Discussed in this essay:

A Visit to Don Otavio: A Mexican Journey, by Sybille Bedford. NYRB Classics. 392 pages. $18.95.

A Legacy, by Sybille Bedford. NYRB Classics. 384 pages. $16.95.

Quicksands: A Memoir, by Sybille Bedford. Counterpoint. 384 pages. $14.95.

“Whenever I can I bring my own provisions,” Sybille Bedford wrote in A Visit to Don Otavio, her lightly fictionalized account of a trip to Mexico in 1946. “It keeps one independent and agreeably employed.” At the start of the book, she boards the train in New York City, with her hamper well stocked:

I had got us some tins of tunny fish, a jar of smoked roe, a hunk of salami and a hunk of provolone; some rye bread, and some black bread in cellophane that keeps. That first night we had fresh food. A chicken, roasted that afternoon at a friend’s house, still gently warm; a few slices of that American wonder, Virginia ham; marble-sized, dark red tomatoes from the market stands on Second Avenue; watercress, a flute of bread, a square of cream cheese, a bag of cherries and a bottle of pink wine.

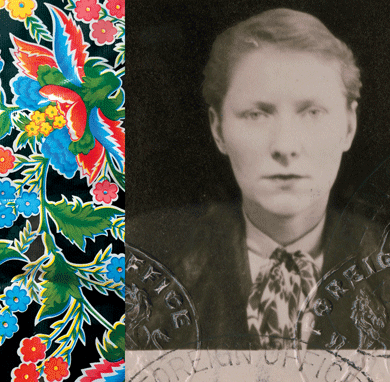

Source photograph from Sybille Bedford’s passport courtesy Harry Ransom Center, the University of Texas at Austin

She even brings her own pepper mill, loaded with whole Tellicherry grains. “Have an olive,” she suggests to her traveling companion, before comparing her pampered self to a dachshund in Paris she once heard about, who wore a coat with a monogrammed handkerchief in its pocket.

The passage shows off the virtues of Bedford’s prose: unfussy diction (if there are two hunks, why be shy about repeating the word?), a relish for abundant, precise detail (the warmth of the chicken, the shape of the bread), frank appetite, and light irony. There’s also a note of excess, and that, too, is a virtue: Bedford was a sensualist, unabashed about the pleasure she took in food, wine, sun, swimming, literature, history, painting, conversation, and romance (in her case, mostly with women).

Anyone willing to take pleasure seriously can have this much fun, her memoirs and autobiographical novels, which NYRB Classics has begun reissuing, seem to say. Her hedonism wasn’t that of a spoiled child but of someone who, often abandoned as a girl, found that she enjoyed the freedom of fending for herself. It’s an enlightened, civilized, and even prudent hedonism. Why not make the best of there being, in the end, no one but oneself to see to it that one doesn’t go hungry?

Bedford, an English writer of German birth, occasionally let more than a dozen years pass between books, and in her own lifetime she was acclaimed, forgotten, and rediscovered repeatedly. In 1994, Britain’s Royal Society of Literature bestowed on her its highest honor, not given to more than ten writers at a time — and since then, the cycle of forgetting and recovery has revolved at least twice more.

Pleasure and loss were complexly interwoven in her life story, which she unraveled and restitched every time she told it. “A writer writes his past away,” she once explained. “Yet something keeps smouldering on.” She was born in 1911 in what is now a neighborhood of Berlin. “It was a boy?” a version of her mother asks in her first novel, A Legacy (1956), while recovering from labor. “No. Yes,” the fictional mother is told, as if even at Bedford’s birth there was a hint that she wasn’t going to conform to gender norms. The family’s nickname for her was Billi.

