Before she showed Pop paintings at the Whitney and the Guggenheim; before her madcap plays were performed at the Judson Poets’ Theater and La MaMa; before she traveled the female wrestling circuit as Rosa Carlo, the Mexican Spitfire — before all that, Rosalyn Drexler was Rosalind Bronznick, a Jewish girl from the Bronx with a wimple of sprayed hair. In her teens, she studied piano and voice because her family wanted her to be a star like her uncle Chico Marx, but she never made it to Hollywood. Instead, she had walk-on parts in “Midtown hotels where distant relatives and businessmen dangled college money and felt her up.”

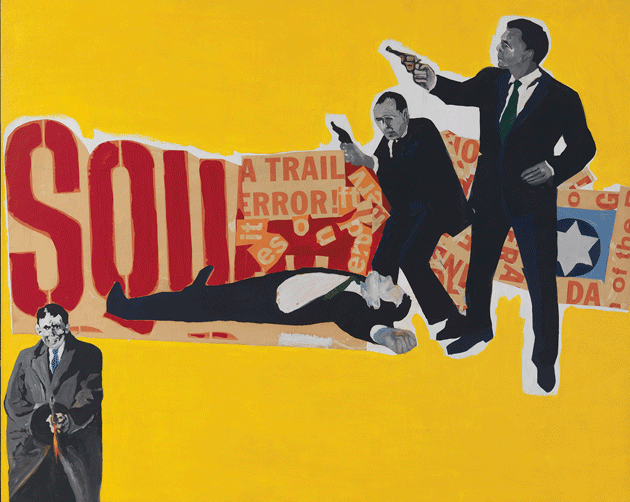

The Defenders, by Rosalyn Drexler © The artist/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City. Courtesy the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York City

Well: in ROSALYN DREXLER: WHO DOES SHE THINK SHE IS? (Gregory R. Miller & Co., $50), the catalogue for a retrospective of her work at Brandeis University’s Rose Art Museum, which closes on June 5, the art historian Katy Siegel makes it clear that there’s more than one way to be a star. Drexler’s roles also included sculptor of wire-and-found-object assemblages, participant in happenings at the Reuben Gallery, and author. She published novelizations of Rocky and assorted TV movies (See How She Runs, Unwed Widow, Alexander: The Other Side of Dawn) under the pseudonym Julia Sorel; under her own name, she issued funny, fragmentary fictions, including I Am the Beautiful Stranger, a coming-of-age story about an adolescent and her older lovers, and The Cosmopolitan Girl, a sex comedy about a woman and her dog.

The child of Russian immigrants who stocked their home with middlebrow treasures — a deluxe dictionary, a print of a Turner seascape ordered from the newspaper — Bronznick dropped out of Hunter College to marry a painter named Sherman Drexler in 1946. Who Does She Think She Is? has little to say about Sherman, but he doesn’t seem to have stood in the way of Drexler’s fun. Shortly after they moved to 49th Street, she started practicing judo at Bothner’s Gymnasium, where suits lifted weights next to carnival performers, among whom there were, according to the art historian Allison Unruh’s contribution to the catalogue, “dwarfs tumbling, an old lady in a tutu who hung from the ceiling, and a man who rode a unicycle as his wife performed a headstand on his head.” In early 1950, Drexler began wrestling. A 1957 spread for Ultra magazine, “From the Private Photo Album of a Mat Queen,” shows her modeling in brassiere and garters, and hunched in a staggered stance. Her expression is impish, her hands open, and her fingers flexed, as if to say, Come and get it! Her friend Andy Warhol copied this image for a silk screen — a dozen ghostly, crouching Drexlers in red and blue, ready to vanquish life or scoop it into a crushing bear hug.

