A naked man grabs me by the lapels and bares his teeth in frustration. I say naked, when I mean clad in a skintight nude suit that delineates his six-pack and decorously abstracts his genitals in the manner of a kids’ action figure. I have been assaulted by the personification of Anger. I’m probably being paranoid, but the unshakable sense of foreboding this gives me derives, as far as I can tell, from the suspicion that his little coup de théâtre is so effective because the guy playing Anger has actually taken against me, can discern in me something weak or sinful that he could exploit as grist for his performance. Earlier, a jester wearing a boat around his midriff had sniggered at the way I was holding my press folder. Maybe I’m not being paranoid, and the bad feeling I’ve had since I walked onstage at the Theater aan de Parade — which will increase over the course of my stay — is only an appropriate response.

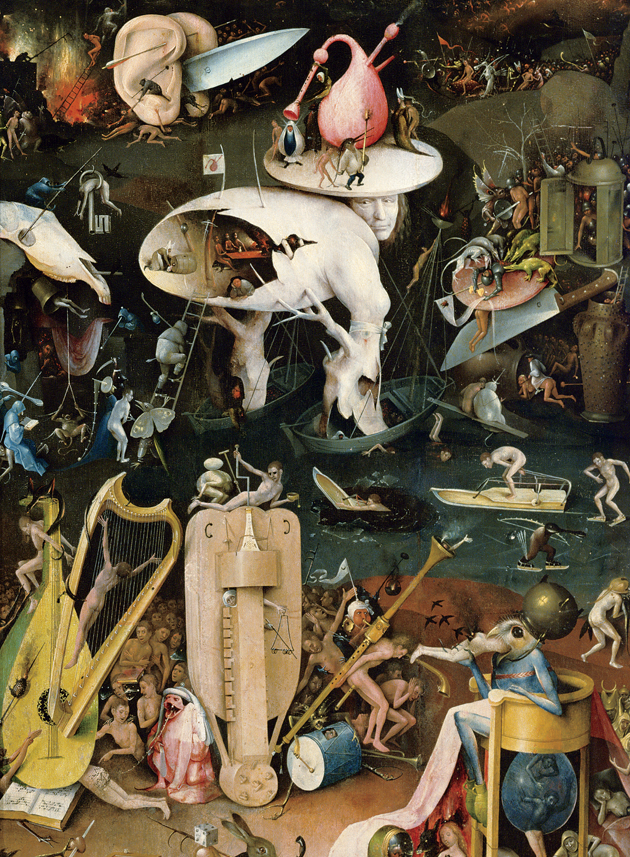

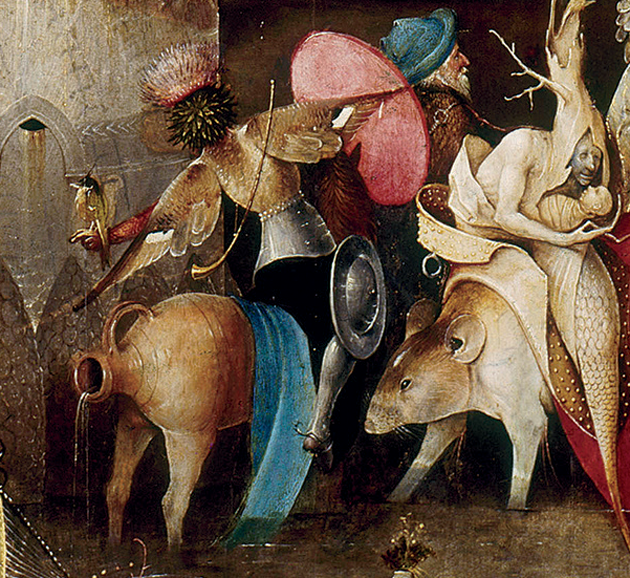

Detail of the right panel, depicting Hell, of 1490–1500 © Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid/Bridgeman Images. All artwork, unless otherwise noted, by Hieronymus Bosch

