Discussed in this essay:

Slash, by Slash with Anthony Bozza. It Books. 480 pages. $16.99

It’s So Easy: And Other Lies, by Duff McKagan. Touchstone. 384 pages. $17.

My Appetite for Destruction: Sex & Drugs & Guns N’ Roses, by Steven Adler with Lawrence J. Spagnola. 304 pages. It Books. $17.99

Watch You Bleed: The Saga of Guns N’ Roses, by Stephen Davis. Avery. 480 pages. $17.

W.A.R.: The Unauthorized Biography of William Axl Rose, by Mick Wall. St. Martin’s Griffin. 384 pages. $19.99

The original recording lineup of Guns N’ Roses — rhythm-guitar player Izzy Stradlin, bassist Duff McKagan, lead guitarist Slash, drummer Steven Adler, and singer Axl Rose — released a total of eighty minutes and nineteen seconds of original music: twelve songs on Appetite for Destruction, the band’s 1987 debut album; four more on GN’R Lies, which was released the following year; and one final song, “Civil War,” on a 1990 compilation album. Appetite for Destruction, Guns’ creative and commercial peak, has sold more than 21 million copies — it remains the best-selling American debut album in history — and Lies another 7 million. It is difficult to think of another rock act that became so influential and popular while producing so little music.

Despite the reunion tour that kicked off last month — Axl, Slash, and Duff are back together onstage for the first time since 1993 — Guns as a vital, creative force has been spent for more than a quarter-century. The story of the band’s rise and what virtually everyone besides Axl Rose considers a great fall has now been documented in several biographies and memoirs. Duff, Adler, and Slash have all written, or had ghostwritten, their version of events. These accounts, along with several books by rock journalists — in particular those by Stephen Davis and Mick Wall, a onetime Guns confidant — make it possible to tease out the story of a band that was, for a time, that rarest of parlays: one of the most popular rock and roll groups in the world, and arguably the best.

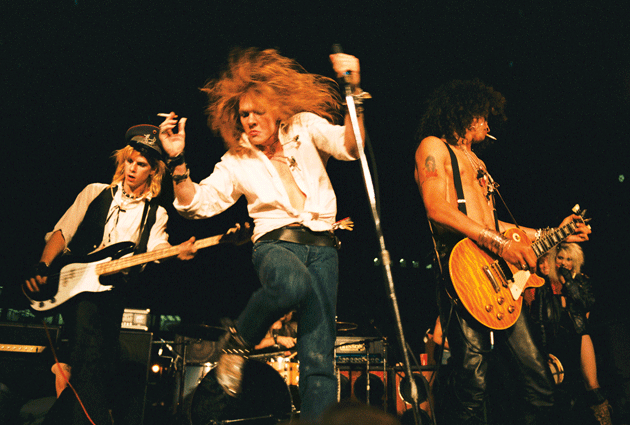

The emergence of Guns N’ Roses as a global phenomenon, which followed the release of Appetite, owed much to their invention of a sound that was at once fresh and reassuringly familiar. The band’s provenance (Hollywood’s burgeoning Sunset Strip club scene) and their look (big frizzy hair, aviator sunglasses, leather chaps, cowboy boots) seemed to situate Guns as the latest in a long line of glam-metal bands — Quiet Riot, Ratt, Mötley Crüe, Poison, Warrant, White Lion, Cinderella — that had been foisted on America’s teens by MTV. By the mid-Eighties, guitar rock played by skinny men in tight pants with gravity-defying hairstyles had become so unexceptional that Appetite was largely ignored by the rock press when it was released, in July 1987. Rolling Stone didn’t even bother to write a review; it’s easy to imagine an editor taking one look at the band’s carefully cultivated “dangerous” image and dismissing the group as yet another attempt by a record label to squeeze money out of what had become a tedious and predictable genre.

