suit looking for change. He found the hotel’s pay-per-view offerings equally baffling, he said: “Sexy Co-eds . . . Big Boob Bonanza — what is this, starter porn for children?” His needs weren’t pretty. The audience laughed; they understood the road to ugly, too.

When Stanhope finally settled on a movie starring Chyna, a former WWF wrestler, the audience moaned in recognition. “Nothing about Chyna was built for pornography,” Stanhope said. There was clapping and hooting.

A daring comic might earn the ability to close with a bit that’s both complicated and raunchy; Stanhope can open with one in part because his audiences know the terrain. But entertainers still have to give a good show, which in Stanhope’s case means giving his fans more of himself. He paused before serving up the movie’s title — Backdoor to Chyna — then he waited for the laugh before needling them again. “I was jerking off for you, the audience,” he reminded them. Then he described pulling out his paper and pen: “That’s when you know you’re too wrapped up in your career, when you try to multitask a yank.” But he honored his part of the deal and went all the way for them — reporting in detail his findings about the “ripple-backed she-ogre,” her “refried tit job,” the broken body “all scar tissue and nipples askew.” The bit was not only about porn and its consumption but also about what was going on right that minute between him and the crowd at The Handlebar. The audience members groaned as if they were being punched.

Although Stanhope is a steadfast opponent of vice laws, he confessed that even he was taken aback: “All the feminist arguments against pornography? That it’s humiliating and degrading to women? In this case, I’d have to admit they were true!” The mischief made his dewy eyes appear improbably cute.

Watching the former wrestling champion ambushed and sodomized while julienning vegetables wasn’t enough, Stanhope continued: he had to see her register how she’d fallen, too. “I just waited to see the look in her face where I thought she had plummeted to the rock-bottom golf divot of anything she’s done in her life,” he said, his mortified pleasure at Chyna’s humiliation a mirror held up to the crowd. But when he growled, “Yeahhh! Take it in the ass, Chyna!” it wasn’t clear whether the performer or the viewer was getting screwed. “Take it, Chyna!” he said, acting out the pathetic ejaculation that would have been impossible without her. “Yeahhhh! Welcome to show business!”

After he dropped out of high school his sophomore year, Stanhope made his way to Las Vegas, where he became an outstandingly successful telemarketer. He would entertain his colleagues with material he’d memorized from the albums of Andrew Dice Clay. When he left telemarketing to pursue comedy full-time, he spent three years living out of his car, taking whatever gigs he could get. Stage time is the only way for stand-ups to sharpen their skills, and he developed quickly as a comedian.

Unless a headliner is a recognized name-draw, comedygoers often attend shows without much knowledge of who is performing. When Stanhope began headlining comedy clubs in the late Nineties, he would occasionally “walk” some of the audience (offended customers would leave). Comics normally work five-show runs, Thursday through Saturday. Rather than play to five half-full rooms, Stanhope realized it would be more fun and lucrative to do a single show for people who’d chosen to be there. He began to collect the email addresses of audience members who stayed. Then he’d send out offers to perform wherever people would gather, and his fans would suggest possible venues and help him arrange gigs at rock clubs and bars.

Comedians usually compete to lay claim to the latest news event, to see who can come up with the highest-quality funny, but in the weeks after 9/11, many of Stanhope’s colleagues held back in public. Not Stanhope. “America is a bloated celebrity who doesn’t feel it has to pay the cover charge,” he told audiences. The power of great stand-up is in the moment, and Stanhope’s political interests made this moment irresistibly ripe. (“Drugs support terrorism?” he asked rhetorically. “No, it’s your fucking SUV.”) He needed to get onstage whenever and wherever he could: “Does anyone get upset that George Bush keeps quoting the Bible in all his fucking speeches?” he said in one bit from the period. “Does it ever occur to him that it’s all those stupid fucking religions that start all this shit in the first place? National Day of Prayer? Fuck you! You think you’re doing something? You’re not. . . . You wanna pray? Pray all day. Pray on your own time. You wanna help, grab a shovel and start digging there, pinwheel, ’cause it looks like your god takes Tuesdays off.” The combination of calamity and inspiration made it a wildly creative time for him. “It’ll never be that good again,” Stanhope says now.

Another comic mentioned Stanhope’s work to Brian Hennigan, who produced shows at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. Stanhope’s performance there won the 2002 Strathmore Press Award. The validation — from bona fide comedy critics — gave Stanhope name recognition in the United Kingdom and launched his touring career there.