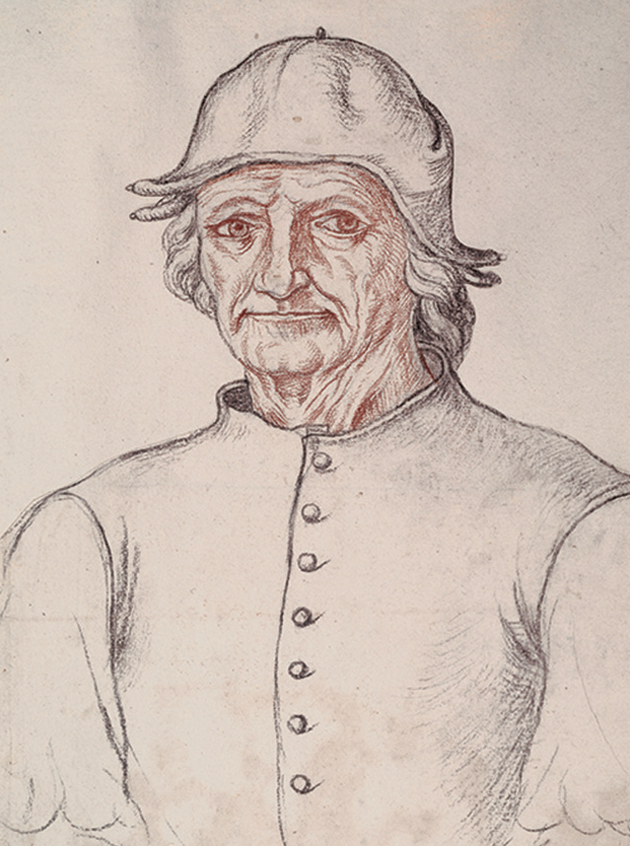

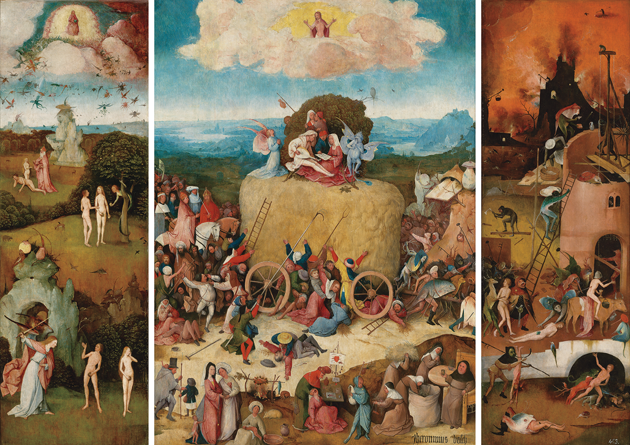

Hieronymus B., Nanine Linning’s immersive “dance triptych,” is one of more than ninety “fascinating cultural experiences” to be staged in and around the small Dutch city of ’s Hertogenbosch to mark 500 years since the death of its most famous son. No one knows exactly when Jeroen van Aken was born, but the date of his funeral mass at St. John’s Cathedral — August 9, 1516 — is recorded in the archives of the Brotherhood of Our Lady, the then-Catholic confraternity that counted him among its members and in its ecumenical incarnation survives to this day. (“Hieronymus,” incidentally, is a Latinization of “Jeroen,” or “Jerome,” Bosch’s patron saint and later a favorite subject; in adopting the name of his hometown, Bosch was swapping one toponym for another — Aachen, in Germany, being the birthplace of his ancestors.) From a contract dated to 1475, which mentions Bosch working with his father on a carved altar for the brotherhood, it’s assumed he was born around 1450.

’S Hertogenbosch lies roughly fifty miles from Amsterdam, in the southerly province of North Brabant. It’s a quiet, attractive, prosperous-seeming place, with a well-preserved medieval center inside the remains of its fourteenth-century ramparts. On the train from Schiphol Airport the announcer placed heavy emphasis on the first syllables, ’S-HER-to-gen-bosch, as if to gee himself up for the syllables to come. The locals give themselves a break and call it Den Bosch. The focus of the celebrations is Visions of Genius, an exhibition of Bosch’s work at the Noordbrabants Museum (which ended on May 8); Charles de Mooij, the director, has secured seventeen of the surviving twenty-four paintings attributed (with varying degrees of certainty) to Bosch, and nineteen of the surviving twenty works on paper. Never before — conceivably not even in his lifetime — have so many of Bosch’s works been assembled in one place, all the more impressive an achievement given that the Noordbrabants is a small, provincial museum, numbering precisely zero Bosches in its permanent collection.

