Discussed in this essay:

Late to the Ball: Age. Learn. Fight. Love. Play Tennis. Win., by Gerald Marzorati. Scribner. 288 pages. $26.

Federer and Me: A Story of Obsession, by William Skidelsky. Atria. 272 pages. $24.

String Theory: David Foster Wallace on Tennis, introduction by John Jeremiah Sullivan. Library of America. 158 pages. $19.95.

There are a lot of connections to be made here, but we must start with the irrelevant and unimportant fact that in 2008 I sold — or was about to sell — my just-finished novel to a new publisher. I was fifty, and they understandably wanted to know what I had left in the tank. Plenty, I assured them, even though I suspected I might be, as John McEnroe likes to say, running on fumes. So what was I thinking of writing next? A book about tennis, I said. While I’d been struggling to write the just-finished novel my wife kept reminding me that if I spent half the time writing that I did obsessing about tennis, I’d have finished it ages ago. I’d always written about what interested me most, and nothing at that point interested me more than tennis. And it wasn’t only me. With Andy Murray gnawing his way closer to the Wimbledon title, tennis had become more popular in Britain than it had been since the headband era of Borg–McEnroe. The top seed at my new publisher was one of my regular tennis partners; he liked the idea of a book about tennis at fifty and I liked the idea of seeing how good I could get at this past-midpoint in my life.

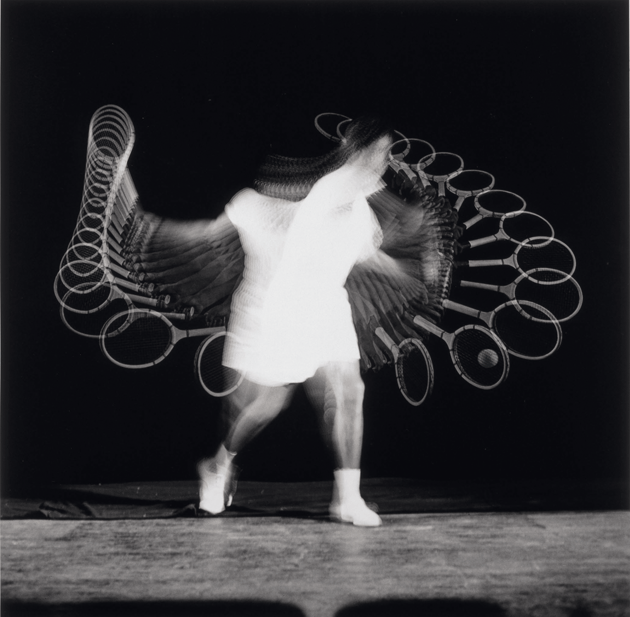

“Pancho Gonzales,” 1949, by Harold E. Edgerton © Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington/Art Resource, New York City/MIT. Courtesy MIT Museum and Gus Kayafas/Palm Press

As a perennial bottom-feeder for whom writing has always doubled as a way of getting free shit, I was also hoping that a top-notch coach might be willing to give me lessons in return for the massive exposure guaranteed by inclusion in the book. Maybe a major sponsor would come on board if I slimed in a couple of paragraphs about how my game had improved beyond recognition once I started playing exclusively with Head rackets, Babolat strings, or Wilson sweatbands. At the very least I’d be able to claim the cost of balls and court fees against tax.

There were benefits on the writing side, too. It was time to start working like a professional man of letters for whom book-writing is like being on the A.T.P. tour: finish one book/tournament, spend the weekend shopping, and then move right on to the next. My pattern was to finish a book, sink into terrible depression, and do nothing until I got so depressed that doing nothing became even more terrible than doing something — at which point I’d begin the long, exhausting effort to get back in shape. It was like Agassi spiraling down to satellite tournaments before bouncing back, except that when it comes to writing nobody gives a toss — or even notices — whether you’re doing it anymore (and it’s not like I’d ever been ranked that highly anyway). Moving straight on to the tennis book would break this miserable cycle. There was much excitement and hugging as the deal was done and a two-book contract signed. In fact, as I should have known, the contract just dragged me deeper into depression, because the obligation to produce a book only intensified my aversion to writing it. There was another physical factor, which I’ll come back to later, but the bottom line is that I didn’t write the book about tennis. It all turned out okay because, as a diversion, I started summarizing the film Stalker, and this gradually turned into a book about the film director Andrei Tarkovsky, which the publisher gracefully accepted in lieu of the book on tennis. Phew.

