Discussed in this essay:

To Rise Again at a Decent Hour, by Joshua Ferris. Little, Brown. 352 pages. $26.

Among the many impressive things about Then We Came to the End, Joshua Ferris’s first novel, was the coolly assured way it matched form to content. Most debuts (most novels, in fact) fumble uncertainly toward the right method for displaying their particular goods, but Ferris seemed to know in advance exactly how to tell his bittersweet tale of life and death in a Chicago advertising office. An epigraph from Emerson, stating that the worst thing that can happen to a human being is “not to be reckoned one character . . . but to be reckoned in the gross, in the hundred, or the thousand,” underpinned the key narrative decision: to have an anonymous narrator tell the story in the first-person plural. This spectral presence — a kind of collective office ego — rendered the characters slightly flattened, slightly smaller than life, which neatly supported Ferris’s central insight into the infantilizing effect of corporate culture on its personnel. It also gave just the right edge of humor to the anecdotes of cubicle life that formed the bulk of the novel, making even the most studiedly low-key among them feel momentous. Add to this Ferris’s unexpected and very touching sympathy with the objects of his satire, and the book’s enormous success begins to seem not only deserved but inevitable. It delivered the white-collar soul, in all its dimly comprehended anguish, its wistful resignation to its own tameness, as wittily and poignantly as anything I’ve seen in recent years.

The stylized but essentially realist approach of that book was stretched toward a more fabulist mode in the follow-up, The Unnamed. That story features another corporate man rattling his cage, only this time not through the scrupulously plausible rebellions of the earlier book but through strange periodic urges to go off on long walks around the suburbs of New York City and beyond, striding unstoppably until he passes out.

The Unnamed was disappointing. Having set up his walkabout concept, Ferris never seemed sure what kind of novel to build around it. Should the compulsive walking be treated as a metaphor for man’s thwarted nomadic nature, like something out of Kafka? Or might it work better as the initiating device in a Jekyll-and-Hyde story (the protagonist, a lawyer, is investigating a murder)? Was its quasi-fantastical aspect best left unexplained — the premise for a DeLilloesque novel of feverish rhapsodies and reveries on our apocalyptic times? Or should it play out as a literal-minded medical thriller with the familiar cast of head-scratching doctors and long-suffering family members?

At different moments the book tries out each of these possible versions of itself. The result reminded me of an experience I once had, working on a script (also about a corporate guy in crisis) for a Hollywood production company, where every week the director and I would get “notes” from a different executive — make it more mythic, more realistic, more of a thriller, more of a love story, funnier, sadder, beef up the family, make him more lonely, and so on. In our eagerness to please them all (they’d paid us a lot of money) we ended up with a garble of narrative scar tissue that in due course became a train wreck of a movie. That’s what happens when you’re not as gripped by an idea as you’d hoped to be, and instead of working it from the inside you try to steer it by second-guessing your audience.

The most visible symptom of things coming unstuck in The Unnamed was an increasingly obvious forcing of effects. The prose in Then We Came to the End was steady and functional, but even its most humdrum scene-setting passages had a fine-grained gleam, like brushed steel, that was very appealing:

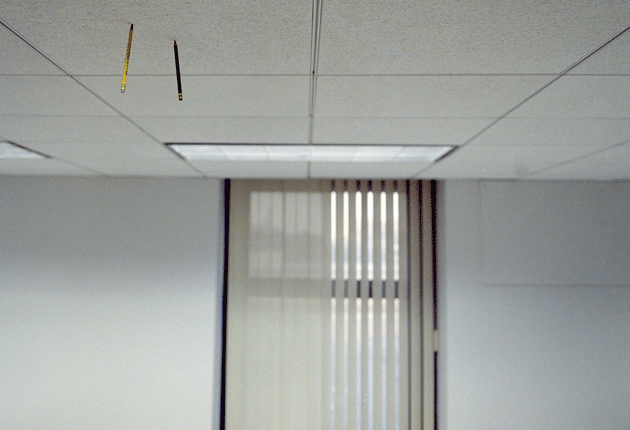

We had wide hallways. Some contained offices running along both sides, while others had offices on one side and cubicles on the other. Jim Jackers’ cubicle was unique in that it was set off in a corner. He had a wonderful view because of that location and we questioned whether he deserved it. To get there you had to walk past the toner stain in the carpet on sixty. He shared that prime space with one other person, a woman named Tanya something who worked on a different partner’s team. A retractable wall separated them, made of thick privacy glass, the kind used in shower windows. Behind it, one moved about, it seemed to the other, as if scrubbing and deodorizing, when really they were just filing or inputting.

