When Marnie Was There (2014), an animated feature by the Japanese director Hiromasa Yonebayashi, tells the story of a twelve-year-old girl who befriends the ghost of her grandmother, Marnie, at the same age. It is typical of recent anime films that the protagonist’s encounter with the supernatural is finally less challenging than the revelation that her foster parents receive government checks for taking care of her. Unlike American animated films, which only gesture at moral seriousness, Marnie and other films like it are centrally, sincerely concerned with the complex trials of adolescence. The casual porousness between the real and the fantastic that makes these films so persuasive and strange is also strangely beside the point.

Marnie was reportedly the last feature to come out of Studio Ghibli, the sandbox of Hayao Miyazaki, Japan’s best-known anime director, who won an Oscar for Spirited Away (2001). Among Miyazaki’s spiritual successors, perhaps the finest is a non-Ghibli director, Mamoru Hosoda. His films might be described as YA, though the term belies the confidence of Hosoda and his longtime collaborator, the screenwriter Satoko Okudera, in both the maturity of young viewers and the openness of their elders to childish things. Compare this balance — present, too, in Ghibli — with the Disney–Pixar dichotomy of kablooie for kids and over-their-heads jokes for parents: “Foot size doesn’t matter”; “I thought the earth wasn’t supposed to move until the honeymoon”; “There are no bears in San Francisco.”

In Hosoda’s The Girl Who Leapt Through Time (2006), a seventeen-year-old tomboy acquires the ability to make small backward skips in time, which she uses mostly to ace pop quizzes, drag out karaoke sessions, and forestall the dissolution of her comfortable platonic triad with two male classmates. Her leaps are finite, and in dodging the overtures of one of the boys she uses them up before she learns that he is from the future and that her spendthrift ways have trapped him in the present. In Summer Wars (2009), a gawky eleventh grader and part-time coder named Kenji gets roped into posing as the fiancé of a popular senior at her great-grandmother’s ninetieth birthday. Amid the festivities at the family’s ancestral estate, a malicious computer program called Love Machine hijacks a capacious online world called Oz and compromises the security of the real world’s global infrastructure. Hapless Kenji and his hosts must try to return Oz to order and stop Love Machine from crashing a satellite into a nuclear plant. The film presents, in Kenji, the credible growing of a pair.

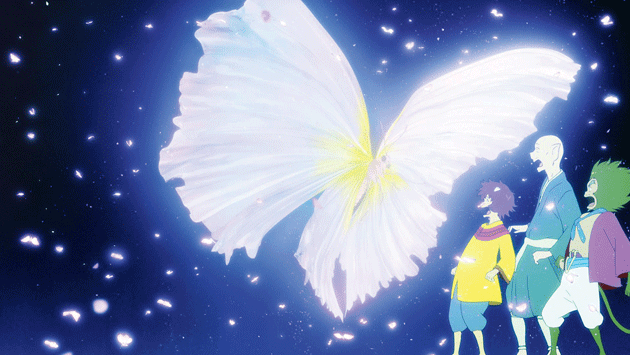

Wolf Children (2012) contains Hosoda’s most striking use of a fantastical premise toward mundane ends. A self-supporting college student falls in love with a deliveryman who moonlights as a wolf. After he abruptly dies, she quits school to raise their two shape-shifting offspring; all three flee to the countryside when social services starts prying into the children’s vaccination status. As the daughter, Yuki, reaches puberty, she decides to be human full-time. Her younger brother, Ame, who has begun exploring the forest under the tutelage of an old fox, resolves to be fully lupine and succeed his sensei as guardian of the mountain. “You’re barely ten years old,” his mother responds. “A ten-year-old wolf is an adult, but that’s different. You’re not a —” She stops, for the first time awed by the change in her son.

