Discussed in this essay:

Spain in Our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939, by Adam Hochschild. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 464 pages. $30.

Some eighty years ago, several thousand young Americans went to Spain to fight — and, many of them, to die — in the service of a country that was not their own. Nothing like that had happened on such a scale before, and nothing like it has happened since. They went despite the active opposition of their own government, which would treat them, upon their return and for many years thereafter, as politically suspect. They left jobs, schools, families, sweethearts. They went to enlist on the side of the Republic in the Spanish Civil War, the great cause of the day, joining more than 40,000 other foreign volunteers from some fifty countries. They would go on to suffer a higher rate of combat deaths — more than one in four — than the U.S. military during any of its wars, and would become the first integrated American force to serve under an African-American commander. Their unit, the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, became a fixture of radical legend for decades to come. Lincoln veterans were lionized at antiwar demonstrations in the 1960s and at demonstrations against U.S. involvement in Central America in the 1980s. Their preeminent figure, Robert Merriman, a graduate student at Berkeley when he left for Europe, served as a model for the character of Robert Jordan, the hero of For Whom the Bell Tolls.

Photograph of a meeting of the American Company of the 24th Battalion, Almochuel, September 1937. Courtesy Harry Randall: Fifteenth International Brigade Films and Photographs, Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University

The Lincolns are a natural subject for Adam Hochschild. A civil-rights and antiwar activist in his youth, Hochschild worked as a journalist for Ramparts and cofounded Mother Jones. Since 1990, he has produced a string of historical works on themes of social justice: The Mirror at Midnight, on apartheid South Africa; The Unquiet Ghost, on Stalin’s reign of terror; King Leopold’s Ghost, on the colonization of the Belgian Congo; Bury the Chains, on the struggle to abolish slavery in the British Empire; and To End All Wars, on resistance in Britain to World War I. Hochschild came across half a dozen Lincoln veterans over the years, he tells us, and was longtime friends with two of them. (The unit’s last surviving member turned one hundred in December.) “All of us who care about social justice feel a need for political ancestors,” he writes, “and surely, it seems, that’s what these men and women . . . were.”

Spain in Our Hearts is at its best as narrative and portraiture. Hochschild focuses his story through about a dozen individuals: Merriman, the brigade’s most energetic and valiant commander; Marion, his wife, who joined him in Spain and worked at brigade headquarters; Pat Gurney, a bohemian English artist who fought with the Lincolns and fell in love, to mixed results, with Toby Jensky, an American nurse; James Neugass, an upper-class Jew from New Orleans who became an ambulance driver; the mysterious Vincent Usera, a tall and handsome Puerto Rican officer who had a tendency to desert his men in battle and who may well have been an American intelligence agent.

Surrounding them are journalists such as Herbert L. Matthews, who reported for the New York Times from the Republican zone and often found himself undercut by his editors; William P. Carney, his openly Francoist counterpart across the front; and Virginia Cowles, a beautiful Boston debutante who charmed her way around both sides of the war. Hemingway comes and goes, sometimes with the glamorous and forceful Martha Gellhorn, soon to be his third wife, though despite the novelist’s commitment to the cause and his occasional acts of genuine courage, Hochschild usually presents him in the debunking-condescending mode that’s de rigueur these days. Orwell also appears, not because of any substantial connection to Americans in Spain — one often feels Hochschild straining at the limitations of his source material, the diaries, letters, and memoirs that constitute his primary route to the action — but because the author of Homage to Catalonia provides an irreplaceable witness to the workers’ revolution, led by anarchists and anti-Stalinists, that took place in Barcelona and its environs during the early months of the war.

Spain in Our Hearts is less satisfying when it comes to context and meaning. Hochschild sketches out the causes and course of the war, including the involvement, or, crucially, non-involvement, of the leading powers, but he tells us little of the climate of opinion in the United States — what the press and the public thought about the Lincolns or the broader conflict — or about the leftist milieu from which the volunteers sprang. Most of the larger questions he promises to touch on end up unaddressed, bypassed in the rush of narrative. “What did [the Lincolns] learn — about themselves, about war, about the country they had signed up to defend and the one they had left? Did any have later regrets?” “Did the Republic become doomed by its entanglement with the Soviet Union?” How did its defenders come to terms with that circumstance, and “how much were they even aware of it?” Still, the book provides a brisk and vivid telling of the war, a taste of a uniquely gravid time in history, and a group portrait of a kind of young American who’s almost inconceivable today.

