Discussed in this essay:

Letters to Véra, by Vladimir Nabokov. Edited and translated by Olga Voronina and Brian Boyd. Knopf. 864 pages. $40.

Writers produce marital advice of varying emotional fitness and reliability. Hemingway pushed the hunter virtues of ruthlessness and traveling light: “The first great gift for a man is to be healthy and the second, maybe greater, is to fall [in] with healthy women. You can always trade one healthy woman in on another. But start with a sick woman and see where you get.” John Updike, chasing the topic across a library shelf, became a spokesman for dissatisfaction. “A person who has what he wants,” he told The Paris Review, “a satisfied person, a content person, ceases to be a person.” Happiness erases self, powers down the receptors; the “eyes get fat.” Lorrie Moore took over Updike’s consulting room as prose relationship specialist. She noted where Updike had directed the credit (“Perhaps I could have made a go of the literary business without my first wife . . . but I cannot imagine how”) and shared advice in her sly style: light to your face, a comic thump as your back turns. “Women writers should marry somebody who thinks writing is cute. Because if they really realized what writing was, they would run a mile.” Later on she reflagged: “Writers all need Véra.”

Véra and Vladimir Nabokov, Gstaad, Switzerland, 1971, by Horst Tappe © Horst Tappe Foundation/Granger, New York City

“No marriage of a major twentieth-century writer lasted longer,” Brian Boyd tells us at the start of Letters to Véra, which collects Vladimir Nabokov’s letters to his wife of fifty-two years. Companion, agent, live-in editor, bodyguard, and the dedicatee of almost all her husband’s books, Véra Nabokov, née Slonim, has reached a strange elevation in our cultural sky. “The Legend of Véra Nabokov,” runs the headline in a recent Atlantic article: “Why Writers Pine for a Do-It-All Spouse.” It’s easy to understand the pining. When Vladimir crossed campus to teach, Véra walked a few steps ahead, opening doors. She did all the driving. Also the paper grading, letter replying, contract haggling, editor nudging. She carried a pistol, for Vladimir-protection on the more hazardous butterfly-collecting trips. (He liked to have her unbag and exhibit the gun at parties.) She was his first and best reader, greeting the books when they were still, as her husband said, “warm and wet.” She prevented him from burning Lolita. In 1981, four years after the writer’s death, Martin Amis made a pilgrimage to the Swiss hotel suite that was part of the Nabokovs’ Lolita winnings. An awful moment: Véra misconstrued a compliment to Vladimir as criticism. “What?” she asked. “And,” Amis writes, “every atom in her body seemed to tremble with indignation.”

Cracking open Letters — with its slightly repellent cover photo, the young couple overdressed in a way that seals them into the past — we expect something impossible: the swoony and romantic bolted to the solid how-to and D.I.Y. The first thing you notice is Nabokov’s endearments — in the leadoff letter he is already calling Véra “my strange joy, my tender night.” The endearments pile up, crossing borders, oceans, decades. These are more or less in order:

My lovely, my sun, my song, my enchantment, my kitty, my mousie, my sweet little legs, my long, warm happiness, my grand ciel rose, my multi-colored love, my gold-voiced angel, my radiance, my life.

You understand the crucial word. Always the “my.” “I need so little,” he wrote at the beginning. “A bottle of ink, a speck of sun on the floor — and you.” What mattered was binding Véra, keeping her there by this fond possessive.

The couple met in 1923, at a springtime Berlin charity ball. Nabokov might have appreciated the double patterning: the greatest generosity — his life’s partner — went to him; and they would be broke for three decades. Véra arrived masked. She had the kind of in-person loveliness that comes wrong with photos. (Years later she told a friend, in the Nabokov style that puts even inanimate relations on a squalling and personal footing: “The camera and I have been at odds since I was a child.”) They talked on a bridge overlooking a canal.