The quid for the Noordbrabants’s quo, in the case of the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice and other world-class institutions loaning work to the exhibition, comes in two forms: restoration and knowledge. With backing from the government, corporate partners, and the Getty Foundation, the Bosch Research and Conservation Project has restored nine of the loans and undertaken detailed reflectographic analysis, resulting, among other things, in the attribution to Bosch of two pieces hitherto considered to be workshop: a drawing, Infernal Landscape, and a panel fragment, The Temptation of St. Anthony, the latter stored for the past decade in the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City, Missouri.

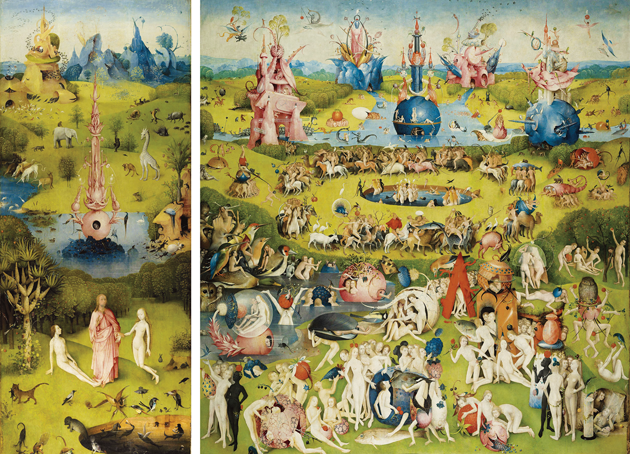

The left and center panels, depicting Eden and a false Paradise, of The Garden of Earthly Delights. Courtesy Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

There’s a deal of national and civic pride at stake here. The official slogan of Jheronimus Bosch 500, printed on banners fluttering from the city’s lampposts and on the blue track tops sported by its crack detail of official guides, is welkom thuis, jheronimus! — “Welcome home, Hieronymus!” (If it grates that Bosch’s most famous painting, The Garden of Earthly Delights, is staying put in the Prado, none of the infallibly charming and diplomatic representatives of JB500 will admit it. The Spanish are oddly proprietary about the painter they refer to as El Bosco, perhaps because gruesome depictions of Hell remained popular in ultra-Catholic Spain long after they had lost their appeal in Northern Europe. When I ask Lian Duif, JB500’s director, if a loan of The Garden was ever in the cards, she is categorical. “We didn’t even ask for it,” she says. “It’s the same as our Night Watch — it will never travel.” The objection that Rembrandt was Dutch, and Bosch not Spanish, seems abruptly inappropriate, and I take a big bite of my complementary apple pancake to cover the silence.) The program of ancillary events — the “Bosch Experience” — seems designed to reassert a link weakened by half a millennium of acquisition and dispersal, and to carry on reasserting it long after the Noordbrabants show completes its short run. (Until September 11, the paintings will be reunited with Earthly Delights at the Prado, in a show that the Spanish, true to form, are calling “the most complete and one of the highest quality organized to date.” Bienvenido a casa, Jerónimo.)

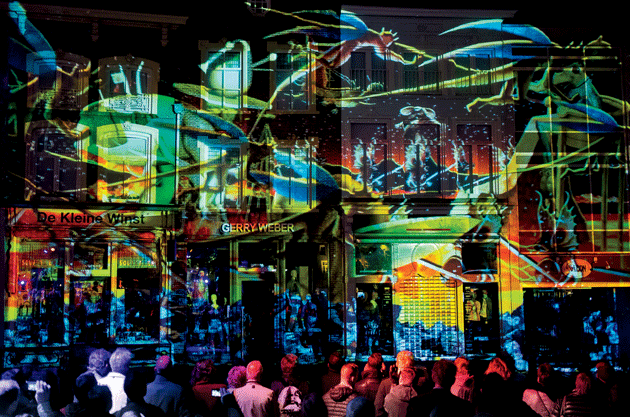

Aside from Hieronymus B., visitors to Den Bosch in 2016 are promised a Heaven and Hell cruise, by open boat along the canalized River Binnendieze, which runs through and sometimes underneath the city center and will in certain subterranean stretches be enhanced with 3-D projections of hellfire, screeching bats, and winged demons; A Wondrous Climb, a walk up a clanging gantry staircase to the roof of St. John’s Cathedral, for a look at both the grotesques on the flying buttresses and, beyond the city limits, a sodden polder called the Bossche Broek, supposedly much as it was in Bosch’s time; and Bosch by Night, the obligatory son et lumière, in which animated figures from Bosch’s paintings will be projected against the facades of four buildings on Markt, the town’s main square.