The Spanish Civil War began with a military coup on July 17, 1936. Earlier that year, the Popular Front, a coalition of liberals and leftists, had taken power in parliamentary elections. (Spain had been a constitutional republic only since 1931.) After careful plotting, the generals — who were soon led by a physically unimpressive but masterfully effective veteran of colonial warfare, Francisco Franco — struck back. Within a few weeks, a third of the country, mostly in the south and the west, was under their control.

Terror was a conscious instrument of Nationalist policy. Commanders, Hochschild writes, “spoke of limpieza, or cleansing.” Politicians and trade unionists were bayoneted or shot. Women were subjected to gang rape. Executions often assumed a paranoid cast: in Huesca, one hundred suspected Freemasons were killed; in Granada alone, the death toll amounted to 5,000. Bodies were left to lie as warnings in plazas and streets. All together, some 150,000 individuals were murdered. The generals, as Hochschild says, “brought the colonizer’s mentality back to Spain.”

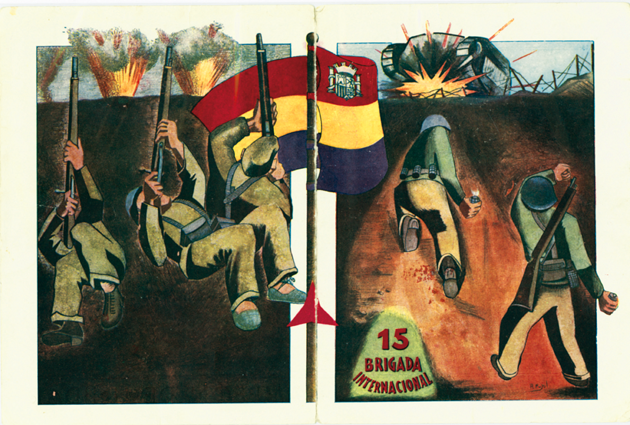

International Brigade commendation card, 1939. Courtesy James Lardner Papers, ALBA No. 67, Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University

Against the Nationalist offensive, the government could muster only a relatively small number of regular troops. The Republic was saved from rapid capitulation by what was essentially a counter-uprising, this one led by trade unions and left-wing parties, many of which maintained, or hastily assembled, their own militias. The units were poorly trained, poorly equipped, poorly organized, and poorly supplied, but their numbers and morale, along with the general spirit of popular enthusiasm (the anarchists alone soon had 100,000 men and women under arms), were enough to stabilize the front.

The Republicans were not innocent of atrocities themselves. Almost 7,000 Catholic clergy — the Spanish Church tilted hard to the right — were put to death. During the first weeks of the siege of Madrid, which began in November 1936 and lasted for more than two years, up to 2,500 suspected “fifth columnists” (the term originated in a Nationalist boast) were taken off and shot. “Centuries of pent-up social tensions,” Hochschild writes, “had erupted in a murderous fury.”

From the start of the war, it was clear that foreign governments would play a crucial role. Hitler and Mussolini, eager to expand their influence, responded at once to Franco’s pleas for help, ferrying Nationalist troops across the Strait of Gibraltar in history’s first large-scale airlift. Over the course of the fighting, the German involvement in particular, especially the provision of aircraft and pilots, proved decisive. Hitler not only gained an ally, he tested weapons, honed tactics, and seasoned his personnel for the coming war. The Spanish conflict saw the debut, among other matériel, of the Messerschmitt Bf 109, the Luftwaffe’s “deadly, versatile mainstay” during World War II, and the Stuka dive-bomber, a new and terrifying kind of weapon. Spanish towns, including one called Guernica, were carpet-bombed by way of experiment. German planes came to dominate the sky, and therefore the war.