Her father, Maximilian Josef von Schoenebeck, was a German baron in his late forties who liked to gamble, womanize, speak French, and collect Gothic and Renaissance objets d’art — a sort of benign Gilbert Osmond. The family’s nickname for him was le beau Max. Bedford describes him as a man who had “lost his nerve.” Long after his first wife died of tuberculosis, he continued to live off her stodgy, generous parents, Jews who maintained a stuffy house in Berlin. After their fortunes collapsed, he was supported by his second wife, Elizabeth, née Bernhardt — Bedford’s mother, a British heiress and beauty who went by the name Lisa. She was younger than he, and her eye wandered as freely as his. In A Legacy, she cuts a dashing and charming figure, but Bedford’s portrait of her darkened over the years, and eventually Bedford would describe her as a “writer manqué” whose moods could be tyrannical. “I did not love her as a child,” Bedford admitted to one interviewer. To another, who happened to share her mother’s name, she confessed that she was reluctant to say it aloud.

During World War I, husband, wife, and child sheltered in Berlin, and after the war they moved to a small château in southern Germany. One day Lisa went away with a lover and never returned. The money went with her. All but one of the servants were let go; all but a few rooms were shut. Billi, who was around eleven, ran away, but after she was found at her half-sister’s house and gently returned to her father, she discovered that she was able to reconcile herself to living with him. Maximilian was an excellent cook; decades before Elizabeth David, he believed in liberating ingredients from the heavy sauces that the Victorians had poured over them. Chronically short of cash, he was nonetheless able to provide for the household by raising sheep, chickens, and pigs and making cider and white wine. In the evenings he took out a vintage roulette wheel, cried “Faîtes vos jeux,” and reminisced as he, Billi, and their lone devoted maid gambled. When Lisa at last decided to exercise her right to spend time with her daughter, several years later, Billi didn’t want to go.

She was made to. A chaperone escorted her to a hotel in northern Italy. Lisa had been planning to marry an art historian, but she now absconded, in pursuit of an architecture student half her age. The chaperone absconded, too. “What if nobody came back?” Bedford later recalled wondering, in her memoir Quicksands (2005). With two Swedish children also staying in the hotel, she begged in a city park on behalf of a make-believe charity. In the end her mother did return, taking her to Naples and then Sicily with the architecture student, whose name was Norberto Marchesani.

At around the same time, Billi’s father died, following an operation for appendicitis. Authorities in Germany became legally responsible for her and insisted that she be given an education. As it would turn out, she had already received as much classroom schooling as she would ever get, but, to oblige the authorities, her mother sent her to England, where she lodged with a couple of amiable, broke artists whom Lisa had once met at a hotel. While Billi was away, her mother and Marchesani moved to southern France, choosing the coastal town of Sanary-sur-Mer more or less at random.

So began a cosmopolitan, little-supervised adolescence, yo-yoing back and forth across the English Channel. In England, Bedford vicariously enjoyed the romantic lives of adult friends, visited courtrooms in order to soak up what she called a “blend of gravity and theatre,” and was intermittently tutored. In France, she swam, fell unrequitedly in love with the wife of an older friend, and got to know such neighbors as Aldous and Maria Huxley, who had come for the Mediterranean sunshine, and Klaus and Erika Mann, who were fleeing Hitler. The idyll ended when her mother, upset by an infidelity of Marchesani’s, started using morphine.

Bedford knew her vocation early on. “To write, to be a writer, had been the true goal ever since I began to think,” she wrote in 1999, and she explained in one of her autobiographical novels that she chose the English language as “the rope to save me from drifting awash in the fluidities of multilingualism.” As addiction destroyed her mother, friends helped and sheltered her in ways that, she later said, “allowed me space enough to learn to write.” It was to be a long apprenticeship. She wrote complete drafts of a couple of novels during the 1930s, but they were never published, and she herself later dismissed them as “bad and derivative.”

In 1933, while living in France with an American painter named Eva Herrmann, Bedford criticized Germany’s Nazi regime in a book review. Berlin took note of her mother’s ancestry, which was part Jewish, and froze the assets she had inherited from her father. The only passport she held was German and due to expire soon. “We must get one of our bugger friends to marry Sybille,” Maria Huxley declared, and in 1935, Sybille became a British citizen by marrying a friend’s butler’s ex-boyfriend. (According to the groom, Bedford had been his mother’s name.) At the reception, showgirls, rough trade, and Virginia Woolf rubbed shoulders.