But it’s kept nagging at me, the thought of that unwritten masterpiece. I mean, it’s not as if I’m no longer interested in tennis. I’m actually more interested in it than ever. In my early forties I used to do the English thing and just watch Wimbledon; then my interest expanded to include the three other Grand Slams; now that I’m bumming a friend’s log-in details for the Tennis Channel I watch everything from the Chennai Open to the Fallujah Closed. I’m also better informed about more of the players and the lives they lead. The internet has a lot to do with this, obviously. You know, you’re reading about Tomáš Berdych (a player you’d had zero interest in until Murray’s loyal wife, Kim Sears, was caught shouting “Fucking have that, you Czech flash fuck” during a tense match at last year’s Australian Open) and then you’re reading about Berdych’s wife and then you’re looking at pictures of her and before you know it you’re like the character at the start of Ardashir Vakil’s novel One Day, reading The Inner Game of Tennis in bed while his wife masturbates beside him.

Since I was still crazy about the inner and outer game I started wondering if I could shift the abandoned project back a decade — to tennis at sixty. But now I discover that I’ve missed the bus, that Gerald Marzorati got there early with Late to the Ball, a book about getting very serious about tennis at sixty — which sounds incredibly ancient even though I’m writing this a few days after turning fifty-eight. It’s a perfectly decent book and I wish him well, hope he’ll be around to add a postscript to a future edition updating us on how his game and his knees are holding up at seventy. It’s fun to read; there’s probably not a single thing anyone can disagree with in the whole book. But it’s also a bit dull to read because there’s scarcely an interesting sentence in the whole book. Which is or is not to be expected given that Marzorati is a former editor of The New York Times Magazine, with the experience of “decades of editing stretching back to the 1970s.” Does this mean improving people’s writing, or just ironing out the wrinkles, getting it to conform to an undeclared but time-honored ideal of style as essentially invisible? Certainly it’s one of the curious but inescapable facts of literary life that skill as an editor has no bearing at all — either positive or negative — on one’s ability to write.

In tennis terms, having been a coach for all these years, Marzorati has now become a player. Tennis and writing — which is what this essay is about, after all — mirror each other in that within certain shared rules one’s style is as thoroughly imprinted with one’s DNA as a strand of hair. There is broad agreement on how to execute each stroke, coaches are always trying to smooth out little kinks in someone’s game — and yet a player’s style remains so distinctly his or her own that, even if their faces and clothes were blurred out, we would recognize any of the stars by their movements alone. When it comes to your own game a reverse process is in operation. This is what might be termed the Rimbaud or Je est un autre syndrome.

At a high-tech tennis camp in Utah, Gerald is filmed while playing, so that he can see what needs adjusting. He’s hitting contentedly, feeling rather pleased with his stylish backhand slice. When he is shown the video later this backhand slice turns out to be nothing like as smooth as he’d imagined. At which point it becomes tempting to mistranslate the Rimbaud quote along the lines of the International Tennis Federation’s damning verdict on Maria Sharapova’s meldonium bust: I is the sole author of my misfortune. But the really distressing thing “was not my slice but simply seeing my aging self.” Being “neither overweight nor balding, I had flattered myself that I looked younger than I was,” he writes. On the screen, “I looked every bit my age.”

But Gerald keeps at it — “I like persevering” — and keeps getting better, even when this means getting worse. He’s willing to have his serve dismantled in order to properly reconstruct it. Impressive in itself, this would have been still more admirable if he’d done the same with his prose. Then we might have been spared the likes of “I was in a mood as bright as the day.” One of the reasons my own style — sorry, I mean my own game — is such a hog’s dinner is that, until recently, I could never bring myself to shell out for lessons, so I was happy to cadge a few secondhand tips from Late to the Ball, only the simplest of which — hold the racket loose on a sliced backhand — I’ve persevered with. So I shouldn’t be too critical. After all, as men of a certain age, Marzorati and I are partners rather than opponents, content still to be playing, even if that contentment regularly finds expression as soul-destroying torment. The biggest torment is that I can’t play as frequently as I would like. In this regard, the relationship between tennis and sex is quite instructive. When I was young I could, if you’ll permit a little exaggeration, play tennis and fuck all day. Now that I’m older I can’t do either nearly as often. With sex, my desire has diminished, so there is no frustration. I have less sex partly because I want less. With tennis, the desire is as huge as ever — I just can’t get it up (and over the net) as often. Or, and it may be the same thing, I need longer to recover. It’s a fine line between playing as much as possible and playing so much that you get injured. If I play as much as I want to I get hurt and play less than I did before I played as much as I could. But when I am playing it’s bliss. I look at the young guys on the courts next to mine, whacking the ball back and forth like there’s no tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow, and I know that no one is happier than I. Because I’m still playing.

