Discussed in this essay:

The Americanization of Narcissism, by Elizabeth Lunbeck. Harvard University Press. 384 pages. $35.

The Narcissist Next Door: Understanding the Monster in Your Family, in Your Office, in Your Bed — in Your World, by Jeffrey Kluger. Riverhead. 288 pages. $27.95.

Imagine yourself a talented, ambitious 1950s Midwestern high school boy who wants nothing more than to become a novelist. You’ve already had a few heady successes as a writer, including first prize in a statewide essay contest, which gave you the confidence to submit your fiction to elite magazines such as The New Yorker and Harper’s, which rejected them (though one rejection, from The Saturday Evening Post, commended your “free-ranging inventiveness”). You’ve gotten yourself accepted to Harvard. But when you arrive, you discover that of all the lousy fates that might befall an ambitious young writer, yours is to be assigned, as your freshman roommate, another ambitious young writer — one who will soon take his place among the most acclaimed novelists and literary stylists of the twentieth century and is already showing signs of genius. It’s a situation that might dissuade even the most confident of kids — some would call it a narcissistic injury.

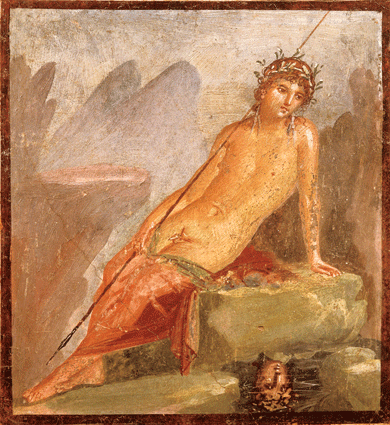

Narcissus at the Pool, fresco, House of Marcus Lucretius, Pompeii, Italy © Gianni Dagli Orti/The Art Archive at Art Resource, New York City

Christopher Lasch, author of the 1979 best-selling rant The Culture of Narcissism, has always struck me as a poignant figure. His capacities for creative defensiveness were already in fine form when he wrote to his parents that his roommate, John Updike, was “a very intelligent kid, and more industrious than I,” but that “his stuff lacks perception and doesn’t go very deep. He is primarily a humorist. As he himself admits he is probably a hack. At least he has more of a hack in him than a profound artist.” For his part, Updike regarded Lasch as sensitive and intelligent but also sulky, with the latter often overshadowing the former.

Still, Lasch and Updike got on well and roomed together until their junior year. Lasch, carefully monitoring everything his roommate wrote, was soon forced to admit that Updike was the more talented. This helped steer his attentions toward history, he later acknowledged, though his ambitions as a fiction writer resulted in an ornate writing style, distressing his professors, who thought he was sabotaging his professional prospects as a historian.

Unwilling to abandon fiction altogether, Lasch kept plugging away at a novel, a bildungsroman “about the author as a sensitive young man, that sort of thing,” as he reminisced in an interview a few months before his death from cancer, in 1994, at age sixty-one. It was never published, though there was a nibble of interest from an editor soon after he graduated. Note that he was still savoring that nibble forty years later, and kept writing novels throughout his life, though he never got one published.

I’ve sometimes wondered about the lasting effects on Lasch of that freshman rooming assignment. Which writer’s signature character, Updike’s Rabbit or Lasch’s narcissist, has had a more robust cultural afterlife? Or, as Elizabeth Lunbeck renders the question in her new book The Americanization of Narcissism: What made Lasch so persuasive that his ideas continue to shape our views of narcissism today, even for those who’ve never heard of him? Her answer is that Lasch skillfully appropriated the language and theory of psychoanalysis. Mine is that The Culture of Narcissism was the Great American Novel Lasch could never write disguised as social theory and that his narcissist is a creature every bit as invented as Rabbit Angstrom — who shares many of the same traits, by the way.

Narcissism was a dubiously mythological concept from the start, and remains a conceptual mishmash to this day. The disagreements over what defines it have been nasty and legion. Lunbeck emphasizes the “protean nature” of narcissism, but this understates the situation. No one — clinicians, theorists, the DSM (the American psychiatric diagnostic handbook, which has redefined “Narcissistic Personality Disorder” in each of four successive editions since the diagnosis was introduced, in 1980) — agrees on the etiology, symptoms, or treatment, and some claim it’s not treatable at all. Do narcissists suffer from excess self-regard or insufficient self-love? Does the condition derive from parents’ insisting their children are “special” or not reinforcing their self-esteem?