In the letter he sent after, what comes through most is gratified, mistrustful surprise. They had spoken with such instant harmony that he suspected a trick. “I won’t hide it,” Nabokov wrote. “I’m so unused to being — well, understood.” It’s the first entry in Letters to Véra, and really the whole thing: a voice finding a listener, and a fellow speaker. She was the person, he said, with whom he could talk about thoughts and clouds. “Yes, I need you, my fairy-tale,” he wrote. And a few months later: “With you one needs to talk wonderfully.” And a few months after that: “As if in your soul there’s a place prepared in advance for my every thought.”

Both were born in St. Petersburg — he in 1899, she in 1902 — and both were de-citizened by revolution in 1917. Before their marriage in 1925, Vladimir, following a tradition among Russian litterateurs, handed over an intercourse résumé. Here’s everybody. It contained twenty-eight names. Véra’s precursor was Svetlana Siewert, a seventeen-year-old émigré; she and Vladimir were briefly engaged until her parents decided that they didn’t like the look of his financial prospects. For he was already, unavoidably, a writer. If he’d lost both hands, the young Vladimir claimed, he’d learn to write with his teeth. “I am becoming more and more firmly convinced,” he told Véra early on, “that art is the only thing that matters in life. I am ready to endure Chinese torture to find a single epithet.” (This echoes an odiferous pain-for-gain ratio proposed by Flaubert in a letter of his own: “There is a Latin phrase [applied to misers] that means roughly, ‘To pick up a farthing from the shit with your teeth.’ I am like them: I will stop at nothing to find gold.”) Véra, who memorized and translated poetry, was Vladimir’s immediate accomplice. A spouse less committed to art would have required him to be less committed.

Letters to Véra is a one-sided affair. We get only Vladimir’s outgoing; Véra destroyed her replies. She was, in any case, an infrequent correspondent, a fact that pained her husband; the Germany years of the book (400 pages) could be retitled “Unreturned Letters to Véra.” They provide a warm and appealing portrait of the young artist. Nabokov wrote fiction into the small hours, rose late, and earned a shaky living tutoring the children of the Berlin rich in a triumvirate of subjects: tennis, boxing, poetry. (Aspects of the Nabokov style: elegance, violence, eloquence.) He told Véra everything (his favorite snacks, his new clothes), sent her sketches of mornings (“a boiled-milk sky, with skin — but if you pushed it aside with a teaspoon, the sun was really nice”) and twilights (“Wonderful pink feathers of parallel clouds . . . the ethereal ribs of heaven”). When he does receive a return letter, his gratitude is matchless, palpable: “Your letters . . . they’re almost touches, and that is the greatest thing you can say about a letter.” And: “I keep walking around in the letter you wrote on, on every side, I wander over it like a fly, with my head down, my love!” The letters even give instruction in how to fight: “I am furious with you, but I love you very dearly.”

The Nabokovs’ only child, Dmitri, was born in May 1934, eleven years after the night on the bridge over the canal. Since Vladimir was home at the time, Letters to Véra skips the delivery. The story resumes two years later, with Vladimir on the road, sending Véra a lovely account of the changed emotional temperature of fatherhood: “When I think about him, there’s a kind of heavenly melting inside my soul.” He was about to begin a series of actions that would nearly demolish the family he and Véra had made.

In those eleven years Vladimir had become famous. His first novel, Mary (1926), served its readership as a mirror: the émigré life of shabby rooms, frayed wardrobe, bright nostalgia. When a review came in soft, Vladimir wrote Véra, offering a perfect writer’s umbrella: “Blaming a critic is like blaming the rain.” The Luzhin Defense (1929), about a mentally unsound chess genius, made his name: it’s the sort of book that nicks the palms of other writers like a razor. “This kid has snatched a gun,” émigré Ivan Bunin, who’d later win the Nobel Prize for Literature, said, “and done away with the whole older generation, myself included.”

