Discussed in this essay:

Severed: A History of Heads Lost and Found, by Frances Larson. Liveright. 384 pages. $27.95.

Jivaro is the name of a professional headhunting firm with offices in four American cities. The company’s website boasts of finding individuals with the “expertise, knowledge and drive needed to help take your company to the next level.” Its logo features a stylized red warrior striding along with his spear hoisted for the kill.

The term “headhunting” is now synonymous with executive searches, but few of Jivaro’s clients, I would wager, have read F. W. Up De Graff’s 1923 classic Head Hunters of the Amazon: Seven Years of Exploration and Adventure, the most thorough account of the technique of procuring and preparing human heads as it was practiced by the Jivaro tribes of the upper Amazon. After a victim was decapitated with axes, blades, or sharpened clamshells (sometimes while he or she was alive and struggling) the head was strung up, with a bark rope passed through its neck and out its mouth, then transported for fireside preparation. A medicine man blew chewed tobacco up a warrior’s nose, and then the warrior peeled the flesh from the skull, sewed up the eyelids and mouth, plugged the nose, basted the neck meat, and cooked the head in hot, but never boiling, water. When the cooking was finished, the head was filled with sand. A slick of yellow grease floated atop the cooking water.

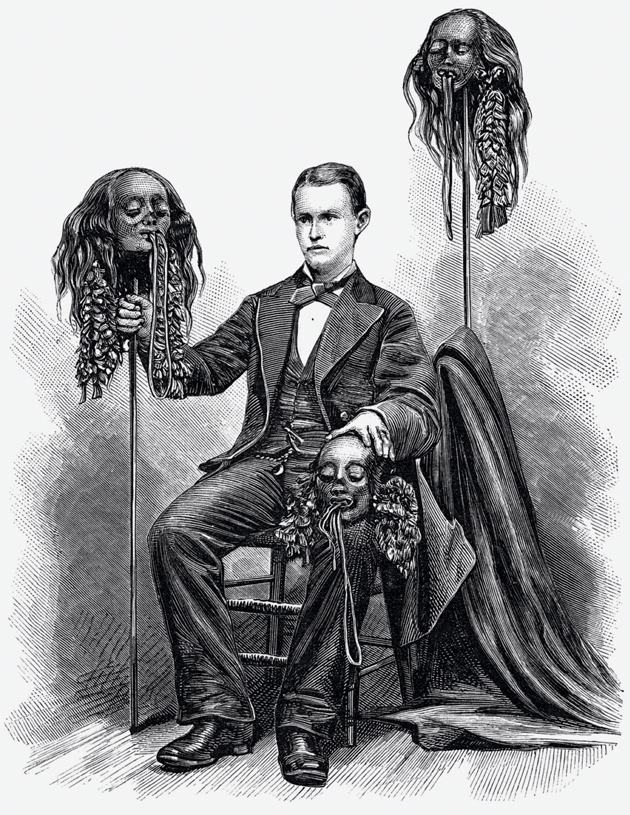

Ernest Morris, an explorer of South America, poses with shrunken heads from the upper Amazon, 1877 © Granger, New York City

Books like De Graff’s rode an American and European vogue for shrunken heads, tsantsas, which were originally used only in sacred tribal rites. Until the beginning of the twentieth century, the usual price of a tsantsa was one gun. The guns that were traded for heads were used to kill more people and produce more heads. Almost right away, Frances Larson writes in her fascinating new book, Severed, “women’s and children’s heads, severed by European knives, ended up on the streets of South American towns and cities to be sold as souvenirs.” By the early twentieth century, a tourist could buy a shrunken human head, now known as a tourist head. The demand for these items fed markets in grave robbing and murder, though many heads were taken from unclaimed bodies in morgues and hospitals. You could purchase a shrunken head and have it delivered to your home.