Many of the events depend, like Hieronymus B., on the animation of Bosch’s imagery. (Albinus in Nabokov’s Laughter in the Dark has pretty much the same idea, to have “some well-known picture, preferably of the Dutch School . . . brought to life.” But then, “his life ended in disaster.”) The implication, I guess, being that art is more accessible when it moves, and the still stuff is for a specialized audience prepared to fork out twenty-two euros to get past the security guards at the Noordbrabants. In any case, for the rest of the year the city will assume the status of an upmarket theme park based on the bold proposition that insistent and graphic reminders of the eternity of torment awaiting all but a few of us might represent a fun day out for all the family. The calculation seems to be that Bosch’s appeal has long extended beyond his natural constituency of museumgoers. I don’t know much about art, but I know I like men farting out blackbirds while being eaten alive by blue bird-headed monsters, shod in pewter jugs.

You can almost hear Ton Rombouts rubbing his hands. Rombouts, the mayor of Den Bosch, is smooth in a vaguely Blairite fashion, well-preserved for sixty-five, with the mobile middle of the practiced politician, accustomed to multilateral glad-handing. In his welcome to the press he trots with exemplary freshness through a speech he must have given a thousand times. The difficulty of pronouncing ’s Hertogenbosch. Its “Burgundic atmosphere.” (For a period in the fifteenth century, the Duchy of Brabant was ruled by the dukes of Burgundy, the legacy of which is, supposedly, the easygoing, café-cultural, work-to-live joie de vivre that marks the locals out from the sullen Calvinists north of the Maas.) The intolerability of leaving town without trying the local speciality, the Bossche bol, which, by all appearances, is nothing other than a massive profiterole.

The difference this year, of course, is Hieronymus, whose benefit to the city of his birth, Rombouts explains in his mostly fluent English, can be expressed not only in tourist “spendings,” welcome as they may be, but in terms of the lessons Bosch can teach us in this “time of fear,” when the seven deadly sins “are still worrisome topical.” By depicting them so vividly, Bosch can help us not capitulate to “hate and greed and fury.” If Rombouts has an overriding ambition for the Bosch 500 program, it’s that it will bring “hope, again, to our society.” It’s a notion I’ll hear promoted several times over my two visits: Bosch as the painter of hope.

In the absence of Earthly Delights, the star attraction at Visions of Genius is The Haywain. When I visit after the show has opened to the public, there are almost as many people crowded in front of the triptych as there are depicted in its famously populous central panel, which is kind of apt given what the painting has to say: we’re going to Hell. All of us. In hard-edged, high-keyed pinks and blues and yellows, all manner of humanity escort a wagon piled high with hay as it trundles, unbeknownst to them, toward damnation. As the art historian Walter S. Gibson notes, hay would have been familiar to early-sixteenth-century audiences as a metaphor both for the worthlessness of material goods and for deceit: “To ‘drive the haywain’ with someone,” he explains, “was to mock or cheat him.”

Thus the devil and his retinue entice us with the lie of worldly gain, grabbed at by the peasants and burghers in the foreground, who tussle over tufts of dried grass like bargain hunters on Black Friday. Bottom right, a fat friar sits guzzling ale as nuns stuff a sack with armfuls of hay purloined from the wagon. To the left, a pope (identified by some scholars as the libertine Alexander VI, object of Savonarola’s scorn), an emperor, and his courtiers follow on horseback, their conspicuous dignity ironized by their direction of travel. They’re all headed the same way. Above, ignored by everyone save an angel kneeling in prayer, a small and rather ineffectual Christ emerges from a pink-and-gold cloud, holding up his arms as if to say, “Uh, hello? Remember me?” The procession to Hell matches the drift of our interest: it’s no surprise to find the crowd that much thicker in front of the right panel. (In the left panel, the Expulsion from Eden, the Fall of Man, the Creation, and the Fall of the — horrible, insectoid — Rebel Angels are presented in vertical succession. Read against the left-to-right orientation of the central and right panels, the gist here seems to be that the Creation and Fall were as good as coeval, i.e., that Paradise was gone in the blink of an eye.)

