Discussed in this essay:

The Brunist Day of Wrath, by Robert Coover. Dzanc Books. 1,100 pages. $30.

One evening in December 1951, a coal mine in southern Illinois combusted and collapsed. An observer later remarked that it looked as if a bomb had been dropped into a subway. A chance spark or cigarette had lit a pocket of marsh gas, and fire flooded the mine’s vasculature, splintering timbers, overturning heavy machinery, and bending steel rails into fishhooks. The men closest to the blast were carbonized. Those farther away felt only a warm wind and an uncomfortable pressure in their ears as the tunnels went black.

The Orient No. 2 explosion was the deadliest the country had seen in decades. Some 120 men were entombed. Within hours the blocked tunnels began filling with carbon monoxide; rescuers recalled the sight of pigeons roosting in the mine’s elevator shaft dropping dead. The trapped men curtained themselves off from the gas (a technique called bratticing) and awaited rescue, but many knew it would not come in time. They wrote farewell notes to their families on cigarette packages, cough-drop boxes, whatever they could find. (“I love you all way. I go tonight with Christ. I love Him too.”) A group of about a dozen men poured water on the dirt and buried their heads in it, hoping to escape the gas.

After three days of rescue efforts, all those inside the mine were presumed dead. Then, on Christmas Eve, 550 feet underground, rescue workers wearing gas masks found a survivor lying among the dead. His name was Cecil Sanders, a sickly and by all reports pious man. From his hospital bed, Sanders sang “Amazing Grace” for a national radio audience. He told reporters that “nobody but God had anything to do” with his rescue, which he called “a miracle.” (Doctors speculated that his many years spent in the mine had gradually accustomed his body to the gas.)

A few miles away, the junior high school basketball court was converted into a morgue. Bodies were brought in and laid out on the floor to be identified. Blood seeped into the wood; the smell was “terrific,” remembered one witness. A nineteen-year-old reporter named Robert Coover, dressed in a sweatshirt and jeans, sat in the bleachers taking notes. Home from college on break, he had agreed to help out the paper his father managed, the Herrin Daily Journal, which was short-staffed. His assignment was to transcribe the names of the dead.

Every great writer, it seems, has a formative horror. For some it is a war, an illness, an abuse, an abandonment, a death. For Coover it was an explosion. The scrabbling for meaning that followed the disaster — the rumors, the prayer vigils, the journalists picking over the wreckage — gave him a riddle he has spent his career unraveling: How are myths made, and how can they be unmade?

Coover’s first novel, The Origin of the Brunists, published in 1966, centered on the lone survivor of a coal-mining disaster. It established Coover’s reputation as an author of gritty and ambitious social-realist novels. Coover once told an interviewer for The Antioch Review that he wrote The Origin in a conventional style “thinking that it might be the last piece of my writing read by a general public.” His true passion lay in composing the crumbly, self-aware novels and short stories that would later be labeled metafiction. The Origin was meant to be his Meet The Beatles!, a sacrifice laid at the feet of the American marketplace before he could drop acid and make Sgt. Pepper’s.

The book was not a bestseller, but it garnered critical praise. John Gardner — who would later call Coover a “closet fascist” on account of his fervent (but decidedly unfascistic) insistence that truth is constructed and relative — deemed The Origin “brilliant” and “superb.” The William Faulkner Foundation agreed, giving Coover its 1966 award for best first novel, which Thomas Pynchon and Cormac McCarthy had won in preceding years.

“The strength of this novel derives from the old traditions,” wrote Webster Schott in the New York Times. “It brings us the news about mining, petty journalism, small-town nonculture and the weird fusion of truth and wish that sometimes underpins religious belief.” Schott predicted: “If he can somehow control his Hollywood giganticism and focus his vision of life, he may become heir to Dreiser or Lewis.”

In the nineteen books that followed, Coover made a mockery of this advice. His subsequent work was brilliantly unfocused and antirealist. And in contrast to the ice-flat nouveaux romans coming out of France, Coover’s novels were feverish, lewd, and most of all funny. According to the novelist Hari Kunzru, Coover

broke open the carapace of postwar American realism to reveal a fantastical funhouse of narrative possibilities. His relentless experimentalism, combined with a sly and often bawdy humour, have made him a writer’s writer, a hero to those who feel smothered by the marshmallowy welter of pseudo-literary romance that dominates contemporary fiction.