Headhunting, along with cannibalism, is savagery’s purest form and most recognizable symbol. And yet the collection and display of heads has often been a sign of one’s sophistication, refinement, and superiority over the supposed monsters who supplied them in the first place. It is amazing how easily culture can launder violence into something morally acceptable by making a head a commodity. The transaction forever washes away the taint. When we see a shrunken head in a museum or private collection, what we see is our superiority over societies that would ever do such a thing as hunt heads. Though the trade in tsantsas was driven by Western fascination with, as Larson puts it, “an untouched savage people,” shrunken heads are in fact “the gruesome trophies of a western fascination with the idea of an untouched savage people.”

Like other curious artifacts, from Roman coins to mummy wrappings to Nazi memorabilia, tsantsas can now be purchased online with relative ease. Most are imitation heads made from goat and other animal skins, but even authentic tsantsas were made to be sold to collectors, who, several degrees removed from the original violence, still line up to buy them. Last summer, I spoke to Glenn McGinty, who owns the website realshrunkenheads.com. McGinty sells mainly tourist heads produced in Ecuador between 1880 and 1950, which often come to him from families who discover them in attics and shoe boxes and, he says, want them gone. Many have insect damage, but a good head sells for around fifty thousand dollars. There are no laws against buying shrunken heads, which are legally considered antiques. Even Christie’s has auctioned them from time to time.

Severed is a typological study that links severed heads of all sorts and uses. The book suggests that detached heads have their own history, which transcends the histories of execution, murder, voyeurism, and colonial violence that produced them. Not surprisingly, the through-line connecting these diverse cases is money. Take James Sligo Jameson, heir to the Jameson whiskey fortune, who, in 1888, on a trip to the Congo to witness cannibalism firsthand, bought an eleven-year-old girl, handed her over to cannibals, and sketched her as she was murdered, dismembered, and eaten. (The episode may have inspired Joseph Conrad to write Heart of Darkness.) In 2011, the episode again came to light when Jameson ran an advertisement that glorified the company’s swashbuckling past. As a souvenir of his travels, Jameson arranged for the head of a murdered local man to be cut off, shipped home, and preserved by a well-known London taxidermist. It was displayed in Jameson’s home, where, Larson writes, it tended to “exude an unpleasant odour at certain times depending on the weather.”

Power inevitably enters the discourse around heads, and especially the heads of tyrants. For centuries, one of the most prized collectibles on the market was the head of Oliver Cromwell, which had a metal spike driven up its neck and out the top of its skull. Cromwell had been buried in state, but his body was exhumed after the Restoration, subjected to posthumous execution, and decapitated. His head was displayed atop Westminster Hall for more than twenty years, until a storm brought it down. As one story goes, the head was spirited away by a guard and vanished for decades. It turned up in the early 1700s in the London museum of the Swiss curiosity collector Claudius du Puy. When it fell into the hands of one Samuel Russell, an alcoholic comedian, it was apparently “tossed around and ‘treated incorrectly,’ leading to the loss of one its ears.” Counterfeit rivals emerged over the years, and the authenticity of the Russell head was never definitively established. It was finally buried in a secret location at Cambridge in 1960.

History’s beheaded include generals, nobles, suspected witches, and rank-and-file soldiers. By some estimates, 60 percent of Japanese remains found in the Mariana Islands after World War II lacked skulls. (Though other body parts were taken, too: FDR was apparently presented with a letter opener made from a Japanese soldier’s arm.) In 2012 Derrick Shaftoe found a footlocker in the attic of his Phoenix home. Inside was his grandfather’s collection of twenty Japanese skulls “labeled and marked with the location and date the man was killed.” Memorabilia dealers come across this kind of skull all the time; many are etched with inscriptions. In 1944, Life ran, as its picture of the week, the image of a pert American girl, pen in hand, writing a thank-you note to her boyfriend for the Japanese skull that lay on the table beside her.

