When I was eight years old, in 1966, during a holiday with my parents, I traveled to Heathrow Airport for the first time. The reason I put it so clumsily is that we weren’t flying anywhere. We were spending a week in London, and one morning we went out to see the airport and the planes coming and going. It was just like visiting the Tower of London or Buckingham Palace, as we had on other days. Instead of being a point of departure, the airport was a destination and attraction in its own right. I had to wait fifteen years, until I was twenty-three, before I flew on a plane. My parents both died in 2011 without ever taking a flight.

In the Sixties and Seventies, air travel was perhaps no longer the exclusive preserve of a tiny elite, but the glamour of the “jet set” — whoever they were — was near its peak. The threat of terror was not so pervasive that an ill-judged joke could put an entire terminal on lockdown. The contrast with today is brought out powerfully in a scene from 1975 in Terry Castle’s memoir The Professor. Castle describes an unorthodox interview for a fellowship that takes place at Sea-Tac airport and ends with her and her interviewer sneaking around a corner to get wildly stoned. Consider also the climax of Bullitt, in which Steve McQueen pursues his suspect onto — and off — a plane at SFO. At one point, McQueen asks someone to get hold of “the security guard.” Singular. It’s fiction, granted, but the ease with which the chase moves airside and back is a not implausible reflection of the lax realities of the day.

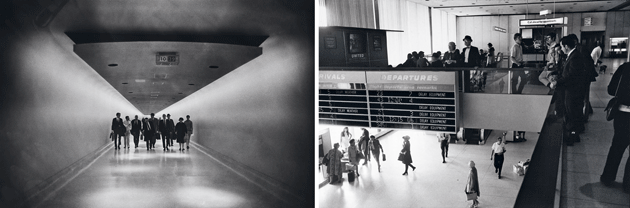

The most important documentary record of American airports in the transitional phase between exclusivity and the present era of comfortless democratization is by Garry Winogrand. Actually, we could substitute almost any word for “airports” in the preceding sentence — “suburbs,” “cars,” “shops,” “clothes” — and it would still hold true. Through his insatiable eagerness to photograph, Winogrand became a one-man archive of the social landscape of the Sixties and Seventies. (The airport work was posthumously published in 2004 as Arrivals and Departures.)

The earliest U.S. airports were designed to look conservative and old-fashioned in order to reassure nervous fliers. By the Sixties, however, they gleamed with the sleek confidence of modernity. They became as emblematic of their age as railway stations were of nineteenth-century Britain. The long walkways beckoned like the promise of the space age itself.

But the situation is, as always in Winogrand, more complicated than that. Those same walkways, like the one at LAX that Lee Marvin walks down with such purposeful menace in Point Blank, often had an atmosphere of shared alienation. One image in particular seems akin to Paul Strand’s famous 1915 photograph of people hurrying to work on Wall Street. Strand described the windows lining the street as “a great maw into which the people rush.” His people are heading left, out of frame; Winogrand’s are striding toward us. In a few years they will become us — and vice versa. Together we will be condemned to an endless web of connecting flights, doomed to wander DFW or some other place we never wanted to visit, simply because it’s a transit hub. Departing passengers will be funneled into a plane and emerge hours later in a place that is both entirely different from and pretty much the same as the one they have left.

This is the now-familiar environment and experience described by Marc Augé in his book Non-Places: An Introduction to Supermodernity. Appropriately enough, a Winogrand picture was used on the cover of the first English-language edition: a vast aircraft whose face — with the cockpit windows as eyes — is pressed up against a departure lounge, like a giant version of the animals he photographed in zoos.

The lure of the future proved problematic in another way too: it accelerated the speed at which airports would start to look old. Some of the terminals at JFK now look as worn out as a pickup stacked on cinder blocks. At various times different airports held the lead as the largest, busiest, most efficient or technologically advanced, but no sooner was a new paradigm of airportness established at a particular site than it became overcrowded, inefficient, and old-looking. Winogrand’s style — he said that he liked to work “in that area where content almost overwhelms form” — was perfectly adapted to exploit this tension.

The evolution of the fashions of commercial flight likewise reflects the tension between tradition and modernity. Pilots dress conservatively, in a style very obviously derived from a naval heritage. This has remained reassuringly unchanged. But the outfits of flight attendants tell a different story. As envisaged in the films of the Sixties, air travel and space travel shared a wardrobe, though there was a chicken-and-egg quality to the relationship. Airlines wanted their employees to look futuristic, so the designs were informed by fictive visions of that future — but those visions were themselves extrapolations from existing fashion.