In April, Coover surprised his readers once again, by publishing a sequel to his first novel. It marks a return not only to the mining town where he grew up but also to the traditional style he long ago abandoned.

Robert Lowell Coover grew up in the I section of the national bookshelf: Iowa, Indiana, and Illinois. His grandfather was a traveling Methodist preacher, his father a choir director. As an adolescent, Coover awoke to the existence of godlessness only when, one Sunday, a man sitting next to him in church refused to take communion. He asked the man why. The man responded: “Oh, I don’t believe any of this stuff. I just come here because I like to sing.”

Coover’s agnosticism slowly crystalized into atheism as he floated through one college and the next, trying his hand at zoology and psychology before finally graduating from Indiana University with a degree in Slavic studies. He enlisted in the Navy to avoid being drafted into the Korean War, and was sent to Germany, where he worked in cryptography. His mission was to transcribe and decode Soviet radio messages. It was hopeless work: the codes were mechanically set and automatically shifted every day, making for months of Hellerian absurdity. Instead of transcribing the intercepted messages, bored officers would sometimes listen to country music and simply jot down letters at random.

In the library of his naval base in Bremerhaven, Coover discovered the four horsemen of postmodern fiction — Beckett, Borges, Cervantes, and Kafka — and resolved to become a writer. In order to get started, he went to live alone on an island on a lake in Canada. (He would later write a short story for this magazine, called “Beginnings,” that began: “In order to get started, he went to live alone on an island and shot himself.” Tom Wolfe would cite that line as the epitome of all that was wrong with contemporary fiction.) Among Coover’s scant belongings were a Bible and a pile of Beckett, which he read from Genesis to Revelation, Murphy to Molloy. He chose his reading list carefully. Two distinct questions gnawed at him. The first was the paradox of biblical belief — its pervasiveness despite its apparent falsifiability. The second was how to write a new kind of fiction. To him, these problems were inextricable.

Though he was no longer a believer, Coover found the Bible’s mythic residue, as he would later come to call it, impervious to rational argument; it had wormed down too deep into the language and the culture. Drawing on the philosopher Karl Jaspers’s assertion that myth must be confronted on myth’s own ground, Coover began prying at Christian lore from within. In Beckett he had found a new voice, fractured and absurd, which he began using to rewrite biblical narratives. He wrote a story about the Flood told from the perspective of Noah’s brother, who is cruelly left behind as the waters rise.

I’m figurin maybe I got a day left if the rain keeps comin and it don’t show no signs of stoppin and I can’t see my brother’s boat no more gone just water how how did he know? that bastard . . .

He wrote another about a profoundly sexually frustrated Joseph, who dies in a tavern when a laugh curdles into “a fit of consumptive coughing.” In “Beginnings,” the protagonist begins (but presumably never finishes) a story about Lazarus

in which Jesus, having had the dead man dragged from the tomb and unwrapped, couldn’t seem to get the hang of bringing him around. There was an awful stink, the Jews crowding around were getting sick, and Jesus, sweating, was saying: Heh heh, bear with me, folks! Won’t be a minute! If I can just get it started, the rest’ll come easy!

The first of Coover’s stories to be published, however, was one he’d penned years earlier, as an undergraduate at Indiana University, called “Blackdamp.” It describes a coal-mining disaster as witnessed by a woman whose boorish husband is trapped inside. Coover sent the story off to Saul Bellow’s new literary magazine, The Noble Savage. It was published in the fourth issue. Encouraged, he sent the editors some of his more experimental stories. Bellow and his co-editors rejected them, finding them “sensationalist” and lacking in the “human content of art.” Other editors had a similar reaction; Coover was asked repeatedly whether he had another story like that one about the coal mine.

“So I began to invent one,” Coover later told an interviewer, “and that’s how The Origin of the Brunists was born.”

The Origin of the Brunists is set in the Midwestern town of West Condon. One day in January, the local coal mine blows up. The high school gym is converted into a temporary morgue. A newspaperman collects the names of the dead. He regards the scene — “black bodies, burnt and gas bloated” — with unblinking clarity. A woman asks the attendants to remove the shoe of one of the corpses, to check whether it has a corn plaster like the one she applied to her husband’s foot before his shift:

The shoeless foot stuck out screaming nude on the end of the black leg, a blistery glowing pink vegetable thing attached to the charred leg stump like a mushroom. There was a corn plaster too, but the woman didn’t think it was the same kind.