No one knows, and yet countless conversations take place these days in which someone deploys the word as a social diagnostic. In the past twelve or so hours I’ve read a book review that opens, “We Americans are a narcissistic bunch,” and an article in the New York Times about “hipster narcissism.” Entire categories of persons are routinely impugned — baby boomers, reality-TV stars, adulterous politicians. Everyone’s ex is, of course, a narcissist: a recently divorced friend reported to me that while he and his wife were on the road to Splitsville she took to leaving books with titles like Freeing Yourself from the Narcissist in Your Life conspicuously placed on her bedside table. It turned out her shrink had pronounced him one, sight unseen. Other mental-health diagnoses — “neurotic,” “compulsive,” “bipolar” — don’t come weighted with nearly as much moralism. Or as much self-exoneration: the one defining trait of the narcissist is that it’s always someone else.

When the sex researcher Havelock Ellis coined the term, in 1898 — his actual formulation was “narcissus-like,” borrowing from Ovid’s myth about the beautiful young lad who falls in love with his reflection in a pool — he was referring to a female patient who masturbated too much. How much is too much, one would like to inquire of Ellis, someone not exactly minus sexual hang-ups himself — impotent until the age of sixty, among other difficulties, about which he was surprisingly voluble in his 676-page autobiography, My Life, a proud forerunner of today’s compulsive self-disclosers.

When Freud took up the concept in his highly speculative 1914 essay “On Narcissism,” he left out Ellis and only briefly mentioned his owlish disciple Otto Rank, who in 1911 had published the first psychoanalytic paper on the subject, “A Contribution to the Study of Narcissism,” though he gets little credit for it in the literature today. Rank’s narcissist was another overly self-reliant woman, one for whom combing her own hair in a mirror was apparently a sexual turn-on, leaving Rank to fret that her self-admiration was so powerful that no one else’s love would ever be sufficient.

Freud expanded the concept by positing two kinds of narcissism: “primary narcissism,” the happy state in which the baby thinks it’s the “center and core of creation,” and “secondary narcissism,” the problematic kind, where instead of developing the capacity to direct your libido outward, you reinvest it in yourself, where it coagulates and festers. The primary-secondary division would eventually translate into the more normative division between “healthy” and “unhealthy” types of narcissism. Healthy narcissism creates ego strength; unhealthy narcissism makes you an asshole.

The 1970s brought growing doctrinal debates among psychoanalysts, which broke down mostly along the healthy-unhealthy fault line. Social theorists, too, started taking up the narcissism cudgel, among them Peter Marin, who published an influential 1975 article in these pages, “The New Narcissism,” in which he lamented the inward turn of the recently developed self-help therapies — encounter groups, primal screaming — and accused those who retreat into self-absorption of “a kind of soft fascism.”

Tough words, yet it wasn’t Marin who brought narcissism to the broad awareness it enjoys today. Lasch’s innovation was to merge two often incompatible strands of twentieth-century thought — the individualizing bent of psychoanalytic therapies and the collective diagnoses of social theory — and to repurpose the fuzzy clinical label as an indictment of affluence, individualism, consumerism, bureaucratization, and other modern ills. Then he dumped the whole contradictory mess on an individualistic, consumption-mad culture, which, surprisingly enough, heaped him with acclaim.

Lasch’s narcissist is one of the great characters of twentieth-century literature. Depression-prone and anxious, plagued by relationship problems and insomnia, he vacillates between, in the words of Lasch, “calculating seductiveness and nervous, self-deprecating humor.” Chaotic, impulse-ridden, and sexually promiscuous, Lasch’s narcissist comes off as so annoyingly self-involved because he has such a thin sense of self. He’s terrified of old age and death; excessively fascinated by celebrities, wealth, and beauty; and full of boundless repressed rage. Though outwardly bland and sociable, inwardly he’s seething. (Lasch was writing before antidepressants became a $10 billion industry in this country, back when people were forced to actually experience their depression.) The narcissist cultivates a protective shallowness; he overestimates his intellect yet lets experts define his needs for him, then wonders why he isn’t satisfied. He lives as though surrounded by mirrors, but he doesn’t like what he sees. He wants what he can’t have — namely, peace of mind. In short, Lasch gives us . . . ourselves.