In 2003 and 2004, he co-hosted The Man Show on Comedy Central after Jimmy Kimmel and Adam Carolla moved on to more civilized things. For most performers, more success means less accountability to the rank and file, but Stanhope went in the opposite direction. When The Man Show aired, he advised his new fans to catch up by buying his CDs and encouraged them to read You Are Being Lied To, a guide to “media distortion, historical whitewashes, and cultural myths,” with articles by Noam Chomsky and Howard Zinn. He posted this on his website:

The first few episodes . . . are going to be the weak shit, so live with it. There’ll be weak shit periodically throughout, don’t get me wrong, but they front-loaded the beginning of the season with the most mediocre stuff, thinking that the hardcore Jimmy ’n Adam audience is too fucking dumb to handle the stuff we like. Maybe they are. The first time we said the word “abortion” you could hear the crowd’s ass-pussies lock up like an emergency brake. Same with bashing religion, or much of anything that didn’t involve jacking off or shitting your pants.

Stanhope was a perfect Man Show host — he was quick-witted, he was attractive, he drank, talked like a pig, and acted gross — but he was also up to something, and he knew it couldn’t really happen on TV.

People keep congratulating me and saying “It’s about time,” as though this is better than what I was doing. It isn’t. The only true freedom of speech anymore is stand-up and anything else I do is just to promote it.

Stanhope hates big cities, but even he can’t resist New Orleans. Fans were lined up around the block for his sold-out show at a place called One Eyed Jacks. The refurbished theater had a velvety bordello vibe, and there were bars everywhere — at the entrance, tucked up in the balcony, on the floor leading to the main stage. Chaille had stocked the bar in the dressing room for the performers, and the children were riding high from Bourbon Street, excited to perform for the packed theater. Thrilled to be included, the local opener declined a drink — he was in recovery. But the evening was pulling hard in another direction, and he’d fallen off the wagon by the time Stanhope took the stage.

It was still the beginning of the tour, but Stanhope had already hit his stride. His pleasure fueled the momentum of the show. “It’s autopilot now,” said Chaille happily as he paused beside me on his way to replenish the dressing-room bar. “In the course of three weeks he’s pieced together an entire hour.” The next album was taking shape. Stanhope’s stories, rather than sounding self-contained and needing bridges to connect them, felt like organic parts of a whole. The bits now had multiple ways into the other material, and the performance flowed like a free conversation. Stanhope was way over time — a good sign — when he ran into his NFL closer.

This starts off with his irritation with breast-cancer-awareness campaigns intruding on Sunday football — his favorite form of escapism. But the pink ribbons are just the premise for exposing the homoeroticism in the sport. “You have eleven men bent up in a huddle,” he said. “Beautiful, thick man-ass — it creates a Bangkok whorehouse situation in your head.”

“Faggot!” someone yelled out. This was exactly the resistance Stanhope was hoping for. He drew it out: “Big, sinewy haunches, they are talking to ya!” “You’re a fucking faggot!” someone else chimed in. The riff he’d been trying out against homophobia — how at every opportunity, we should all claim to be gay — was now irresistible. Stanhope gleefully delivered it. By the time he was finished, he’d stripped away not only the trappings of conventional masculinity but also white fear of black male sexuality, denial of death, and what our national lust for oblivion costs us — ending on the global gravestone of AIDS.

“You suck!” someone yelled, but more of the room was laughing, trying to stay with him. Plenty of people looked confused. Some seemed stunned. Others were laughing so hard, or were so drunk, that they couldn’t keep their eyes on him. Two young men standing just below Stanhope had been trying to pass him drinks all night. Now they seemed as bereft as their empties, which lined the edge of the stage.

By the end of the nearly three-hour show, the audience looked exhausted, but Stanhope invited everyone at One Eyed Jacks to come along with the Big Stink to see Bingo’s musician ex-boyfriend perform. But first, he closed out. He had a celebratory drink backstage with the children, then he hung out with fans for almost an hour, taking pictures and signing what was left of the merchandise. After that, he counseled a depressed local comic on the street, in a doorway. Then he corralled everyone into a cab to Le Bon Temps Roulé to hear the Brass-A-Holics — Bingo’s ex’s jazz-funk band. Outside the club, a young woman who said she was an MFA student was still giddy from the NFL bit. “How did you know that?” she asked Stanhope excitedly. “You are in my dreams! I will never deny that I anally sodomize football players in my dreams!”

It was morning by the time we were standing outside our hotel, considering the next move. Bingo, who had danced through the night, plopped on the curb, her knees up to her ears, her blue pigtails drooping. Stanhope and Stopka were entertaining each other with jokes about trading us in for a better group of chicks — more specifically, the ones who were teetering by on heels or zigzagging past on bicycles. The whole city was drunk.