Portrait of Rosalyn Drexler, by Rosalyn Drexler © The artist/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City. Courtesy the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York City

“I wasn’t trying to be an artist, be a writer,” she told an interviewer in 1975. “I wasn’t even trying to be a wife. All these things are a sorta natural process to me.” Drexler’s notion of the natural was playful and dark, idiosyncratic and mass-produced. She began making sculpture in the mid-1950s, and a few years later turned to painting. Her method was bricolage. She would paste blown-up reproductions of clippings and photographs onto rich monochrome backgrounds and paint over them with acrylic. The sources she chose were generally “vulgar” — B-movie posters of G-men, gangsters, or molls, as well as newspaper advertisements, Weegee photos, and images of boxers. Many of her canvases feature a man and a woman locked in an embrace that could be rape or seduction, or one person stalking or striking or holding down another. Drexler’s figures tend to be caught mid-gesture, with an arm flung out or raised high, but their bodies are often placed off-center, so that they seem to be falling into an abyss. “My pictures are like ice floes,” she said, “jarred loose and floating nowhere. On them, the people act violently, but their foothold is melting.”

Drexler does not treat her themes of power, sex, violence, abuse, and jealousy despairingly. “I perform rescue work,” she said. “I peruse the sewer with wonder and love.” And with a wicked, deranged sense of humor. In her novel To Smithereens (1972), a groper named Paul hides out in the men’s room at the movie theater, glued to the toilet and contemplating his pleasures: “As I so often ask myself, ‘Dear God, why do I get hot for big?’ The very question gets me hot. To be overcome by big! To be handled roughly by the last in line, the funky fat, the tough tomboy!” In the play Room 17C (1984), Linda Normal, based on Linda Loman from Death of a Salesman, shares a hotel room with a seductive cockroach named Sammy Gregor (ahem). When her son catches them together, he demands to know, “What does he have that Dad doesn’t?” Linda’s response: “Feelers! He has feelers!”

It’s hard not to read a scene from the play The Writer’s Opera (1979) as Drexler’s ars poetica. Susan, a woman in her early forties, comes onstage pushing a shopping cart filled with newspapers and magazines. Armed with some paste and a pair of scissors, she begins cutting out words and arranging them into a list. She sings:

If you want to be a writer

Learn to cut and paste

Nothing is worth saving

but waste.Any small scrap

might carry within it

a great ideaSo whatever you find

that’s broken

splintered

or loose,

gather it up

make it whole

tape it down . . .

Intelligence and wit bind all of Drexler’s work, as strong as crazy glue.

I can’t say for sure, but I think Bernadette Mayer would approve of Susan’s song. Mayer’s new collection, WORKS AND DAYS (New Directions, $15.95), mixes poems and journal entries, glorying in both the burgeoning of spring and the accidents and irruptions of language. “It’s Arbor Day eve,” she writes on April 24. “Words chosen at random by cutting circles in a piece of paper placed over workshop’s poems. Making syntax not sense, the illusion of sense. It’s like going to the weight room. I think the bluebirds will occupy that house.”

Mayer, who has been publishing what they call avant-garde poetry since the late Sixties, is an artist of rhythms and record-keeping. She is known for projects like Midwinter Day, a book-length poem she wrote in one day in 1978, and the gallery show Memory, which exhibited the rolls of film that she shot every day for a month in 1971. The first piece in Works and Days is a twenty-five-item list of “Payment for some Mohican land”: 300 guilders in sewan, twenty scissors, one barrel of beer, etc. This prepares the soil for what follows: local history, some energetic railing against ecological disaster and Wall Street, complaints about “the guy who bought the field” and turned it into “a white man’s manicured lawn,” the assertion that “property is robbery,” and reports from daily life. “Not only that, it’s Sunday and the local paper didn’t arrive,” reads the entry for June 1. “Now it did: it’s still Sunday though.”

Talking about these poems is less interesting than hearing them, so I’ll quote a stanza I like and you can read it aloud. This one is from “The Sexual Organs of the IRS”:

I got a supernova for xmas

It had two sides, it glowed, I shared

It with my sister, it made our vaginas feel good

At first we were shocked like when you see a creek monster

But soon we noticed we had become spaceships

Cruising into jello like a grape or pear piece

In “Frigidusaphobia,” she jokes: “Mrs. Field / Oil fields / Hay fields / Field guide to.” On June 14, she makes a list: gooseneck LED light, matrix display, hot-air-station nozzle, power-entry module.