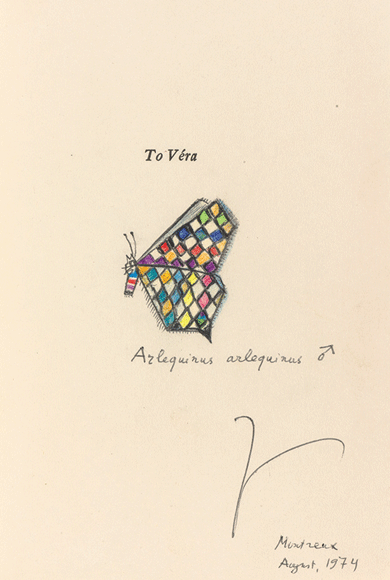

Right: A copy of Nabokov’s Look at the Harlequins! inscribed by the author to his wife, 1974 © The estate of Vladimir Nabokov, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC. Courtesy Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

A trio of Nabokov’s Berlin-era books play a trick that Quentin Tarantino and the Coen brothers would perfect in our time: take a genre, race the engine, you’ve got a vehicle to develop and demonstrate your talent. King, Queen, Knave (1928) and Laughter in the Dark (1932) are both marriage noirs. In the former, the wife cheats; in the second, it’s the husband. (Laughter is a nasty, perfect weekend book, though King contains Nabokov’s best double entendre. Unhappy wife discussing husband’s financial vigor: “His business is enormous — I mean, my husband’s firm.”) Despair (1934) is an inverted mystery: we meet murderer and victim early on, then wait all novel for the crime. When the book was published, the glow was visible even in far-off, peaceful America. In 1935, Vladimir wrote his mother about the busted relationship between esteem and wallet. “The New York Times says ‘our age has been enriched by the appearance of a great writer,’ ” he explained, “but I have no good trousers.”

So he’d gone on tour — paid readings, lunches, meet-and-greets. From Paris, the publishing capital of the emigration, he sent home a complaint that’s being repeated right this second at a Brooklyn party or M.F.A. table. “There are too many literary men here. I’ve had my fill.” He was a confident auditorium tamer: “The audience was good, simply wonderful. Such a big, sweet, receptive, pulsing animal, grunting and chuckling in the places I needed, and then obediently dying down again.”

It’s around now that the tone of the letters shifts. This may be the progression of any marriage: possibility to responsibility, breathless romance finding its standing pulse. Vladimir and Véra have become joint proprietors of an artisanal shop selling one exquisite item. These, then, are “Business Letters to Véra” — updates to the home office from a salesman on the road. In place of romance, we find requests for addresses, manuscripts, counsel. “I’m carrying out your little instructions.” “Have you sent Despair yet?” “I could have left the blue jacket behind.” “I am very sorry to pile postal duties on to you.” “Don’t forget all my requests.”

From the beginning, he’d grasped one condition of their fragile luck. “In everything enchanted there’s an element of trust,” he wrote. Spoil the trust, break the enchantment. In 1936, on business in Paris, he met the blond, invigorating divorcée Irina Guadanini. The moment could not have been worse. As a Jew in Hitler’s Berlin, Véra was no longer permitted to work. It was time to go. (A friend — the future Orthodox archbishop of San Francisco — saw Véra arranging her departure. She explained that the city was no longer safe for Jews. The future archbishop suggested they ought to “stay and suffer.”) Meanwhile, Vladimir was writing to Irina about their perfect affinity, assuring her that he was prepared to leave his wife: “I love you more than anything on earth.”

The letters home turn evasive. It is heartening to learn: a genius lies no better than anyone else. “There’s no power in the world that could take away or spoil even an inch of this endless love,” he wrote Véra. “And if I miss a letter for a day it’s only because I absolutely can’t cope with the crookedness and twists of time I’m living in now. I love you.” After she learned the truth, Véra offered him the chance to leave. The simplest of his endearments to her was “my life.” Given the choice, Nabokov returned to his life. Irina never remarried. She kept a scrapbook of Nabokov’s successes (it included photos of Véra) and died poor at a home for aged Russians outside Paris in 1976.