The disaster spares only one miner: Giovanni Bruno, who is found alive but catatonic. The free indirect perspective jumps from character to character, but the narrative is never filtered through Bruno’s consciousness; he forms the novel’s hollow core. Around his bedside gather a motley group of zealots, each interpreting the miracle of his survival in a different way. One, the widow of a Nazarene preacher who died in the mine, believes her husband’s garbled farewell letter — “I dissobayed and I know I must Die. Listen allways to the Holy Spirit in your Harts Abide in Grace. We will stand Together befor Our Lord the 8th of . . . ” — is a prophecy. Another claims to receive messages from an extradimensional being named Domiron. A third is a numerologist who scans the papers for omens. Their belief systems cross-pollinate, and the loose cluster of followers clots into a cult. When Bruno awakes and begins making gnomic pronouncements, his followers, the titular Brunists, interpret his mumbling to foretell a looming rapture.

A book as sprawling and multifaceted as this cannot be said to have a proper protagonist; or, as the novelist Brian Evenson has pointed out, the town of West Condon is the protagonist. But just as The Wire refracts our outrage at Baltimore’s corruption through Jimmy McNulty, the reader sees West Condon through Justin “Tiger” Miller, who callously deceives the Brunists in order to infiltrate their ranks. Miller, a former local basketball star turned newspaper editor, has a mind like Hume and a libido like Hef. For him, journalism, like sex, is all the more fun because its rules are so easily bent:

Once a day, six days a week and sometimes seven, year in, year out, the affairs of West Condon were compressed into a set of conventionally accepted signs and became, in the shape of the West Condon Chronicle, what most folks in town thought of as life, or history. . . . That its publisher and editor, Justin Miller, sometimes thought of himself as in the entertainment business and viewed his product, based as it was on the technicality of the recordable fact, as a kind of benevolent hoax, probably only helped to make the paper greater.

On the prognosticated Day of Redemption, the Brunists gather atop a knoll nicknamed Cunt Hill, which overlooks the mine. The event has been highly publicized in advance by Miller, and a crowd forms to watch. A group of drunks set up concession stands and hawk tickets to the event, transforming a figurative media circus into a literal one. It begins to rain, and the cult’s inevitable clash with the Catholic, Presbyterian, and Baptist townsfolk arrives, but the apocalypse does not. “The Powers of Darkness had stormed the holy Mount,” rhapsodizes Miller, “throwing the Sons of Light into dungeons or dispersion, and so there were none there to whom God might, in proper glory, come.”

The Brunists splinter. Signs shift and waver. Light — a holy symbol for the cult — takes on different meanings for different leaders. Clara Collins, the preacher’s widow, begins baptizing her followers in the light of a miner’s headlamp. The hellfire-spitting preacher Abner Baxter prefers baptisms by firelight. For the scientological Elaine Norton, who moves with her husband out to California, holy light is the glow of a television. The Brunists adapt and spread, territory is divided, bishops named. Thus, Coover implies, forms the great feedback loop of the world: tragedy transmuted into myth, myth into belief, belief into religion, religion into division, division into violence, and violence into further tragedy.

Despite the novel’s noisy polyvocality, its message comes through clearly. Near the end of the book, though, one can feel the tenor bending weirdly, as if Coover is smoothing the reader’s transition into the more experimental works to follow: The Origin concludes with a long, rambly joke about Judgment Day, in which heaven becomes so bureaucratically bogged down in processing the billions of new arrivals that God quits.

Coover’s second novel, 1968’s The Universal Baseball Association, Inc., J. Henry Waugh, Prop., completed his transition to a new literary form. It is a metafictional novel, but not in the sense of those “drearily predictable pieces about writers who are writing about what they are writing,” as William H. Gass once wrote. The book’s protagonist becomes so absorbed in his tabletop baseball dice game that the imaginary players’ lives gradually take over the narrative. By the end of the novel, Waugh has disappeared altogether, and the players ponder the existence of God (or “the record keeper”), practice rituals, and divide into religious factions.