Bedford sailed for America in 1940, and in New York she was given the job of driving Thomas Mann’s poodle to California. She had love affairs, first with Cyril Connolly’s sister-in-law and then with Esther Murphy, a voracious reader and great talker who was working on a biography of Madame de Pompadour. “Her head looked a little like Thomas Jefferson’s, though her general build made one think more of Don Quixote,” Bedford was to recall. Unfortunately, Murphy’s talking came at the expense of her writing, and she did more than a little drinking as well. “I thought I could make her work,” Bedford told Lisa Cohen, who profiled Murphy in her thoughtful and lively group biography All We Know. No book by Murphy was ever to see the light of day.

Murphy became an inspiration for Bedford’s first book, however. In 1946, while the two women were traveling together in Mexico, Murphy’s notes on Madame de Pompadour were stolen, and Bedford lost the manuscript of a cookbook she was writing. One night on the shores of Lake Chapala, where they were the guests of a munificent, bankrupt Mexican gentleman, it occurred to Bedford to write about the journey itself — to combine the story of her, Murphy, and their host with tales of Mexico’s past, which the history-minded Murphy was no doubt encouraging her to explore.

Bedford wandered between Italy and France for half a decade while writing A Visit to Don Otavio, abetted by a stipend from a generous friend of modest means and impeded by mysterious eye trouble and by a distracting and, in Cohen’s word, “algebraic” romantic entanglement involving four other women. Though Bedford had conceived of the book as tragic, she felt that it came out comic. Murphy, identified only as “E,” was an unlikely tourist, and Bedford enjoyed sending up her spiritual and corporeal inflexibility: “ ‘I will not go to this volcano,’ said E, in the manner of Edmund Burke addressing the House of Commons.”

Still, because Bedford saw the country’s poverty and violence, and because she was curious about the political history behind them, there is a sustained note of melancholy. While on her own in London as a teenager, she had seen one of the surviving fragments of Manet’s The Execution of Maximilian at the Tate, and the painting had stuck in her mind, perhaps on account of the emperor’s name, which was the same as her father’s. In Mexico, the painting came to life for her. An archduke in the Hapsburg family, Maximilian was sent to Mexico in 1864 by the French dictator Napoleon III to serve as a figurehead while France squeezed the country for unpaid debts. Told that the people of Mexico had voted for him, he was naïve enough to believe it. It didn’t occur to him that for someone like Napoleon III, political ideals were no more than a cover for brutality. Maximilian, Bedford quipped, might under different circumstances “have made an excellent officer in the Salvation Army.”

History had played a trick on him, as it had on her father. It had done the same to her host on Lake Chapala, whom she called Don Otavio — another gentle man struggling with how to live on in the ruins, architectural and emotional, of his family’s glory, and another father figure for Bedford. Her portrait of him is heartbreaking:

A youngish man stood on the terrace of a very ugly house. He ran out to meet us. He was wearing white flannels and a charming shirt decorated with sea horses. A bunch of gold holy medals tinkled in the open neck. His hands and complexion were white as asses’ milk; his face, a long oval with slightly softened contours crested by a plume of silvery hair, was a generic face: one of those inherited handsome faces of Goya’s minor courtiers, where the acumen, pride and will of an earlier mould have run to fatuity and craft; a set face, narrow, stiff and sad. He turned out one of the kindest men I ever met.

In the evenings on Lake Chapala, Bedford played piquet with Don Otavio, as she had once played roulette with her father — careful not to lose, lest he have to accept her money and she thereby wound his pride.

