Toni Morrison’s novels — a formidable shelf of eleven by now, as the author settles in to her mid-eighties — have all been catholicons, correctives to the canon. That strong, sensuous diction — always hers even when it is also a character’s — is merely the outer wrapping for rage, for exhortation. In this way, her work resembles the Bible, if the prophetic cadence were cut with straight talk, skewed adage, and jive. Hers has been a Protestant calling, though Morrison converted to the Church of Rome at the age of twelve.

Morrison’s other, perhaps more influential, apprenticeships were to Tolstoy and Austen. But unlike many of the famous black novelists — the men — of the generation before hers, she never regarded their olden covers as limiting. White Lit, to Morrison, was merely another option, to accept or reject alongside the African fables and trickster lore she was raised with; no life so chafes against the character arcs of the European novel as that of a black woman. Tolstoy’s and Austen’s characters were after closure: marriage. But the desires of the Gullah flying men (who inform Song of Solomon) and Br’er Rabbit (who informs Tar Baby) are ambiguous, open-ended. It was Morrison’s task to redeem those magical figures from their perversion by the Uncles (Tom and Remus) and even from the techniques of Ralph Ellison, whose every folksy snippet is kept out of the flesh of his book and remanded to dialogue. Morrison’s characters — Sethe the fugitive slave in Beloved, the besieged nuns of the convent in Paradise — are doomed from the first page, and between that and the last seek grace.

LTS III, a charcoal, pastel, and marker drawing on board, by Toyin Odutola, whose work was on view last May at Jack Shainman Gallery, in New York City © The artist. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York City

Morrison’s eleventh novel, God Help the Child (Knopf, $24.95), unfolds in a funereal procession of monologues. But the oral tradition can seem buried here, if only because the setting is contemporary and the sentences teem with Diet Cokes and PlayStations. This might be Morrison’s point: familiarity — verisimilitude — has always allowed the novelist to smuggle in myth. Memory helped her do this with her own century, and research with the prior century, which haunted her. Now our reigning Nobel laureate leaves behind Jim Crow and America’s “peculiar institution” to make a book from modern life.

Or from the life of Bride, the mononym of Lula Ann Bridewell, who “dropped that dumb countryfied name as soon as [she] left high school.” Leaving her youth behind also means leaving behind the woman she called Sweetness, who never let Bride call her Mother: Bride was too black to be loved — “Midnight black, Sudanese black” — and this pigmentation enraged Sweetness’s husband, Louis. Both parents were “high yellow”; Sweetness must’ve been fucking around.

Bride is loved by her mother only once: when the seven-year-old Bride goes to court to testify against Sofia Huxley, a kindergarten teacher who might or might not have abused her. Fifteen years later, when Sofia is paroled, Bride — now a successful cosmetics designer, dressed all in vestal white and driving a Jaguar — is at the prison gate to meet her. Bride tries to give her a ride, but Sofia refuses. Bride follows Sofia’s taxi to a motel and tries handing the woman envelopes stuffed with $5,000 cash, a $3,000 Continental Airlines gift certificate, and a Louis Vuitton bag containing a promotional box of her own product, YOU, GIRL: Cosmetics for Your Personal Millennium. Sofia reacts by beating the hell out of her. Bride, badly injured, unwilling to call the cops, and unable to call her estranged boyfriend, Booker, instead calls her friend and co-worker Brooklyn, a dreadlocked white woman who comes to care for her and to parse her lies. Bride says nothing about Sofia, and explains her condition by concocting an attempted rape. If Brooklyn has her doubts, she keeps her own counsel, because while Bride recovers — with a face too battered to be useful to a makeup firm — Brooklyn manages YOU, GIRL, and rises through its ranks.

That, at least, is the mundane plot, after which Morrison ushers in the supernatural and lets her hair down, literally. While convalescing, Bride finds that she’s lost her pubic hair. Her body is changing — aging is reversed; her ear piercings fill in; her breasts go “completely flat, with only the nipples to prove it was not her back.” At the same time, she resumes her affair with Booker, who has his own regressions to deal with. The decline of his aunt Queen motivates him to revisit the murder of his brother, Adam. Queen dies, and Bride, the child-woman, becomes pregnant. Read these reversions as you will: the trappings of adult success are childish (Morrison has wonderful takes on vacationing, and on smoothies); the falsehoods of childhood become the truths of adulthood; our bodies record the slights of our minds; only the unborn and the dead can be forgiven.

