Discussed in this essay:

Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes, by Svante Pääbo. Basic Books. 275 pages. $27.99.

The Neanderthals Rediscovered: How Modern Science Is Rewriting Their Story, by Dimitra Papagianni and Michael A. Morse. Thames & Hudson. 208 pages. $29.95.

Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth, by Chris Stringer. Times Books. 320 pages. $28.00.

Human identity turns out to be more complicated than you think, though no doubt you think it’s pretty damn complicated. We carry our evolutionary history in our genomes, and our history is a very mixed record. In recent years, a cluster of scientific studies of ancient DNA — specifically, DNA retrieved from Neanderthal bones — has cast some startling new light on several old questions, such as: What happened to the Neanderthals, who seem to have disappeared from their last European enclaves around 30,000 years ago? What happened to us, about the same time, such that we began painting wonderful art on the walls of caves, developed new methods of tool-making and means of communication, and emerged as the last, most successful form of hominin on Earth? Did we kill the Neanderthals off, did we drive them extinct by inexorable competition, or did we merely arrive by coincidence as they failed? Or, still another possibility, did we subsume them (despite the species “barrier”) by interbreeding?

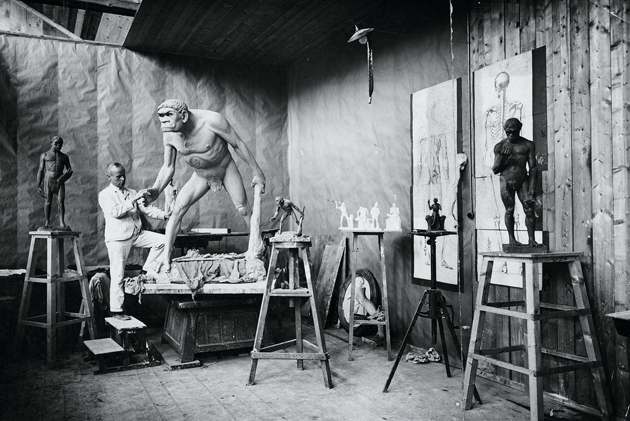

Photograph of a man carving a Neanderthal replica © ullstein bild/The Granger Collection, New York City

Three recent books help to place these questions within a broader context of paleoanthropology as practiced over the past forty years. The Neanderthals Rediscovered, by Dimitra Papagianni and Michael A. Morse, is focused squarely on the Neanderthals in their own right — how they lived, how they evolved, how they inhabited Europe for at least two hundred millennia. “We wanted to write a book on the Neanderthals that does not dwell too much on the false turns in the long history of research and does not get easily distracted by the entry of Homo sapiens on to the scene.” It’s an admirable resolve. Papagianni, an archaeologist who specializes in stone tools, and Morse, a science historian, consider the evidence of obsidian blades, flint scrapers, hand axes, hammerstones, spear points, and expertly knapped flakes — artifacts that reflect who was living where, and when, and practicing hunter-gatherer skills with what levels of sophistication and forethought. Much can be read from a fist-size hunk of chipped rock.

Chris Stringer’s Lone Survivors, on the other hand, takes the emergence and triumph of modern humans as its central topic. Stringer, a paleoanthropologist based at the Natural History Museum in London, is an authority on human evolution in general, Neanderthals more particularly, and a forceful proponent of what’s called the Out of Africa model of human prehistory. According to that model, one group of humans emerged as modern Homo sapiens about 50,000 years ago, in Africa, following revolutionary changes in tool-making and other complex behaviors. From Africa, Stringer tells us, these new people dispersed to Europe, where “they quickly took on and replaced the Neanderthals through their superior technology and adaptations.” Hence the alternative label for that scenario: the Replacement model.

In his scientific memoir, Neanderthal Man, Svante Pääbo, a Swedish-born evolutionary geneticist, describes his early dreams of being an Egyptologist, inspired by a trip to Egpyt with his mother when he was thirteen. He became fascinated with mummies, memorized hieroglyphs, and worked summers at a museum cataloging pottery shards. But he soon realized that the discipline “was moving too slowly for my tastes.” Instead he studied medicine, then shifted to a research career in molecular biology, “with its apparently boundless promise of advances in the welfare of humankind.” Notwithstanding the exigencies of human welfare in the present, he found himself still intrigued by the shape of the human past. “Could it be possible to study ancient DNA sequences and thereby clarify how ancient Egyptians were related to one another and to people today?” Pääbo is now director of the genetics department at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig. His curiosity about pharaonic Egypt led him to the still-deeper past, of 30,000 to 50,000 years ago, when Neanderthal history came to its sudden halt.

