Across the seven volumes of the Recherche, Proust mentions only one living artist by name — the fashion designer Mariano Fortuny. “Is it their historical character, or is it rather the fact that each one of them is unique,” Marcel wonders about Fortuny’s creations,

that gives them so special a significance that the pose of the woman who is wearing one while she waits for you to appear or while she talks to you assumes an exceptional importance, as though the costume had been the fruit of a long deliberation and your conversation was somehow detached from everyday life like a scene in a novel?

Marcel buys many presents for his captive lover, Albertine, but when she leaves she takes with her only the blue Fortuny cloak.

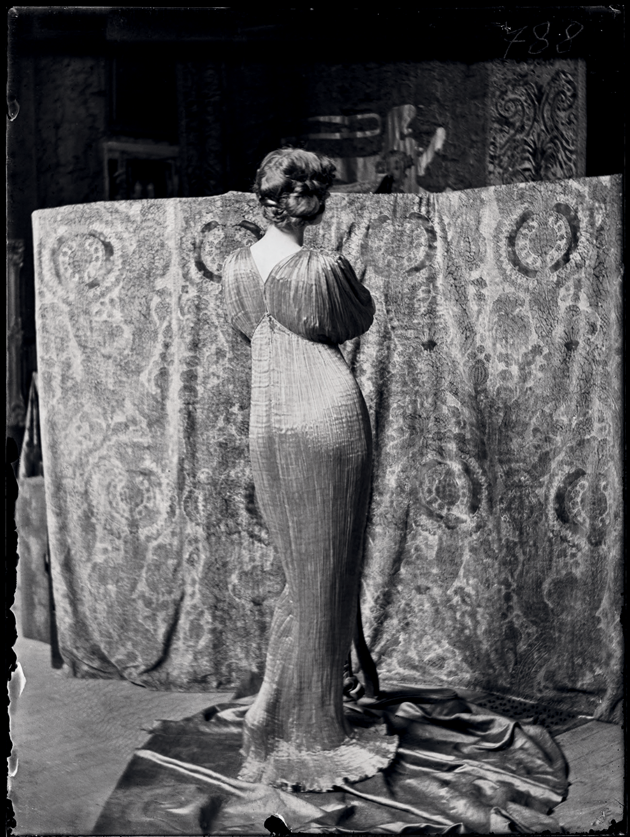

A model wearing a Delphos gown designed by Mariano Fortuny, c. 1920 © Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia/Archivio Museo Fortuny

Granadan by birth and Venetian by palazzo, Fortuny dressed royalty, nobility, and the likes of Eleanora Duse, Isadora Duncan, and Peggy Guggenheim. He specialized in unstructured, pleated, and often sheer gowns that were meant to be worn over a shift or, in the bedroom, nothing at all. They liberated women from the asphyxiation of whalebone, but their hemlines, which reached four to six inches in front of the toes, made perambulation a challenge. Susan Sontag, who in life always wore pants, found the perfect occasion for a Fortuny. She wore one to her funeral.

Fortuny appears as the lesser-known half of a patient, delighting, and penetrating book-length essay by A. S. Byatt, PEACOCK & VINE: ON WILLIAM MORRIS AND MARIANO FORTUNY (Knopf, $26.95). The English socialist and the cosmopolitan aristocrat were born forty years apart and had a little in common: both were craftsmen and inventors; both experimented with fabrics and vegetable dyes; both specialized in crowded but well-ordered patterns of birds, fruit, fronds, creepers, and acanthus; and both were “obsessive workers” who “made the place where they lived identical with the place where they worked.” What Morris and Fortuny really share, however, is that they both obsess Byatt.

Top to bottom: A woodblock print of William Morris’s Peacock and Dragon textile design, 1878 © GraphicaArtis/Bridgeman Images; design, in watercolor and pencil, for Morris’s Acanthus wallpaper, 1874 © V&A Images, London/Art Resource, New York City

She identifies intriguing points of connection, nodes that branch into enlightening contrasts, rather like Morris’s Peacock and Dragon pattern, whose swooping curves simultaneously hide and reveal the motions of its strutting, slithering creatures. Take, for example, the two artists’ shared interest in the Nibelungenlied, the medieval German epic on which Wagner’s Ring cycle is based. Fortuny — who also designed sets and lighting for the composer — made a brooding, deliriously romantic painting of Siegmund and Sieglinde clasped in each other’s arms, with a muscled Sieglinde wrapped in “agitated transparent veiling.” In his garden, Morris clipped Fafnir the dragon into a prim, orderly topiary.