The truth, however, is that Guns — or at least the three members who have so far produced memoirs — despised hair metal. And yet without the existence of a commercially viable rock scene, which produced dozens of forgettable bands, Guns might never have gotten its chance. Nor would American teens, who by then had been sold so much bogus hard rock that the real stuff was like a taste of pure cocaine after years of mannitol. As Chuck Klosterman writes in Fargo Rock City: “Appetite for Destruction is the singular answer to the question, ‘Why did hair metal need to exist?’ ”

I first saw Guns in the summer of 1986, at the Troubadour in West Hollywood. The PA system blared the theme to 2001: A Space Odyssey before the band came onstage, and when they did, they were so loud that I couldn’t pick out the melody or chorus of any of the songs. Even the covers they played, such as Aerosmith’s “Mama Kin,” were unrecognizable. From Reckless Road, a photo-history of the band by Marc Canter — the proprietor of Canter’s Deli, in L.A., a lifelong friend of Slash (né Saul Hudson), and an early source of financial and caloric sustenance for the band — I have deduced that the show must have been on July 11, and that the set list included nearly every song that would end up on Appetite a year later. My most vivid memory is of Axl Rose — has there ever been a better nom de rock, with its evocation of a metal pole impaling a flower? — who was then androgynously beautiful. Aside from the long red hair on his head, he seemed shaved everywhere else, and to be intentionally subverting gender norms. For a person who wrote some pretty homophobic lyrics, Axl in his crotchless chaps knew how to play a leather rent boy to the hilt.

Axl is the enigmatic figure at the center of nearly every book written about the band. He was born in 1962 in Lafayette, Indiana, to Sharon Lintner, a sixteen-year-old unwed mother, and William Rose, whom Stephen Davis describes in Watch You Bleed as a “troubled and charismatic local delinquent.” Lintner later married a Pentecostal preacher named Stephen Bailey, who raised Axl as his son. Axl — or Bill Bailey Jr., as he was known then — was a gifted member of his local church choir, able to sing an unusually large range of vocal parts with equal facility. His father’s strict household rules meant that he could listen to rock music only under the covers at night. At sixteen, Bill discovered the truth about his father. The revelation led him to distrust authority in all its forms and seems to have accelerated an adolescence of petty crime, which resulted in several stretches in adult jails. Local police and prosecutors, tired of detaining the young hoodlum, eventually sought to put him away for thirty years. Instead, he fled to Los Angeles, where he joined Izzy Stradlin (né Jeffrey Dean Isbell), a high-school friend who had recently lit out for California, and began calling himself Axl, after the name of a band he’d played with in Lafayette. Axl brought his authority problems with him to Los Angeles, along with the makings of his tragic flaw: an unwillingness to surrender his prerogative in any circumstance.

In each of these accounts, Axl appears angry, capricious, and imperious. By the time Guns achieved its first successes, Slash and Duff had already grown wary of trying to curtail his behavior, in part because their own addictions to drugs undermined their credibility. (For all of Axl’s personal and psychological travails, he does not seem to have been a drug addict.) By his mid-twenties, Axl was on his way to becoming a version of the authority figures he had once bridled against, demanding total control of the band, forcing his bandmates to legally sign over ownership of the name Guns N’ Roses, lecturing audiences from the stage like an angry high-school principal. This authoritarian streak eventually led to the resignation or firing of every other original member of the band.

In W.A.R., Mick Wall quotes Izzy Stradlin’s suggestion that Axl’s adult excesses were rooted in his childhood struggles. He was

just a little guy, who sings, is talented. But man, he turned into this fucking maniac! . . . For [Axl] the money wasn’t as big a deal. But he had this power thing where he wanted complete control. And you can say, well, it goes back to your fucked-up childhood, and he had no control, so now he’s getting it back.

The memoirs by Duff, Adler, and Slash and the biographies by Davis and Wall all describe a thousand-mile journey from L.A. to Seattle in 1985 as the crucible of the band. Duff, the most experienced musician of the group, had booked a mini-tour for Guns, a West Coast jaunt that would include club dates in Seattle, Portland, and San Francisco, with the band sleeping on floors and their instruments and equipment in a U-Haul hitched to the back of an Oldsmobile.