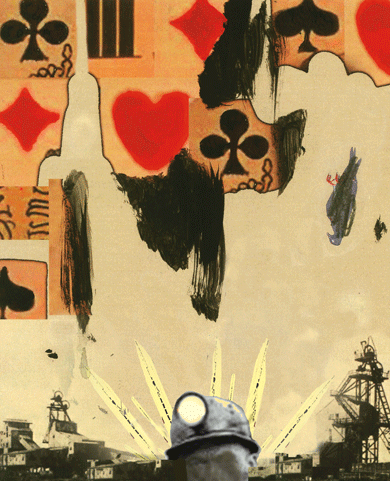

Coover’s next book, the 1969 short-story collection Pricksongs and Descants, also pranked the reader’s unconscious assumptions about narrative structure. The book’s three most famous stories — “The Babysitter,” “The Magic Poker,” and “The Elevator” — are direct attacks on story logic; rather than following a linear plot, the stories unfold in a series of permutations in which everything that can happen happens. In his review of the collection for the New York Times, Gass compared these stories to a deck of cards, in that they could be shuffled and read in any order. It is no accident that Coover would later become the nation’s most visible proponent of hypertextual fiction, nor that a later story collection would include a story printed on a deck of actual playing cards.

The core of Pricksongs — and the bulk of Coover’s career — is composed of stories that reanimate ancient folktales and fairy tales, even television. He often picks up the story line of a beloved character years after the end of the original narrative. So we see Jack as an aging lumberman, feeling more like the surly giant than a sprightly adventurer; Beauty, grown old, resenting the “doggy stink” of the Beast; and Pan leading a flock of ragged sheep through city parks in a technodystopia. When successful, the new myth smudges the original; I, for one, cannot read Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland without thinking of Coover’s remix, in which Alice is still underground, bloated, menopausal, “her whole body like a huge squeezed sponge.”

Coover’s cartoons are not mere parody. The purpose of parody is to make a familiar form look ridiculous. Coover’s aim is to make a familiar form look alien. Or demonic, in the case of his third novel, The Public Burning (1977). The book begins like a conventional history of the Red Scare — it was exhaustively researched — but soon veers into hyperbole. At the novel’s end, the masses gather in Times Square to watch the “burning” (electrocution) of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. The narration vacillates between the voice of an omniscient narrator, the clownish musings of Vice President Richard Nixon, and the folksy prattle of Uncle Sam (a.k.a. Sam Slick), whose monologues are cut-and-pasted from those of past presidents: “Nothin’ is sartin but death, taxes, God’s glowin’ Covenant, enlightened self-interest, certain unalienated rights, and woods, woods, woods, as far as the world extends!” (That last phrase was plucked from a biography of Abraham Lincoln.) The Public Burning briefly made the Times bestseller list and very nearly got Coover sued by Nixon, whose character, in the book’s epilogue, is graphically raped by Uncle Sam.

In this fashion, Coover worked his way through the American storybook. But the urgency of his writing has waned the further he strays from the myths of lived life: politics, religion, and love. His fairy tales — like Briar Rose, the story of a sleeping beauty who never awakes — while gorgeously rendered, can overtax and underwhelm. “Emptiness, the hollow interior, haunts the writer of metafiction when he assaults ossified forms and exhausted language,” warned the critic Neil Schmitz. David Foster Wallace, who considered Coover and Nabokov “real geniuses,” argued that metafiction had once served a purpose but had quickly begun to self-cannibalize: “Metafiction’s real end has always been Armageddon,” he told an interviewer in 1993. “Art’s reflection on itself is terminal . . . It spirals in on itself. By the mid-Seventies, I think, everything useful about the mode had been exhausted . . . By the Eighties it had become a god-awful trap.”

Back in 1964, even before he finished revising the 950-page draft of The Origin down to its final 650 pages, Coover began making notes for a sequel. In fact, he wrote to his friend James Ballowe that he was considering writing a trilogy, the second and third parts then tentatively entitled “The Elder’s Tract on Sacrifice” and “The Brunists’ Holy March.” “All of which proves,” he wrote, “that I’m either a glutton for punishment or, running a little scared, I am laying up a reserve larder in case of coming bad times.” He dragged that larder around for forty years.

For a time, Coover hoped that millennial evangelicalism of the kind he had lampooned in The Origin was fading, obviating the need for a sequel. Then he witnessed the rise and reign of George W. Bush. “This kind of mad apocalyptic view of the world . . . hasn’t gone away,” he told an interviewer in 2008. “If anything, it’s worsened.” In 2006, he began revisiting his old notes.