That shrub still embellishes the grounds of Kelmscott Manor, the property that Morris leased with a friend, the Pre-Raphaelite painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Morris said he hoped for Kelmscott to be a retreat for his family, but, as Byatt puts it, “He was perhaps also trying to find somewhere where” the romance between Rossetti and Morris’s wife, Jane, “would be less visible.” The two had a long affair, and Rossetti made her the subject of fifty-seven studies, “always with the same large, red, hungry, mournful mouth.” Henry James recalled meeting the Morrises in 1868 — William reciting poetry in “his flowing antique numbers” and Jane, with her “Swinburnian eyes” and “great thick black oblique brows,” reclining on the sofa, “this dark silent medieval woman with her medieval toothache.” According to James, Rossetti’s portraits only seemed “strange and unreal” until you saw the woman in the flesh.

In their investigations of old and even ancient craft techniques, Fortuny and Morris were restlessly innovative. In addition to making bursting, sylvan wallpapers and textiles and writing novels, poems, and essays, Morris embroidered, created typefaces, and invented a special paper for his printing press. Fortuny, who was also a painter and photographer, took out more than fifty patents. For the theater, he invented a method of reflecting lighting that allowed him to “compose the setting onstage, conducting light as one conducts music.” (It is thanks to him that lighting artists sit in special booths.) He also designed furniture, lamps, a new kind of photographic paper, and tools; none of this, however, mitigated accusations that he was a copyist who stole patterns from religious garments and ancient Greek artifacts.

Peacock & Vine eschews argument for anecdote, lush description, and telling juxtaposition. Byatt quotes the scholar Peter Collier, for whom the issue of Fortuny’s originality is quite beside the point. As Collier puts it, Proust “sets his derivative dress-designer, Fortuny, at the apex of creativity,” making him, like the phoenix, an emblem for the recovery of time.

These Fortuny gowns, one of which I had seen Mme de Guermantes wearing, were those of which Elstir, when he told us about the magnificent garments of the women of Carpaccio’s and Titian’s day, had prophesied the imminent return, rising from their ashes, as magnificent as of old, for everything must return in time, as it is written beneath the vaults of St. Mark’s, and proclaimed, as they drink from the urns of marble and jasper of the Byzantine capitals, by the birds which symbolise at once death and resurrection.

Rebirth, like self-invention, is a privilege, and can be withheld by political forces. When Raden Saleh, the Javanese painter, returned to the Dutch East Indies in 1851 — after more than twenty years of hobnobbing with European royals whom he allowed to believe that he, too, was royalty — he shrank from the necessity of appearing at the Dutch colonial court in “native costume.” He wrote to King Willem III of the Netherlands for a dispensation, suggesting that instead of going shirtless in a sarong, he might wear a Western uniform, as the Javanese officers of the Dutch army did. Specifically, Raden Saleh asked to be allowed to wear a “fantasy uniform,” the garb of the Batavian civil-defense cavalry, “which is worn neither by the Dutch nor by the Dutch Indian military.” Besides, he added, if he were to appear in the local garb, how could he wear the decoration that Willem had awarded him, the medal of a knight of the Oak Crown?

As Jamie James notes in THE GLAMOUR OF STRANGENESS: ARTISTS AND THE LAST AGE OF THE EXOTIC (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $27) a “fantasy uniform” is a potent metaphor not only for Raden Saleh’s fantasy identity but for the insupportable position of the “educated native” under a colonial regime. I am grateful to James, without whom I would never have learned the story of Raden Saleh’s life — a life that also has the contours of a fantasy. One of six “exotes,” James’s grand word for exotic-seeking expats across the late nineteenth and the twentieth century, Raden Saleh studied orientalist painting in the Netherlands and brought it to Saxony, where it failed to catch fire. More influential was his importation of modern European art, or at least a European sense of aesthetic detachment, to Java. His 1863 canvas Drinking Tiger subordinates the animal to “the primordial majesty of the land”; it was the first painting by a Javanese artist to make the forest its main subject. “In the context of Javanese art,” James writes, “Drinking Tiger is as revolutionary as Olympia.”

James’s other main characters are white artists, musicians, and writers who fled an arid, suffocating Europe for the dream of an honest, immediate, sensuous life in Tahiti, Indonesia, China, North Africa, or Haiti. They all lived colorful lives — and all came to colorful ends:

Paul Gauguin died at fifty-four of tertiary syphilis, crippled by bleeding chancres and almost blind; Raden Saleh died of a broken heart after he was insulted and abused by the government in his native land; Walter Spies drowned within sight of land, locked in a cage aboard a sinking ship; Victor Segalen, forty-one, died in a freakish walking accident at a time when he felt life slowly abandoning him; Isabelle Eberhardt died in a flash flood in the Sahara.

His last figure, Maya Deren, the experimental filmmaker and voodoo adherent, died of a brain hemorrhage at forty-four. James suggests a poor diet and amphetamine use as the causes, but those of Deren’s friends who saw her possessed, including Stan Brakhage, believed that she had been put under a curse. (Her lover Teiji Ito, who was eighteen years her junior — Deren met him in a Greenwich Village movie theater when he was a teenage runaway — thought that she died “of anger.”)