Youth, an estate misremembered until it becomes an estate superintended, is, in every way, The Folded Clock (Doubleday, $26.95) — which is also the title of a new diary by Heidi Julavits. Its pages hold the promise of a tell-all. Here is everything you need to know about the author, from her clothing and food preferences to her abortion, her sex habits, and her marriage (to the novelist Ben Marcus) — everything, that is, besides her four sly novels (including The Vanishers and The Uses of Enchantment) and her founding editorship of The Believer, which go unmentioned. Instead we have two kids, including a daughter, whom Julavits introduces to Egyptian hieroglyphs at a museum. One of the glyphs, Julavits explains, is based on the shape of a folded cloth, which her daughter mishears as “folded clock.” Julavits corrects her, but “pickpocket[s] her accident.”

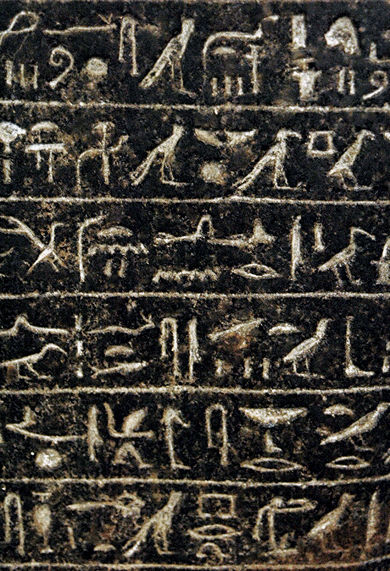

Detail of a hieroglyphic inscription on a block statue of Amenhotep, circa 1400 b.c. © Album/Art Resource, New York City

Youth is something to pilfer; from the mouths of babes come titles, and from their precocity come careers, or so Julavits once thought. Asked by a geriatric audience, in a different scene, about her origins as a writer, she cites some lore: when she was a child, her father took her to the mall — that other museum — to buy the family’s first color TV. He also bought her a diary, after she promised to make entries regularly. Julavits, in her account of this in the book, shrugs off the banal dichotomy — the mind-slaughtering TV versus the mind-sustaining page — by quoting her first entry: “Today I woke up and watched TV.” Subsequent entries are just as blah: “Today at school I got a 100 on my math test and I finished my science assignment. I am all set for my literature report but I’m really scared.”

Revisiting that diary to confirm her account, Julavits finds that the prose doesn’t suggest the mind of a future novelist but that of “a future paranoid tax auditor.” The Folded Clock is her attempt, decades later, to redeem herself, and even to redeem the pressures attendant on childhood — the pressure only adults can impose on childhood — as a time of fuller, or deeper, experience.

Julavits takes us through two years of teaching (at Columbia, which isn’t named), hanging with friends and family in coastal Maine (where she “summers”), and avoiding writing during a writing fellowship in Berlin. But if everything seems orderly at home, or at her multiple homes, it isn’t orderly on the page: the entry for March 3 gives way to the entry for July 29; July 18 is next, then August 2; there are no years marked. Throughout, awareness means self-awareness, and consciousness of others means consciousness of how Julavits is perceived. Her visits to libraries invariably lead to observations of other visitors, or of her own moods; books are discussed only in terms of their placement in bookstores. The body becomes the locus of all nonliterary neuroses: health is monitored on the nanolevel and becomes a matter of deciding between consuming or not consuming some berry, nut, or seed; hydration is a must.