Sort of. Unlike Marzorati I no longer serve (shoulder problems), so by “playing” I mean just rallying, or that compromised version of competition whereby a point is initiated by feeding the ball to your opponent and the winner is the first to eleven points. It’s not like playing sets, but at some level — the canine, I suppose — if you keep hitting the ball to me I’ll keep chasing after it and my tail will be wagging. But did it used to wag more vigorously? I ask myself, wondering when I was at my peak. It’s hard to say because at some level — deluded, surely — I believe I’m playing better than ever. At the same time, I also have a deluded sense of how good I used to be. (McEnroe is fond of quoting Connie Hawkins’s observation: the older I get, the better I used to be.) From this jumble of delusions the only logical conclusion is that I’ve never been at my peak. One thing I do know is that I suffered a wrist injury that kept me out of the game for a year, at exactly the time that I was supposed to be writing my wretched book on tennis. That was a huge setback in the ongoing setback called life.

I was playing in Islington, in London. The courts, as usual, were slightly damp behind the baseline. My opponent and I had spent the entire morning texting each other, monitoring the weather. In the end, we played between rain showers, I slipped and fell, kept playing, and ended up having surgery on torn cartilage in my wrist. Who was I playing on that fateful day? None other than William Skidelsky, author of Federer and Me: A Story of Obsession.

“Tennis Ball Bounce,” 1977, by Harold E. Edgerton © VAN HAM Kunstauktionen/Saša Fuis/MIT. Courtesy MIT Museum

Because Will is a friend I can’t review his book objectively, but I can offer the gossip-hungry readers of Harper’s Magazine exclusive dope on some of his tennis partners. I can reveal, for example, that the Indian novelist with the “uneven temperament” and an “almost disdainful style” is Ardashir Vakil — last heard of in the fourth paragraph, imaginatively poring over The Inner Game of Tennis — and that the publisher who “never seemed to sleep,” and who Skidelsky plays at eight in the morning, is Jamie Byng, the very publisher who had signed me up to write the unwritable tennis book. Skidelsky is excellent about the technical aspects of Federer’s game, but he is understandably bamboozled by Byng, who is not, as stated, simply a lefty: he serves with his left hand but then plays with his right. By far the most important character in Skidelsky’s non–roman à clef, however, is “a tall Englishman whose game was awkward and inelegant but doggedly effective.” This description is a slight improvement on the U.K. proof copy, where “beanpole” was preferred to “tall,” but listen as I say this slowly and clearly. That. Cannot. Be. Me. When I confronted Will, he said that this ungainly specimen was a composite of me and the lanky American novelist Ben Markovits. (I played him once, and his game was so inelegant and ineffective I worried it might be infectious.) Then, a little while later, Will came clean and admitted that he was referring to me.

This raised again the question Marzorati faced when he watched the video evidence of his own aging ineptitude. When we look in the mirror can we ever see ourselves as others see us? I really can’t believe my game is inelegant. I just can’t — even if, at the pedantic level of fact-checking, such a claim is deemed plausible or accurate. So even though you’ve seen fit to wash your dirty linen in public like this, shorty, I will refrain from mentioning that it wasn’t me who turned up at the Islington Tennis Centre wearing a Rastafarian headband. 15–0! I also won’t sink low enough to point out that while I may have been the crappiest player of this quartet, my game would presumably have gotten off to a better start if, like you and Byng, I’d lived in a stately home with a tennis court in the back garden. 30–0! Byng: I’ll forget that you still owe me for your share of the indoor-court fee for that game on January 20, 2013. 40–0! As for Ardu, the world is better off not knowing about those famously dodgy line calls. Game, set, and match!

To give credit where it is due, Skidelsky was always the Roger Federer of our little cohort. Impeccably mannered and pleasant, on court he became the embodiment of elegant aggression. Honestly, it was generous of him even to share a court with me, but as my main partner from that time, the ominously named Dan Perfect, always said: you’re willing and you’re available.