You get the sense, talking to some Bosch aficionados, that liking him for his hellscapes and outlandish teratological imagination is a little non-U; what’s really interesting are his landscapes and depictions of the hermit saints. Whether you consider this good taste or contrarianism, there is evidence to suggest that Bosch’s popularity in the sixteenth century rested on his infernal scenes as much as it does today. “People like the dark stuff, they always have,” Richard Charlton-Jones, formerly senior director of old-master paintings at Sotheby’s, London, told me. “If all he’d ever done was pictures of Paradise, the demand would drop by half.” No one knows who commissioned The Haywain — or indeed most of the surviving works — but we can surmise, from an account written around 1560 by the Spanish humanist Felipe de Guevara, that Bosch was chiefly (and regrettably, in Guevara’s view) valued as an “inventor of monsters and chimeras.” At the foot of The Haywain’s right panel, a sinner’s bare legs protrude from the mouth of a fish-creature with stockinged human legs for fins: a palindrome made flesh. Above, a toad chews on a philanderer’s privates while another naked figure, looking back toward the central panel as if there’s been some mistake, is bundled off to his perdition by a bipedal deer and a fish-faced demon in a cowl and studded leather kilt. As Gibson points out, in terms of its complexity — and violence — the hellscape in The Haywain falls somewhere between the spare composition of The River to Hell panel, from the Palazzo Grimani in Venice, and the right-hand panels of The Garden of Earthly Delights and the Vienna Last Judgment.

Neither of these large-scale triptychs is on loan to the Noordbrabants, but fans of Bosch at his most fanciful may derive some satisfaction from the Heaven and Hell cruise, which features scaled-up, rigid-foam models of some of the more notable monsters, mounted on the banks or emerging from the river like unspeakable things revealed by the recession of floodwaters. The afternoon I go, the 3-D projections of airborne demons and swarming bats are still pending on account of the actual bats hibernating in the tunnels, whose alarm at their own replication, let alone the megawattage of doomy music, is likely to prove more fatal to them than ours is to us. So no projections. It’s a lovely, cloudless day, cold and clear as a new contact-lens prescription. From somewhere in a leafless tree a crow opens his throat in casual commentary. We drift past a pair of giant ears bisected by a six-foot carving knife. On the near side a black demon is dragging a naked sinner into the auditory canal. I think about screaming in horror, but it is too tranquil even to joke about the incongruity. A member of the boat party asks Hugo Groeneveld, our skipper and guide, why Bosch’s excoriation of religious figures hadn’t seen him tried for blasphemy. Groeneveld draws a comparison with the Danish cartoonists who controversially depicted the Prophet Mohammed in 2005.

“But Bosch did it in such a subtle way,” he says.

The Haywain, 1512–15. Courtesy Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, and the Bosch Research and Conservation Project

This does get a laugh, but not the one that Groeneveld intended. We are drifting past a four-foot figurine of a pig in a nun’s headdress. In Groeneveld’s defense, while the import of Bosch’s Hell scenes is anything but subtle, there is a delicacy in even his most fantastical figures, a minuteness of observation that intensifies their uncanniness by grounding it so firmly in reality. Reality duly reciprocates by seeming suddenly uncanny. (“At least some of the time,” Joan Didion admits in Slouching Towards Bethlehem, “the world appears to me as a painting by Hieronymus Bosch.”) There have, over the years, been a number of variably cockeyed attempts to prove that Bosch was a heretic, the weirdness of his imagery explicable only as a form of pictorial samizdat, a coded appeal to fellow members of his sect. In the 1940s, Wilhelm Fraenger, a German art historian, claimed that Bosch was an Adamite, a medieval adherent of free love, on the basis that the goings-on in the central panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights look like so much fun that they couldn’t possibly have any admonitory intent. More recently, Lynda Harris has argued that Bosch was a closet Cathar, ostensibly orthodox in his Catholicism but using his paintings to spread the gnostic heresy that earth was a literal Hell, presided over by Satan.

