From behind a parapet on the tower of Litchfield Villa, the Italianate mansion that marks the western edge of Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, I was barely able to make out — over treetops and tall buildings — a glint of Gowanus Bay, roughly two miles away. Edwin Litchfield, the railroad and real-estate tycoon who built this house in 1857, would have had no trouble seeing the bay and much of his landholdings out of a second-floor window, from the hilly and largely treeless farmland outside his front door all the way down to the grassy banks of Gowanus Creek, which by the late 1860s had been dredged and straightened, at his behest, into a shipping canal.

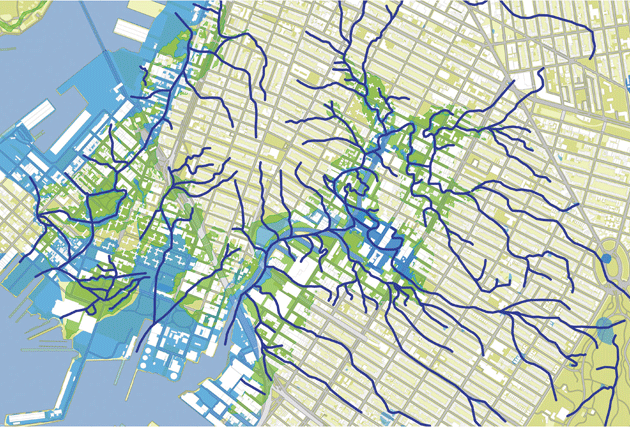

Situated at the bottom of a topographic bowl, the Gowanus marshlands were once nourished by more than a dozen sparkling streams. Most of these rills and freshets haven’t been seen for 150 years; following modern convention, engineers either buried them or corralled them into pipes as they extended the city’s streets. But one of these waterways, I learned after climbing down from Litchfield’s roof and placing my ear atop a manhole cover, still seemed to be flowing, right under my feet.

Photograph of Brouwer’s Brook by Miska Draskoczy, whose monograph Gowanus Wild will be published this spring

“This was the middle branch of what becomes Vechte’s Brook,” said Eymund Diegel, an urban planner, Gowanus gadfly, and self-described pipe geek, as we crossed Prospect Park West at 2nd Street, not far from Litchfield Villa. In his hand was a copy of the 1782 British Headquarters map, over which he had superimposed a 1767 map by the British cartographer Bernard Ratzer, a map of the modern street grid, and his own approximation of the area’s historical streams and springs.

Diegel and I headed downhill, following the blue lines on his map and noting slumping pavement and sudden changes in lot size — all of which suggested clues, if you were in a certain frame of mind, to colonial-era streams that are still asserting themselves today.

The people who live at the lower elevations of this 1,700-acre watershed aren’t always charmed by its hydrologic history. During large rainstorms, those streams contribute to basement flooding, they cause manhole covers to shoot up into the air, and they force a brown froth of sewage up out of tubs, sinks, and toilets. Down at the canal, conditions are even worse.

Like more than 700 other U.S. cities, New York has a “combined” sewage system, which means that rain from the streets joins sewage in underground drainpipes. When the system was designed, more than a century ago, those pipes discharged into local waterways. These days, the flow is pumped to wastewater-treatment plants for filtering and disinfection. But in some areas, as little as a quarter-inch of rain can drown the system. Pipes fill up, plants reach capacity, and untreated sewage, along with storm water, gushes into our rivers and bays.

The Gowanus may be a tiny, filthy place, but its problems with water — too much in the wrong place at the wrong time — are nearly universal. The world over, deluges blow out pipes and culverts, overwhelm treatment plants, contaminate drinking-water supplies, and flood low-lying areas. As cities grow and pave, and as the climate warms — unleashing stronger storms — the drainage crisis will only worsen. But while New York bureaucrats inch through both established and innovative frameworks for taming urban floods, Diegel has come up with his own scheme for using the forces of nature to unpervert the hydrology of the Gowanus and to reanimate a canal long written off as dead.

Wandering along the presumed course of Vechte’s Brook, Diegel repeatedly dropped to the ground to listen at manhole covers and drains. He blurted out contextual clues: that anomalously large tree hinted at a steady water source; a discharge pipe protruding from a school basement spoke to regular flooding. “That’s as good as a chalk outline on a sidewalk,” Diegel said.