And unlike Dan (golf, I’ve heard), I’m still available, and playing in more perfect circumstances than ever, at the courts by the ocean in Santa Monica. I’ve even forked out for lessons with a coach, Dial Jones, who has done exactly what was asked: introduced small, achievable changes rather than going for a deep archaeological excavation of my game and psyche. One day I asked Dial what he was reading and he replied that he had just started a book about a tennis academy. He couldn’t remember the author’s name but it was a big book. Maybe the guy’s name was David Something?

“David Foster Wallace?” I said. “Infinite Jest?”

“That’s it.”

“Ten bucks says I’ll have a backhand like Stan Wawrinka before you finish that sucker,” I said. He didn’t take the bet, but a few weeks later he addressed me as “Stan” rather than the usual “Albatross” (on account of my long reach) and conceded that he hadn’t made much progress with Jest. He doesn’t need to, now that Wallace’s non-fiction tennis writing has been collected in one lovely edition. String Theory includes the early piece on growing up playing tennis in wind- and tornado-swept Illinois, the tremendous profile of Michael Joyce (then ranked seventy-ninth in the world, now best known as the subject of that piece), and, of course, the meditation on Roger Federer. Marzorati was at this magazine in the early 1990s when it published “Derivative Sport in Tornado Alley” (under the title “Tennis, Trigonometry, and Tornadoes”), and later got into a protracted rally with Wallace at the New York Times because his use of the serial comma in the Federer essay contravened house style. (Wallace eventually won the point by threatening to withdraw the piece.) Skidelsky’s book is, in some ways, a lengthy postscript and response to the essay in which Wallace unstitched the conventional wisdom that Federer was a throwback to an earlier, less bruising era of play by pointing out that all the gorgeous finesse and touch operated within the game of “a first-rate, kick-ass power-baseliner.”

In Late to the Ball, Marzorati watches his coach, Kirill, get creamed in a match. There was nothing Kirill could do. The other guy, he laments, “was painting the lines from the beginning.” That’s what Wallace is doing in these pieces. Every line has, as they say, some English on it (English in the sense of American). The power of expression is inseparable, of course, from the encyclopedic scale of observation, the depth — but apparent instantaneity — of thought. Along with everything else, it’s also a reminder of what a great comic writer Wallace was, partly because he is so much more than comic, and partly because of the persona that emerges, stylistically fully formed (“I was an unpopular player, with good reason”), from the first page. It’s actually not as easy to write about yourself as is sometimes assumed. Self-indulgence — and few reporters have indulged themselves more lavishly and expansively than Wallace — has its own concealed restraints, its own self-discipline. Marzorati and Skidelsky dutifully transcribe what happened to them in real life. Occasionally one even feels a little embarrassed about their modest disclosures in a way that never happens, for example, when Maggie Nelson tells us she is getting fucked in the ass or whatever. Frankness and honesty have nothing to do with it. It’s all about style. Wallace creates himself on the page. To conflate that remark of Kirill’s with his description of Federer — “Mozart and Metallica at the same time” — he is the paint and the lines.

So Marzorati is right. “In his too-brief life Wallace had come to observe tennis more ingeniously than any American writer ever had.” This, to extend something Wallace says in the Joycean piece, is “a fundamentally different grade” of tennis writing. If the competition is less brutal than in the nearby stadium showcasing boxing and literature, that is partly because tennis is extraordinarily difficult to write about. There’s a bit in the Federer essay where Wallace dissects a sequence of play from a match with Rafael Nadal. It reads like an updated version of a passage from John McPhee’s wooden-racket-era book Levels of the Game (1969) about a match between Arthur Ashe and Clark Graebner — with Big Bang strings, an extreme western grip, and fearsome amounts of stylistic topspin thrown in. But it reminds you that at some point the nature of the task obliges even the most ingeniously resourceful writer to resort to phrases like “backhand down the line” or “crosscourt forehand.” Tracy Austin’s autobiography was so inane it broke Wallace’s heart, but her account of the U.S. Open final against Chris Evert — “at 2–3, I broke Chris, then she broke me, and I broke her again, so we were at 4–4” — is, in a sense, what it all comes down to.