We have few examples of great experimental writers returning to a conventional mode — Thomas Pynchon’s Inherent Vice, Susan Sontag’s The Volcano Lover, Gertrude Stein’s The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. As in those cases, one thing that is immediately apparent in The Brunist Day of Wrath is its seemingly effortless polish. (By contrast, The Origin feels wildly uneven — one reviewer called the prose “craggy.”) Wrath begins, as The Origin did, with a prologue describing an out-of-town preacher traveling to West Condon. This time it’s one Joshua Jehoshaphat Jenkins, “whushing along through the rain-drenched countryside, the bus nosing out of lush farmlands and dark wet forests onto the gently undulant and somewhat barren coal basin that is to be, if his interview goes well, his new home.” He steps off the bus to find a town “in a state of terminal decay and depression”: prices up, wages down, the mine closed, the downtown scooped out, the bank failing, the countryside scarred by strip mines. Jenkins regards the whole community as “crazed with religion . . . but in some ghastly medieval or else futuristic way.” The town’s Presbyterian preacher, Wesley Edwards, has ingested a loaf of white bread that he believes has transubstantiated into Christ in his belly, and wanders the streets raving.

It’s the same bad spiral, one coil down. On the outskirts of town, the Brunists — now the nation’s fastest-growing new Pentecostal church — have purchased a summer camp and are attracting followers from all over. Again signs are misinterpreted, again a date of rapture is set (7/7), and again they congregate on the Mount of Redemption, as do their enemies.

What arrives this time, though, is the horsemen of the apocalypse, in the form of a biker gang called the Wrath of God. The gang’s ringleader is only a teenager. His head is full of comic-book notions; his rousing orations are described as “short, snappy, in words that would fit inside a speech balloon.” His Benday-dotted worldview colors the prose, particularly at the novel’s climax, when the biker gang lays waste the town. Realists will likely balk at this turn, but Coover’s fans will read it as an extension of his core philosophy: The stories we live by shape the reality we live in. If we keep telling ourselves that apocalypse is right around the bend, one day it will be.

At its weakest points, Wrath can feel like an overgrown movie sequel. (The book is larger than its predecessor in every way; it is 1,005 pages long and features a cast of more than 150 characters.) At its best, it makes The Origin feel like a mere prelude. What ultimately redeems (and transforms) the book is the character of Sally Elliot, who is both insightful and exhaustingly pretentious. An aspiring writer home for the summer from college, she flaunts her newfound rebellious streak — sunbathing topless at the public pool and hand-printing T-shirts with Nietzschean axioms like faith is believing what you know ain’t so. From time to time, Elliot argues with a Lutheran minister named Konrad Dreyer. He takes issue with one of her T-shirts, which reads religion is myth-information.

“But a myth is not a lie, Sally,” Dreyer says. “It’s a special kind of language used to symbolize certain realities beyond space and time. It is information.” (One hallmark of Coover’s maturity is his willingness to put wise words in the mouths of characters with whom he disagrees.)

Throughout the novel, Elliot scribbles in a journal, struggling to craft a new style of fiction. One moment, she is toying with folkloric language; the next, she ponders a style inflected by dream logic — “sensations of flow, flight, fall, heavy-limbed slowness, mazy disrupted travels” — that sounds suspiciously like Coover’s own. Her musings hint that despite this book’s conventional sheen Coover hasn’t, in fact, turned away from metafiction. He has returned to realism only to debunk it:

Like religious people, conventional writers . . . look upon the human story through a particular narrow lens, not crafted by them and belonging to generations of writers long dead. So conventional writers are no more realists than these fundamentalist Rapture nuts are. The true realists are the lens-breakers, always have been.

Perhaps because of her interest in unorthodox modes of perception, Elliot takes a special interest in the Brunists, who in turn figure her an emissary of Satan and try, ultimately, to kill her. She escapes, returns to college, and enrolls in a writing workshop, where she submits one of her experimental short stories. Her professor dismisses it as a “whimsical misuse of a vibrant imagination” and urges her to write something closer to her heart. She begins writing about the disaster in West Condon. To her surprise, the story is accepted by a “prestigious national publication,” and she receives a book offer from a “big New York publisher.” As Elliot begins expanding the short story into a novel, Coover’s final trick dawns on the reader. She is writing her formative horror, her Origin. The sequel has circled back and, gleefully, eaten its own tail.

At the novel’s end, Elliot meets, then marries, a wealthy congressman with a hidden penchant for S&M. She lovingly compares him to “something out of a fairytale.” He asks her to think of him, instead, as a character from one of the Victorian novels she dislikes.

“A kind of ambassador from them, as you might say,” he quips.

“If it’s your mission, Mr. Ambassador, to lure me into those tired woods, you will not succeed,” Elliot replies. “It’s the wildness I want.”