The writing in The Unnamed feels so pumped up in comparison that at one point I wondered whether Ferris wasn’t signaling the reader, over his publisher’s shoulder, that he’d lost interest in the project:

In the past he could sleep anywhere, in the snares of frostbite and the hothouses of heatstroke, exposed to ticks, spiders, snakes, the insult of birds, the menace of authorities and of the evil intentions of men.

The decision one night to sleep on the side of the road had forced him into the back of a squad car and his God talk and end-of-days ranting combined with some old-fashioned disrespect ended him up in the psych ward under physical restraint. He was given a more effective cocktail of anti-psychotics and forced to take it, daily, until his release, upon which time the importance of finding seclusion and protection for himself became intuitive again.

It’s hard to believe that the author of that first passage — so plain and yet so confidently itself, with its glint of subtle mischief — wouldn’t know that the second was at once overwrought and perfunctory.

Second novels are supposed to stumble, and one would think a writer as talented and idiosyncratic as Ferris would dust himself off pretty quickly and realize he didn’t need to be Kafka or DeLillo or anyone else. I certainly came to the new one, To Rise Again at a Decent Hour, with high expectations, though I should say that I also had some rather personal, non-literary reasons to be curious about the book.

It tells the story of a dentist named Paul O’Rourke, who becomes the target of a campaign of online stalking and identity theft that seems, as it progresses, to be motivated by a general fixation on Judaism, and a particular obsession with the connections between anti-Semitism and the behavior of Jews toward their enemies, from biblical times to the present day.

I was recently the target of an uncannily similar campaign, with similarly menacing emails, similarly embarrassing online postings in my name, and a similar underlying obsession with Jews, particularly in their hoary double role as the world’s victims and oppressors. “No more about the 6 million,” writes O’Rourke’s stalker, “until OUR losses and OUR suffering and OUR history have finally been acknowledged.” Mine wrote: “jews in america need to shut up. the crazy shit that comes out of your mouths spreads far and wide in a city filled with blacks, muslims and asians who’ve had it.” O’Rourke goes to Israel in an attempt to make sense of his strange ordeal. I did the same.

In the end there isn’t much to be said about these coincidences except that they confirm a feeling of mine that Judaism and Israel are no longer cultural or geographic phenomena so much as regions of the human brain, like Wernicke’s area or the hippocampus, where some pervasive psychoses get processed. Given the Internet’s propensity for encouraging every kind of lunacy, one can see why a novelist interested in the stresses of modern life might want to set a story on the porous borderland where these two territories — cyberspace and the Middle East — meet.

O’Rourke, as his name suggests, isn’t Jewish by birth, but he certainly is by inclination. He has enthusiastically embraced the rituals of Jewish family life that surround Connie Plotz, his ex-girlfriend and current receptionist. “I wanted to be a Jewish Plotz,” he declares, “who sat shiva and went to shul and made babies with Connie behind the bulwark of safety that was the Plotz extended family.” Only his staunch atheism has kept him from actually converting, though the Plotzes are more concerned by the whiff of something dodgy in his apparent philo-Semitism. As he himself guilelessly puts it: “I was always paranoid that I might be saying something anti-Semitic.” Earlier in life he had created a similar situation with a Catholic girlfriend, an episode that ended with his loitering menacingly outside her home.

Given the congruities between the dentist and his stalker — the shared fixation on Judaism, O’Rourke’s own borderline stalking behavior — one half expects the book to turn into another doppelgänger story, especially when it transpires that the mystery antagonist happens to know some rather private things about O’Rourke.