Like the first poet, Adam, Mayer names what she sees. Reading her logs, I was reminded of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s list of “Descriptions of Things and Atmospheres.” Between “Cluster of murky brown doors so alike that to be identified it seemed that hers must be counted off from the abutting blackness of an alley” and “On the sky-blue sky, the clouds low above the prairie, the grand canyonesque architecture of the cliffs, the cactus penguins extending conciliatory arms,” Fitzgerald notes down the phrase “Listless disorder.”

To be listless, or list-less, is indeed to be disordered, but to be listful may be to have merely the appearance of order. Some lists are precious inventories, like the Book of Life; some are catalogues, like Homer’s roll call of ships; others aspire to their own erasure, achieving completion only when everything on them has been crossed out. Mayer’s diary for April 24 concludes, as many of them do, with a puzzling list, a few lines of anagrams. Here’s a sampling:

sliposwrapl kimps vleebcorrus dulgesvhlys

fatsf cucorn tgent tnegot ydold dlody chumh

The book’s introduction explains that these are “seemingly random agglomerations of letters from a daily word game, the jumble.” I was able to figure out a couple of them: “skimp” was one; “staff” was another. Then I gave up. Not all jumbles need to be unraveled. I suspect that some of Mayer’s are straight-up tricks. Perhaps they are a way of crossing words out before they have even been written down.

Unlike Drexler’s merry anarchy, Mayer’s delight in wordplay, or Fitzgerald’s listless disorder, the lists in Dorthe Nors’s SO MUCH FOR THAT WINTER (Graywolf Press, $15) are used to radically focus narrative — they pare it down and, by doing so, give it more, rather than less, structure. The first novella, “Minna Needs Rehearsal Space,” is told in a series of short, third-person sentences that have the feel of status updates. It begins:

Minna introduces herself.

Minna is on Facebook.

Minna isn’t a day over forty.

Minna is a composer.

Minna is soon dumped by Lars, a cultural journalist, when he falls for Linda Lund, another musician, whose “sex appeal is undeniable,” and the narrative expands, like the “paper sonata” Minna is writing, to incorporate new lines and tones, notes that rise and fall contrapuntally. Minna deals with her family; Minna takes herself on a vacation; Minna sings on the beach.

Parataxis — the simple plotting of one thing after another — has become a popular literary mode. Recent books by Maggie Nelson, Sarah Manguso, Heidi Julavits, and Jenny Offill have all played with the diary or list form. And in Karl Ove Knausgaard’s serial novels, memories follow one another with only the most tenuous associative links to suture them together. But in Nors, what looks like parataxis is in fact causal, connected. These lists are shaped like arrows:

The song disappeared, down toward the bottom.

The song stands still among the herring.

Everything else belongs to another reality.

Everything else, Minna thinks to herself, is mere geography.

The climax arrives when Minna hits her head on a rock and almost drowns.

Like Minna, the narrator of the second story, “Days,” is lonely — a single, childless woman of late childbearing years navigating the daily routines of a creative life. In three dozen diary entries, which average fifteen or twenty numbered components each, she undergoes oral surgery, rides her bike, runs, gets annoyed with a friend, has a birthday, sees her parents, cries. She craves contact with nature, and achieves it in the cemetery:

12. Stopped by Kyhn’s grave on the way back, and it was the roses,

13. centifolia, multiflora, and Astrid Lindgren, and there I stood and set aside everything I hoped for, and it was as if he turned his head from his verdigris bronze plaque and gazed down at me:

14. Why, there we have you then, woman,

15. hoverflies about your face

16. and utterly alone.

The problem in “Days” is not that life is arbitrary, as numbers are, but that the narrator is responsible for its meaning. The meaning she finds is not in the things she does or the places she goes or the blooms that solace her but in her writing about it all; not in life but in art. She cuts and pastes experience into a pattern, a form. The “Days” of her title are not just any days — “Muffled and dumb like barefoot dervishes,” as Emerson said. They are her days:

12. I felt listened to

13. and loved beneath the surface,

14. and bore in mind the thought that for God, a gravestone is just a scrap to make notes upon, the way the rest of us write our small concerns on the papers on the desk,

15. and one thing is inescapable: I write,

16. I write

17. centifolia, multiflora, and Astrid Lindgren.

18. That cannot be changed, I thought

19. and skirted the high-piled Midsummer Night bonfires, smiling (demented)

20. across the hay-scented lawns home.