The car broke down a few hundred miles north of L.A., outside Fresno. The roadies — basically friends who were doing them a favor — agreed to wait for the car to be repaired, while the band decided to hitchhike the remaining 800 or so miles. Dressed in leather and denim, and generally lax about their personal hygiene, they were picked up by an amphetamine-abusing trucker, fed themselves by raiding an onion field, and slept outdoors. Somehow they made it to Seattle in time to play before a dozen people at Gorilla Gardens. Duff writes that the manager stiffed them out of the $200 they’d been promised, and that he attempted to set fire to the club in retaliation. (He failed.)

On returning to Los Angeles, the band began rehearsing twice a day, gigging furiously around town, and building the material that would appear on Appetite. At the time, four of the five were crashing in a storage space off of Sunset Boulevard that they had converted into a rehearsal room with a rickety wooden sleeping loft. I visited the space once; Slash was doing tricks on a BMX bike.

The scene around Guns would’ve been familiar to anyone who had spent time in the punk scene, but instead of the communal ethos that reigned in some punk houses, there was a clear hierarchy here. At the top were the guys in the band, who would hit up friends and acquaintances for whatever resources they needed — money, drugs, alcohol. That this arrangement was a means to an end — their own success — made them seem more like grubby little capitalists than young revolutionaries. Indeed, Guns never had a political agenda. They were first and foremost about themselves and their music — and that self-focus affected their dealings with every civilian who came into their orbit. Living in close quarters, on just a few dollars a day, the band became resourceful; they even improvised a cure for their rampant cases of venereal disease. “You could get dirt-cheap antibiotics — intended for use in aquariums — at pet stores,” Duff McKagan writes. “Turned out tetracycline wasn’t just good for tail rot and gill disease. It also did great with syphilis.”

If there is one fact that undermines Axl’s sense of his own importance, it is that the members of Guns N’ Roses shared equal writing credits for every song on Appetite. The music arose, as even Axl conceded, from their communal experiences: the journey to Seattle, the L.A. storage unit, alcoholism and drug addiction, sex with groupies. They felt themselves to have, as Slash puts it, “a gang’s sense of loyalty.” Their manager had wisely decided to have Guns record at a studio in the Valley, a difficult commute from Hollywood for a band that, remarkably, had named Slash as their designated driver. They bivouacked in corporate housing, which they destroyed, but they wrapped up most of the recording in just a few weeks. Along with Mike Clink, the band’s producer — who got the gig after Paul Stanley of Kiss was found wanting — GN’R was striving for a live-sounding record, and for the most part they succeeded.

Appetite for Destruction might be described as a concept album, since it possesses a thematic coherence and an operatic arc. The first side opens with “Welcome to the Jungle.” Izzy Stradlin’s Bo Diddley–esque riff is the heart of the song, while Axl, whose voice is a combination of Janis Joplin and Edward G. Robinson, serves as cicerone for a descent into a decadently glamorous hell. From there, we proceed through the carnal bliss and joyful imbibing of “It’s So Easy” and “Nightrain” to the paranoid visions of “Out ta Get Me,” which are brought on by the addiction spelled out in “Mr. Brownstone,” before finally ascending to the sweet oblivion of “Paradise City.” Musically, the band is a perfect rock machine — Axl’s voice a melodic snarl, the twin guitars playing off each other, the back line tight and driving. Duff sets the tempo on most songs, with Steven Adler dragging just a millisecond behind. (Slash writes that Adler is watching his left foot to keep time, while also getting cues from Duff for drum fills.) Adler’s swishy beat is essential to the Guns sound; the way he rides his high hat a tiny fraction behind loosely leashes the songs, allowing the other players, Slash in particular, to breathe and take some chances. It also gives the album a bluesier feel than what was typical at the time.