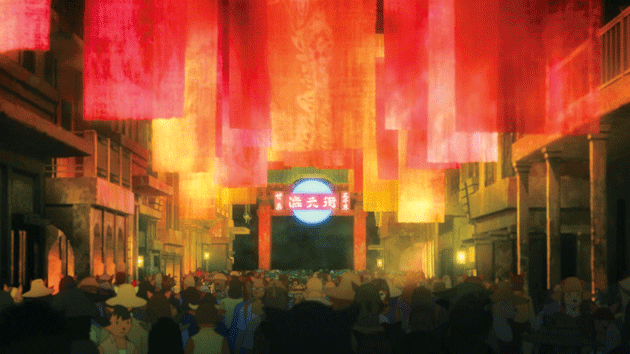

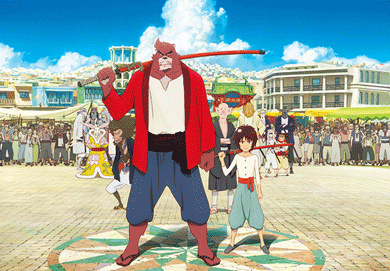

Hosoda’s latest film, out soon in the United States, is called THE BOY AND THE BEAST. The boy is Ren, a nine-year-old who runs away from his guardians and takes up an invitation to apprentice himself to Kumatetsu, a talented but loutish man-bear. (In the Japanese title the word for “beast” is bakemono, a genus of shape-shifting animal spirit.) Kumatetsu, a childless martial artist and part-time menial laborer, is the dark horse for the rulership of Jutengai, a thriving town in a parallel beast universe. Most assume that the gladiatorally determined title will go to Iozen, an upstanding family man-boar. But to make things interesting, Kumatetsu’s unorthodox choice of a human apprentice is approved by the outgoing lord, a sort of Taoist-immortal rabbit with flowing mustaches who contemplatively brandishes carrots, wears superb Song Dynasty–style robes with floral and fructal motifs, and radiates the disarming battiness of self-transcendence. Eight years pass in training. Kumatetsu and Iozen ready for battle.

With its martial-arts story line, its high-stakes fights and showy climactic sequences, and its emulation of camera movements, The Boy and the Beast might appear more conventional than Hosoda’s previous films. But several factors complicate this view. One is the gorgeous, disorienting art direction. Tokyo is rendered as a dreary watercolor of neon signage, while Jutengai appears to be a medieval Italian stone town with hurricane fencing and miniskirts. The look of Hosoda’s characters is more modern and jagged than Ghibli’s, but the landscapes, like those in many of the studio’s films, retain a hand-colored prewar-woodblock quality, and they fill out the wide-screen frame like an animated Lawrence of Arabia. There are flagstone paths lined with luminarias that lead through cycad forests, constellations that helpfully connect their own dots in the twilight sky, and unanthropomorphic roosters and deer that stare with creepy pitless eyes.

The family dynamics in The Boy and the Beast are more astute and involved than they are in any of Hosoda’s other features. At the age of seventeen, Ren begins revisiting the real world — back to the rainy, claustrophobic, blue-washed evenings of Tokyo — and tracks down his long-absent father, a well-meaning salaryman-milquetoast. Ren goes to the library and meets a girl named Kaede. With her help, he starts making his way through Moby Dick and A Thousand Barrels a Second and catching up on years of missed coursework.

Back in Jutengai, Kumatetsu confronts Ren about his absences. “I found it under your mattress,” he says, tossing a math textbook on the table. “I want to go to human school,” Ren says. “I found my dad. I’ll go live with him.” Kumatetsu, who took seriously his responsibilities in loco parentis, throws a tantrum. At the same time, Iozen’s elder son, Ichirohiko — himself a human adoptee — wonders why he hasn’t grown tusks or a snout like his father’s. Ichirohiko’s crisis drives him to violence, which eventually leads to a spectral betusked sperm whale chasing Ren and Kaede through the streets of Tokyo and Kumatetsu reincarnating himself as a flaming sword to fill a visible hole of metaphysical darkness in Ren’s chest. Then Ren goes to college.