Many successful relationships include a casualty, another person (a set of expectations and a potential future) left stranded on the platform. The Nabokovs relocated to Paris, where Vladimir composed his first novel in English, The Real Life of Sebastian Knight (1941). The family occupied a small apartment — Nabokov wrote in the bathroom, throwing a suitcase over the bidet to make a desk. (A real-life staging of the Flaubert ideal.) It’s an apology book. Sebastian Knight, the Nabokov-like writer-hero, inexplicably leaves the Véra-like Clare Bishop for another woman — and dies. “Girls of her type do not smash a man’s life,” the book explains. “They build it.” Even in the thick of the affair with Irina, Vladimir had written his wife: “Without the air which comes from you I can neither think nor write — I can’t do anything.” They left on a boat for America in May 1940, two weeks ahead of the Germans.

In the United States, the wound of the Irina affair slowly closed. The couple were rarely separated — “American Letters to Véra” takes up sixty pages — and when they were, Vladimir wrote that he was not near women, or that the women he was near weren’t pretty. (“The girls are all sporty-looking . . . lots of pimples” is him characterizing the Wellesley College student body.) In 1942, five years post-infidelity, he sent Véra an oddly formal sentiment: “I think about our life together with great pleasure — I hope it will continue for years.”

Most of the letters Nabokov wrote during this period were addressed to Edmund Wilson, The New Yorker’s literary critic, who helped smooth the Russian’s professional transition to America. Wilson became a kind of correspondence wife: the person to whom Nabokov sent irritations and excitements. With Wilson’s introduction, he began selling his past, piece by piece, to The New Yorker — the extraordinarily wealthy childhood (the teenage Nabokov inherited an estate worth millions of dollars); the vanished, tinkling world of Russian tutors and governesses; the flight from the Bolsheviks; the years with Véra.

The present continued non-wealthy, and Vladimir took teaching jobs, accumulating an impressive set of stickers for the car window: Stanford, Wellesley, Cornell. (Nabokov to Wilson: “I am sick of teaching, I am sick of teaching, I am sick of teaching.”) Summers, the Nabokovs would traverse the country’s interior in search of butterflies. In 1951, he wrote Wilson about Telluride, Colorado:

Awful roads, but then — endless charm, an old-fashioned, absolutely touristless mining town full of most helpful, charming people — and when you hike from there . . . with the town and its tin roofs and self-conscious poplars lying toylike at the flat bottom of a cul-de-sac valley . . . all you hear are the voices of children playing in the streets.

Within a few years, this dispatch would be reworked into the passage that ends Lolita (1955):

I grew aware of a melodious unity of sounds rising like vapor from a small mining town that lay at my feet, in a fold of the valley. . . . Soon I realized that all these sounds were of one nature. . . . What I heard was but the melody of children at play. . . . And then I knew that the hopelessly poignant thing was not Lolita’s absence from my side, but the absence of her voice from that concord.

“Only ambitious nonentities and hearty mediocrities exhibit their rough drafts” was Nabokov’s prickly answer to an interviewer who’d offered to inspect some of his. “It is like passing around samples of one’s sputum.” We get to see how Proust shaped his novel, the pasted-in third and fourth thoughts dribbling out of the fat manuscript; how Hemingway drilled his sentences down to a lean, ideal Hemingway-ness. Nabokov boxed away his drafts. Letters to Véra opens the workshop door and shows us Vladimir not in his accredited hard-shell case of genius but as a soft, vulnerable practicing writer.