For Stanhope, this was often when things might just begin to get interesting. I announced that I was going to bed.

“Okay, honey doll,” he said. “Let us know about the scoop you catch at the Continental breakfast.”

In 2011, Stanhope received a handwritten letter from a man named Liam S. V. Hughes:

Dear Doug . . . or should I say feloow drunk Doug,

I was at your show last October or November down in Ft Lauderdale, I was the creepy kid in black among the crowd of creepy kids in black and I really enjoyed the show and I’m glad I got to see you live because I was beginning to think you weren’t real; I was starting to think you were some form of CGI digital Santa Claus that was sent down by God to save us from this retarded society we live in. At least I got to see the philosopher Doug Stanhope do his magic and I’m talking real magic, the kind that makes you want to drink even when you really don’t want to.

Anyway, since you’re reading this you should know that I’m already dead by the time you get this. I’m no fan of the world and even less the way I live in it, and there are some good things but I’ve had 23 almost 24 years to do those things, and although I want to stay a little longer and get to see some more I can’t, for the moral justice thinks I have to do 7 years in a prison for looking at the wrong kind of porn even though that happened to me as a kid and I never complained about it.

Anyway, now that I’m completely out of hope, I’m leaving you my favorite book, which I think you will like and maybe give a few ideas for new material. It’s not perfect but most of the concepts in the book are similar to your views, just a little less vulgar.

So Doug, thanks for giving me something to laugh at, that was almost impossible with my gloomy outlook and sick sense of humour.

Thanks for being the one person with the balls to speak out the truth. I hope you are much more successful in what’s left of your career and save some worthy people before it’s too late.

Thanks and good luck

Your fan and follower.

Liam S. V. HughesOh and by the way, it’s painless helium suicide in case you were wondering. At least I DIED LAUGHING!

Even an unusually brave comedian might not consider a handwritten note from a suicidal consumer of child porn something to broadcast. But for Stanhope, reports from our fellow travelers are never unwelcome — no matter how painful or revolting or sad. His job is to make something of them.

Stanhope eventually posted Hughes’s letter on his website, explaining that he’d verified the suicide and adding that Hughes’s reasoning had been sound. The young man’s prospects in prison would have been grim, considering his crime. Then Stanhope mused on his own relationship with his constituents:

Comics always say that they are happy to be able to make people laugh, to give em a small break from their daily grind, their grueling nine-to-five. A lot of my people have a much darker grind and I’m happy to give them a nice chuckle and release at the end of a long day setting fires, drowning their kids in a car and blaming it on the blacks or debating between suicide or prison.

Liam Hughes was certainly not the only really fucked-up fan I’ve had nor will he be the last. I don’t know exactly why I appeal to so many wrecked, scared, miserable, ugly, angry or otherwise ill-suited for life as we know it. But I’m not unhappy that you’re here. Every time there’s somebody like the Aurora theater shooter, I check my mailing list and Facebook to see if they were a fan. I know that if it weren’t for comedy, I might be sitting in a dark room stockpiling weapons and putting names on lists.

Maybe you should try writing jokes. Or kick-boxing or something. Join a Neighborhood Watch. That’s where all the real psychopaths hang out.

I don’t have all the answers. I just do comedy.

But in the meantime, certainly keep your cards and letters coming to 212 Van Dyke St. Bisbee AZ 85603.

The Relapse Theatre in Atlanta seemed to hold the past and future of Doug Stanhope’s career. The venue was sold out; the stage was bigger than he preferred; the air-conditioning was broken. The once grand building felt as if it were being occupied by squatters who’d meant to rebuild the place but just ended up hanging around. People were friendly, but no one was in charge. It may have been the late light of the end of summer, but there was a sense of both nostalgia and promise in the moment.

Stanhope’s fans were a mix of the new guard and the old. Some members of the black-T-shirted sausage army had just learned that they should have bought advance tickets and were brooding. There were elderly Swiss academics who’d discovered him on the Internet and office workers who’d heard him on satellite radio and new converts from his appearance on Louie and a solid smattering of hipsters. There were women — not the usual dragged-along girlfriends or dates unknowingly being subjected to Stanhope as a relationship litmus test, but women on their own and with their female friends. The majority of those I spoke to said they’d been attracted by his abortion jokes.

Grant Lamberson, a musician, came because Stanhope’s name kept cropping up everywhere. “I get offended,” he said, preparing himself. “I can get over it.” A woman named Jennifer Brown liked his bit about a friend who had breast cancer, but she’d bought a ticket after hearing him chastise Daniel Tosh for apologizing for a rape joke he’d made. She thought it was ridiculous to make comedians apologize for anything. Some had learned about him through his comments about Ron Paul, others through his writing about police brutality. A man named Ricky Wilburn told me — and I believed him — “I never come out unless Doug’s in town.”