The book does develop a doppelgänger theme, though like The Unnamed it pursues it distractedly, while trying to do all sorts of other things at the same time, among them a Pynchonesque alternative history, with real and invented arcana mingling like the Thurn und Taxis and Trystero postal systems in The Crying of Lot 49. As the cyberstalking continues, O’Rourke finds himself drawn into a conspiracy involving some pseudobiblical writings that purport to tell the secret history of the marginalized Ulm people, fictitious descendants of the biblical Amalekites, who were nearly wiped out in a war against King David and the Israelites. A long history of genocidal oppression, mainly at the hands of the Jews, qualifies these Ulms (at least in their own eyes) for the designation “the Jew’s Jew.” They practice a religion based on doubt, and have come to believe that O’Rourke is one of them. And indeed, as he investigates the source of his troubles, he seems to close in, Oedipus-like (or Oedipa-like, if you prefer the Pynchon), on himself.

What to make of these curious propositions? Even with the echoes of my own experience, I found it hard to figure out what Ferris was after here — what the story beneath the story was, so to speak. Sporadic allusions to the Palestinians suggest a possible intent to comment on contemporary Middle Eastern politics, which in turn raises the question of whether O’Rourke’s dark secret is just a desire to violate some taboo, or perceived taboo, against criticizing Israel or Judaism itself. But if that’s the case, Ferris loses his focus (or his nerve) before he gets very far, retreating into elaborations of his “counterhistory” of the Ulms. Their story unfolds through a series of meetings between O’Rourke and various types familiar from this kind of quest — the dusty antiquarian, the publicity-shy billionaire, the elusive cult leader. The ultimate aim of this plot strand, or one of them, seems to be to confront O’Rourke with the Ulms’ latter-day prophet, a certain Grant Arthur, who turns out to be essentially a repetition of O’Rourke himself. Like O’Rourke he was once in love with a Jewish girl and obsessed with “as he put it ‘all those rituals and prayers and things’ Jewish people were always doing.” And like O’Rourke his romance was thwarted by his atheism. It’s a bizarrely specialized quandary to build a novel around, and to have not one but two characters trapped in it feels like an attempt to make a case for it as somehow a representative paradox or pathology. But representative of what?

The fine novelistic intelligence of the first book, in which all the thinking about the comedy and tragedy of human life was done through pure story — tightly focused and patiently constructed — has given way to something looser, talkier, more freewheeling in To Rise Again at a Decent Hour. I understand the desire to move in this direction — who wouldn’t want to be more freewheeling? But looseness and talkiness just aren’t what Ferris is good at. By the end of the book I wondered whether the real subject he was wrestling with, via O’Rourke’s Judeomania (that seems to be the only word for it, finally), was an anxiety about measuring up to the great Jewish novelists of recent decades. Saul Bellow’s exuberant intellectuality, Philip Roth’s transgressive comic routines, the effortless way in which both writers move between action and commentary, story and meditation: these are the effects Ferris seems to be striving for in To Rise Again. He clearly wants his protagonist to be seen as a great noticer of things, and as a great monologuist too (both already a tricky match with this kookily sophomoric dentist whose idea of being clever is to call Europe “Eurpoe” and iPhones “me-machines”). To that end he has O’Rourke sound off at regular intervals about social networking, celebrity culture, moisturizer, the fortunes of the Red Sox, and other markers of contemporary life. Once in a while he does actually reach beyond the obvious into something like wit — for instance, the suggestion that churches ought to look and smell more like Pottery Barn if they want congregations — but you notice these moments only because they are rare. A good riff (tired word, but maybe the rhetorical effect it refers to is getting a little tired, too) comes out of overabundance. It requires sufficient mastery of voice, attitude, subject, and context for the performer to shift into a realm of pure play. It isn’t enough just to take aim and blather. O’Rourke has nothing particularly interesting to say about most of his subjects, but he says it anyway. At best the result is a weird sort of low-grade observational muzak. At worst it’s just filler. Here he is on celebrities:

How many celebrity couples I’d known and how out of date all of them had become! For the people now following Daughn and Taylor, Bruce and Demi were an ancient artifact of the 1980s. The 1980s were thirty years ago. The people now following Daughn and Taylor thought of the 1980s as I used to think of the 1950s. The 1980s had, overnight, become the 1950s. It was unimaginable.