These three works are especially interesting in combination because, besides giving us a trio of perspectives on the Neanderthals’ rise and fall, they exemplify a bigger theme in modern science: the decades-long schism between organismic and molecular biology. Organismic biology, the more traditional of the two, looks at whole organisms (such as animals and plants) and populations, to consider their ecology and evolution. Molecular biology looks at the molecules of life, in particular DNA, to consider the minute mechanics of biochemistry and heredity.

Organismic biology is holistic — so its partisans would argue — whereas molecular is reductionist; or, as viewed from the other side, molecular is mechanistic and precise whereas organismic is descriptive and woolly. You may have missed this argument, unless you work in the field or are somehow involved with the allocation of university budgets and buildings. It has been quiet and internecine but bitter, and traceable back to the late 1950s and early ’60s, when Edward O. Wilson (organismic) and James D. Watson (molecular) were young scientists competing for tenure at Harvard — an archetypal contest, as described in Wilson’s memoir Naturalist — and when elders such as George Gaylord Simpson, Ernst Mayr, and Theodosius Dobzhansky (all organismic) published grumpy essays under such titles as “The Crisis in Biology.”

The schism persisted for decades but has narrowed and healed somewhat in recent years, with molecular biologists rediscovering the fascination of evolutionary questions and organismic biologists becoming more appreciative of molecular methods. The two camps still compete for esteem and resources, though not as snarkily as in the past.

The mystery of the Neanderthals represents a good test case because scientists converge on it from both sides (Stringer and Papagianni and Morse from the organismic, Pääbo and his team from the molecular) and because the available evidence is so severely limited: stone tools, bones, precious traces of ancient DNA. It’s impressive to see science, of any sort, making so much of so little.

Until the middle of the nineteenth century, no one knew for certain that any other species of human or humanlike creature had ever shared the planet with us. In those years before Darwin announced his theory of evolution, the prospect was scarcely imaginable — except to certain pseudoscientific pontificators, mainly white males in Europe and America, who viewed the different human races themselves as distinct species. Fossils of dinosaurs and other extinct beasts had begun turning up and causing perplexity (the very idea of species extinction was heterodox), but almost nothing had been found that suggested earlier, alternate forms of humanity. A child’s skull taken from a cave in what is now eastern Belgium in 1829 and an adult skull discovered in a Gibraltar cave in 1848 were recognized retrospectively as Neanderthal but set aside at their times of discovery without special notice. Then, in 1856, workers quarrying limestone from still another cave, on a steep slope above the Düssel River in the Neander Valley near Düsseldorf, Germany, unearthed bones of what they thought might be a cave bear. (Cave bears had been known as a vanished species, their bones left behind in many European caves, for almost a century.)

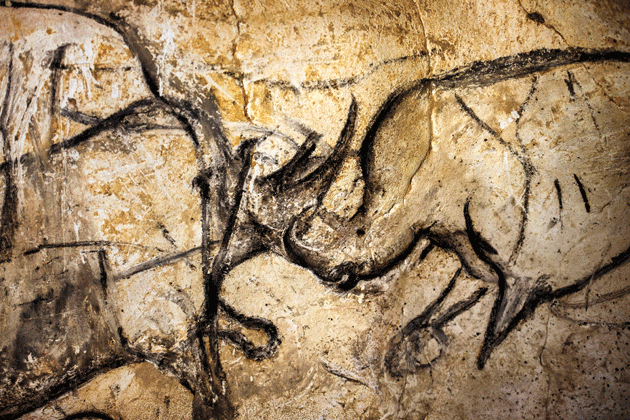

Photographs of paintings on the rock walls of the Chauvet Cave, near Vallon-Pont-d’Arc, France © AFP Photo/Jeff Pachoud

The chief quarryman passed these Neander Valley “bear” bones along to a local schoolteacher with an interest in natural history, Johann Karl Fuhlrott, who saw with a jolt that, far from being ursine, they must have come from some unknown form of humanoid being. There was a skull cap with raised brow ridges, two femurs, five arm bones, and other fragments. Fuhlrott in turn shared them with Hermann Schaaffhausen, a professor of anatomy at the University of Bonn, who delivered a paper to a natural-history society arguing that these were the bones of a new kind of human, dating back to a time before the “barbarous races” of Europe, before the Celts and the early German tribes, before even the Flood. Over in London, after Thomas Huxley got interested by way of Schaaffhausen’s account, Fuhlrott sent him a plaster cast of the cranium. Huxley described the Neanderthal fossils in his 1863 book, Man’s Place in Nature, setting them provocatively within the context of his friend Darwin’s theory, which had finally been published (after two decades of Darwin’s cautious delay) four years before. That same year, at the meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, a geologist named William King gave the Neanderthals the name that has stuck: Homo neanderthalensis. As Papagianni and Morse note, King became “the first person to use fossil evidence to name an extinct species closely related to our own.”