In Hosoda’s Summer Wars, the cartoonish sterility of Oz borrows heavily from the iconography of Takashi Murakami, the visual artist with whom Hosoda collaborated on Superflat Monogram (2003), an animated short made for Louis Vuitton about a girl who falls through the digital looking glass. In both films, the white void of the digiscape is dotted with buoyant, cheerful beings that are familiar from Murakami’s paintings. The contrast in Summer Wars between Oz and the early-seventeenth-century manse of Kenji’s faux fiancée mirrors that between Murakami’s bright pop creations and the majestic spaces such as Grand Central Terminal and Versailles where they have been installed. Such a tension between the antique and the modern suffuses Murakami’s work itself, and is reflected in his term “superflat.” The concept refers both to the lack of one-point perspective in traditional Japanese painting and to Murakami’s clever repurposing of this quality in his own painting. But superflat also describes the deracinated, globalized imagery he deploys.

The figures of Murakami’s menagerie recur in his work across mediums and genres, including his debut feature, a live-action film called JELLYFISH EYES that came out on DVD last month. A sixth grader named Masashi has just been resettled, along with his mother, from a radiation-contaminated evacuation zone. (His father was killed in a tsunami that was part of the same disaster.) Masashi’s gloom lifts when he discovers a paunchy sprite rummaging in the pantry, whom he christens Kurage-bo (“Jellyfish Boy”). Masashi learns that his new classmates all have similar companions — cute, big-eyed animals that have been summoned into being by handheld devices. These friends are called FRIENDs. The devices that allow children to conjure them are distributed by a quartet of sinister black-cloaked dorks who run a top-secret lab in which they harvest, via the devices, the powerful negative energy of sixth graders. There is plenty to go around, because everyone’s parents are dead or abusive or in a cult. The black-cloaked four plan to use this energy to save the world (FRIEND: “life-Form Resonance Inner Energy Negative emotion Disaster prevention”), which, naturally, will require them first to destroy it, by calling forth the ultimate FRIEND: a bulbous, many-eyed Godzilla creature named Oval.

Murakami has called himself a B-movie director, and with Jellyfish Eyes, which is soon to have a sequel, this feels especially true: the film is cheesy, depthless, and superflat. (Reverential screenings of the film at American museums before its cinematic release brought Murakami’s joke — that any anxiety about delineating “real” from popular art is flattened in Japan — full circle.) Jellyfish Eyes, like all of Murakami’s work, draws heavily on anime and manga, and it owes much to the Pokémon and Digimon franchises, with their adorable monsters in staged combat, and also to the adolescent-centric apocalyptic setting of the Neon Genesis Evangelion anime features.

Like Evangelion, the Godzilla films, Summer Wars, and so many other apocalyptically tinged Japanese narratives, Jellyfish Eyes shows a profound preoccupation with Japan’s atomic traumas — Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and now Fukushima. The ordeal of the Pacific War’s denouement and the U.S. occupation that followed it, Murakami has argued, led to nothing less than a national psychic infantilism: “Our society and hierarchies were dismantled. We were forced into a system that does not produce ‘adults.’ ” This, he claims, is partly responsible for the rise of kawaii (“cute”) — Hello Kitty livery on passenger jets, Lolita costumes on grown women — and the culture of otaku, that is, nerds whose obsessive niche interests have spilled into the mainstream over the past three decades. At the end of Jellyfish Eyes, Masashi and his classmates avert catastrophe by sacrificing their kawaii companions to defeat Oval. But it so happens that the creatures can be harmlessly resurrected by the class otaku using a hacked device. The kids, forfeiting nothing, are frozen in childhood with their unimaginary FRIENDs. “A blast of pure white light, a summer eternally seared,” Murakami has written. “My own consolation, a still endless summer vacation.”

Oval, in other incarnations, has two bubble-headed “acolytes” named Kaikai and Kiki. Kaikai Kiki is the name of the studio in which Murakami’s own acolytes help realize his massive projects. And kiki kaikai is a Japanese term for the uncanny atmosphere created “whenever ghouls or spirits appear.” This captures perfectly the unsettling feeling of watching Chiho Aoshima’s TAKAAMANOHARA (“The Plain of High Heaven”), an ambitious seven-minute video projection, created in collaboration with the New Zealand animator Bruce Ferguson, that premiered last year at the Seattle Asian Art Museum. At Kaikai Kiki, Aoshima oversaw the digital vector tracings that are endlessly duplicated to manifest recurring elements in Murakami’s paintings. She previously worked in advertising and has no formal fine-art background; Adobe Illustrator remains the essential medium of many of her drawings, dozens of figures from which have been recombined in Takaamanohara.

