In the final seconds of Wolf Hall — the six-part BBC adaptation of Hilary Mantel’s best-selling novels of high-stakes intrigue at the court of Henry VIII — the camera lingers on the terrified face of a man who has just achieved total political triumph. The man is Thomas Cromwell, Henry’s chief minister, a blacksmith’s son whose improbable rise to power has just been capped by the latest of his machinations on behalf of his monarch: the execution of Anne Boleyn, Henry’s second queen, on trumped-up charges of adultery and treason. (Her real crime, as everyone knew, was her failure to provide a male heir.) Never mind that Cromwell had engineered the marriage to Anne in the first place. The perfect underling, he smoothly bends his ethics to his master’s whims.

Fresh from Anne’s execution, Cromwell seems to float (the scene is shot in dreamlike slow motion) down the length of a magnificent gallery in the palace toward a beaming Henry, who awaits him with arms outstretched in jubilation. As the king enfolds his minister in a bear hug, we see Henry’s exultant expression; he’s got what he wanted at last. Then the camera sneaks behind Henry’s back to give us a glimpse of Cromwell’s face, the lower half of which is pointedly obscured by the king’s massive arm: the minister is being literally as well as metaphorically smothered by the autocrat. The percussion-heavy music builds to a climax, and we see Cromwell’s green eyes staring horrified into space — into the future. At this moment we realize what he has just realized: from the heights of success, the only direction he can go is down. As, indeed, was the case. Within a few years it was Cromwell’s own head that rolled, after an attempt to orchestrate yet another marriage for Henry fell apart.

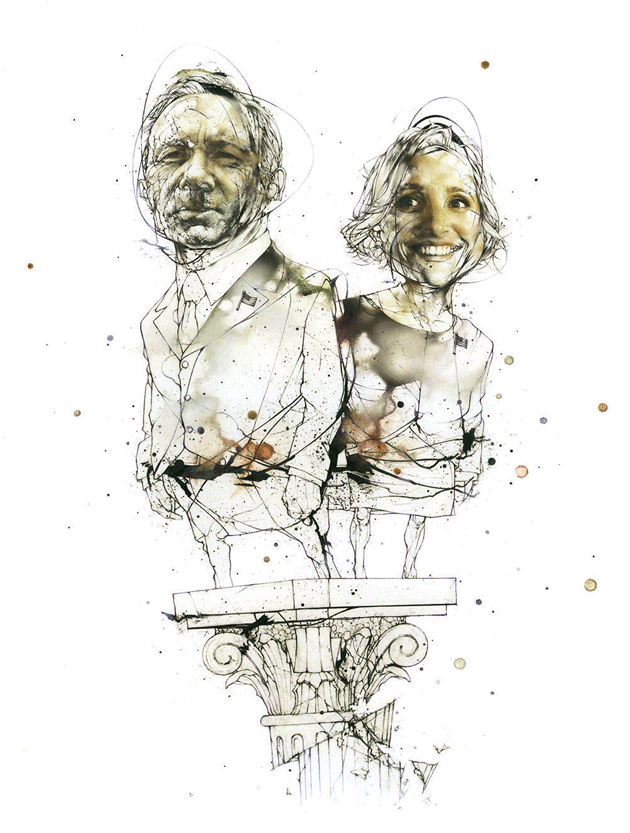

It was hard not to think of the perils of political success, and of the pleasures of political drama, as the recent television season came to an end — and the frenetic jockeying for the 2016 election began. Two of the great successes on TV this year have been shows about American presidential politics; in each, an underdog rises to power as relentlessly — and Pyrrhically — as Cromwell did. One is a drama: House of Cards (Netflix), about the revenge-fueled ascent of Frank Underwood, a Machiavellian congressman from the South, whose good-old-boy affability conceals a heart of ice. (The show’s first episode opens with him killing a neighbor’s dog with his bare hands: that’s how cold he is. When he pushes a pesky journalist in front of an oncoming subway train in the next season, you don’t even blink.) At the beginning of the first season, Underwood is passed over for a cabinet position he covets by the president he helped get elected — a betrayal that inspires him to concoct a vengeance of fantastic complexity. Among other things, he finesses a gubernatorial election to force the vice president to resign, allowing Underwood to replace him, and subsequently creates a scandal that causes the president to leave office. By the third season, which was released in February, Underwood has lied, cheated, cajoled, and murdered his way into the Oval Office.