On shoppers at malls:

There they were, with their lists and missions, their handbags and gift cards, moving with oblivion in and out of the stores. A mall can make you feel alive again if you go there only to watch and if you watch without judgment, looking kindly upon the concerted shoppers, who have no choice about buying or not buying, it would seem, and who would not want that choice — not if it meant no longer knowing what to want.

Humor resists analysis, and not everyone reacts to the same joke the same way. There’s one narrative tic in the new novel that seems intended to be humorous, but it drove me nuts. It’s a game Ferris plays with dialogue, repeatedly omitting O’Rourke’s side of a conversation so that the reader is compelled to figure out what he said:

She’d sniff at me like a bloodhound and then she’d say, “What exactly have you been doing?” I’d tell her, and she’d say, “Why do you feel the need to lie to me?” I’d tell her, and she’d say, “Scrutiny does not kill people. Smoking kills people. What kind of example do you think you’re setting for your patients by sneaking off to smoke cigarettes?” I’d tell her, she’d say, “They do not need a reminder of ‘the futility of it all’ from their dental professional. When did you take up smoking again?” I’d tell her, she’d say, “Oh, for heaven’s sake. Then why did you tell everyone you quit?”

Why don’t I find that repetition funny? After all, there was a repeated phrase in the first book — “walking Spanish down the hall,” the employees’ preferred term for being fired — that made me chuckle every time I read it. Is it simply a matter of taste, disposition, prejudice? Am I just on the wrong wavelength here? It’s entirely possible.

But it’s also possible that I’d be more generous in my reactions if the book was more generous in its efforts to provoke them. For all its complications, To Rise Again at a Decent Hour strikes me, in the end, as a complacent novel — an exercise in pushing buttons rather than articulating fully imagined ideas, characters, and situations.

Then We Came to the End embodied its author’s ambivalent feelings about corporate life in a cast of plausible yet highly original figures. Here we don’t get characters at all, just caricatures and stereotypes (the Jewish and Catholic families of the former girlfriends are unabashedly that), or, as in the case of O’Rourke himself, such a confusion of attitudes, personal idioms, and emotional reflexes that they become indecipherable. Big subjects — doubt, belief, identity, the Middle East, the Internet — are announced but never explored in any depth. Doubt especially — which seems to be what the book is touting as the grail at the end of O’Rourke’s quest, a corrective to both his atheism and the too-certain faith of others — remains just a word, devoid of any living imaginative tissue. Ferris doesn’t have a viable language, comic or serious, for dealing with the mysteries he wants to confront. Instead he veers between breathless agonizing —

“Okay,” she said. “I’m just going to say it. Remember how I told you that I was a nonpracticing atheist? Well, I’m not, really. I mean, I sort of was for a while, but now I think I’m not. An atheist, I mean. What I mean is, I’m not a hundred percent certain that God doesn’t exist, and sometimes, I’m almost certain that He does.”

“As in, you believe?” I said. “You’re a believer?”

“Sometimes, yes.”

I was shocked.

“Sometimes?”

“Most of the time.”

I was beside myself. On how many occasions had she expressed her skepticism about God?

— and tonal effects, such as the following biblical/surfer hybrid, that are just too daffy to add up to anything at all:

Oh, and everyone needs to get circumcised. And everyone’s like “Circumcised? What’s circumcised?” And the young Israelite-looking guy tells them what it means, and they’re all like “Jesus Christ, are you kidding?” And the Israelite-looking guy says he wishes. So all the men circumcise themselves, and they send messengers to the tribes of Israel to tell them what they’ve done, and they pray to the God of the Israelites that they be spared the sword.

The peculiar frictionlessness of the book reminded me of a passage in Kafka’s diaries in which he talks about the sensation of writing meretriciously, something he apparently felt he was doing quite often. He offers the image of a man standing in front of two holes. Only the hole on the right can bring forth the truthful visions the man is waiting for, but that hole remains stubbornly inert. Meanwhile false visions rise effortlessly out of the one on the left, distracting him and growing so large they finally hide the other hole altogether. I couldn’t help thinking of that as I read this gifted writer’s dismaying misfires. You’re looking in the wrong place, I wanted to tell him. Stop and wait for things to clear, then try again.