Larson, an honorary research fellow at the University of Durham, has also coauthored a book about the Pitt Rivers Museum, at the University of Oxford, which is known internationally for its collection of ten shrunken heads. Several years ago, Ted Dewan, a children’s book illustrator, offered to donate his own head to the museum, promising, Larson writes, to “leave enough money to cover the shrinking and maintenance of his head.” The Pitt Rivers shrunken heads are part of a collection of some 300 skulls and skull fragments that are held by Oxford and displayed, according to the wishes of the museum’s founder, typologically. Closer to home, the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia counts among its treasures parts of Lincoln’s and Einstein’s brains, a collection of trephined Peruvian skulls, and several intact brains of murderers and epileptics.

Larson’s book describes the practice, in eighteenth-century France, of taking pills made from the heads of executed criminals to cure ailments of the head. “Skull moss,” made from lichens growing on the skull, was also sold for this purpose. These medicines were common, Larson writes, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when “the sale of ‘mummy’ — the remains of embalmed human corpses prepared and prescribed as remedies — thrived across Europe”:

Every part of the human body had a medicinal use, from the bones and blood to the skin and fat. There were various recipes for making “mummy,” which was described as a hard, black, resinous substance that smelled fragrant but tasted bitter. The flesh was repeatedly dried, and might be soaked in wine or sprinkled with myrrh until it darkened and ceased to smell. As usual, whole, young bodies were recommended, preferably those that had been executed and were free from disease. Some people recommended men who had red hair, because they were thought to have better blood. Mummy became so widespread that medieval shoppers were warned to avoid counterfeits and select only samples that were shiny black and smelled good, not pieces that were full of bits of bone and dirt.

As with shrunken heads, a cottage industry took hold: early anatomists found that “human fat and body parts could bring them useful extra income to fund their dissections.” Dissect to sell, sell to dissect; the logic worked powerfully in both directions.

If human remains can be administered for their salubrious effects, what’s to keep them from being brought back to life? Larson writes of a “chance discovery involving a steel scalpel, a brass hook and a pair of dissected frog’s legs in Bologna in the 1780s” that started the craze for “animal electricity” (a phrase, like “headhunter,” that has migrated very far from its source). The scene was the laboratory of Luigi Galvani, whose name gives us the word “galvanized.” He found that electrical charges administered to animal remains could “reanimate” them. Galvani’s nephew and “most fervent disciple,” Giovanni Aldini, toured Europe with homemade batteries, sometimes cutting off a dog’s head before attaching to it his galvanic probes “so that its teeth started to chatter and its eyes rolled in their sockets.” Word of these experiments reached Mary Shelley and her circle in Switzerland, and the result was Frankenstein.

Some eighteenth-century researchers thought that a head could remain conscious up to fifteen minutes after decapitation, horribly free to ponder its own condition. In 1971, a surgeon named Robert White, hoping to show the feasibility of head transplantation, successfully attached the severed head of a monkey to a new body. The resulting creature was, in Larson’s words, “dangerous, pugnacious, and very unhappy.”

Galvanism has given way, in contemporary quack science, to cryonics, the business of freezing humans for later resuscitation. When I was growing up, the only thing I knew about Walt Disney was that he had been frozen. It was a myth, but the story was so persistent that the Disney family finally spoke out against it in 2012. Ted Williams, the Red Sox legend, is apparently frozen in two pieces at an outfit in Arizona called Alcor Life Extension Foundation. His son, John Henry Williams, was supposedly planning to make a kind of superrace using the slugger’s DNA. CBS News, drawing on an article from Sports Illustrated, reported that

after Williams died July 5, 2002, his body was taken by private jet to the company in Scottsdale, Ariz. There, Williams’ body was separated from his head in a procedure called neuroseparation, according to the magazine.

The operation was completed and Williams’ head and body were preserved separately. The head is stored in a steel can filled with liquid nitrogen. It has been shaved, drilled with holes and accidentally cracked 10 times, the magazine said. Williams’ body stands upright in a 9-foot tall cylindrical steel tank, also filled with liquid nitrogen.