Even now it’s hard to read the book without feeling defensive and vaguely shame-ridden as you recognize yourself and your least-loved traits page after page. Despite the gloomy social picture and hectoring tone, the book made Lasch an instant celebrity: featured in Time, invited by Jimmy Carter to sup at the White House and confer about why Americans had lost faith in government. (He was seated next to Rosalynn Carter and found the conversation “heavy going.”) None of which seems to have improved his mood: in television appearances from the period (a few are available online), he looks fidgety and ill at ease, someone not entirely comfortable in his own skin.

The surprising thing about The Culture of Narcissism wasn’t just that a culture of alleged narcissists would voluntarily sign up for this protracted scolding but also that Lasch assumed he could inveigh against modern character as though he alone were immune to the forces he was fulminating against. He flings himself around the page with overwrought stylistics, all the while indicting writerly flamboyance — Norman Mailer, author of the presciently titled Advertisements for Myself, was naturally first on his shit list. (Freud’s phrase “the narcissism of small differences” comes to mind.) Yet Lasch also recognized, at some level, that it was practitioners of the Mailerian “garrulous monologue” who, disrespecting the boundaries between cultural criticism and autobiography, were most adeptly registering the transformations in modern selfhood that Lasch was also attempting to chronicle. That recognition is clear in the anguished ambitions of his prose, whether he was conscious of it or not.

That “or not” accounts for the fundamental tension in The Culture of Narcissism. It can be hard to track, at any moment, whether Lasch is describing a social type or just ranting about self-indulgence. Often labeled a left conservative, Lasch certainly has the conservative’s inclination to blame individuals for collective fates. He was a critic of capitalism who hated the Sixties, social movements, multiculturalism, and all loose talk of liberation. Even antiwar protesters weren’t exempt from his ire (not that he was pro-war) — their leaders were self-promoting, he accused. The women’s movement hit him especially hard. Feminists were shrill; he took their demands as a personal affront. The Culture of Narcissism is basically a cornucopia of affronts, with Lasch raging, wounded, and arbitrary, bleeding all over the page and calling it social critique.

So where does Lasch’s brilliant and deranged book leave us? Mired in a lot of reflexive finger-pointing, to begin with, since, as Lunbeck makes clear, it’s Lasch’s conception of narcissism that’s most decisively shaped how we think about it at the moment.

Lunbeck, an intellectual historian, opens her prodigiously researched reconstruction of the story of narcissism with Lasch — she charges him with creatively misreading the clinical literature. The psychoanalytic debates of the 1970s were largely conducted between Heinz Kohut, known as the inventor of “self psychology,” who took a rather forgiving view of narcissism, and his opposite number, Otto Kernberg — or as I like to think of them, the good cop/bad cop routine of narcissism theory. While Kohut celebrated the potential of “healthy narcissism” and was a proponent of therapeutic empathy (in contrast to traditionally stony orthodox Freudians), Kernberg emphasized narcissism’s destructive side; he accused Kohut of coddling his patients, who needed to be confronted with their Oedipal problems. Kohut saw a world in which our ambitions and creativity are fueled by stores of self-love; Kernberg saw “a hungry, enraged, empty self, full of impotent anger at being frustrated, and fearful of a world which seems as hateful and revengeful as the patient himself.”

Lunbeck is exceptionally good at disentangling these often arcane psychoanalytic arguments and their reverberations in postwar social theory; she’s also very good on the intersections of saving, spending, and desiring in both psychoanalysis and consumer culture. What Lasch got wrong, she says, was imagining that Kohut, who invariably sided with gratification over renunciation, was a compatriot; he was anything but. The consequence, she thinks, has been the popularization of the malignant narcissist and the overall neglect of the positive aspects of narcissism in our current conceptions.

Lunbeck takes what might be called a maximalist approach to her subject: if anyone’s mentioned narcissism in the past hundred years, she’s there with a clipboard. The downside of this admirable thoroughness is that it bogs us down in detail, the way a hoarder’s living room becomes jammed with clutter that eventually entombs the occupants. What’s hard to locate amid all this is any skepticism about the utility of the concept, particularly given its moralizing deployments in the American context. Lunbeck is also not entirely immune from the satisfying amour-propre invariably found in those wielding accusations of narcissism. In her case, the target of the accusation is Freud himself, along with his cohort.