Detail from the center panel of Temptation of St. Anthony, c. 1500 © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, New York City

This is highly unlikely. Granted, so little is known about Bosch that it’s hard categorically to disprove any theory about his intentions — although per contra you might argue that this leaves him especially vulnerable to sophistry. In the Middle Ages, membership of the Brotherhood of Our Lady was largely reserved for the nobility, and it’s surely a mark of Bosch’s popularity — and acceptability to the establishment — that he should have been made a sworn brother when the social status of the artist idled somewhere around that of the skilled laborer.

More conceivable: that he was a Catholic, devout and observant and without a trace of dissent, even on the brink of the Reformation; that he was a respectable and well-connected figure in the community. (We know, for example, that he married well, to Aleid van de Meervenne, the daughter of a more prosperous family than the van Akens.) As Gibson notes, ’s Hertogenbosch in the early sixteenth century was home to a remarkable number of convents and monasteries. “By 1526, just ten years after Bosch’s death, one out of every nineteen persons in ’s Hertogenbosch belonged to a religious order, a much higher proportion than can be found in other Netherlandish cities at that time.” Many of these foundations competed with the local crafts guilds in the sale of textiles and other goods, and in the light of the ill feeling this caused, it’s possible to square Bosch’s scathing treatment of religious figures with an entirely orthodox submission to church doctrine. Corrupt monks were fair game.

What marked him out was not creed but temperament, and the talent to express it. It’s not wholly true to say that Bosch’s mutant iconography is unique, a conceptual isolate. Scholars point to the likely influence of medieval manuscript illuminators, filling their margins with improbable bestiaries. Gibson maintains that the tetchy-looking, spoon-billed demon in the Vienna Last Judgment, carrying a bow and the sinner it’s just shot suspended from a pole, is a variation on a common motif. Other monsters may have been visualizations of Dutch proverbs or folkloric tropes now lost to us. Where Bosch does break fresh ground, other than in integrating these grotesques into large-scale compositions, is in the clarity of execution and level of invention he brings to the task. The thistle-headed, half-avian falconer-demon in the Lisbon Temptation of St. Anthony, armored from the waist down and riding a four-legged earthenware pot, is typical in being a freakish amalgamation of everyday elements, acutely observed, like a mix-and-match flip-book of nature illustrations. Bosch takes an orthodox idea — that Hell represents the inversion of the God-given natural order — and develops it as an artist might, freely, not by the lights of a heretical agenda, or under the influence, as some have suggested, of the natural hallucinogen ergot. The “Tree-Man” in the Hell panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights — hollow tree trunks for legs, boats for feet, broken egg for a torso with a tavern scene going on inside it — is frightening precisely because of the deal it strikes between wild invention and the sad, instantly identifiable reality of the figure’s near-apologetic facial expression, aimed directly at us. We feel pity for a man with a pub in his guts. (See page 68.) Bosch is frequently funny, as in his tolling bell with human clappers in the Infernal Landscape drawing, but like other masters of the comic-metamorphic — Saul Steinberg, say — he is a moralist, and a baleful one at that, unwavering in his certainty that all hope is in vain, that none but the very most ascetic will be spared, that the rest of us are headed to Hell in a hay cart.

Detail from Infernal Landscape, date unknown. Courtesy Het Noordbrabants Museum, ’s Hertogenbosch, and the Bosch Research and Conservation Project

Five days before Bosch by Night is meant to start, one of the buildings to be used as a backdrop collapses. As in, utterly. At the time of writing, it’s still not clear why, but some superficial renovation work was taking place in the optician’s office that occupied the ground floor. Shortly after ten that night, the last construction worker left the building, which a neighboring shop’s CCTV shows collapsing at 10:52. It’s a Saturday night on the corner of Markt and Hinthamerstraat, a main drag full of shops and bars and restaurants. Amazingly, no one is hurt. There’s an unsubstantiated rumor going around that a guy was in the lighting rig at the time, running tests, and had just projected an image on the building when the facade fell off and the interior dissolved into rubble, which if true must have freaked said technician the hell out. Anyhow, it’s an astounding piece of bad luck for JB500. You might have thought, having spent nearly nine years preparing your festival, and six months creating your light show, the one thing to rely on would be the 400-year-old building you’re planning to use as a screen. It’s hard not to imagine Mayor Rombouts sitting in pressed pajamas on the edge of his bed, uncradled receiver purring beside him, numb to Mrs. Rombouts’s tender hand on his shoulder. My tourist spendings, he’s saying. My hopes for what Bosch can teach us in this time of fear. What have I done to deserve this?