When I suggested alternative explanations for these phenomena, Diegel quoted James Joyce: “His errors are volitional and are the portals of discovery.” Diegel bases his streambed predictions on historical maps and paintings, modern flood reports, and computer modeling. He plans to refine his hypotheses by sending remote-controlled cameras underground, injecting dye into known seeps to establish whither they wend, and sampling upwellings for fluoride, which would indicate a leaking city pipe rather than a natural flow.

Diegel told me he was 80 percent confident about the blue lines he had marked on what he called his ghost map. “The massive amount of landfilling and hill cutting makes it difficult to give an exact center to streambeds, plus there were natural meander patterns and fluctuations,” he said. Of the springs he had pinpointed on the neighborhood’s lower slopes, he was closer to 100 percent confident. Soon I would see why.

Several blocks north of Vechte’s Brook, and a stone’s throw from the canal, Diegel and I slipped down a dank and narrow alleyway — think Oliver! — then climbed into the freight elevator of a nineteenth-century factory building. With the turn of a brass wheel, we dropped nine feet below street level and entered another world. The basement was cavernous, musty, and — I was astonished to see — riven by a flowing stream.

“This is Brouwer’s Brook,” Diegel said. He dipped his finger into the current and licked it. “It’s fresh springwater.” According to his 1767 map, the Brouwer spring emerged behind a farmhouse in a nearby meadow. In the 1650s, the brook fed a pond that powered one of the first flour mills in the region. (During the Battle of Long Island, at the start of the Revolutionary War, the colonists burned down the mill to prevent it from falling into British hands; it was later rebuilt.) Today, Brouwer’s Brook rushes across the floor through eight-inch-wide channels hacked into the concrete, before flowing into a pump that shunts the water into city pipes, 24/7, and thence to the Red Hook wastewater-treatment plant.

The stream affirmed Diegel’s cartographic skills; it also illustrated why his work matters. Remove Brouwer’s Brook from city pipes and reconnect it to the Gowanus, and you could reduce sewer overflows and basement backups, lower the canal’s concentration of pathogens, and lighten the workload at the Red Hook plant. The idea has enormous practical appeal. Why pump and filter water that is already clean when gravity would, with a little help, return the brook to its historical outlet?

Back in the Vechte’s drainage, Diegel showed curious passersby, with the help of his map, where the blue ponds and streams of the green Gowanus once lay. Remarkably, not a single person we encountered on a five-hour walk didn’t know what a combined-sewer overflow was. Some even knew about the two-pronged approach that the city’s Department of Environmental Protection had taken to fixing the watershed’s problems: “gray” infrastructure, which includes storage tanks, pumps, and pipes, and “green” infrastructure, which is low-tech, mimics natural systems, consumes far less energy than gray infrastructure, and costs less per gallon to build and maintain.

New York City’s commitment to green infrastructure in the Gowanus is most visible in the ninety or so enlarged tree pits, called bioswales, that collect rain and runoff. Plants in the bioswales sequester or break down the pollutants typically found in storm water — oil and grease, heavy metals, pathogens from dog droppings — and return water to the air through evapotranspiration. Whatever the plants can’t absorb is filtered through eight feet of soil and gravel back into the earth.

“If you take green infrastructure to scale, you’ll achieve a critical mass of storm-water capture,” said Adrian Benepe, the former commissioner of the New York City parks department and a current vice president of the Trust for Public Land. According to the D.E.P., even a 5 percent reduction in the volume of water processed at wastewater-treatment plants would cut the city’s carbon emissions by 15,661 metric tons — the equivalent of taking 3,297 cars off the road. “Distributing thousands of water-absorbing structures around the city, rather than building a few centralized tanks, is just as effective, far cheaper, and more resilient to climate change,” said Tom Ballestero, a civil engineer who directs the University of New Hampshire’s Stormwater Center.

Over the next several years, the D.E.P. plans to create some 5,000 bioswales throughout the city. It also plans to install permeable paving, which allows rain to seep into the earth; replace concrete traffic islands with landscaped planters; and retrofit public parks and schoolyards with porous pavers, synthetic turf, and rain gardens, which are similar to bioswales. All together, the city expects its green-infrastructure initiative to reduce combined-sewer overflows by roughly 3.8 billion gallons a year.

Other cities have taken similar steps. Los Angeles is managing its periodic deluges with permeable pavement and rain gardens that allow water to seep into the city’s depleted aquifer, instead of sluicing it out to sea. The city is also replacing eleven miles of concrete in the L.A. River with green terraces and wetlands. Flood-plagued communities along the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers are restoring natural floodplains rather than hardscaping them with levees. Philadelphia is planting enough bioswales, grassy roofs, and wetlands, at a cost of $800 million over twenty-five years, to make permeable a total of fifteen square miles.