If House of Cards holds up a cynical, only slightly distorted mirror to the ugly conniving that makes power possible, the other big hit about a presidential aspirant, the sourly comic Veep (HBO), satirizes the way in which ineptitude often seems to be rewarded in politics. Like Frank Underwood, Veep’s Selina Meyer is an underling who finds herself in the White House at the beginning of the new season (the show’s fourth, which ended in June). This being a comedy, Selina’s means of ascent are more or less the opposite of Frank’s: after three seasons of bumbling, babbling, and wisecracking herself into total irrelevance, she becomes president by pure accident, after her predecessor unexpectedly resigns. Thus far, she shows no sign that she’ll acquire any more gravitas as president than she had as veep. “Maybe we can put Afghanistan on eBay,” she tells her aides in the season’s first episode.

As different as these series are, their protagonists have both come to face what you might call the Cromwell problem: what happens when you finally get the power you’ve coveted for so long? Even more interestingly, the series are now facing that problem themselves. When the engine of your drama has been a character’s scheming for power, what happens when he or she finally gets it?

The drama of the manipulative subordinate has been satisfying audiences since the beginnings of Western theater — to be precise, since the spring day in 458 b.c. when Aeschylus’ Oresteia premiered in Athens. Like House of Cards, each play of the trilogy traces the course of an elaborately plotted revenge by someone who has been slighted or relegated to the political and social margins — someone who, during the course of the drama, seizes power and then uses it to punish personal and political enemies. (Horribly.) As the first play begins, Clytemnestra, the queen of Argos, still outraged that her husband, Agamemnon, sacrificed their daughter at the start of the Trojan War, has been waiting ten years for the fighting to end so that she can kill him at the very moment of his triumphal return. This she does, and that revenge plot sets in motion another. In the second play, the couple’s son, Orestes — rightfully the king but long since rusticated by the shrewd Clytemnestra — infiltrates the palace incognito and slays his wayward mother and the lover with whom she usurped the throne. That murder, in turn, invites a vengeful pursuit in the third play by the supernatural Furies, who drive the boy-killer to madness. The plot of each drama takes the form of a literal plot — to murder, to punish, to avenge — on the part of an outsider who by the end of the play finds him- or herself the powerful person now being plotted against.

The appeal of this narrative is hardly restricted to the theater: the entire second half of Homer’s Odyssey is little more than an elaborate revenge plot enacted by someone who, reduced to powerlessness by circumstance, slowly, violently works his way back into power. But the story line has proved particularly irresistible to dramatists.

In part, the popularity of tales about the ruthless (or, in comedy, hapless) acquisition of power has to do with our experience as citizens: these narratives reflect what we know, or at least suspect, to be the distasteful and often illicit realities of politics and power. But there is, too, a deeper, psychological element. It’s surely significant that many of the characters who have consistently seized the cultural imagination — and, whether we like to admit it or not, our sympathy — are twisted, wounded schemers: Clytemnestra and Richard III, Iago and Frank Underwood, all of whom share the same psychological DNA. (Andrew Davies, who wrote the 1990 BBC series on which House of Cards is based, acknowledged that he modeled the main character on Shakespeare’s Richard.)

It’s not hard to see why. Because we’ve all felt slighted in one way or another, because we’ve all had aspirations to rise to the top, these characters, with their outlandish bids for control, appeal to us far more than do the smug leaders, the complacent husbands, and the clueless consorts whom they ultimately topple. (It’s no accident that in both House of Cards and Veep, the presidents replaced by the protagonists are bland ciphers: nobody identifies with them.) There’s a point in Richard III when the nephew of the hunchbacked king — one of the “little princes” who are later murdered at Richard’s command — slyly mocks his uncle’s deformity. “You should bear me on your shoulders,” the boy smirks, knowing full well that those shoulders can’t carry anyone. Who in the audience, put in mind by that taunt of some past injury, some half-forgotten teasing, doesn’t know what it feels like to want to strike back?