According to Frozen, a tell-all published by Alcor whistle-blower Larry Johnson, Williams’s head was propped in its container atop a can of tuna and was once struck with a monkey wrench by a rogue technician, littering the floor with “tiny pieces of frozen head.”

Larson’s book amounts to a history of — and, at times, an example of — morbid curiosity, which can never be morally quarantined from its obsessions. It explains why people have wanted to sever, collect, display, and shrink heads over the centuries. But the questions it raises about viewing these heads are perhaps more troubling. When the artist Damien Hirst had his picture taken at the age of sixteen next to a jowly severed head in the Leeds morgue, he crossed a line few would want to cross. But most people would be willing to see the image online, as I have, or seek it out when exhibited, as it was most recently in Walsall, England, and Qatar. It is hard to escape the feeling that every time someone clicks on frame 313 of the Zapruder film, or finds the autopsy photos of Marilyn Monroe, or looks at the video of the suicide of Pennsylvania State Senator R. Budd Dwyer, or checks out the Facebook page of a spree killer, a portion of the culpability transfers to the gawker. Many of these images make somebody, somewhere, rich. Hirst, Larson writes, “may well be the wealthiest living artist in the world.”

Representation presumes that we maintain sufficient distance from the object we’re viewing to observe and consider it. This distance is frustrating, which is why Hirst wanted to pose with the head, and why so many people find themselves examining the photo in a gallery or online. This type of monetizable voyeurism translates brilliantly to the Internet, and so it comes as no surprise to discover the role that beheadings have played in the Web’s history. In 2002, when Daniel Pearl was beheaded by Pakistani militants, the video of his execution spread widely online. Two years later, the beheading of American engineer Nick Berg by Iraqis became the most popular video on the Internet. Larson reports that on May 13, 2004, shortly after Berg’s killing, the top ten search terms in the United States were all related to Berg’s execution:

nick berg video

nick berg

berg beheading

beheading video

nick berg beheading video

nick berg beheading

berg video

berg beheading video

‘nick berg’

video nick berg

There is a moral gulf between killing an innocent man and watching a video of his killing, but it is not clearly broader than the gulf between murderers and the tourists who, once upon a time, bought tsantsas. And often the terms are identical: “savage” crops up often in discussions of radical Islam. A few years ago, a group called the American Freedom Defense Initiative wanted to put signs in the Boston subways reading in any war between the civilized man and the savage, support the civilized man. support israel; defeat jihad. The Boston transit authority rejected the sign, a decision that was backed up by the courts. Yet it was mainly “civilized men” who made the beheading videos an Internet phenomenon.

The current wave of brutal decapitations in the Middle East makes reading this book, which is often darkly joyful in its descriptions of hideous violence, an uncomfortable experience. What allows us to think of heads as things separate from persons, and therefore from suffering, is usually their otherness: babies’ heads float in formaldehyde a century old; Amazon warriors, like Japanese soldiers, are “savages.” A mist of anonymity or infamy hangs over most of the heads that make it into cultural circulation.

The videos and stills of the murders of James Foley and Steven Sotloff, some of them posted by the executioners, confront us with the spectacle of people we know or could easily know, people who were innocent of any crime, killed in the most exploitative way imaginable, against the desolating backdrop of sand and wind. The week Sotloff was beheaded, the Internet was up in arms about the invasion of Jennifer Lawrence’s privacy after her hacked nude photos made it online. But on those same days, more than double the number of people searching for those photos performed searches related to Sotloff, with “beheading video” among the top hits. John Podhoretz, in the New York Post, excoriated President Obama’s “inaction” against the Islamic State in a column printed alongside the clearest image I have seen of the moments before Sotloff’s murder, the executioner’s knife visible in his hand. If I hadn’t read Severed I would have been much more confident in dismissing these images as instruments of fringe politics, fed to people who believe their fury to be different in kind from that of the people doing the killing. But Severed makes it clear that there are no beheadings without an audience, and the Internet is the biggest human audience ever assembled.