At the beginning of Mission: Impossible — Rogue Nation, the top-secret Impossible Mission Force (I.M.F.) is disbanded after a congressional investigation deems it too reckless. Now Ethan Hunt (Tom Cruise) and the rest of the I.M.F. must work outside the law. But Hunt never worries. He’s a man who can hold on to the side of an accelerating airplane loaded with nerve gas and suffer no damage beyond his hair parting weirdly in the wind, which leaves him looking vincible and a little bit Amish.

The brilliant conceit of Rogue Nation is that the structural characteristics of the independent I.M.F. are also those of the criminal network it is battling, the Syndicate. Both answer to no government, and the public knows about neither. The head of the Syndicate is Solomon Lane (Sean Harris), a former MI6 agent; Lane employs (or deploys, it’s fuzzy) dozens of operatives around the world, each one a former intelligence agent who is believed by his government to be dead but is not actually dead. The missions of the Syndicate — blowing up factories, disappearing planes — are, like the missions of the I.M.F., made to look like accidents or the work of others. By not taking credit for their acts, the Syndicate is not, Lane emphasizes, a group of terrorists: their method is not terror but illusion.

We never learn what all these missions are intended to bring about. It’s simply presented as a given that the goals of the I.M.F. are good and that those of the Syndicate are bad. Lane isn’t even into luxury — he doesn’t want Dr. No’s private island. He’s just a guy who wants to manage world events, like everyone else in the film.

The movie is, in part, an exploration of the ethics of extralegality, of going rogue: if you and your enemy are both breaking the law, who will judge what’s wrong and what’s right? For Hunt’s team, the answer is uncomplicated; they are motivated mainly by loyalty. It’s an emotionally appealing idea, suggesting that if you always act to protect your friends, less stuff in the world will explode and fun adventures will ensue.

To prevent Lane from enacting his new world order (not that we ever know what that might look like), the good buddies in the I.M.F. eventually decide that they need to capture and sedate the British prime minister. Only the prime minister can speak the passphrase that opens some very important, triply locked files. The passphrase proves to be quite moving. It’s a quote from a Rudyard Kipling poem, a poem that schoolboys of the past often learned by heart, before Kipling became confused in the Western imagination with a desire to own and rule the world: “If you can keep your head when all about you / Are losing theirs and blaming it on you, / If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you.” The passphrase doesn’t include “and blaming it on you” or the next line in the poem: “But make allowance for their doubting too.”

At the end of the mission, Hunt offers the director of the CIA (Alec Baldwin) a pretty story to describe what happened, which of course is not what really happened. Since the story casts the CIA as the hero, the agency is usefully willing to report the lie back to Congress and testify in defense of the I.M.F. (There is an echo here of what Edward Snowden described as his “breaking point”: the testimony that James Clapper, the director of national intelligence, gave to Congress in 2013, when he claimed that the NSA wasn’t collecting data on millions of Americans.) By the end of the movie, the I.M.F. is legal again, as are its secret, unchecked missions.

Not that we ever forget that this is just a movie — one of five movies in a multibillion-dollar enterprise. A memorable moment in Rogue Nation comes at the end of a long chase scene in Morocco: Hunt is pursuing a woman on a motorcycle, Ilsa Faust (Rebecca Ferguson), whose allegiance is as yet unknown. The chase ends abruptly when Faust gets off her motorcycle and stands in the middle of the road, causing Hunt to stare, swerve, and crash.

It seems appropriate to add here that the time signature of the original Mission: Impossible theme song was 5/4; at various points in Rogue Nation, it’s been altered to 4/4. This is, some say, because the 4/4 beat is easier to dance to.

Acting outside the law in service of a higher law is a long-standing trope, but it appears to be going through a renaissance. Film and television screenwriters have for the most part proved distinctly uninterested — or so interested that they feel the need to disguise their interest deeply — in dreaming up Snowden or Chelsea Manning figures. Instead we have heroes like Hunt, who fight against transparency and accountability. It’s no surprise that the government ends up embracing him all over again.

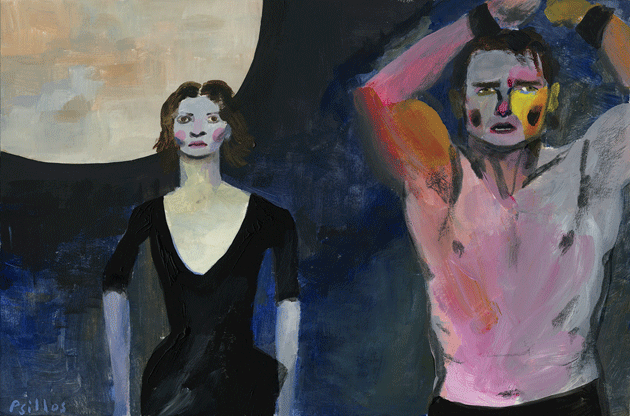

The most enduring story of extralegal heroism I know of is Sophocles’ Antigone, in which a woman breaks the law to give her dead brother a proper burial, even though doing so ensures that she will be put to death. The Antigone production that had its U.S. premiere at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in September is directed by Ivo van Hove and uses a new translation of the play by Anne Carson. Antigone is played by the film actress Juliette Binoche, who infuses an essentially static role with energy; Patrick O’Kane, who plays Creon, the king of Thebes, magnificently highlights his maddening childishness while still making his painful late insights feel profound.