Late in the afternoon, Diegel and I squeezed through a narrow gap in a chain-link fence along Third Avenue, sidestepped across the ledge of a bridge over the canal’s Fourth Street turning basin, and scrambled down an embankment to the dank space beneath the roadway. “This is the historical outflow of Vechte’s Brook,” Diegel said with great solemnity. “This is the last leg of the stream’s marathon, from near Litchfield Villa in Prospect Park through the whole obstacle course of French drains, basement pumps, and the historic landfill.”

I squelched through boot-sucking muck, releasing a whiff of rotten eggs with every step, and took a closer look at the rust-colored flow burbling between concrete slabs. It was impressive not so much for its appearance as its provenance. Many is the time that I’ve watched ankle-deep water race down my block, just uphill from here, and wondered where the rain used to go before this bowl was paved. Now I know: the water flowed into a natural channel that slalomed between hills, growing steadily until it married the Gowanus at roughly this point.

The volume of Vechte’s is low today (it flows year-round), but it could quadruple if a half-century’s worth of rubble, invasive scrub brush, and household trash were excavated from the upland lot. Two hundred years ago, this spot lay near the center of a twenty-four-acre lake that bristled with bivalves and was ringed with salt meadows. Known as Denton’s Mill Pond, it was the defining feature of the Gowanus basin, rising and falling tidally between what would become Second and Fourth Avenues.

The Environmental Protection Agency named the Gowanus Canal a Superfund site in 2010. As part of its cleanup plan, the agency committed to excavating twenty-five feet of these corrupted uplands. But Diegel dreams of exposing Vechte’s Brook nearly to Fourth Avenue. “This is where the water wants to go,” Diegel said, speaking of the thwarted flows that inundate basements and force their way up drains. “Daylighting” streams — removing them from pipes, restoring their riffles and curves, and replanting their banks — raises property values, mitigates local flooding, filters storm water, cools and cleans the air, and provides havens for plants and animals.

Diegel’s vision of a stream winding through this rapidly gentrifying neighborhood may seem quixotic, but projects far more audacious — the High Line comes to mind — have come to pass. “It’s imperative for government to be less dogmatic, to be more entrepreneurial and experimental when it comes to managing storm water,” Adrian Benepe told me. “Government should listen to landscape architects, to scientists, entrepreneurs, and hydrologists who understand how water moves through the soil.”

Landlords with buildings atop the former Denton’s Mill Pond don’t need Diegel or colonial maps to remind them of the area’s soggy history. After the contractors who were excavating the Whole Foods building site at the corner of Third Avenue and 3rd Street hit water five feet down, the company abandoned its plan to build most of the store below grade. Across from the grocery store, at the bottom of a basement stairwell in the Old American Can Factory — an enormous circa 1885 building — Denton’s Mill Pond rises and falls in accordance with rain and the tides. Martin Bisi, a record producer and longtime Can Factory tenant, said that after Hurricane Irene dumped seven inches of rain on the city, “I watched as the water rose six feet in the stairwell, to within inches of my studio door.” During heavy rains, Bisi often hears a spooky rush of water — a branch of Vechte’s, he believes — flowing beneath his feet.

Forty years ago, the Gowanus was a far wilder place. “It was obvious that these were former wetlands,” Bisi recalled. “You could see where nature and human activity rubbed up against each other. But now that there’s this illusion of order here, and it seems humans have it all under wraps, the thought that nature is still timelessly coexisting right under our human plane of city streets is really alluring.”

Diegel folded his ghost map one last time and then extracted from his satchel a copy of a map drawn in 1865 by Egbert Ludovicus Viele, a hydrologist who served as engineer in chief of Central Park and submitted the original plans for Prospect Park. The document shows the streams and marshes of New York City atop its street grid. Many years after completing his map, which is still used today, Viele accused city engineers of making a fatal mistake: they had neglected to provide “a system of drains to carry off this living water that is constantly bubbling out of the rocks on which the city is built, and which will find an outlet somehow.”

Viele didn’t include the Gowanus in his map, but surely he’d understand Diegel’s yearning to free, or at least acknowledge, the watershed’s aboriginal springs and creeks — the hidden arteries that, if you know where to look, still pulse with life today.