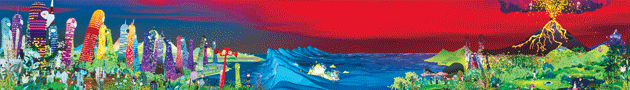

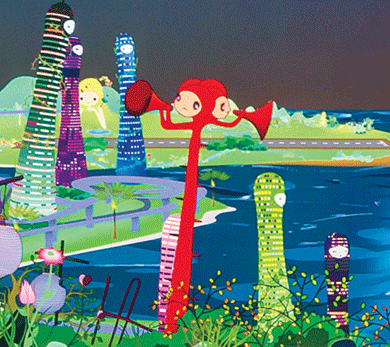

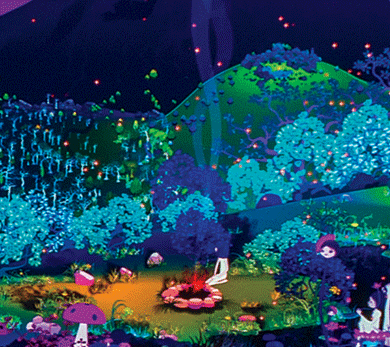

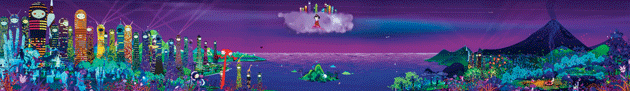

Installation views (details) from Takaamanohara, 2015, an animated mural and 3-D soundscape by Chiho Aoshima © The artist/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd. Photographs by Joshua White

The looped projection, some sixty feet wide, is a static shot of a fanciful landscape. On the left and right is land, and in the middle is a sea with a few small islands. The hills and mountains on the left all have placid human faces, as do the swaying, wormlike skyscrapers. The land on the right is wilder, its mountains are faceless, and its lotus ponds and forests are populated with sprites, dryads, and other, unplaceable fairies. Every being in this world is female.

The many-colored buildings grow out of the ground like mushrooms. A goddess wearing a green kimono floats in, accompanied by cloud-ghosts, and darkness falls. A few buildings sprout on a cloud in the sky and also on the right side, where the tallest mountain, a volcano, erupts; this may be the flatulence of a nymph who has climbed into the vent. A tsunami sweeps buildings from the city into an ocean whirlpool. Flying nymphs spawned by the volcano nymph rain lightning on nearby buildings that burn and collapse. A hunchbacked pollution deity crawls out of the ruins of the burned buildings and shuffles her way into the sea. A rainbow arcs over the world in benediction. As the deity disappears into the water, new buildings sprout again.

The many-colored buildings grow out of the ground like mushrooms. A goddess wearing a green kimono floats in, accompanied by cloud-ghosts, and darkness falls. A few buildings sprout on a cloud in the sky and also on the right side, where the tallest mountain, a volcano, erupts; this may be the flatulence of a nymph who has climbed into the vent. A tsunami sweeps buildings from the city into an ocean whirlpool. Flying nymphs spawned by the volcano nymph rain lightning on nearby buildings that burn and collapse. A hunchbacked pollution deity crawls out of the ruins of the burned buildings and shuffles her way into the sea. A rainbow arcs over the world in benediction. As the deity disappears into the water, new buildings sprout again.