In 1952, exhilarated that her manuscript about Mexico had been accepted for publication — she was at last the writer she had long claimed to be — Bedford began a new novel, her first attempt in over a decade. She was forty-one. The wife of a Fulbright scholar had fallen in love with her, and the two women were living together on a rooftop that had been one of the sets for Rossellini’s Rome, Open City. This time Bedford wrote about her father more or less in his own person, giving him the name Julius Maria von Felden — le beau Jules. Her approach was not through her own experience of him, however, but through stories she had heard about his childhood and about his courtships of his first wife and of Bedford’s mother. Bedford did draw on her personal memories to describe the parents of her father’s first wife. Their ugly Berlin house — “The walls were chocolate-brown, embossed; the upholstery magenta” — was one of the few pieces of stable ground in her shifting childhood, and she lovingly catalogued the limitations of the people she had thought of as her grandparents: “No music was heard. . . . They never travelled. . . . They took no exercise . . . they kept no animals. . . . They did not go to shops. . . . They never read.”

In A Legacy, Bedford puts her intellect at the service of the reader’s pleasure in remarkable ways. She is able to condense into an apercu, for example, the intricate relationship between a person’s way of perceiving and the moment in history he happens to inhabit, writing of Julius and his humane but old-fogyish father and brothers that “the French Revolution was still alive with them as a calamity, and of the Industrial one they were not aware.” The spareness and edge of her dialogue inspire such close attention in the reader that even a non sequitur becomes telling. “No, not that pear,” Julius suddenly insists, in the middle of a conversation about antique collecting with the woman who will become his first wife. “Let me choose one for you.” Intellect, in the world of Bedford’s novel, is not at war with appetite; it deepens appetite, by making appreciation more knowledgeable and precise. Of a luncheon that Julius serves while wooing, Bedford writes:

The sea-urchins came heaped in a great armorial pile, sable and violet, tiered on their burnished quills, like the unexplained detail on the hill by the thistles and the hermitage of a quattrocento background.

Again and again, the reader has the impression that a potentially overwhelming sensory experience has been sifted by a connoisseur on one’s behalf — has been rendered almost weightless. Reading A Legacy feels like going to a fine restaurant with someone who knows how to order. Like having the right pear picked out for one.

When A Legacy was published, Evelyn Waugh described it in The Spectator as “a book of entirely delicious quality.” He was thrown, however, by Bedford’s canny understanding of the law and the press, which she had acquired during her teenage afternoons in English courtrooms, and he wrote to Nancy Mitford that the name Sybille Bedford had to be the pseudonym of “a cosmopolitan military man, plainly, with a knowledge of parliamentary government and popular journalism.” Indeed, from the 1950s to the 1970s, while living in England, Italy, and France, Bedford worked as a court reporter for Esquire, Life, and Vogue, showing off her ear for dialogue and talent for précis while covering the trials of the English publisher of Lady Chatterley’s Lover and twenty-two guards, bureaucrats, and medical personnel at Auschwitz.

Bedford wrote two books about the law. In The Best We Can Do (1958), she recounts the trial of John Bodkin Adams, a doctor accused of murdering an elderly patient with heroin and morphine. At the time, most journalists took it for granted that Adams was guilty; it was rumored that there were many more victims, and even today he is tagged on the Internet as a serial killer. Bedford was immune to the hysteria, perhaps because morphine was no novelty to someone who had bought it for her mother in waterfront bars. She chose to report the trial “solely from the point of view of an alert spectator,” as she put it, limiting herself to what a member of the jury would have seen and heard, plus a little of the press banter. Examined by this method, Adams didn’t appear quite so sinister. The prosecution tried to prove that his doses of opiates were unusual and unusually high, and were administered while the patient was “semi-conscious.” In fact, the defense pointed out, it was another doctor who started the patient on morphine. The defense also succeeded in getting two of the prosecution’s medical witnesses to admit that they knew of similar cases that had received similar treatments. The nurses’ logbooks, moreover, showed that the patient had been feisty almost until the end, deriding one of them as “a slum woman and a brute” and, on her last day, eating a meal of partridge, celery, and pudding with brandy and soda. While his patient’s death was being investigated, Adams had said to a detective, “Easing the passing of a dying person is not all that wicked.” Was this a murderer’s confession, or an argument for end-of-life care? The jury found Adams not guilty.

