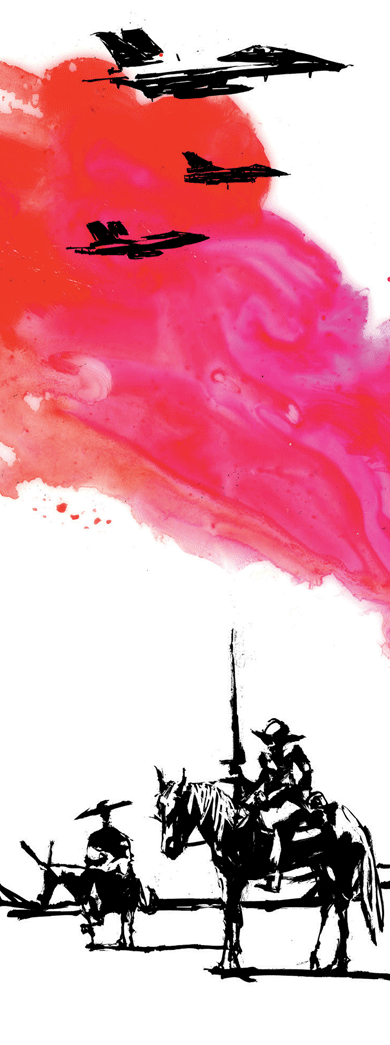

Not long after setting out on his first adventures, Don Quixote is invited to share a frugal meal with a group of goatherds. A little meat stew, plenty of wine. When they finish, the goatherds spread out hard cheese and a quantity of acorns, which they start cracking open for dessert. Don Quixote just rolls a few in his hand, lost in a reverie. He clears his throat. Fortunate the age and fortunate the times called golden by the ancients, he tells the chewing peasants. It was an age when nature’s bounty lay ready to be gathered. There was no mine and thine, no farms, no making of farm tools, no makers of farm tools. Modest shepherdesses, simply attired, roamed the hills unmolested, stopping only to hear the spontaneous, unaffected poetry of their chaste lovers. No laws were enforced because none were needed.

That age ended. Why? The goatherds do not ask, and Quixote doesn’t burden them with his esoteric knowledge. He just reminds them of what they already know: now maidens and even orphans are not safe from predators. When the Golden Age ended, laws became necessary, but since there were no pure hearts left to enforce them, the strong and vicious were free to terrorize the weak and good. That was why the order of knights was created in the Middle Ages, and why Quixote has resolved to revive it. The goatherds listen in “stupefied and perplexed” silence to this old man in his papier-mâché helmet. Sancho Panza, already used to his master’s harangues, continues drinking.

Quixote has convinced himself that once upon a time the world really was as it was meant to be, that the ideal had been made flesh before it vanished. His suffering is Christian; he awaits the Second Coming. His quest is doomed from the start because he is rebelling against the nature of time, which is irreversible and unconquerable. What is past is past; this is the thought he cannot bear. Chivalric literature has robbed him of irony, the armor of the lucid. Irony may be defined as the ability to negotiate the gap between the real and the ideal without doing violence to either. Quixote is under the illusion that the gap he perceives was caused by a historical catastrophe, not that it is simply rooted in life.

This fantasy is sustained by an assumption about history: that the past comes already divided into discrete, coherent ages. An “age,” of course, is nothing more than a space between two markers that we place on the ticker tape of time to make history legible to ourselves. We do the same by carving “events” out of the chaos of experience, as Stendhal’s Fabrice del Dongo discovers in his futile search for the Battle of Waterloo. To put some order in our thinking, we must impose a rough-and-ready order on the past. We speak metaphorically of the “dawn of an age” or “the end of an era” without meaning that at some precise moment we crossed a border. When the past is remote, we are especially aware of our imprecision, and nothing seems particularly at stake if, say, we move the boundaries of the Pleistocene or the Stone Age forward or back a millennium. The distinctions are there to serve us, and when they don’t we revise them or ignore them. In principle, what taxonomy is to biology, chronology should be to history.

But the closer we get to the present, and the more our distinctions concern society, the more charged chronology becomes. This is also true of taxonomy. The concept of race has one resonance when applied to plants, another when applied to human beings. The danger in the latter is reification. That happens when we develop a concept to help make sense of reality (the Aryan linguistic group, for example), then subsequently declare it to be a fact inscribed in reality itself (a homogeneous Aryan people with a distinct culture and history). We are learning not to do that with race, but when it comes to understanding history we are still incorrigibly reifying creatures.