Many early analysts speculated that homosexuality and narcissism bore a family resemblance: one is, after all, taking up a love object like oneself. Aha! says Lunbeck. Freud’s own friendships were suffused with homoeroticism: there was his odd association with Wilhelm Fliess, a Berlin doctor with strange theories about nostrils; his “fantasies of merger” with Carl Jung; and his tortured relationship with Sándor Ferenczi, a younger Hungarian analyst whom Freud befriended, professed his love for, and then fell out with. (Ferenczi was an early proponent of empathy in analysis, the mantle Heinz Kohut would later take up.) This is all entertaining in a gossipy way, but Lunbeck succumbs too much to the desire — not uncommon among psychoanalytic critics — to put Freud on the couch and beat him at his own game, revealing his unconscious desires:

Thus, even as Freud was collapsing homosexual desire and paranoia, he was engaged in struggle with his own homosexual attachment to Fliess and attempting to ward off the psychosis that his developing theory told him attended it. Freud rejected Ferenczi at the moment when he felt he had mastered his need for Fliess. Was Ferenczi’s need for Freud intolerably reminiscent of his own need for Fliess?

Freud had a name for this kind of thing: wild psychoanalysis, which means forcing interpretations on a patient. If Freud’s blind spots, which were certainly many, had invalidated psychoanalysis, I assume his critics and second-guessers wouldn’t be quite as eager to demonstrate their own skill at it.

Then we get to Freud’s relations with his wife, Martha. It’s not exactly news that Freudians weren’t always at their best with women, in theory or on the couch. But Lunbeck makes it personal, amping up the criticisms of Freud to include his domestic arrangements: he relied on his wife for household sustenance — she even laid out his clothes for him! — and on his sister-in-law and children for clerical help and travel arrangements. Perhaps so, but was he supposed to be an enlightened modern househusband making beds and swabbing floors between patients? Lunbeck makes a more interesting point when she charges Freud with pathologizing dependency and assigning it to the realm of the feminine, but follows up with more personal jabs: “It may have been that his skittishness about his own dependencies” shaped his views on narcissism. He fancied himself without needs or wants while relying on his family to take care of him; it’s no coincidence that primary narcissism (“His Majesty the Baby”) was held up by early Freudians as the psychological ideal.

Lunbeck ignores the degree to which Freud’s conception of narcissism was genuinely speculative — as he says throughout the essay. As far as what Freudians got wrong about women, the more intellectually challenging question is what they got right. Lunbeck assumes that concepts like penis envy, which she spends a fair amount of time rehearsing, are self-evidently useless. To my mind penis envy is an interesting heuristic, precisely because it prompts so much defensiveness in women, even now. When Lunbeck detours through fashion in a section on vanity, she bristles when Freud asks his colleagues, in 1909, why women keep bowing to fashion’s dictates and wearing unflattering clothes. Bristle we might, but considering the recent trend of skinny jeans cut so low that everything above billows into the cruelly designated “muffin top,” it’s still a shrewd question.

I suppose the women adopting such looks are hoping for some kind of love from the world. One term for this, we learn from Lunbeck, is “narcissistic supply,” code for admiration and attention. It makes the recipients sound like creatures from the pages of Bram Stoker:

The narcissist hungers for tribute and, more elementally, for narcissistic supplies that can literally take the form of “food.” Other people are envisioned as having food inside that the narcissist can devour.

One analyst suggests that other humans exist in the narcissists’ minds the way a hamburger exists — simply to make them feel good.

These narcissists sound suspiciously similar to the vampires lately overrunning the cultural landscape, sucking the vitality from the living. Turning from pop culture to pop psychology and back, you can’t fail to notice how heavily writers in both genres lean on horror-show imagery and panic mongering. Narcissism has “spread through the generations like a particularly pernicious virus,” intone the co-authors of The Narcissism Epidemic: Living in the Age of Entitlement (2009). “Americans’ immunity to narcissism has weakened,” they continue. “Corrosive narcissism . . . threatens to infect us all.” Borrowing the jargon of epidemiology, they label the worst culprits — celebrities and reality-TV stars, obviously — as “superspreaders” who disperse pathogens far and wide, the Typhoid Marys of our day. Virtually everything toxic in the culture is due to narcissism — the housing bubble and government debt are clear symptoms of narcissism run amok, O. J. Simpson was an example of a narcissist crossed. The authors (both Ph.D.-certified psychologists) even borrow a page from the HIV moral panic mongers by regarding the transmission of narcissism as both viral and a moral choice. They’re derisive about the idea that narcissists are compensating for low self-esteem: no, no, narcissists “like themselves just fine and even more than the average person,” pronounce the 100 percent disease-free authors.