For The Faces of Justice (1961), Bedford toured courts in England, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and France, and wrote about what she saw — a simple plan that enabled her to make surprisingly powerful comparisons. The law, Bedford writes, “is an essential element in a country’s life. It runs through everything; it is part of the pattern, like the architecture and the art and the look of the cultivated countryside.” In Germany, during a homicide trial, the whole court — judges, jurors, lawyers, even the defendant — takes a field trip to the scene of the crime and reenacts the killing, with a law student playing the part of the victim. In France, a man who calls a policeman a bastard is fined 20,000 francs. A Swiss clerk is so proud of his canton’s judicial system that an opportunity to show it off makes him “as happy as a man taking a boy to his first circus.” Bedford is such a deft reporter that she is able to capture both what a witness says (“and suddenly he put a revolver on the counter, it was covered with a handkerchief, a silk handkerchief, but I could see the muzzle, I hardly believed my eyes”) and a transcribing clerk’s neatened, slightly falsified version: “He suddenly put a revolver on the counter, a handkerchief was placed over it.”

Bedford intended for her next novel, A Favourite of the Gods (1963), to have “almost no autobiographical sources or associations,” but she didn’t quite manage it. The novel is about two women: a mother who becomes miserable when she discovers that her Italian husband has cheated on her, and a daughter who is by inclination and according to principle a rake, and therefore happier. Both women are attractive; both have more intellectual firepower than they know what to do with. In other words, both seem to be portraits of Bedford’s mother — the rake that she was in youth and the scold that she became in middle age — though the daughter channels Bedford herself when she asks her mother, “How can you be so unforgiving?”

The novel never really gets started; the philosophically promiscuous daughter never feels any one passion strongly enough to fight for it. As if Bedford sensed the flaw and was at a loss for how to repair it, she told the story a second time in the novel that followed, A Compass Error (1968) — a strange, unforced doubling of her error. But then, fortunately, A Compass Error turns into a neat little Jamesian thriller. Flavia, the seventeen-year-old daughter of the daughter in A Favourite of the Gods, is living on her own in a French seaside town in the 1930s, an aspiring writer eager to explore her awakening sexuality. The morning after bedding a neighbor’s wife, she looks up from a volume of Gibbon and giggles, “The sensual life is in the bag,” confident that the faith in reason that inspired that eighteenth-century historian will guide her through the shoals of eros in the twentieth. If only lust could be rationalized so cozily. Flavia soon falls for a cynical beauty — a version, Bedford later admitted, of the woman she herself had fallen for as a teenager — who sneers, “Physical passion is not as deliciously dix-huitième as you like to think it is,” and proceeds to prove the point.

A two-volume biography of Aldous Huxley followed, published in 1973 and 1974. In 1976, Bedford’s partner of twenty years, an American novelist named Eda Lord, died of cancer, ending a relationship that had become a burden on account of what Bedford called Lord’s “defeatism.” Left to her own devices, Bedford decided to return to autobiographical fiction. She hadn’t yet written about living with her father when she was a child, and she hadn’t touched the darker aspects of her mother’s story at all. It took a decade for Bedford to overcome her inner censor, but at last, in 1989, she published Jigsaw, subtitling it A Biographical Novel.

The texture is rich and mellow. Although Bedford unweaves a number of the fictions that she had imposed on her readers in A Legacy, the mood is not one of disenchantment but of ripeness: she’s strong enough for the truth now, and the time has come to tell it. She writes about napping in a pram while her mother has a tryst, about running away from her impoverished father, and about causing talk in her village by playing with the boys instead of the girls. She writes about how cruel her mother was when she learned that Bedford had fallen for a woman — “Don’t go about thinking of yourself as a doomed Baudelairean pervert” — and about how lost in morphine Lisa eventually became, secretly pawning a gold cigarette case given to Bedford by her father and taunting her daughter as a coward when she declined to try an ampoule herself. But by then the writer had learned that reason could not always be pleasure’s friend. In a lucid moment, after quizzing Bedford about a novel that she was trying to write concerning a fictional young man, her mother said, “You have me. I’m a much more interesting subject.” Indeed, she and le beau Max were Bedford’s greatest characters.