The striking back is the engine of the dramatic fun. Just as our identification with the conspirator’s wounds provides a complicated pleasure, so, too, does the chillingly methodical vendetta, elaborated from scene to scene, provide a darker satisfaction — replicating, in the safe space of fiction, the inventive fantasies of vengeance in which most of us have occasionally indulged. The more elaborate the ruse, the better: hence the pleasure of Underwood’s ascent, which plays out on the dramatic equivalent of a three-dimensional chessboard. A memorable conceit of Rowland V. Lee’s Tower of London (1939), which was partly inspired by Richard III, gave arresting if rather campy visual life to this brand of revenge. Lee’s Richard has a set of little dolls that he keeps in a secret cabinet in his chambers: each represents a relative or rival who stands between him and the throne. As the drama unfolds and he dispatches this or that sibling or nephew — by drowning them in barrels of wine, by more overtly violent means — he plucks a doll from the cabinet and tosses it into the fire.

The formula works just as well for comedy. Ten years after Tower of London, Ealing Studios took what was essentially the same plot and turned it into brilliant farce. In Kind Hearts and Coronets, the dispossessed scion of an aristocratic family inventively eliminates every relative who stands between him and the dukedom he seeks. (All of his rivals, from suffragettes to big-game hunters, are played with gleeful relish by Alec Guinness.)

That the conniving outsider is so central to tragedy and comedy alike should come as no surprise. For Aristotle, in the Poetics, intrigue and theater were connected at the genetic level. In that treatise, the philosopher identified plot as the most important element of a good drama; and a plot, he went on, consists of two complementary trajectories. First, there must be a “complication” — the Greek word is dêsis, which means a “binding” or “tying up in a knot.” Then there has to be a “resolution,” or lysis — a “loosening” or “untying.” (The concept persists in our term “denouement,” which literally means “unknotting.”) Hence drama isn’t really drama without scheming — without the ornery, complicating subterfuge at which resentful second bananas are so naturally adept.

This is why I worried about Veep and House of Cards when their most recent seasons began. Now that the mechanism that drove the shows — the striving by the main characters to raise themselves above what the foulmouthed Selina Meyer bitterly refers to as the “shitty experience” of being outside the circle of power — has achieved its end, where could they go?

I suspect that Veep has a better chance of enduring. True, Selina Meyer’s will to power and contempt for other people are as absolute as Underwood’s; the viciousness with which she denigrates her most devoted aide during an argument in Season 4 makes you forget, momentarily, that you are watching a comedy. (“What do you think you are?” she sneers. “You are unimportant, okay? . . . You are a middle-aged man who sanitizes my tweezers.”) And yet the incompetence of the people who surround her — in the latest season, her aides provide her with the wrong draft of her first big speech to Congress, and she finds herself staring at a teleprompter that says future whatever — acts as a kind of structural guarantee that this show will go on. Humiliation, it’s worth remembering, is at the root of comedy: all the bungling keeps Selina humble — always striving, always struggling, no matter that she now, ostensibly, has total power and authority. And the striving, as Aristotle understood, is what moves drama forward.

But what of House of Cards? I’ve been a fan since the show began: for me, as (I suspect) for millions of others, there’s a kind of relief in watching a political drama that mirrors the tawdriness of real-life politics even as it provides a Day-Glo escape from them. It’s been hard, though, not to notice a note of everything-but-the-kitchen-sink desperation creeping in to the plotting this past season. The story lines have yo-yoed from diplomatic crises to the president’s flirtation with a handsome young writer, from grandstanding Russian autocrats to jailhouse suicides by gay-rights advocates. But where’s it going? Surveying this erratic landscape, it occurs to you to wonder whether, now that the deliciously nasty arc of Frank’s ascent is complete, the show you’re watching isn’t becoming just a meaner version of The West Wing.

Or worse. In the final scene of Season 3, the greatest crisis facing President Underwood is that his steely wife may be leaving him. Was this, in the end, what all the conniving was for — to end up in a prime-time soap? Not for the first time in history, politics, or show business, the greatest danger of all may be success.