Throughout Letters we keep spotting photos of passages whose grown-up selves we’ve met and underlined in the books. “You came into my life — not as one comes to visit,” Vladimir wrote Véra of their lightning courtship. “You know, ‘not taking one’s hat off.’ ” Two decades later, he compressed the metaphor for one of the nicest sentences in The Real Life of Sebastian Knight: “She entered his life without knocking.” A quick tourist’s snapshot of Paris — “On the Arc de Triomphe, a fragment of the frieze suddenly comes to life — a pigeon taking off” — wheels back for capture in the same novel: “It seemed as if bits of the carved entablature were turned into flaky life. . . . ‘stone melting into wing.’ ”

Again and again, we see what Charles Kinbote, in Pale Fire (1962), calls the magic of a mind “perceiving and transforming the world, taking it in and taking it apart, re-combining its elements.” An early promise to Véra — “Most of all I want you to be happy and it seems to me that I could give you that happiness. . . . I am ready to give you all of my blood” — gets enhanced and repurposed as an aching declaration in Pnin (1957): “I am not handsome, I am not interesting, I am not talented. I am not even rich. But . . . I offer you everything I have, to the last blood corpuscle, to the last tear. . . . I may not achieve happiness, but I know I shall do everything to make you happy.” A tossed-off glimmer from 1941 — “I love you, my darling, I’m kissing your little liver” — gets expanded into a startling romantic-anatomical wish in his most famous book: “My only grudge against nature was that I could not turn my Lolita inside out and apply voracious lips to her young matrix, her unknown heart, her nacreous liver, the sea-grapes of her lungs, her comely twin kidneys.” The idea is so enticing that it found a second home in Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections: “In the orange light of his shame he felt as if he were abusing her internal organs. He felt like a surgeon atrociously fondling her youthful lungs, defiling her kidneys, sticking his finger in her perfect, tender pancreas.”

Nabokov can sometimes recede in our bookstore imagination — and we’ll think of him as finicky, cold, hyperaestheticized. As that last passage reminds us, he is the best writer on the physical — on the temporary pleasures of our habitation in a body — that we have. It’s even how he approached reading: disregard everything, he advised his Cornell students, but “the tingle in the spine.” On the spinal highlight of sex, of course, he remains unsurpassed. He maintained that Lolita was not a prurient book — this was on a strict, letter-of-the-law basis: no dirty words — but the novel is dizzyingly sensual, as in this morning-after image of Humbert: “Every nerve in me was still anointed and ringed with the feel of her body.” Ada (1969) presents a willowy and somehow autumnal vision of fellatio: “That first time she had bent over him and he had possessed her hair.” Martin Amis compared this strain of Nabokov to “a recreational drug more powerful than any yet discovered or devised.” In the manner of a drug, Nabokov accelerates perception and appreciation. He can even eroticize the breakfast nook: “The classical beauty of clover honey . . . freely flowing from the spoon and soaking my love’s bread and butter in liquid brass.”

This reader fell in love with Nabokov via a half-sentence in Pale Fire. The hero takes a sleepy, eye-watering yawn — and the world “shivered and dissolved in the prism of his tears.” It is shockingly intimate: snapshots by a genius of the junk moments the brain doesn’t bother to file. Nabokov’s people are constantly yawn scrunching, nose wiping, bug-bite scratching. Just before the heroine of the story “Spring in Fialta” expires in a car accident, we watch her “for the last time in her life . . . eating the shellfish of which she was so fond.” This is it exactly: the things our bodies require, while our thoughts seek drier gratifications. In Nabokov, the body isn’t intrusive. It reminds you of its needs in a gentle way, like a pet nudging your calf: to be watered, fed, drained, entertained. This is the central joke in Lolita — an intelligent man dragging himself toward an adolescent across mud and thorns — and I think what Nabokov meant when he said that the novel’s first throb came from a newspaper story about a zoo ape trained by scientists to draw: “This sketch showed the bars of the poor creature’s cage.” The bars are our fragile, hungry, satisfying bodies.

Lolita’s success — “Hurricane Lolita,” he calls it in Pale Fire — was mammoth and immediate. And when it arrived, in 1958, Vladimir was measured. The small business that he and Véra had operated for so long had gone multinational. “All this ought to have happened thirty years ago,” he wrote his sister. There were Lolita dolls, Lolita cartoons (arriving Martian: “Take me to your Lolita”), a Kubrick movie, a San Francisco drive-in serving Lolitaburgers. The book was offered in prison to the Nazi leader Adolf Eichmann, who returned it with a frown. Again, Nabokov would have appreciated the patterning: an imprisoned criminal from the regime that had menaced his wife and son (and killed his brother Sergey, an outspoken critic of the Nazis) found Nabokov’s work “unwholesome.”

