Discussed in this essay:

Short Flights: Thirty-two Modern Writers Share Aphorisms of Insight, Inspiration, and Wit, edited by James Lough and Alex Stein. Schaffner Press. 236 pages. $16.95.

Last Aphorisms, by JPJ. Self-published. 88 pages. $9.95.

The World in a Phrase: A History of Aphorisms, by James Geary. Bloomsbury. 229 pages. $16.

The Oxford Book of Aphorisms, edited by John Gross. Oxford University Press. 394 pages. $27.95.

1.

I don’t read prose so much as root through it for sentences in need of rescue. At my most conceited and delusional, I imagine myself a literary scavenger, recovering sentences that might otherwise be lost in an excess of surrounding sentences. I’ve memorized three passages from Rosemary Edmonds’s translation of Anna Karenina, one about Anna’s son: “She had not had time to undo, and so carried back with her, the parcel of toys she had chosen so sadly and with so much love the day before”; one about Constantine’s brother: “Constantine saw that it simply was that life had become unbearable to his brother”; and one about Karenin’s frustration that it is impossible to speak to Anna both casually and tenderly: “He would involuntarily assume his usual bantering tone, which jeered at those who spoke like that [i.e., sincerely]. And in that tone it was impossible to say what needed to be said to her.” Anna Karenina has been reduced in my imagination to these three perfect passages.

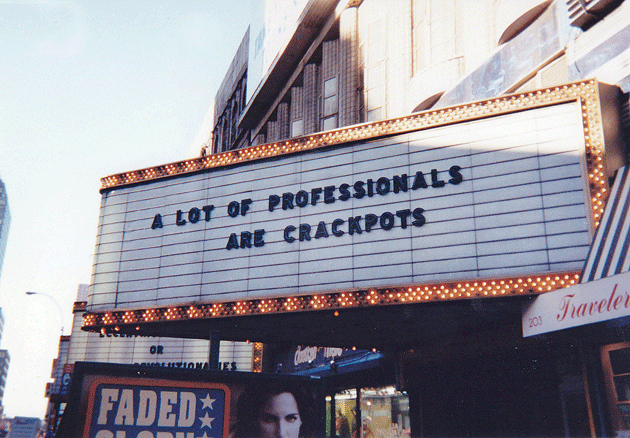

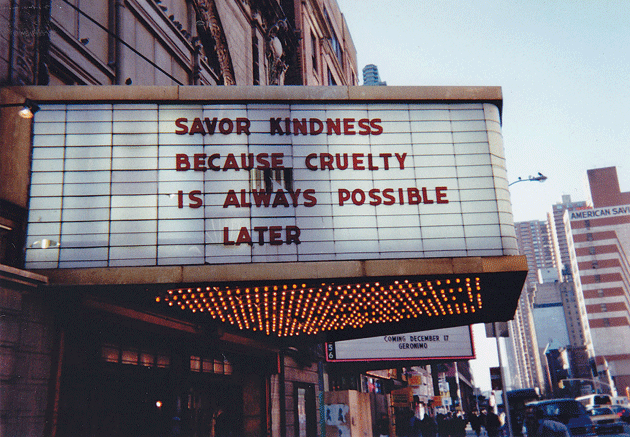

Forty-second Street Art Project, 1993, by Jenny Holzer © The artist/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City. Photographs by Don Shewey

2.

Some literary effects are possible only within the context of a durational reading experience. But I have a thing for writers who deliver their work by the line, the epigram, the apercu. These smallest of literary forms are variously judged as hubristic, timid, virtuosic, lazy, wise. Charles Baxter: “No one ever said that sonnets or haiku were evidence of short attention spans.” Pascal: “The present letter is very long, simply because I had no leisure to make it shorter.” Don Paterson: “The aphorism is a brief waste of time. The poem is a complete waste of time. The novel is a monumental waste of time.”

3.

The shortest pieces of writing strive not for greatness but perfection (per, “completely,” + facere, “make, do”), the utmost condition of madeness.

4.

I don’t necessarily abhor context, complexity, depth, qualification, specification, or volume per se; I simply abhor filler. But who am I to judge what’s filler? After the human genome was sequenced in 2000, it was determined that 98 percent of chromosomal material consisted of noncoding DNA, assumed to serve no function. Then, in 2012, several research groups discovered that so-called junk DNA actually contained genetic switches essential to the function of the organism; 80 percent of all chromosomal material was then believed by many scientists to be biochemically active. Two years later, after further studies, that amount was amended to 8.2 percent. Final judgment is pending.

5.

Hippocrates, the ancient Greek physician, coined the word “aphorism” in the fifth century b.c. to describe his collection of brief medical teachings. We think we know him by his well-handled “Ars longa, vita brevis.” But the whole aphorism goes like this: “Life is short, and Art long; the crisis fleeting; experience perilous, and decision difficult. The physician must not only be prepared to do what is right himself, but also to make the patient, the attendants, and externals cooperate.” His second aphorism begins: “In disorders of the bowels and vomitings, occurring spontaneously, if the matters purged be such as ought to be purged, they do good, and are well borne; but if not, the contrary.” In his several hundred aphorisms, Hippocrates writes much more about purging than he does about art. Here are two others I like: “Persons disposed to jaundice are not very subject to flatulence.” “Eunuchs do not take the gout, nor become bald.”