I must have watched Aoshima’s loop half a dozen times before I found the seam. The enormous, generous two-dimensional landscape floods and ebbs with life and color; its myriad changes are never subordinate to what pass for the principal narratives. Tiny flying saucers suck up a giraffe and a ship and a tree, then go back to outer space. Off to the right, fairies dance on toadstools; at night a sort of laser-light show emanates from the buildings. Planes make use of a runway behind the city, auto traffic runs on overpasses, bugs drowse through the air. Temporary windows into the sea reveal a school of fish tended by a mermaid. A canopy of chattering skulls sprouts from one nymph’s head and quickly vanishes. An elf-woman the size of a building wanders in mod clothing among the buildings. Cherry blossoms proliferate, then disperse on the breeze. A nymph who is also a rock promontory buries her head behind her arm beside the sea. The soundscape murmurs and tinkles and shrieks. The sky cycles orange, fuchsia, red, and blue.

I must have watched Aoshima’s loop half a dozen times before I found the seam. The enormous, generous two-dimensional landscape floods and ebbs with life and color; its myriad changes are never subordinate to what pass for the principal narratives. Tiny flying saucers suck up a giraffe and a ship and a tree, then go back to outer space. Off to the right, fairies dance on toadstools; at night a sort of laser-light show emanates from the buildings. Planes make use of a runway behind the city, auto traffic runs on overpasses, bugs drowse through the air. Temporary windows into the sea reveal a school of fish tended by a mermaid. A canopy of chattering skulls sprouts from one nymph’s head and quickly vanishes. An elf-woman the size of a building wanders in mod clothing among the buildings. Cherry blossoms proliferate, then disperse on the breeze. A nymph who is also a rock promontory buries her head behind her arm beside the sea. The soundscape murmurs and tinkles and shrieks. The sky cycles orange, fuchsia, red, and blue.

It is often said, as it is of Murakami, that Aoshima takes “inspiration” from anime and manga, though she denies this. She admits affinity with classical ukiyo-e art, and her prints of rope-bondage scenes and Boschian hellscapes recall certain sadistic nineteenth-century woodblocks as much as they evoke contemporary Japanese animated pornography. Aoshima’s imagery appears profuse with conventional kawaii, but Murakami himself, who throughout the 1990s revised his ambiguous characters to a state of universal cuteness, may offer the distinction that defines her style. “The notion of kawaii is extremely positive,” he has said. “It expresses the luminous side of an enchanted world. The ghosts, as divinities, are fairly close to its dark side.”

Aoshima’s kawaii somehow encompasses the latter category as well. Her figures are variously hebephiliac or cuddly, and are often, also, undead. This is but one meeting point of reality and unreality in the dark and luminous world of Takaamanohara, and part of a broader ambiguity: what is alive or not-alive, what is organic or inorganic, which ghosts are digital (like Love Machine and the FRIENDs) and which astral (like Kumatetsu and Marnie). It is impossible to identify a true seam in Takaamanohara because everything is always becoming something else. The dancing dead return to the grave. Fairies turned demonic return to pink innocence. Doe-eyed buildings regenerate endlessly from the earth. Aoshima’s vision is not elegiac, not an eco-cautionary Miyazakian tale, not about a single anxious future. There is no beginning or end to her apocalypse. She has superflattened the future and the past. She is the girl who leapt through time.

Aoshima’s kawaii somehow encompasses the latter category as well. Her figures are variously hebephiliac or cuddly, and are often, also, undead. This is but one meeting point of reality and unreality in the dark and luminous world of Takaamanohara, and part of a broader ambiguity: what is alive or not-alive, what is organic or inorganic, which ghosts are digital (like Love Machine and the FRIENDs) and which astral (like Kumatetsu and Marnie). It is impossible to identify a true seam in Takaamanohara because everything is always becoming something else. The dancing dead return to the grave. Fairies turned demonic return to pink innocence. Doe-eyed buildings regenerate endlessly from the earth. Aoshima’s vision is not elegiac, not an eco-cautionary Miyazakian tale, not about a single anxious future. There is no beginning or end to her apocalypse. She has superflattened the future and the past. She is the girl who leapt through time.

At the end of the occupation of Japan, General Douglas MacArthur proclaimed that the “Japanese . . . in spite of their antiquity measured by time, were in a very tuitionary condition. Measured by the standards of modern civilization, they would be like a boy of twelve.” The nation took umbrage, but Japanese artists do seem particularly aware that we are always and forever only growing up — and what a magnificent disaster it is.