The Papagianni and Morse book is a steady, linear account, the least discursive and personal of these three, marching forward through the past million years of human history in Europe as inferred from the evidence of stone tools. The authors take us in and out of many, many caves: Sima del Elefante in Spain, Petralona in Greece, Gorham’s in Gibraltar, Tabun and Kebara in Israel, Pestera cu Oase in Romania, Vindija in Croatia. The Neanderthals Rediscovered has the fresh charm of treating human evolution as a curious story that leads to the Neanderthals, rather than as a moral tale that rises ever upward and inevitably to us godlike moderns. The book is at its best in the middle chapters, covering roughly 250,000 to 60,000 years ago, that period when the Neanderthals evolved (probably from still another human species, Homo heidelbergensis, which had come out of Africa much earlier) and found ways to survive on a northern landscape despite intermittent ice ages.

Tools were important to that struggle, but you had to be patient. “For the first 1.5 million years after the invention of the handaxe,” Papagianni and Morse write, “there was little improvement in stone technology.” Then the pace quickened. Someone invented what’s now called the Levallois technique of tool-making (it wasn’t Nicolas-Eugène Levallois, a real estate entrepreneur who merely gave his name to a Paris suburb where such tools were first found), an improvement that signaled forethought as well as practicality. The essence of the Levallois technique is that it proceeds from a core, a blank of good rock, from which usable blades can be whacked off in successive flakes by skillful knapping. A toolmaker using this method would have needed to select cores showing extended promise and might have carried one from place to place, knapping off new flakes as needed. Papagianni and Morse call it “an important cognitive leap forward,” signaling the emergence of the Neanderthals.

Photographs of paintings on the rock walls of the Chauvet Cave, near Vallon-Pont-d’Arc, France © AFP Photo/Jeff Pachoud

Following that breakthrough, the Neanderthals had their own “classic” period, from about 60,000 to 45,000 years ago, during which Earth’s climate was relatively mild, and they expanded their range northward in Europe and eastward into Asia. Papagianni and Morse remind us that these were a successful people, to a degree, for a time. Expert hunters, with Levallois tools, they “survived in harsh climates by developing clothing and fire. They buried their dead and cared for the sick. They exploited a range of food resources including from the sea. They used red ocher, possibly for symbolic purposes.” Red ochre may have served as a dye, making hides or bodies bright and pretty. But the Neanderthals fell short of the ability (or desire) to produce jewelry from little beads and shells. That is a vanity unique to us moderns.

Then came their end. Papagianni and Morse suggest it was the modern people of Gravettian culture, perhaps combined with another period of climatic chilling, who pushed the Neanderthals to their sad, undramatic oblivion. The Gravettians made fancier tools of flint and bone. They established long-term settlements, and they stored food. They produced buxom female figurines, a sign of symbolic imagining and healthy sex drives. They caught fish from the rivers and hunted migratory animals across the steppes. All this was beyond the Neanderthals. Most tellingly, modern humans increased their population density as well as their geographic reach. They thrived on the open grasslands that were expanding across northern Europe and Asia as the climate changed. The Neanderthals shrank back to their last refuges, possibly in Spain and elsewhere along the southern edges of Europe, and then they were gone.

Chris Stringer has co-authored several books for general readers (and hundreds of scientific papers) on the evolution of modern humans and our various cousin species, including the Neanderthals. Lone Survivors, published in 2012, centers on the question of why we, Homo sapiens, have been the sole representative of the considerable diversity of hominin forms to persist until now. Stringer trained as an anatomist and works primarily by morphometrics, measuring and comparing the shapes, sizes, and growth patterns of bone. Skulls are especially important, especially telling, for this mode of deduction. He recounts, in Lone Survivors, a 5,000-mile road trip he made as a scruffy young Ph.D. student, back in 1971, to visit collections in ten European countries and take measurements from the skulls of Neanderthals and their modern-looking successors, who were then known as Cro-Magnons (and nowadays are simply called early modern humans). With him he carried “a small suitcase full of metal measuring instruments, such as calipers, tapes, and protractors,” as well as a camera to record the basic shapes of the specimens and their state of preservation. He arrived back at Bristol University after four months of camping in his car and sleeping in hostels, having survived several border hassles and two robberies, carrying “one of the largest data sets of Neanderthal and early modern skull measurements assembled by anyone up to that time.” Stringer transferred his data to punch cards and fed them into the university’s computer, a machine as big as several rooms but with a tiny fraction of the processing power of an iPhone. One point of this exercise was to judge whether Neanderthal and modern human populations seemed continuous, a single evolving lineage. Based on his analysis of the data he collected, he decided that the two species were discrete. Modern humans, he argued, newly immigrated from Africa, had replaced Neanderthals rather than merging with them.