6.

John Gross, in his introduction to the Oxford Book of Aphorisms, notes that Hippocrates’ term took on a moral and philosophical tinge only after the Renaissance. By the seventeenth century, the definition had grown to include witticisms. Pascal called his Thoughts; Rochefoucauld called his Maxims. Even today no one seems to know just what to call them.

7.

Nor is there an agreed-on definition. The Oxford English Dictionary calls the aphorism “a pithy observation that contains a general truth . . . a concise statement of a scientific principle, typically by an ancient classical author,” presumably a reference to the great doctor.

8.

James Geary, in his best-selling The World in a Phrase, gives a five-part definition of the form. It must be brief. It must be definitive. It must be personal. (I like his corollary: “This is what distinguishes the form from proverbs, for instance, which are really worn-out aphorisms that have had the identity of the original author rubbed away through repeated use.”) It must be philosophical. And it must have a twist.

9.

On Geary’s website, which serves in part as an appendix to the book, he distinguishes between aphorisms and twenty-eight other very small forms, including the adage, the apothegm, and the axiom. The best of these distinctions are very good: “A great maxim is also an aphorism. An inferior maxim is merely a rule of conduct. . . . A quotation is just something somebody said. . . . A sound bite is just something some politician said.” The weakest seem tacitly to acknowledge that, although some of the twenty-eight labels are essentially synonymic, one may as well finish the list: “A witticism, like an aphorism, can achieve immortality, but it is just funny rather than philosophical. . . . A quip has a shelf life of about 15 minutes. An aphorism is immortal.”

10.

Still, the proliferation of new names does not seem to be slowing. The term “greguería” was coined by Ramón Gómez de la Serna, the twentieth-century Spanish writer who defines it as “humor plus metaphor.” Some of his own: “The moon is the contact lens of the sky.” “The stray dog is looking for lost wallets.” “The egg has its wings hidden.”

This is how Geary, a former editor at Time, writes about aphorisms: “Trying to track the particles in [a] miniature big bang is like blowing up a haystack and trying to spot a needle as the debris flies past. Inside an aphorism, it is minds that collide and the new matter that spins out at the speed of thought is that elusive thing we call wisdom. Keep your eyes peeled or you’ll miss it.” I can’t blame him; after a fifty-century romp, starting with the I Ching, through some of the best examples of the form, it’s hard to resist having a go at it oneself.

12.

In his introduction to the Oxford book, Gross also sets out to distinguish aphorisms from other one-line forms: “All too often a maxim suggests a tag, a stock response, something waiting to be trotted out in the spirit of Polonius. . . . Without losing ourselves in a wilderness of definitions, we can all agree that the most obvious characteristic of an aphorism, apart from its brevity, is that it is a generalization. . . . The third distinguishing mark of an aphorism, in fact, is that it is a form of literature” — which is to say, it is signed by an author. I agree with the first and the third points.

13.

Gross gently dismantles his second point by adding, “Once or twice I have also broken the rule which says that aphorisms ought to deal with universals rather than particulars — but only, I hope, when the epigram in question readily lends itself to a more extended application.” He describes his collection as containing “a fair number of slightly longer passages, some poetry, a few mock-aphorisms, a sprinkling of miscellaneous outbursts and oddities.” I admire his editorial humility.

14.

Many of the best lines in Short Flights, James Lough and Alex Stein’s new collection of aphorisms by contemporary writers, appear in the introductory essays written by the aphorists themselves. In the poet James Richardson’s: “No one will ever write a novel by accident. A poem, too, takes time. But if I say ‘Pick a word’ and you say one, where did it come from? You certainly don’t say you ‘wrote it’ or ‘created it’ — more like you chose it, or it chose you. One-liners must be in the middle of that spectrum.”

15.

A fair number of aphorisms seek to justify or explain the form itself. Nietzsche: “It is my ambition to say in ten sentences what everyone else says in a whole book — what everyone else does not say in a whole book.” George Murray: “I describe them as poems without all the poetry getting in the way. But, for all I know, philosophers might describe them as thoughts without all the philosophy getting in the way.”

16.

A framing device is often used to give shape to a collection of aphorisms: the dictionary, as in Ambrose Bierce’s Devil’s Dictionary; the enumerated list, as in Pascal’s Pensées and Richardson’s Vectors; the alphabetical index-style series, as in Jenny Holzer’s Truisms; the novel, as in David Markson’s Reader’s Block tetralogy. And sometimes there is just accumulation.

17.

Maybe the aphorist’s goal — or some aphorists’ goal — is to achieve the permanence of the proverb while retaining authorship. It’s certainly the most efficient and least grandiose way to write for the ages. Or is it the smuggest, the most self-regarding? Whenever I decide that the form is one of noble modesty, it’s only a matter of time before I decide again that it is brash, lazy.

18.