The latest addition to this canon is Jeffrey Kluger’s The Narcissist Next Door: Understanding the Monster in Your Family, in Your Office, in Your Bed — in Your World. Kluger, a science writer for Time, takes a capacious view of the subject. Here we have not just the usual celebrity suspects (Miley Cyrus, Charlie Sheen, Lady Gaga) on parade but every presidential candidate throughout history (running for office “requires a level of vanity that seems to border on madness”). Maybe MLK and Gandhi, too — after all, says Kluger, they got a charge out of rousing crowds. Also under suspicion: Sarah Palin, Caligula, Stalin, Hitler, Saddam Hussein, Fidel Castro, and the Columbine killers. “It surely begs the point to say that the boys were narcissists,” Kluger says of the high schoolers, “though they manifestly were.” Josef Mengele is an example of a “malignant” narcissist, though, Kluger adds helpfully, “not all psychologists agree that malignant narcissism actually exists.”

In what possible way is our understanding advanced by using the same word to describe Mengele, the Columbine killers, and someone who talks about herself too much? Not to mention journalistic fabulators, point guards who don’t show up for drills, spouse batterers, and pretty much anyone else who defies any professional or interpersonal norm? Lasch should take a posthumous bow for providing us with such an all-embracing term — though, proving Lunbeck’s point about his stealth influence, Kluger never mentions him.

Frankly, the clinical literature on narcissism isn’t much more coherent. A representative sample, organized chronologically, can be found in the volume Essential Papers on Narcissism (1986), and should you appoint yourself the task of reading through it, you’ll find that until the 1970s, when Kohut and Kernberg took up the question of treatment protocols, analysts tended to define narcissists as the patients whom treatment failed to improve. What a self-exonerating diagnostic criterion! One notices, over the course of the twentieth century, a subtle movement away from definitional concepts and toward the destructive effects treating narcissists has on the therapists. Narcissistic patients devalue us, complain the shrinks; they’re contemptuous, they don’t listen, they treat their therapists as employees. In the words of one beleaguered analyst whom Lunbeck cites, they’re demanding, controlling, tyrannizing, insatiable, and destructive. You start to wonder whether the shrinks are the ones who need validation and affirmation, and the patients who don’t supply it — well, those are the narcissists.

Hence the diagnostic proliferation of the term, perhaps. A 2009 metastudy of the clinical literature found that there were more than fifty subvarieties of narcissism: “amorous,” “compensatory,” “phallic,” “fragile,” “craving,” “paranoid,” “manipulative,” and on and on. It’s basically a Tower of Babel, the authors conclude, inconsistently reported and patchily conceptualized.

Listening to the babble, you have to wonder what this ecstasy of diagnosis is really about. Clearly there’s some problem in the sphere of personality; a species of person roams the social landscape creating discomfort. Their balloonish egos impinge on the space apportioned for yours. It feels like they’re guzzling too many resources, exceeding the self’s socially allotted dimensions. No doubt they feel the same way about you.

Freud’s initial nervousness about narcissism was that too much self-love diminishes the quantity available for someone else. How much love for me versus how much for you? The same anxieties continue to haunt our interpersonal equations. Maybe the babble comes down to one basic question: Why can’t you give me what I need? It’s a form of higher interpersonal arithmetic, though, at the same time, infantile. And, as everyone knows, futile: once you enter the sphere of calculations you’ve already lost what bounties could have been yours. Love is a gift economy.

Still, this is the condition of modern selfhood: insatiability. Fortunately there’s the Internet. Technology has stepped in to bolster those needed narcissistic supplies, providing love and attention on demand, plus you can talk about yourself all you want. Here’s an irony: at the turn of the twentieth century Freud invented the talking cure to heal what ails the modern psyche. A century later, even as psychoanalysis has fallen into disrepute, people can’t stop talking about themselves — the cure has become the symptom of the new ailment.