Discussed in this essay:

Swing Time, by Zadie Smith. Penguin Press. 464 pages. $27.

A friendship is the fulcrum of Swing Time, Zadie Smith’s roving and capacious new novel. The unnamed narrator and Tracey, two girls whose “shade of brown was exactly the same,” barely speak to each other when they first meet at a Saturday-morning dance class in 1982 near their council flats in North London. But immediately the narrator feels “this mutual awareness, an invisible band strung between us, connecting us and preventing us from straying too deeply into relations with others.” As the two half-black girls in their dance class, they giggle and joke with the white girls who “had every right to assume that they were our focus, our central concern,” but during break time, the narrator recalls, “Tracey and I lined up next to each other, every time, it was almost unconscious, two iron filings drawn to a magnet.”

The intensity of the girls’ friendship has as much to do with the differences between their families as it does with what they share. The narrator’s politically minded, Jamaican-born mother — “a woman plotting an escape, from me, from the very roles of motherhood” — would rather read Marxist tracts than play with her daughter, and she disapproves of Tracey’s mother, a white woman who is raising the girl on her own. Still, the narrator finds comfort in her friend’s home, where “despite my mother’s constant implication that Tracey’s mother was slovenly, a magnet for chaos, I found her kitchen both cleaner and more orderly than ours.” The narrator’s mother, with her high-minded ideas about food, can’t spend fifteen minutes in the kitchen

without being reduced to a sort of self-pitying mania, and quite often the whole misguided experiment (to make vegetarian lasagne, to do “something” with okra) became so torturous for everybody that she would manufacture a row and storm off, shouting. We would end up eating Findus Crispy Pancakes again. Round Tracey’s things were simpler: you began with the clear intention of making Findus Crispy Pancakes or pizza (from frozen) or sausages and chips, and it was all delicious and no one shouted about it.

The narrator is also aware that Tracey is the natural ballerina, her feet “like two hummingbirds in flight,” whereas the narrator is a better singer than a dancer, her flat feet relegated to tap. Their friendship revolves around dance: they watch musicals together, make up melodramatic stories about ballerinas “in various forms of physical danger,” and are enthralled when they see Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” video, marveling at his red leather outfit as “we jerked our zombie bodies.”

As time goes by and the girls drift apart, their friendship recedes into the background of the novel. Tracey becomes a professional dancer; the narrator briefly works for a music-video channel before landing a job as the personal assistant to a Madonna-like pop star named Aimee, who replaces Tracey as the focus of the narrator’s concern. Years pass without any contact between Tracey and the chameleon-like narrator, who takes on the cosmopolitan lifestyle of her boss, shuttling by private jet between London, New York, and, eventually, a village in an unnamed country in West Africa, where Aimee opens an “empowering school for girls” and, as you might expect, adopts a child.

This may sound like the stuff of bad satire, but Smith is less interested in the contemporary cult of celebrity than in the ripple effects of such power on the lives it touches. “Everybody’s path crossed with hers at the same moment,” the narrator says of Aimee, and the novel moves back and forth in time in order to convey the narrator’s attempt to make sense of it all. Aimee’s impact on her life began long before they first met, when she and Tracey brought her debut single to the tenth-birthday party of a playmate, a white girl named Lily Bingham, who lived in a “whole house” with a garden. Decades later, a video of the two brown girls from the council flats dancing to the song, dressed in lacy camisoles taken from Mrs. Bingham’s lingerie drawer, is uploaded to the internet and becomes part of a vicious public shaming.

That such a video would be quite so humiliating — some consider it “borderline child pornography” — might seem dubious; surely one of the legacies of a go-girl phenomenon like Aimee would be to render mildly risqué dance routines unexceptional. Then again, the narrator grew up being told that certain permissions granted to middle-class white girls didn’t apply to her. She and Tracey arrive at Lily’s birthday party in fancy attire; the white girls are wearing pinafores and dungarees, and Mrs. Bingham “looked almost homeless, her hair barely brushed.” When the narrator’s mother is told about the impromptu dance show, her reaction makes clear that they have breached more than birthday-party etiquette. “You think you’re one of them?” she shouts. “Is that what you think?” A couple of years later, when the narrator is on the cusp of adolescence, her mother tells her that dancing is a dead end:

“What happens with this” — she gestured at my body — “that will never matter, not in this culture, not for these people, so all you’re doing is playing their game by their rules, and if you play that game, I promise you, you’ll end up a shade of yourself. Catch a load of babies, never leave the streets, and be another one of these sisters who might as well not exist.”