The urge to divide time into ages seems embedded in our imaginations. We notice that the stars and the seasons follow regular cycles and that human life follows an arc from nothingness to maturity, then back to nothingness. For civilizations ancient and modern this movement in nature has provided irresistible metaphors for describing cosmological, sacred, and political change. But as metaphors age, and migrate from the poetic imagination to social myth, they harden into certainties. One need not have read Kierkegaard to know the anxiety that accompanies historical consciousness, that inner cramp that comes when time lurches forward and we feel ourselves catapulted into the future. To relax that cramp we tell ourselves that we actually know how one age has followed another since the beginning. This white lie gives us hope of altering the future course of events, or at least of learning how to adapt to them. There even seems to be solace in thinking that we are caught in a fated history of decline, so long as we can expect a new turn of the wheel, or an eschatological event that will carry us beyond time itself.

Epochal thinking is magical thinking. Even the greatest minds succumb to it. For Hesiod and Ovid the “ages of man” was an allegory, but for the author of the Book of Daniel the four kingdoms destined to rule the world were a prophetic certainty. Christian apologists from Eusebius to Bossuet saw God’s providential hand shaping distinct ages to mark the preparation, revelation, and spread of the Gospel. Ibn Khaldun, Machiavelli, and Vico thought that they had discovered the mechanism by which nations rise from rude beginnings before reaching their peak, decaying into luxury and literature, then returning cyclically to their origins. Hegel divided the history of nearly every human endeavor — politics, religion, art, philosophy — into a snaking temporal web of triads within triads. Heidegger spoke elliptically about “epochs” in “the history of Being” that are opened and closed by a destiny beyond human understanding (though it sometimes leaves signs, like the swastika). Even our minor academic prophets of the postmodern, by using the prefix post-, can’t seem to overcome the compulsion to divide one age from another. Or to consider their own to be the culminating one, in which all cats are finally revealed to be gray.

Narratives of progress, regress, and cycles all assume a mechanism by which historical change happens. It might be the natural laws of the cosmos, the will of God, the dialectical development of the human mind or of economic forces. Once we understand the mechanism, we are assured of understanding what really happened and what is to come. But what if there is no such mechanism? What if history is subject to sudden eruptions that cannot be explained by any science of temporal tectonics? These are the questions that arise in the face of cataclysms for which no rationalization seems adequate and no consolation seems possible. In response, an apocalyptic view of history develops. It sees a rip in time that widens with each passing year, distancing us from an age that was golden or heroic or simply normal. In this vision there really is only one event in history, the kairos separating the world we were meant for from the world we must live in. That is all we can know, and must know, about the past.

Narratives of progress, regress, and cycles all assume a mechanism by which historical change happens. It might be the natural laws of the cosmos, the will of God, the dialectical development of the human mind or of economic forces. Once we understand the mechanism, we are assured of understanding what really happened and what is to come. But what if there is no such mechanism? What if history is subject to sudden eruptions that cannot be explained by any science of temporal tectonics? These are the questions that arise in the face of cataclysms for which no rationalization seems adequate and no consolation seems possible. In response, an apocalyptic view of history develops. It sees a rip in time that widens with each passing year, distancing us from an age that was golden or heroic or simply normal. In this vision there really is only one event in history, the kairos separating the world we were meant for from the world we must live in. That is all we can know, and must know, about the past.

Apocalyptic history itself has a history, which stands as a record of human despair. The expulsion from Eden, the destruction of the First and Second Temples, the crucifixion of Jesus, the sack of Rome, the murders of Ali and Hussein, the Crusades, the fall of Jerusalem, the Reformation, the fall of Constantinople, the English Civil Wars, the French Revolution, the American Civil War, World War I, the Russian Revolution, the abolition of the caliphate, the Shoah, the Palestinian Nakba, the Sixties, 9/11 — all these events have been inscribed in various collective memories as definitive breaches in history. For the apocalyptic imagination, the present, not the past, is a foreign country. That is why it is so inclined to dream of a second event that will blow open the doors of paradise. Its attention is fixed on the horizon as it awaits the Messiah, the Revolution, the Leader, or the end of time itself. Only an apocalypse can save us now: in the face of catastrophe this morbid conviction can appear to be simple common sense. But throughout history it has also provoked extravagant hopes that were inevitably disappointed, leaving those who held them even more desolate. The doors to the Kingdom remained shut, and all that was left was a memory of defeat, destruction, and exile.