A refresher course: Antigone is a child of Oedipus’ incestuous marriage to his mother — she is a living embodiment of the violation of law. At the opening of the play, her brothers, Eteocles and Polynices, have died in battle, the former while defending Thebes, the latter while attacking it. Creon decrees that Polynices is a traitor and may not be mourned or buried. Antigone buries him anyway, winning the sympathies of much of Thebes and a death sentence from Creon, who is also her father-in-law-to-be.

The van Hove production is set in a kind of everytime; instead of using the playful, modernized translation that Carson published in 2012 as Antigonick, he commissioned her to do a more straightforward version. The costuming — dark suits, pencil skirts — is slightly reminiscent of Oliver Stone’s Wall Street, and the projections on the backdrop alternate between footage of modern-enough people walking and still images of dry landscapes; there are no iPhones, but there is a typewriter. Somehow the overall effect remains that of a Greek tragedy. (The closing song is “Heroin,” by Lou Reed, which also fits: “I wish that I was born a thousand years ago, / I wish that I’d sailed the darkened seas.”) Certain translation choices push the reading of the production as a modern political fable further: Creon uses the Bushism “evildoers” and says that “you need top-notch advisers” to run a government.

Van Hove has made it especially easy to pick up on the similarities between Antigone and Creon: they are both called single-minded and rigid by those around them; at the end of the play, he lies down in the spot where she died. In this light — even if it is a passing illumination — we may ask how it is that Creon is the villain and Antigone the hero. But Creon has all the power, and Antigone has none. Antigone is not a monarch whose personal law becomes everyone’s law; this is why she moves the people of Thebes, while Creon can only frighten them.

Creon’s power is limited, finally, by death. “Death needs to have death’s laws obeyed,” Antigone shouts at him, and her words later take on a prophetic tone, as she causes him more trouble dead than alive. At one point, Binoche appears onstage after Antigone has hanged herself — a bit of unusual but potent stagecraft. The dead multiply: there’s Polynices and Eteocles; Antigone’s betrothed, Haemon, the son of Creon, who kills himself to be with her; and Creon’s wife, who kills herself for the loss of her son. Even Antigone’s sister, Ismene, wants to join in: “Please, sister, do not exclude me from the right / to die with you and share our brother’s requiem.” At the end of the play, Creon weeps, crying out, “Take Creon away / he no more exists than someone who does not exist.” These are characters for whom what is past — Antigone’s incestuous origins, Creon’s tainted ascent to the throne — is prophecy; the future is there waiting for them all along, and the future is death. That the dead are still alive and trying to destroy us is, of course, also the premise of Rogue Nation.

One of the most disturbing moments in Sophocles’ drama stands out especially in the BAM production: Antigone says, of her actions, “People ask / would I have done it for a husband or a child / my answer is no I would not.” A husband or a child can be replaced, she says, but who can give her another brother? One way to read this odd moment is that Antigone has romantic feelings for her brother; the memory of incest haunts this family still. But another reading is that she has been overcome by grief and has lost her grip on reason. Rationality in general is cherished by the characters — Creon, the chorus, Antigone’s sister — but it also proves false or ineffective. Creon says that loyalty to state at all costs is rational, but later he insists that loyalty to family is more important. In both Antigone and Rogue Nation, reason seems useful mainly for cover-ups and self-justifications.

I said that Sophocles’ Antigone is the oldest story of extralegal heroism that I could think of, but there’s another one, only slightly less old, and also quite famous: the story told in the Gospels. I took a friend to see the play at BAM, and as we left the theater he said, “I couldn’t stop thinking of John Boehner.” It was September 25. The pope had addressed Congress the day before, and Boehner had cried as he stood behind him. Shortly before the performance at BAM began, Boehner, a Catholic, announced his resignation as Speaker of the House. My friend went on: “It was like the pope, the ultimate authority, came and said, ‘What you’ve been doing is wrong!’ And Boehner said, ‘I know, I know, I can’t do it anymore!’ ” We both knew that this read on current political events was a fantasy, that Boehner’s resignation almost certainly had more to do with pressure from the extreme right wing of the Republican Party than with the pope’s visit. Still, it was a much nicer story, a more hopeful one, and we were tempted to believe it — it’s an easier beat to follow.