Word is that it’s a jinx. Hieronymus making himself known. Next door to the collapsed building is the house where he lived as a child. It’s practically unharmed, the neighboring structure having sheared away cleanly, leaving the shared wall exposed but for some remnants of plasterboard. (I’m reminded of the bombed-out second-story bedroom in Billy Collins’s poem “Building with Its Face Blown Off,” its wallpaper “exposed to the lightly falling snow / as if the room had answered the explosion / wearing only its striped pyjamas.”) To the extent that any town in the Netherlands is still Christian, Den Bosch is notably Catholic, with a subsoil of Marian mystery under its briskly secular surface. At a press conference on the day Bosch by Night was due to open, Lian Duif, putting on a brave face, is delivering the happy news that the Bosch house is okay, when, precisely on the words “is still standing,” a waitress drops a coffee cup and a large stack of crockery goes crashing to the floor. A big laugh goes up, tinged with unmistakable unease. (It’s at this press conference, incidentally, that I finally get to try a Bossche bol. It is nothing other than a massive profiterole, which makes me wonder if other middling cities on the make might choose their own public-domain pastry to supersize and lay claim to, like the four-foot cream horn of Gary, Indiana.)

The initial plan is to erect a screen in front of the disaster site so the light show can go ahead — and, of course, so that the shame of the wreckage can be hidden from view. At a preview of the Bosch by Night projections, shown indoors on the evening of the canceled premiere, Mo Assem, one of the young animators behind the project, speaks of his team’s inconsolability. “It’s as if our painting is now missing, someone’s destroyed it.” Again, at the time of writing, no one is sure when the screen will go up, but in the meantime it’s tempting to view the pile of rubble it will eventually conceal as the Hell panel of a gargantuan triptych. (In the event, the show is shifted two facades to the right, avoiding Markt altogether.)

I leave the disaster site and return to the Noordbrabants. One of the triumphs of Visions of Genius is in reuniting the fragments of the Wayfarer triptych, which, since it was sawn into bits at some point in the eighteenth or nineteenth century, have been exhibited as separate paintings. Looking at The Ship of Fools, once part of the left-hand panel, it’s remarkable to recall that Bosch was an almost exact contemporary of Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519). A man is steering an overcrowded boat with an outsized wooden spoon, or would be if he weren’t more intent on biting into a spherical cake, suspended like an apple from a string. An old nun and a friar are singing along to the lascivious pleasing of a lute. A drunkard vomits over the bow under the watchful eye of an eerily diminutive jester, perched in the rigging and sipping from a cup.

Death and the Miser, c. 1485–90. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., and the Bosch Research and Conservation Project

As Paula Nuttall, an associate lecturer at the Courtauld Institute, pointed out when I met her, “Folly is equated with sin in this period. It’s not just, oh, you’re a bit stupid. Folly is bad.” Far from the humanist ideal established the other side of the Alps, Bosch’s Ship of Fools shares the late-medieval negativity of its namesake and possible source, Das Narrenschiff (1494), a verse satire by the German poet Sebastian Brant. Man is not the measure of all things but of lust, corruption, and drunkenness, Vitruvian Man bent over the handrail, losing his lunch. A similar defeatism might be read into the central panel of the Vienna Last Judgment. Compared with Rogier van der Weyden’s Beaune Altarpiece, painted at least thirty years earlier, the Judgment’s Christ and the chosen few entrants to heaven — twelve, to be precise — take up a tiny portion of a picture plane mostly given over to an earth indistinguishable from Hell. Righteousness is a fringe characteristic.

The case for Bosch as an exemplar of the Northern Renaissance — argued, without a great deal of evidence, by Waldemar Januszczak, in his recent BBC takedown of Giorgio Vasari — is further weakened by the artist’s technical peculiarities. Again, the comparison with his early Netherlandish forebears is instructive. A painting like The Descent from the Cross, across the way from The Garden of Earthly Delights in the Prado, shows Rogier van der Weyden building up tone through the meticulous layering of oil glazes, creating, as Nuttall puts it, “this wonderful, glowing, jewel-like perfection” and colors that are “almost porcelain-smooth.” The thinness of Bosch’s painting, by contrast, is evident in the former right-hand panel of the Wayfarer triptych, known as Death and the Miser, wherein traces of underdrawing are clearly visible. At some point between preparation and painting Bosch has evidently decided that the bag of money in the dying miser’s hand would be better proffered by the nasty little demon at his bedside — rendering, incidentally, the composition marginally more optimistic. In that millimetric shift Bosch has given the miser one last chance to repent.