It was the last gig of the first leg of the Big Stink tour. After a short break at his home in Bisbee, Stanhope would start up again in the fall with new openers. He loved those openers too, but this Big Stink crew had been perfect. They decided to go out in the spirit that had carried them this far, and they wore polyester prom suits Stanhope had bought them. They were blue and red and white, and oversize and silly, and they came with matching shoes and shirts. Junior Stopka was all in red, and Carlos Valencia called it: he looked like a menstruating giant’s used tampon.

At the venue, the young woman at the ticket counter tried to stop them, until Chaille informed her that they were the talent. “Sorry! How embarrassing!” she yelled as the Big Stink crew disappeared downstairs.

The temperature kept rising. Someone propped open a door and the ticketless trickled in. There was no assigned seating and no security, so there was no way to tell who belonged there and who didn’t. When the show started, Chaille, alarmed that the local emcee was shouting, went off to hunt for a working microphone.

The theater was packed — about 650 people. They stood along the walls in the back, spilling sixteen deep into the lobby. The waitresses had to navigate their way around the people on the aisle floor to deliver drinks. There was a visceral feeling of camaraderie. When Stanhope came onstage, it took some time for the applause to wind down.

He looked awful. His thinning hair was wet with sweat, and his pale skin looked corpselike — especially under the amateurish lighting, against the cheesy white suit. “I’m going to try to get through this without fucking fainting,” he said. He took a few steps in his vinyl fuchsia shoes and looked over the kind of democracy he’d assembled. He promised to stay with them, because they were all going down. “I busted the air-conditioning on purpose,” he said with a smile. One of the fans sitting in the front row looked like a grandmother — she must have been in her seventies. “We’ll get through it,” he promised her, before turning to address the rest of the crowd: “It’s the last night of the tour and I want someone to fucking die.” His voice was hoarse. People hooted. “But,” he continued, deploying his subterranean charm. “But I paint on a fucking smile and take it in the ass.” He paused. The cheering started again. “Like you will,” he added. The audience was ready.

He told us that he’d been thinking about the limitations of comedy — its tendency to only inventory problems. He wanted to do something, or at least come up with some solution-oriented material. He did Chyna and a fantastic bit on the Occupy movement — suggesting they take some strategy tips from Scientology. His subjects went from low to high, “smut and socially relevant,” he noted, adding that if it were easier to find people who wanted both, “I’d have a way bigger audience and we’d be in a place with air-conditioning.”

By the time Stanhope moved into his NFL riff, the room was fully with him. The audience felt like a single entity. His middle-aged, self-hating Sunday-football fanatic was suddenly streaking across the field in his imagination: “Your dick’s slapping against your belly — you’re wearing nothing but one of those 1800s nightcaps with a pom-pom, and flip-flops,” he said. “It’s your fantasy. Make your dick as large as you want.”

Stanhope was giggling — at what he was up to, or his own ridiculousness, or ours — as he talked about activism and escapism, lust and hatred, passivity and agency, with the kind of originality and ease that looks like casual conversation but that in fact has been paid for in the hundreds of thousands of miles he’s traveled over the past twenty-three years.

The logic was intricate and the language was brutal as he began to act out the sodomy, slowing down for each gory violation as he thrust his pelvis forward and back, forward and back. He looked as surprised as we did at what he was doing. The laughter came in rolls, like an unending wave that kept promising to crest. One woman was screaming. At the moment the bit usually met with a resounding “Faggot!” or “Faggot, die!” — all Stanhope got was laughter. Stanhope’s own chuckling broke into a horrid cough.

He looked so small from where I sat in the back — just a guy onstage in a cheap polyester suit, his balding head shining with sweat in the glaring lights, trying to give his crowd the fun they needed by giving over whatever he had left in himself.

Stanhope thinks that comedy is the biggest con of all — getting paid to make people laugh. He wishes people would make their own fun with their actual friends, but then he’d be out of a job. The faces all around me in the Relapse Theatre were intensely awake and alert. Some looked as though they were watching a horror movie or a roadside wreck, unable to turn away. Others looked more and more childlike. Guys were doubled over, unable to stop laughing. One put his hands over his ears. People were rocking and slapping their friends’ backs and their own legs. One young man kept leaning into his girlfriend, helpless, and she was laughing just as hard at the sight of him unable to collect himself.

You had to be there. And, for better and for worse, Stanhope did as well.