Stringer now refers to his theory as the Recent African Origin model rather than the Out of Africa model (to distinguish modern humans from earlier waves of African migration). A rival concept, proposed in the 1930s by a German scientist and later developed by an American paleoanthropologist named Milford Wolpoff, is known as the Multiregionalist model. It suggests that Homo sapiens emerged from its predecessor species, Homo erectus, not by a relatively sudden revolution in Africa, as Stringer believes, but by a more gradual process that involved gene flow and change throughout the entire range of human distribution, including Homo erectus in Asia and Africa as well as Homo neanderthalensis in Europe. People traveled, albeit slowly; they interbred wherever they went; advantageous mutations spread from one place to another; and the whole, vast, interconnected population of humans advanced incrementally, without diverging into multiple species and without any discrete group replacing any other. One corollary of this model is that, while Neanderthals certainly existed, the species Homo neanderthalensis did not. It’s a taxonomic mistake. There are splitters and lumpers in taxonomic practice, inclined to err in opposite directions; Wolpoff is a lumper, and, to him, Homo neanderthalensis is a false category imagined by the splitters. Stringer disagrees. He sees the reality of Homo neanderthalensis in its bones — the skull with its great brow ridges, the suprainiac fossa (a small depression in the occipital bone), the burly femurs — which he has so carefully gazed upon and measured.

Stringer’s book is rich in ideas, facts, expertise, historical anecdotes, and speculations, but poor in organization, focus, and flow. It’s like a midden of interesting things — bones, discarded tools, camp garbage, and other suggestive remnants — piled deep over the years and available for excavation and interpretation, if you have the patience. Mine wore thin. He zigzags in time and space, forward, backward, sideways, from one idea or one discovery to another. He mentions dozens of fellow scientists, but passingly, without sketching any memorable characters, and he alludes to controversial pieces of work, sometimes without saying who did it or where an interested reader could find the publication. Maybe he knows this material, with all its twists and turns and divagations, so well that he can scarcely stand back from it and sketch a coherent pattern.

Svante Pääbo’s work on old, recoverable DNA began with mummies, looped around through quaggas and Pleistocene ground sloths, and came to sharp focus on that original cluster of Neanderthal bones salvaged by the schoolteacher Johann Fuhlrott in 1856. Those bones, now collectively known as Neanderthal 1, had become the type specimen (the permanent standard for taxonomic comparison) of the new species. Chris Stringer measured some of them, notably the skull cap, during his travels in 1971. Twenty-five years later, in 1996, Pääbo got hold of a small piece of bone from that same individual.

It was just 3.5 grams of material, cut from the right humerus with a sterile saw by an obliging archaeologist at the Rheinisches Landesmuseum in Bonn, where the Fuhlrott fossils were held. One of Pääbo’s graduate students, Matthias Krings, extracted fragments of DNA from the pulverized sample and fed them into a fancy new DNA-sequencing machine. As the results began to emerge, Pääbo received a late-night call from the lab.

“It’s not human,” Krings said. What he meant was: It’s not modern human DNA; it’s not contamination from us or others. It’s the real deal, what we’ve been looking for — Neanderthal DNA.

“I’m coming,” Pääbo mumbled, and threw on some clothes.

Neanderthal Man opens with this episode, and it’s a nice touch by Pääbo, bringing us straight to the moment when his long, painstaking effort to tease ancient DNA out of hominin fossils yielded its first dramatic results. He admits his pride in the paper published soon afterward in the journal Cell, by him and Krings and four colleagues, announcing their achievement and its apparent meaning. What they had done was isolate fragments of mitochondrial DNA (easier to gather than nuclear DNA because it’s more abundant in each cell, but inherited only from mother to offspring), reassemble those fragments into a continuous stretch, and compare that Neanderthal sequence with the equivalent stretch as found in living people. Their analyses showed that the Neanderthal sequence fell outside the range of variation in modern humans. It had contributed nothing to us. That result, Pääbo’s group declared, “supports a scenario in which modern humans arose recently in Africa as a distinct species” and had replaced Neanderthals “with little or no interbreeding.”