The Western powers, meanwhile, were sitting on their hands. The French and British governments, which had complicated interests of their own — not to mention ample numbers of Franco sympathizers among their officer corps — remained aloof. As for Roosevelt, he temporized throughout the war, imposing an arms embargo on both sides that, in practice, hobbled only the Republic. The Depression was re-intensifying, the Spanish Republicans were seen as dangerously radical, and with his popularity declining, FDR was ever mindful of the Catholic vote. Martha Gellhorn’s efforts to influence him through her mentor, the First Lady, came to nothing. Only after the fall of Barcelona, two months before the end of the war and many months too late, did FDR acknowledge that the embargo had been “a grave mistake.”

As it later would with Cuba and Nicaragua, the United States had succeeded in driving a leftist government into the arms of the Soviet Union. With no alternative, the Republic turned to Stalin for support. It was, as Hochschild says, a devil’s bargain. In exchange for arms, the Republicans were forced to accept the presence of Soviet political and military operatives and the increasing dominance of the Communist Party within the ruling coalition. The radical egalitarian experiment in Catalonia and Aragon — “there was no boss-class,” Orwell wrote, “no menial-class, no beggars, no prostitutes, no lawyers, no priests, no boot-licking, no cap-touching” — was suppressed and defamed.

But Stalin also did something that made the story of Americans in Spain possible. Through the Comintern, the international organization of Communist parties, he “passed the word to begin recruiting special brigades of volunteers to fight fascism in Spain.” The Lincolns were certainly idealists, but their story shows that ideals are not enough — not, at least, to get so many men to cross the sea to kill and die. You need an ideology — a belief system — and you also need an organization. “About three quarters of the American volunteers,” Hochschild tells us, “were members of the Communist Party or its youth league.”

There is something else that many of the Lincolns had in common. Almost half of them were Jews. Hochschild’s account is studded with names like Levenson, Silverstein, Barsky, and Wolff. Their involvement underscores the conflict’s larger stakes. “For us it wasn’t Franco,” the Lincoln Maury Colow said. “It was always Hitler.” The Spanish Civil War, which began a few months after the remilitarization of the Rhineland, was fought against the backdrop of the annexation of Austria, the Munich Agreement, and the invasion of Czechoslovakia. It concluded five months to the day before the start of World War II. It was a proxy war not only for Hitler and Stalin but for almost everybody except the Spanish. The decade’s thwarted tensions had assumed a local habitation and a name; its mighty opposites had come to grips at last. “When the fighting broke out,” Orwell wrote, “it is probable that every anti-Fascist in Europe felt a thrill of hope. For here at last, apparently, was democracy standing up to Fascism.”

Among those we come across in Hochschild’s narrative (not all of them in Spain) are John Dos Passos, Orson Welles, Albert Camus, André Malraux, and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry — as well as a Dutch filmmaker, a former Cambridge don, a Swedish labor leader, and the dean of Canterbury. “Because there at least was something to fight for,” James Baldwin would later write about that time of “bewildered and despairing idealism,” “young men went off to die in Spain.”

The first Americans arrived around the start of 1937. Their training camp was near the town of Albacete in the region of La Mancha — a setting that was all too apt for what would prove a tragically quixotic quest. After just a few weeks’ preparation — most of them had never held a gun — they were sent into combat. They had no maps, and the first trucks in the convoy took a wrong turn into enemy territory and “were never heard from again.” They had no shovels, and had to dig their trenches in the rocky ground with bayonets and helmets. They had seventeen types of firearms, each of which needed the right kind of bullet. When the Americans attempted their first advance, they discovered that none of their machine guns worked. Merriman, a graduate of the ROTC, was battalion commander by now. A few days later, he was ordered to lead an advance that he knew would be suicidal. The supporting artillery barrage “had come three hours late and missed its target.” Only three of twenty promised aircraft had appeared, and then only briefly. The flanking battalion of Spanish had quickly withdrawn under fire. Having no alternative, Merriman “led his men out of their trench” and was hit within the first few steps. The battalion as a whole sustained nearly 300 casualties, killed and wounded, out of roughly 500 men.