The emphasis, in much of Bosch’s work, is on compositional intricacy, “the same urge for universality,” in Gibson’s phrase, “that we encounter in the facade sculptures of a Gothic cathedral,” as opposed to the elevation of the individual to godlike gorgeousness. That said, for all that his eschatological gloom and decorative, unsculptural figuration locate Bosch firmly in the Middle Ages, there are elements in his painting that prefigure later periods. Gibson claims that the “iconographical programme” of The Garden of Earthly Delights — the giant birds, the profusion of fruit, the guy with a posy of flowers shoved up his backside — plays to the “Renaissance taste for highly original . . . allegories whose full meaning is apparent only to a limited audience.” (Others might argue that elaborate pictorial cryptography is a defining characteristic of medieval art.)

Some of Bosch’s backgrounds anticipate subsequent advances in landscape painting. Richard Charlton-Jones considers Bosch’s landscapes “the most original and overlooked” element in his work. Landscape painting would not become an independent genre until later in the sixteenth century; had it existed earlier, Paula Nuttall believes, Bosch might well have been considered a pioneer. “If you just zoomed in on his landscape backgrounds and clipped them into a PowerPoint,” she told me, “you could probably persuade your audience that they were looking at something much later.”

Closed, the wings of the Wayfarer triptych would have revealed the eponymous tondo, now a stand-alone panel loaned by the Boijmans van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam. Our ragged protagonist, possibly corresponding to Elckerlijc, a Dutch counterpart of Everyman, turns to look at the tavern he has just passed, a dilapidated fleapit with the “secret, bestial” air of Jan van Hogspeuw’s watering hole in Philip Larkin’s “The Card-Players.” A couple canoodle in the doorway as a hunched figure voids his bladder against the outside wall. A cur snaps at the wayfarer’s heels. Above, in a tree, an owl — a figure for evil, not wisdom, and recurrent in Bosch’s paintings — aims a hungry gaze at a blue tit on a lower branch. (In St. Jerome at Prayer, on loan from the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent, recent restoration has disclosed a second, smaller owl lurking in a rocky niche nearby. “Little owl is looking at the big owl, and the big owl is looking at you,” explains Ron Spronk, a technical art historian and member of the Bosch Research Project. “It’s an indirect owl.” That is, big owl has got your number, and little owl has his: a mise en abyme of highly prejudicial surveillance that doesn’t do my fragile self-composure any favors at all.) We are in no doubt as to where the wayfarer’s path will lead him, but the presiding mood of despair is lifted, or at least leavened, by the tenderness of the landscape in the background, rendered in hazy grays and yellow-green. We are transported even as we are warned; it’s one of the loveliest passages of painting in the exhibition, as subdued and contemplative as a Morandi.

Detail from St. Jerome at Prayer, c. 1500. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent, Belgium, and the Bosch Research and Conservation Project

In heavy rain I leave the museum and walk through Markt on my way to the station. Brush and palette in hand, August Falise’s 1929 bronze statue of Bosch turns its back on the fenced-off disaster site, either in disgust or denying involvement. I have some time to kill, but in the rain the brightly lit shops on Hinthamerstraat — America Today (“The College Lifestyle Brand”), a sports-shoe store called the Athlete’s Foot, in seeming innocence — are especially depressing, and I retire to a bar on the altogether more gezellig Korenbrugstraat. (“Gezellig” is a supposedly untranslatable term that seems pretty straightforward to translate: it means “cozy, welcoming.”) Tapperij Het Veulen is the sort of traditional, dark-wood bruincafé where the beer tastes better for the visual impression that you’re submerged in it. Even the air looks brown. The place is empty but for a couple of silent men at one end of the bar. I buy a Jupiler and am presented with a bowl of monkey nuts whose shells I am instructed, I think, to throw on the floor, not leave on the table. So I sit there, exposed to myself, munching on nuts as a mess of pitted shell fragments grows around my feet, afflicted by the suspicion that I’ve misunderstood, that I’ve got things exactly the wrong way round, and some sort of punishment is coming.