For those who have never experienced defeat, destruction, or exile, there is an undeniable charm to loss. An agency in Romania offers what it calls a Beautiful Decay Tour of Bucharest, which gives the visitor an overview of the postcommunist urban landscape — buildings full of rubble and broken glass, abandoned factories invaded by local vegetation, that sort of thing. Young American artists, feeling unappreciated in gentrified New York, are now moving to Detroit, America’s Bucharest, to feel the grit once more in their teeth. English gentlemen succumbed to something similar in the nineteenth century, buying up deserted abbeys and country houses where they shivered on the weekends. For romantics, the decay of the ideal is the ideal.

La nostalgie de la boue is alien to history’s victims. Finding themselves on the other side of the chasm separating past and present, some recognize their loss and turn to the future, with hope or without it: the camp survivor who never mentions the number tattooed on his arm as he plays with his grandchildren on a Sunday afternoon. Others remain at the edge of the chasm and watch the lights recede on the other side, night after night, their minds ricocheting between anger and resignation: the aged White Russians sitting around a samovar in a chambre de bonne, the heavy curtains drawn, tearing up as they sing songs from the old country. Some, though, become idolaters of the chasm. They are obsessed with taking revenge on whatever Demiurge caused it to open up. Their nostalgia is revolutionary. Since the continuity of time has already been broken, they begin to dream of making a second break and escaping from the present. But in which direction? Should we find our way back to the past and exercise our right of return? Or should we move forward to a new age inspired by the golden one? Rebuild the Temple or found a kibbutz?

The politics of nostalgia are about nothing but such questions. After the French Revolution, dispossessed aristocrats and clergy camped along the border, confident that they would return home shortly and set the furniture aright. They had to wait a quarter-century, and by then France no longer was what it had been. The Bourbon Restoration wasn’t one. Yet nostalgic Catholic monarchism remained a strong current in French politics until World War II, when movements like the Action Francaise were finally disgraced for collaborating with the Vichy regime. Small groups of sympathizers still exist, though, and the newspaper L’Action Française 2000 continues to appear on newsstands, like a specter, every two weeks. Germany’s defeat in World War I pushed Adolf Hitler in the opposite direction. He might have projected the image of a restored old Germany of conservative villages nestled in Bavarian valleys, populated by Hans Sachses who could sing and fight. Instead he spoke of a new Germany inspired by the ancient tribes and the Roman legions, now riding Panzer tanks unleashing storms of steel and ruling over a hypermodern industrial Europe cleansed of Jews and Bolsheviks. Forward into the past.

Apocalyptic historiography never goes out of style. Today’s American conservatives have perfected a popular myth of how the nation emerged from World War II strong and virtuous, only to become a licentious society governed by a menacing secular state after the Nakba of the Sixties. They are divided over how to respond. Some want to return to an idealized traditional past; others dream of a libertarian future where frontier virtues will be reborn and internet speeds will be awesome. Things are more serious in Europe, especially in the east, where old maps of Greater Serbia, which had been in cold storage since 1914, were pulled out as soon as the Berlin Wall fell, and Hungarians began retelling old tales about how much better life was when there weren’t so many Jews and Gypsies around. Things are critical in Russia, where all problems are now attributed to the breakup of the U.S.S.R., allowing Vladimir Putin to sell dreams of a restored empire blessed by the Orthodox Church and sustained by pillage and vodka.

But it is in the Muslim world that belief in a lost Golden Age is most potent and consequential today. The more deeply one reads into the literature of radical Islamism, the more one appreciates the appeal of the myth. It goes something like this: Before the arrival of the Prophet the world was in an age of ignorance, the Jahiliyya. The great empires were sunk in pagan immorality, Christianity had developed a life-denying monasticism, and the Arabs were superstitious drinkers and gamblers. Mohammed was then chosen as the vessel of God’s final revelation, which uplifted all individuals and peoples who accepted it. The companions of the Prophet and the first few caliphs were impeccable conveyors of the message, and began to construct a new society based on divine law. But soon, astonishingly soon, the élan of this founding generation was lost. And it has never been recovered. In Arab lands conquerors came and went — Umayyads, Abbasids, Christian Crusaders, Mongols, Turks. When believers remained faithful to the Koran there was some semblance of justice and virtue, and there were a few centuries when the arts and sciences progressed. But success brought luxury, and luxury bred vice and stagnation. The will to impose God’s sovereignty died.