In chronicling her privileged life with a pretense of honesty — or transparency — Julavits is taking the great millennial risk: the risk of being “unlikable,” which is a contemporary American word for “human.” Then she goes beyond that, to the verge of becoming unlikable to herself. That’s where her book — a diary written for an era that has consigned fiction to the world of children or Young Adults — becomes aching, and solacing. Her four-year-old son suffers an illness, or possibly a “misery fugue state,” that makes him weep. Julavits rubs his back to calm him, but also to calm herself; she hates wasting time like this, and might as well be “sharpening a knife”:

I tried to think of how this motion might, in the future, come in handy. I thought, If my son dies, I will sit at the shore, and swoop my hand like this back and forth over a smooth rock that has been warmed in the sun and feels humanlike as a way of remembering him. Then I thought this was melodramatic and gruesome. I thought instead: Maybe I’ll write a story in which a character’s son dies, and she could, as a means of coping, go to the shore and do this. Then I thought this was stupid. I thought instead: I must remember to do this when I am seventy. I must remember to find a rock that feels exactly like my son’s four-year-old back. I must remember to close my eyes and imagine that I am me again, a tired mother trying to teach herself how to miss what is not gone.

“How to miss what is not gone”: This is what we can learn from Silvina Ocampo.

Born in haute Buenos Aires in 1903, dead in 1993, Ocampo deserves a posterity distinct from that of her husband, rival, and love of half a century, Adolfo Bioy Casares, whose early collaborations with Borges were published by Silvina’s sister Victoria, founder of the journal (and publishing house) Sur. Two major books of Ocampo’s have finally found their way north and into English: a collection of stories, Thus Were Their Faces, translated by Daniel Balderston (NYRB Classics, $17.95), and a collection of poems, silvina ocampo, translated by Jason Weiss (NYRB Poets, $14).

The stories are feverish, cruel, and wry, set among the surrealisms of puberty, disability, and precarity. “The Clock House” begins with a bout of spine-touching. A hunchbacked horologist named Estanislao arrives at a party, and his hostess rubs his hump for luck. This is the beginning of the humiliation, or festivities, at which he seems both unwelcome — he belongs to a lower class — and the guest of honor. The guests constantly show Estanislao their broken watches, which he promises to fix at no charge. The child-narrator understands everything, and nothing.

An adult narrates “The Fury,” the tale of his courtship of a nanny whose ward is a feral or autistic child who relentlessly beats a drum. The nanny takes the opportunity of a rendezvous to recount how she once terrorized a childhood friend with animal corpses. Later, ashamed of her behavior, she apologized by presenting the girl with a living fish and monkey, which the friend allowed to starve.

Other stories involve children letting plants die; an adult who shops for childhood toys in junk shops; a young girl told to peep through a keyhole (she enjoys the mystery until she realizes she’s giving pleasure to the man on the other side of the door); an adolescent who can’t tell whether he raped someone or the sex was consensual; two kids in a mansion, who, locked away from the adults, build their own mansion out of matches and then burn everything down; an eight-year-old who kills another eight-year-old.

Ocampo’s poems owe their themes to these fictional milieus, and their pitiless concision to the poets she translated (Baudelaire, Dickinson, Verlaine). Seven collections have been amassed here, as well as a selection of miscellaneous and previously unpublished poems. The first two collections, Enumeration of My Country (1942) and Metrical Spaces (1945), feature sequences of epitaphs: for a Tree, a House, a Trapeze Artist, a Jealous Woman, a Lover, a Poet, and an Aroma. The last doesn’t linger, but then “neither does that person exist anymore / for whom I was in secret destined.” Later collections extol the streets, squares, and courtyards of “old” Buenos Aires — the old for Ocampo is always at the edge of the lost — along with mythology and the story of Cain and Abel, the biblical episode that most transfixed her. “Childhood Home,” published in 1962, likens the “design and inner workings” of the house that the speaker grew up in to that of “a clever transparent watch.” Visitors come and go, but their faces are forgotten. The daughters of the visitors envy her shoes, which, for the narrator, “had no soul.” She prefers, she says, to be upstairs, with the servants:

I love only the bread that tasted like burlap,

sugar from a bag, not from the bowl,

and on perfect afternoons the noise of the ordinary

teacups upon the marble and the houses

that decorated the soup dishes in the kitchen,

and that washbowl with wisteria flowers

where I would furtively wash my hands

and murder my favorite dolls.