But it’s the lyrics that make Appetite a unique heavy-metal album. Unlike his hair-metal peers, Axl was singing about real life, not wizards or devils or looks that kill or cherry pies. Take this verse from “Nightrain,” a song ostensibly about fortified wine:

Well I’m a west coast struttin’

One bad mother

Got a rattlesnake suitcase

Under my arm

Said I’m a mean machine

Been drinkin’ gasoline

An honey you can make my motor hum

I got one chance left

In a nine live cat

I got a dog eat dog sly smile

I got a Molotov cocktail with a match to go

I smoke my cigarette with style

That could be something out of the great American songbook, Cole Porter perhaps, by way of Charles Bukowski.

This, from “Mr. Brownstone,” sounds both familiar — it has the playfulness of an Ella Fitzgerald number — and like an utterly novel account of the cycle of addiction:

I used ta do a little but a little wouldn’t do

So the little got more and more

I just keep tryin’ ta get a little better

Said a little better than before

While Slash’s narrative is the most vivid and poetic, and Duff’s the most earnest, the saddest has to be Adler’s. At one point during the recording process, Axl refused to keep working because he didn’t feel the royalty split was fair. “He believed he was entitled to more than the rest of us,” Adler writes. “The other guys were smart. They just stared at the floor. No one said a fucking thing.” According to Slash, Axl said, “There’s no way Steven gets twenty percent, the same as I do.” Adler volunteered to give up 5 percent of his royalties so that Axl could have 25 percent. “I think Steven was permanently scarred by that,” Slash writes.

In 1989, Axl decided that the band should move to Chicago to make a new album, reasoning that it was closer to Izzy, who had moved back to Indiana. Slash, Duff, and Steven rented a condominium in Chicago that had a nightclub downstairs and a recording studio down the street. The three of them jammed together for nearly six weeks, developing material for what would become Use Your Illusion I and II. Axl, who was chronically tardy, took his time arriving. It was during this period that Slash and Duff began to freeze Steven out. The two “would go in some other room to party,” Steven writes:

I would begin to follow them only to find that they had shut the door on me. . . . I have no idea why, other than I felt they believed I just wasn’t cool enough to hang out with anymore. I ended up doing my blow all alone while they partied together.

When Axl did arrive, he plinked some of the chords for what would become “November Rain,” appeared largely uninterested in what the rest of the boys had been working on, and eventually trashed their condo and studio. The band was effectively finished as a democratic, collaborative artistic enterprise. Steven Adler was fired soon after for drug abuse.

The rest of the songwriting and recording for Use Your Illusion was as bloated and baroque as Appetite’s had been lean and efficient. The band members rarely saw one another, recording their own parts to songs in adjacent studios. Axl arrived late with his entourage to record the vocals. He also determined the final versions of each song as well as the overall shape of the albums. By then, he had taken complete creative control, and the result was grandiose, overproduced music. If Appetite was all killer, no filler, as the punks used to say, then the Use Your Illusion project was the opposite. Even Izzy was stunned when he heard the finished version of the albums. (The band received them at roughly the same time that they were released to the general public.) He discovered that a new song, a garbled, frantic, half-baked fragment called “My World,” apparently an Axl solo work, had been added to the end of Use Your Illusion II. Take a moment and listen to it. It’s a perfect encapsulation of how much had gone wrong with Guns by then.

Guns N’ Roses were the last massively popular rock band that was able to capitalize on a music industry that hadn’t yet had its business model destroyed by digitization. They were uncynical about the nature of commercial success, incurious about the role of the rock star in society, and never bothered with much introspection around their own celebrity. That naïveté may have helped propel them to make one of the greatest rock albums in history, but it also allowed them to succumb to every rock-star cliché, including debilitating drug addictions, feuding band members, and, finally, a mercurial lead singer who came to believe he didn’t need the rest of the original band. It turns out he did.