As for the passengers . . . well, at JFK a couple of years ago I bumped into a very smartly dressed Phillip Lopate (born 1943), who explained that he belonged to a generation that dressed up when they took a flight. Winogrand captures this fluid collision of the casual (a woman in curlers!) with the kind of uncomfortable elegance that must have seemed essential for boarding a zeppelin. Being Winogrand, being the man who titled a book Women Are Beautiful, he is also alert to glimpses of romantic potential that are doomed, in this zone of constant comings and goings, to be no more than fleeting — and that cry out, as a consequence, to be permanently preserved on film.

“Houston, 1969,” by Garry Winogrand © The Estate of Garry Winogrand. Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco “New York, 1968,” by Garry Winogrand © The Estate of Garry Winogrand. Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum, transfer from the National Endowment for the Arts

In other words, Winogrand found in airports the very same dramas that he stalked obsessively in the streets of Manhattan. The difference is that the movements, gestures, and interactions were altered by a space designed specifically to create certain situations (being separated from or reunited with a loved one) and to facilitate coping with all the consequences of those situations: lost luggage, missed connections, etc. As such, his pictures are replete with frustration, disappointments, and boredom. A display board, for example, lists one flight after another as delay equipment.

When Robert Doisneau came to England he was disappointed by what he found — or failed to find. On the Continent, he said, when people missed a train they threw up their arms and made a fuss. In England, they sat down. Winogrand didn’t need the gestural operatics that Doisneau missed. Along with everything else he was one of the great photographers of people sitting; he captured them stranded in some void as if that were the defining experience of their life.

In Winogrand’s time, the experience of delayed flights, though inconvenient and infuriating, had yet to acquire the cumulative tedium — the terminal lack of velocity — with which we are all now overfamiliar. Delay, boredom, and frustration had not been permanently imprinted on the idea of travel. In Winogrand’s pictures both excitement and dread still hang in the balance. And he was on hand to take the second most joyous picture of someone stepping off a plane. The first, of course, is the wonderful — and ultimately heartbreaking — image by Slava Veder of Lieutenant Colonel Robert L. Stirm being greeted by his family at Travis Air Force Base, in California, on March 17, 1973, after spending five years in captivity as a POW in Vietnam. That was an exceptional and newsworthy event. But when Winogrand saw the fellow with the beaming face holding a sign that said welcome to california jane, he captured the eternal promise of flight and of the American West in a single moment. I’m amazed the picture hasn’t been blown up and installed permanently at LAX.

The twenty photographers whose images are collected in this portfolio update Winogrand’s researches and expand our view to include airports all over the world. The assignment was simple: turn a travel day into a working day, documenting the terminals, waiting rooms, and checkpoints they passed through during the month of April. Remarkably, many of their pictures seem like prints from a newly discovered set of Winogrand’s negatives. Others show the effects of the now inescapable security regime. If airports were once places to which one made occasional and thrilling visits, now many of the people encountered in them have the look, in prison parlance, of “lifers.” Arrivals and departures have given way to a perpetually transient residency.

Except for a few hellish enclaves, smoking has all but disappeared. And even though airports remain places where you still see banks of pay phones, the human dances they generate — much loved by Winogrand, who was always ducking into phone booths to check his answering service — have been depleted to the point of near extinction. In their place we have an ensemble cast of soloists on cell phones. People are present physically but are conversationally and psychically elsewhere: the non-place is now inhabited by the non-present. These two trends — less smoking, more phones — are related. Whereas the first thing people used to do after getting off a plane was to reach for their cigarettes, now they reach for their phones. As Jonathan Franzen has observed, we have gone from “nicotine culture to cellular culture.”

“Untitled, ca. 1972,” “Los Angeles, 1964,” and “Los Angeles, 1964,” by Garry Winogrand © The Estate of Garry Winogrand. Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

And yet, for all the small, incidental changes (and photography, more than any other medium, is predicated on the incidental), what is striking is the way that the essential human dramas remain unchanged. “Dramas,” plural, because — and this is the great thing about both Winogrand and the photographers represented here — so much is going on. Of all the things that are superfluous to a photographer, a knowledge of or interest in the human condition is close to the top of the list; what counts is an endless fascination with the arrangement of human faces, bodies, and clothes and the circumstances in which these humans find themselves.