In 1960, the enriched Nabokovs recrossed the Atlantic and soon took up residence at the Montreux Palace Hotel, in Switzerland. (Nabokov sent Dmitri — who’d become something of a playboy in Italy, where gossip writers dubbed him Lolito — this safe-sex jingle: “For his own good / A wolf must wear a Riding Hood.”) There, they hunkered down for happiness — with results that Updike might have predicted. In these final letters, Vladimir becomes a figure of stuffed and wobbling prosperity, and we get what might be called “Murmurs to Véra.” “At half-past four went out to drink some hot chocolate (wonderful!).” “I bought more oranges.” “They heat the place very well here.” In King, Queen, Knave, one of Nabokov’s characters thinks: “Every instant all this around me laughs, gleams, begs to be looked at, to be loved. The world stands like a dog pleading to be played with.” In 1970, vacationing in Sicily, waiting for Véra’s arrival, an actual dog crosses his path — and that’s all the description we get: “Shaggy dog.” These were the years of what Vladimir, in Ada, his last great novel, called their “dot-dot-dotage.”

We can travel from 1923 to 1970 in eight hours (long flight plus meal) under the reading lamp, or with our sharp-edged tablet poking our thigh. Nabokov made the actual journey, and we know — and he does not — what he’s lost: alertness and attention, the desire to be adored by Véra, which, in these pages, makes him lovable to us. The longtime couple from Ada die, Nabokov writes, into literature — “into the prose of the book or the poetry of its blurb.” Vladimir died in 1977, Véra in 1991. Dmitri became a flame tender, taking over Véra’s former jobs: checking contracts, taste-testing translations, escorting Vladimir into print. He never married, died in 2012, and the demographic episode of the Nabokovs was folded back into history.

Vladimir wrote Véra a year into marriage: “I feel now especially sharply that from that very day when you came to me masked, I’ve been wonderfully happy, it’s been my soul’s golden age.”

Those Hemingway reflections on marriage come from a 1943 letter about F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose story, to Hemingway, was about failed stewardship of talent. In A Moveable Feast, Hemingway committed one of the great acts of writer-on-writer violence. The question was career longevity, how to retain the bright, surprising thing. “His talent was as natural as the pattern that was made by the dust on a butterfly’s wings,” he wrote of his friend. “Later he became conscious of his damaged wings and of their construction and he learned to think and could not fly any more because the love of flight was gone and he could only remember when it had been effortless.”

It’s a surprise: Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and Nabokov — born within four years of one another — were all more or less members of the same entering class. Fitzgerald and Hemingway seem to slip back into their century; Nabokov shrugs off the bonds and styles of his time and steps firmly into ours. Hemingway wrote those sentences at the end of his life, on marriage number four, at a moment of shakiness and depletion. He was so disheveled he had to borrow the butterfly image — from the writer he was condemning. “With the clumsy tools,” Fitzgerald had written in a short story, “he was trying to create the spell that is ethereal and delicate as the dust on a moth’s wing.”

Nabokov’s work feels unified — seems always to be powerfully describing the same internal landscape — because across many nations and decades Véra and he together kept that inner world consistent. It may be what Brian Boyd is getting at: longest marriage, longest career; novels from 1926 to 1974. The prize was a by the same author containing Pale Fire, Ada, Lolita, Pnin. This was the sort of life Véra had moved toward, stepping with Nabokov onto that bridge. Talent may be mysterious; a setting for that talent is maintainable. Nabokov’s work glided across five decades, with the same pattern on its wings. “I am afraid” — this is Nabokov from 1926 — “to write that there will be a letter tomorrow, because every time when I write this, it doesn’t happen. My darling, I love you. My flight, my flutter.”