JPJ’s little-known, self-published Last Aphorisms, the mysterious author’s first and, to date, only book, has won a small but devoted readership. It is rumored that JPJ is Canadian. A friend of a friend of mine has had some direct communication with him, but his anonymity remains intact; this is already more than I want to know.

19.

To my knowledge, JPJ did nothing to publicize the book; I heard about it from a friend who stumbled across it online. As JPJ says: “Ask a bird, ‘What is necessary for flight?’ and it will say, ‘Food and rest.’ ” The author’s silence confers a glamorous anonymity on these aphorisms, the illusion of their having come from a disembodied source. “Humans were taking pills long before there were any effective ones,” JPJ writes. “Likewise, we have not yet given up on prayer.”

20.

It occurs to me only now that JPJ could be a woman.

21.

Of the 500 or so writers in the Oxford anthology’s index, there are fifty women at most, and I’m not sure why these three lines by the poet Stevie Smith are among them: “Ceux qui luttent ce sont ceux qui vivent, / And down here they luttent a very great deal indeed. / But if life be the desideratum, why grieve, ils vivent.” I guess the first line (“Those who struggle are those who live”) sounds definitive yet personal. But why those three lines and not, say, anything by Elizabeth Bishop, such as “The gilt rubs off the edges of the pages and pollinates the fingertips”? There’s also one line from Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women: “House-keeping ain’t no joke.” Louise Bogan, another poet, gets a sentence from an essay: “True revolutions in art restore more than they destroy.” But why that sentence and not, say, “Once form has been smashed, it has been smashed for good, and once a forbidden subject has been released, it has been released for good”?

22.

Editing an anthology is a thankless task. No collection will ever be hailed as sufficiently thorough; every one of them will be faulted for, even defined by, its omissions.

23.

The women in the book who wrote actual stand-alone aphorisms are almost all French nobility. There are a couple of Germans, one Romanian by marriage, and one Japanese, the eleventh-century Sei Shonagon, who is also a rare non-Western writer in this bunch.

It is unsurprising that, before the Industrial Revolution, women with the leisure and education to write anything, let alone aphorisms, were primarily of royal or noble birth. What does surprise me is that there have been so few female aphorists since then.

25.

In Short Flights, the poet and essayist Sharon Dolin suggests that women don’t usually write aphorisms, which have “traditionally . . . dressed themselves in the suit of rhetorical authority.” Even now, people who cannot conceive of themselves as Great Men may be inclined to shy away from the form.

26.

“You should write an essay collection — you know, like Susan Sontag.” No fewer than three publishers have said these words to me, at different stages of my career. I don’t want to write a collection like that, I’ve always had to explain, as if it were irrational not to want to graduate to serious, adult, full-length forms — not to want to rise to the level of Sontag.

27.

Please don’t try to convince me that my romance with concision follows from the way we experience reality now, in interrupted and interruptive increments; or that if I like short literature I should be on Twitter; or that my taste is merely a symptom of a pathological inability to focus or commit; or that since I have a child I no longer have the time to write at length. I have always loved concision.

28.

I’m weary of the American idea that unless one is reaching toward the next, greater goal, one is effectively choosing failure. This cultural pressure to think big — to equate size with ambition — is especially burdensome for writers who cannot follow, or choose not to follow, in the footsteps of Great Men — who don’t fit the Hemingway–Mailer–Roth–Franzen mold.

29.

The word “small” is troublesome because it suggests small-mindedness. But “small” is still the best word to describe the aphorism. “Miniature” can’t help but recall dollhouse furniture or a one-inch-tall Bible. “Brief” describes duration, not form. The aphorism is small. I write to fill that small form, not as practice for someday filling larger forms.

30.

Have one- to five-sentence pieces of writing become especially hard to value because most of them exist on Twitter — i.e., because they no longer cost money to publish or read? Is it idle, cheap, or old-fashioned of me not to want to give up my work to Twitter’s faceless roar?

31.

With the Highlight function, Amazon’s Kindle now offers readers a pre-highlighted version of whatever book they buy, with a count of how many times a passage has been marked. I can’t pretend I’m really rescuing a sentence that has already been rescued by so many others.

32.

Why read a book when you could buy Cheryl Strayed’s Brave Enough, a digest of 132 bite-size passages from her three previous books? Despite its redundancy, it will outsell most other books published this year. (I don’t blame Strayed for publishing it.) Maybe such digests will become the publishing industry’s go-to gambit for dealing with high demand and low volume. After all, Reader’s Digest, published since 1922, maintains a paid circulation in the United States of 3 million.

33.

In an age of compulsive shortness and shortening, of simplification and shrinking attention spans, of Twitter and opinions about Twitter, the aphorism may seem inessential, or worse; enough brevity already.

34.

This would be a mistake. Brevity isn’t the soul of witlessness; shallowness is. Ezra Pound: “Great literature is simply language charged with meaning to the utmost possible degree.”

35.

The brevity of fragments, scraps, the collective brain lint of the internet, is one thing; the brevity of the best aphorisms, which are complete in themselves, quite another.

36.

The best aphorisms fulfill the impossible demand that Charles Simic made of the short poem: “Be brief and tell us everything.”