At first, the arrival of the colonial powers in the nineteenth century appeared to be just another Western Crusade. But in fact it presented a wholly new and far graver challenge to Islam. The medieval Crusaders wanted to conquer Muslims militarily and convert them from one religion to another. The modern colonizers’ strategy was to weaken Muslims by converting them away from religion altogether and imposing on them an immoral secular order. Rather than meet holy warriors on the battlefield, the new Crusaders simply held out the trinkets of modern science and technology, mesmerizing their foes. If you abandon God and usurp His legitimate rule over you, they purred, all this will be yours. Very soon the talisman of secular modernity did its work. Muslim elites became fanatics of “development,” sending their children — including girls — to secular schools and universities, with predictable results. They were encouraged in this by the tyrants who ruled over them with the West’s support and at its bidding suppressed the faithful.

All these forces — secularism, individualism, materialism, moral indifference, tyranny — have now combined to bring about a new Jahiliyya, which every faithful Muslim must struggle against, just as the Prophet did at the dawn of the seventh century. He did not compromise, he did not liberalize, he did not democratize, he did not pursue development. He spoke God’s word and instituted His law, and we must follow his sacred example. Once that is accomplished, the glorious age of the Prophet and his companions will return for good. Inshallah.

There is little that is uniquely Muslim in this myth. Even its success in mobilizing the faithful and inspiring acts of extraordinary violence has precedents in the Crusades and in Nazi efforts to return to Rome by way of Valhalla. When the Golden Age meets the Apocalypse the earth begins to quake.

What is striking is how few antibodies contemporary Islamic thought has against this myth, for reasons historical and theological. Among the jewels of wisdom and poetry in the Koran one also encounters a degree of insecurity, unusual in sacred texts, about Islam’s place in history. From the very first suras we are invited to share Mohammed’s frustration at being rebuffed by Jews and Christians, whose prophetic legacy he came to fulfill, not abolish. No sooner does the Prophet begin his mission than history goes a little off course and an adjustment has to be made for “peoples of the Book” blind to the treasure laid before them. St. Paul confronted a similar challenge in his Epistles, in which he counseled peaceful coexistence among gentile Christians, Jewish Christians, and Jewish non-Christians. Some Koranic verses are generous and tolerant about resistance to the Prophet. Far more are not. The Koran has an unmistakable chip on its shoulder about its belatedness that can be easily exploited by those who have chips on their shoulders about the present. Untrained readers ignorant of the deep intellectual traditions of Koranic interpretation, who for whatever reason feel or can be made to feel angry about their conditions of life, are easy prey for those who would use the Koran to teach that historical grudges are sacred. From there it is not a large step to begin thinking that historical revenge is sacred, too.

Once the butchery ends, as it eventually must, through exhaustion or defeat, the pathos of political Islamism will deserve as much reflection as its monstrosity. One almost blushes to think of the historical ignorance, the misplaced piety, the outsized sense of honor, the impotent adolescent posturing, the blindness to reality and fear of it that lay behind the murderous fever. The pathos of Quixote is quite different. The Knight of the Sorrowful Face is absurd but noble, a suffering saint stranded in the present who leaves those he meets improved, if slightly bruised. He is a flexible fanatic, occasionally winking at Sancho Panza as if to say, Don’t worry, I’m onto myself. And he knows when to stop. After being defeated in a mock battle arranged by friends hoping to wake him from his dreams, he renounces chivalry, falls ill, and never recovers. Sancho tries to revive him by suggesting that they retire to the countryside and live together as simple shepherds, as in the Golden Age. But it’s no use; the knight meets death humbly. A triumphant, avenging Quixote is unthinkable.

The literature of radical Islamism is a nightmare version of Cervantes’s novel. Those who write it feel stranded in the present, too, but have divine assurance that what is lost in time can be found in time. To God, the past is never past. The ideal society is always possible, since it once existed and there are no social conditions necessary for its realization; what has been and must be, can be. All that’s lacking is faith and will. The adversary is not time itself, it is those who in every historical epoch have stood in God’s way. This powerful idea is not new. Considering the conservative reactions to the revolutions of 1848, Marx wrote that in epochs of revolutionary crisis we “anxiously conjure up the spirit of the past” to comfort ourselves in the face of the unknown. He was confident, though, that such reactions were temporary and that human consciousness was destined to catch up to what was already happening in the material world. Today, when political bedtime stories seem more potent than economic forces, it is hard to share his confidence. We are only too aware that the most revolutionary slogans of our age begin: Once upon a time . . .