The Glamour of Strangeness contains wonderful episodes and a memorable cast, and James’s reminder that colonial encounters sometimes involved amicable and eager exchange, and not merely force and exploitation, is well taken. But the book is marred by needless, showy digressions and unwelcome authorial intrusions. The writing is bloated with infelicitous imagery — “The record of Raden Saleh’s early life is spotted with lacunae, like the pages of an old book in the tropics tenanted by bookworms” — and James’s repeated description of homosexuality as “Greek games” is first cute, then grating.

Drinking Tiger, by Raden Saleh © State Palace of the Republic of Indonesia. Courtesy Susanne Erhards

In his desire to recuperate the complexities of expatriation, James takes tedious jabs at feminist and postcolonialist critics who have questioned the power dynamics involved in, for example, Gauguin abandoning his wife and taking pubescent lovers; that James is an American expat who settled in Indonesia explains his investment in the subject, but it makes the book feel less intimate than defensive. He argues, with some persuasiveness, that his exotes should be considered visionary, even great, artists and not simply interesting adventurers. Walter Spies, he writes, is not famous because he didn’t want to be; Victor Segalen’s Réne Leys is a “pioneering work” of modernism on par with The Castle. “Don’t they know,” he quotes Borges as saying, “that in Victor Segalen they have one of the most intelligent writers of our age, perhaps the only one to have made a fresh synthesis of Western and Eastern aesthetics and philosophy?”

An indisputable, though often overlooked, pioneer of modernism is Alfred Döblin, the German writer and neurologist best known for the novel Berlin Alexanderplatz. As Günter Grass said ten years after Döblin’s death,

The word “Kafkaesque” escapes our lips the moment we run into any bureaucratic difficulty. Our Brechtomaniacs can be easily recognized by their German-word-compounding-inclinations. Only Alfred Döblin occasions no conferences, rarely tempts our industrious literature professors into exegesis, seduces few readers.

The situation has improved a bit — more people know Döblin, if only from Fassbinder’s harrowing fifteen-hour adaptation of Berlin Alexanderplatz. Yet remarkably, BRIGHT MAGIC: STORIES (NYRB Classics, $15.95), translated by Damion Searls, is the first publication of Döblin’s short fiction in English. Perhaps we can now make “Döblinesque” happen. The collection’s early work is marked by a deranged psychological perspectivism, hairpin plots motivated by passion and sadism, and an abundance of murders and suicides. In the later stories, however, we find a curious, gentle whimsy, a predilection for the humorously fabular or the folkloric, and a passionate interest in the inner lives of animals. And always a courtship of the absurd, and language that is as vivid as Technicolor and as jarring as a car crash.

My favorite story in Bright Magic is “The Other Man.” It begins when a Boston gynecologist named Dr. Converdon hires a blond secretary named Mery, who has “beautiful braids.” He sleeps with her and discovers, to his dismay, that she is a virgin. Converdon’s behavior becomes erratic and brutal. He forces Mery to dance in a cabaret so that other men can ogle her; Mery enjoys the performance, but he doesn’t allow her to do it again — instead, he marries her. Shortly thereafter, Converdon receives a letter from an acrobat named Wheatstren, declaring his love for Mery and advising Converdon to save everyone a lot of hassle by killing himself. After considering the matter, Converdon consents. Wheatstren tires of Mery and pimps her out at the racecourse and the theater. This is the last line: “She, however, praised him at every turn, because he offered her the greatest thing that there is on earth: considerable variety.” It’s a love story.

Döblin is a true master — a scientist and a mystic whose characters, battered by a senseless world, cling to what today we would call existence or integrity but what he would have called the soul. They are alternately crude and fragile, suckers and saints. They hope and dream in excess of reason but are tethered to solid ground. In the very funny “Traffic with the Beyond,” a society of spiritualists is duped by a murderer. The fable “Materialism,” written after the author’s conversion to Catholicism, tracks the havoc unleashed when nature, including bulls, the grass, and water, learns of the primacy of matter. “Everything we do is meaningless,” thinks the tiger. “How could I have been so blind. It’s chemical reactions and reflexes wherever you look. . . . I started a family and brought seven rascals into the world for this. It’s sobering. A waste of time.”

If the tigers can’t go on, how can we? I am reminded of the prologue of Berlin Alexanderplatz, in which Döblin writes, in characteristic jagged shards, that his hero’s life will be given “this awful thing . . . meaning.” In Bright Magic, especially in the early dark stories, lives acquire meaning in the grimmest way, by flailing toward death. In “The Sailing Trip,” a woman returns to the scene of a fatality to drown herself. In “The Canoness and Death,” an old maid becomes aware of her impending demise; eventually Death jumps into her bed and drags her out the window. In “The Murder of a Buttercup,” a man cuts down flowers on a hillside, crazily atones for his offense, and goes out again, wielding his black walking stick like a scythe. There is no phoenix in the landscape, and nothing rises from the ashes.