Stringer attended the press conference at which Pääbo’s discovery was announced, and, as Stringer writes, “I remember getting so carried away that I hailed it as an achievement comparable with landing someone on Mars!” Or maybe just landing on the moon, as Pääbo’s version has it. Anyway, a signal achievement — and a reminder that human memory (was it Mars or the moon?) isn’t quite so precise as molecular biology.

But the Pääbo team had hedged their claims. Their results, while showing no contribution of mitochondrial DNA from Neanderthal mothers to the modern human lineage, did not rule out the possibility that Neanderthals had contributed “other genes to modern humans.” In his book, almost two decades later, Pääbo tells the full tale of how that hedge proved prescient, and how his subsequent work showed that the provisional finding — no gene passage from Neanderthals to modern humans — was wrong.

In the new century, three Neanderthal bones from another site, Vindija Cave in Croatia, yielded enough nuclear DNA for Pääbo’s team to sequence more than 4 billion nucleotides from the three individuals and assemble a draft sequence of the entire Neanderthal genome. That itself was an amazing accomplishment, but only a data-gathering prelude to what further analysis would reveal. Comparing the Neanderthal genome against those of living people, Pääbo and company found that between 1 and 4 percent of the DNA in modern Europeans and Asians has come down from ancestral interbreeding with Neanderthals. (Africans don’t show this hybridization, probably because Neanderthals never got to Africa.) Pääbo admits that he was astonished when he saw the preliminary results on his computer screen: “It contradicted what I myself had believed to be true. Neanderthals weren’t totally extinct. Their DNA lived on in people today.”

Stringer hasn’t let Pääbo’s genetic discoveries dispirit him. “Given that interbreeding seemingly did happen between modern and archaic humans, both in and out of Africa, does this mean that we should now abandon the different species names and lump all the fossils of the last million years or more as Homo sapiens, as some suggest?” His answer is no. He has an emended model that absorbs the new molecular evidence, like a soft bag taking a hard punch. He calls it Recent African Origin + Hybridization, and it represents a compromise: modern humans did emerge from Africa around 50,000 years ago, but then, after encountering Neanderthals in the Middle East or in Europe, they interbred to a limited degree and picked up some exotic genes. Our ancestors were adaptable, and Chris Stringer is adaptable, too.

The story has continued to unfold since Pääbo’s book went to press. Studies published earlier this year by two independent groups, one of which includes Pääbo as well as the Harvard geneticist David Reich, the other led by Joshua Akey at the University of Washington, find that somewhere between 20 and 40 percent of the total Neanderthal genome lies scattered among the genomes of living people. Some of us carry more of that legacy than others: East Asians, for reasons unknown, seem to have retained greater shares than Europeans.

The question that immediately follows from discoveries of Neanderthal genes in our lineage is: To what effect? And that question isn’t easy to answer, not even with the fastest DNA-sequencing machines and the best software for patching sequences into genomes. Somebody still has to figure out what that Neanderthal DNA does in our bodies, if anything, and how various bits of it may have affected our evolutionary history. Along that line, the Reich–Pääbo and the Akey studies have converged on one interesting, provisional answer: Many of us seem to carry Neanderthal genes that work in the production of keratin, an important component of our skin and our hair. The fact that these genes have remained with us through at least thirty millennia of natural selection suggests that they’ve been doing something at least marginally useful. But nobody, not even Pääbo, can say what. Have they helped protect us against sunburn, or skin cancer, or ringworm, or the winter cold, or reproductive disadvantage due to baldness? Maybe. Maybe not.

Nor has genomics been able to answer that other big question about the Neanderthal brush with modern humans: Why did we blossom so imposingly just as they wilted? Skull shapes don’t explain it. Improvements in tool-making don’t explain it. The raw data here include those magnificent wildlife images on the walls of the caves at Lascaux, Altamira, Las Monedas — and especially at Chauvet, with its surging horses and aurochs, its long-horned rhinos, its exquisitely watchful and lovingly depicted lions.

Chauvet, undiscovered until 1994, lies in the Ardèche valley of southern France. Its art has been dated to around 30,000 years ago, by which time the last Neanderthals had probably straggled away from most parts of Europe, or died off, leaving only a few hybrid children among the newcomers. Then something happened. Someone began to paint.