The Lincolns would participate in half a dozen more engagements, with outcomes that were often scarcely better. For reasons that Hochschild doesn’t explain, the Internationals were always thrown into the thickest of the fighting, with the result that they were killed “at nearly three times the rate of the rest of the Republican army.” What successes they enjoyed were invariably temporary; Republican offensives, which tended to be poorly organized, quickly stalled. Mostly the Americans endured the common soldier’s lot: poor food, inadequate clothing and shelter, insufficient sleep, freezing winter cold, stifling summer heat, mud, lice, boredom, stench, and physical exhaustion. There are a few romantic interludes in Hochschild’s tale — Merriman recovered from his wound and later spent an anniversary with Marion by the seaside in Valencia — but mainly the American experience in Spain, like that of the Republic as a whole, was one of inexorable defeat. In March 1938, a Nationalist offensive broke the Republican line in Aragon and drove the defenders nearly to the sea, a disaster known as the Retreats. Nazi aircraft circled overhead, attacking everything that moved. In the chaos, Merriman, who had been leading his men to the last, went missing in action. His body was never recovered.

That October, in a desperate bid for time, the Republican government withdrew the International Brigades, or what was left of them, from the war, hoping (vainly) that the Western powers would pressure the Nationalists to reciprocate the gesture. A farewell parade was held in Barcelona: “300,000 Spaniards wept, cheered, waved, and threw flowers, confetti, and notes of thanks.” The famous La Pasionaria, Dolores Ibárruri, “the country’s greatest orator,” assumed the podium. “You are history,” she told the Internationals. “You are legend. You are the heroic example of democracy’s solidarity and universality.” But another observer, Hochschild tells us, later drew a different lesson. “Men of my generation,” wrote Camus, “have had Spain in our hearts.” There they learned “that one can be right and yet be beaten, that force can vanquish spirit, and that there are times when courage is not rewarded.”

One American involved with Spain was very happy with the outcome. Torkild Rieber, the chairman of Texaco, was a die-hard Fascist sympathizer. Thanks to Rieber, Franco was supplied with the one essential commodity that his German and Italian patrons could not give him: oil. Provided on credit and often free of transportation costs, the shipments were illegal under the embargo but tolerated by the American government nonetheless. Yet Rieber did more. He employed his company’s global network of offices and agents to pass on intelligence about shipments bound for the other side, allowing the Nationalists to attack or seize Republican oil supplies. Texaco, Hochschild writes, “had gone to war.”

Rieber was hardly alone among his class in his enthusiasm for the Fascist cause. When Franco won, Orwell later wrote, “the dividend-drawers all over the world rubbed their hands.” Upon the fall of France (which took place less than fifteen months after the surrender of the Spanish Republic), Rieber and Gerhardt Westrick, in Hochschild’s words a Nazi “lobbyist-cum-intelligence agent” who worked out of Texaco headquarters in New York, participated in a celebratory dinner at the Waldorf-Astoria in the company of executives from Ford, General Motors, Eastman Kodak, and other corporations. Rieber, who died rich at the age of eighty-six, later played host to Franco’s daughter and son-in-law when they visited the United States. As for the Generalissimo, he ruled Spain — brutally, in an increasingly monarchical style, and, after 1953, with American support — until his death in 1975.

What are we to make today of the Spanish Civil War and of the young Americans who went to fight in it? The conflict feels very distant now — more distant, I think, and certainly more alien, than some that are older, like World War I. It was a war of interests, like every other, but it was also, especially for those who came from other countries, a war of beliefs. And we don’t have that kind of relationship, any longer, to beliefs. Who among us, of any age, would put their lives at risk like that: not to protect their country or their family, but simply for an idea — simply for justice, simply for democracy?

Of course, the answer depends on whom you mean by “us.” There are young Americans who are willing to fight and die today for a foreign cause, for the sake of belief: those who are going off, against the opposition of their government, to join the Islamic State and other extremist organizations — some 250 so far, according to a recent count, joining more than 25,000 other foreign nationals. No doubt the Jews and Communists who went to fight for Spain looked just as hideous to many Americans then. That doesn’t mean the two are morally equivalent, but it does suggest the way that things have changed. Fewer than a dozen Americans fought for Franco, whose Falangist ideology also blended elements of authoritarianism, religious fanaticism, and the worship of violence. Now the energy is on the other side.

Orwell blamed the complacency of the liberal intelligentsia on its comfortable remove from unpleasant necessities. “We have become too civilised to grasp the obvious,” he wrote in 1943, in an essay titled “Looking Back on the Spanish War.” “For the truth is very simple. To survive you often have to fight, and to fight you have to dirty yourself. War is evil, and it is often the lesser evil.”