Everything about tennis is easier to describe than the actual progress of a point. You can write about the circumstances surrounding the courts, whether that means ditches “heaving with what looked like conventions of copperheads” in Illinois or “a whole inland sea of sunglasses and hats” at the U.S. Open. You can write about the way that gut strings become “pasta” when wet. You can note “the ropy arteries” of players’ forearms. You can scrutinize their habits, their temperaments (“spring-loaded on a tantrum”), and their outfits (Sampras, with “powder-blue shorts swimming down around his knees, looks a little like a kid wearing his father’s clothes”). You can run these things together and animate them so that Richard Krajicek “wears a tiny white billed hat in the sun and rushes the net like it owes him money and in general plays like a rabid crane.” You can do all this but at some point there will be a crosscourt forehand to level things up at four apiece. Norman Mailer’s blow-by-blow account of the Ali–Foreman encounter in Zaire is not just like watching the fight, it’s like living through it. A prose description of a tennis point is like reading about it.

Wallace is acutely conscious of this, of the way that great athletes operate in a zone beyond words. This was best expressed by the poet William Scammell’s uncertainty, as he watched Björn Borg, about what was going on in that blond head,

whether chess against a breaking wave

or just a corny Abba tune.

Or, as Wallace puts it in the essay on Tracy Austin, could it be “nothing at all”? A massive effort of linguistic framing is necessary to articulate that nothing. The built-in irony becomes especially pronounced in the essay on Federer, whose grace is essential in the sense that it has been achieved through the elimination of everything extraneous. No one would make such a claim about Wallace’s writing, which proceeds by relentless elaboration and accumulation. The dudely baroque of a Wallace paragraph depends as much on the tics — the footnotes, the asides, the sort ofs, kind ofs, and good olds — as it does on the overhead vocabulary (“katexic,” “candent”) and the out-of-nowhere winners loaded with philosophical swirl and backspin. As a writer Wallace is as compulsive as Nadal, forever rearranging his water bottles and pulling his shorts out of the crack of his ass; he’s as twitchy as Lleyton Hewitt; as much a monologuist as Murray. This, it needs emphasizing, is all part of the fun. But it’s so unlike Federer, whom Wallace has to observe “very closely” to find the tiniest quirk, which “happens very fast” and lasts “just for an instant.” (And which is so tiny it’s not even worth mentioning here.)

The Federer article was first published in 2006, when Roger was at his peak, when he had rendered “the game’s future . . . unpredictable.” Ten years later, when that future, predictably, has rolled into view, with Federer in the gloaming of his career, we are poignantly conscious of the enormous privilege of watching him play. This is partly a function of his longevity, the sheer extent of rivalries stretching back to poor (i.e., very rich) Andy Roddick, who pointed out, with great charm, that for it to be a proper rivalry he would need to win occasionally. Nadal began chipping away at Federer’s invincibility by relentlessly targeting the single most beautiful part of Federer’s game, his one-handed backhand. The difficulty of dealing with shoulder-high topspin balls to his backhand took its toll. In retrospect it looks like Nadal used himself up before he wore Federer out, but then came Djokovic and the increasingly familiar prospect of Roger gliding effortlessly through a tournament until unraveling against the Serbian.

It’s painful to see — or would be, were it not for the fact that Roger seems, as they say in the jazz world, such a beautiful cat these days. Where there was once the suggestion of a polite but Ozymandian sneer of cold command, now there is serenity — of a fiercely competitive kind. We all want him to win one more Slam. We don’t want his haul of seventeen to be surpassed by anyone, and certainly not Djokovic, who, like Nadal a few years ago, is coming dangerously close. There’s no need to despair. Federer can still beat Djokovic — if everything in the tournament and in the match itself goes his way. If he gets through the early rounds easily. If he serves at his best. If there’s no wind. If he wins the first two sets. If this, if that. But Djokovic could still win even if everything went against him including a rain-delayed five-setter the previous day followed by an all-night party in the neighboring suite at the Hotel Serbia. The alternative is that someone else take out Djokovic, leaving Roger with a nemesis-free tilt at the title, as happened when Robin Söderling settled Nadal’s hash at the French Open of 2009 — before being slaughtered by a grateful Federer in the final. Sam Querrey duly obliged at Wimbledon this year, only for Roger to succumb to Milos Raonic in the semis. All of which means that we now appreciate, more profoundly than ever, that brief phase when Roger canceled out the long-running opposition between pragmatism and beauty. The most efficient way to play was also the most beautiful. It’s lovely to be reminded of that, especially now that it’s no longer true.