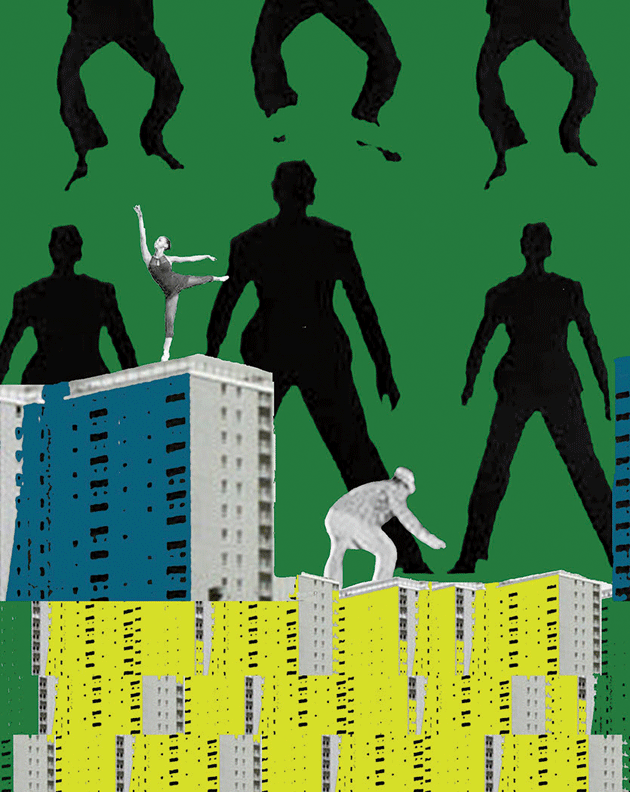

There is something mournful about this admonition, which comes at the midpoint of the novel, long after we learn that, for the narrator, dance represents an ideal form of freedom — an ability to live decisively, in the moment, outside the exigencies of passing time. When we first meet her, she is back in North London after being fired by Aimee (the reasons become clear later). One afternoon, she drops in on a talk by an Austrian film director. He projects a video that the narrator remembers vividly from her childhood: a scene from the 1936 musical Swing Time, in which Fred Astaire tap-dances in front of three silhouettes who struggle to keep up with him. The director drones on about “pure cinema” and the “interplay of light and dark,” but the narrator finds that the clip exerts a more immediate power. “I’d lost my job, a certain version of my life, my privacy,” she says, “yet all these things felt small and petty next to this joyful sense I had watching the dance, and following the precise rhythms in my own body.”

As lovely as this sentence is, Smith is flirting here with sentimentality; at such moments, dance risks becoming the ultimate embodiment of, well, embodiment — a convenient counterpoint to abstraction and artifice, as well as the political ideas brandished by the narrator’s mother. But Smith is too subtle a writer to leave it at that. Returning to her flat, the narrator pulls up the Fred Astaire clip on her laptop and realizes that she is looking at a white man in blackface. “I had managed to block the childhood image from my memory,” she admits. “The rolling eyes, the white gloves, the Bojangles grin.”

In Swing Time, dance is not simply a visceral experience of movement and joy; it is also an activity that is mediated — often watched rather than done — and commodified. As a child, the narrator had ignored the hokey plots and stereotypes of the big-budget musicals, with their “minstrels, maids and butlers.” For her, “a dancer was a man from nowhere, without parents or siblings, without a nation or people, without obligations of any kind.” She and Tracey became mildly obsessed with the dancer and actor Jeni LeGon, whom Tracey physically resembles, after watching her in the 1937 musical Ali Baba Goes to Town. Only as an adult does the narrator realize how naïve she’d been about LeGon’s actual life. She had imagined all sorts of friendships between her and the people with whom she worked, including Astaire, when in fact he never spoke to LeGon, considering her tantamount to the maids she portrayed. Even the French-sounding name, so glamorous to two little girls in North London, was a fiction: Jennie Ligon, the Chicago-born descendant of sharecroppers, became Jeni LeGon because of a typo in a gossip column.

The narrator realizes that the dancer they had imagined “was not really a person at all, that was only a shadow.” Shadows, both literal and figurative, are everywhere in Swing Time. The narrator, thinking about LeGon while seated at a café in Paris, sees that her “own shadow was huge and knife-like under the table.” She is still working for Aimee at the time, and only after losing her job does she realize “that I had always tried to attach myself to the light of other people, that I never had any light of my own. I experienced myself as a kind of shadow.”

In college, the narrator is granted a temporary reprieve from her unstable sense of identity by her boyfriend, Rakim, who holds that “all the male sons of Africa were Gods” and speaks with an ardent certainty that she initially finds appealing. He scolds her for her love of musicals and her femininity, deeming it to be of the “wrong kind,” since she has little interest in domesticity. He traces all her flaws to the blood of her white father, running through her “like a poison.” The narrator eventually comes to find his preoccupations stifling, tediously binary:

Why did he think it so important for me to know that Beethoven dedicated a sonata to a mulatto violinist, or that Shakespeare’s dark lady really was dark, or that Queen Victoria had deigned to raise a child of Africa, “bright as any white girl”? I did not want to rely on each European fact having its African shadow, as if without the scaffolding of the European fact everything African might turn to dust in my hands. It gave me no pleasure to see that sweet-faced girl dressed like one of Victoria’s own children, frozen in a formal photograph, with a new kind of cord around her neck. I always wanted life — movement.

Movement, dance, a refusal to stand still: Swing Time is in large part the story of the narrator’s resistance to being pinned down, whether to family or to relationships or to a fixed idea of who she is. She chafes at Rakim’s attempts to “educate” her not because she subscribes to bland liberal fantasies about transcending race but because his doctrinaire theories are incommensurate with her experience as the daughter of a black mother and a white father. Yet his adamant essentialism turns out, like Rakim himself, to be more complicated than it first appears. At graduation, a couple of years after she has broken up with him, the narrator learns that his mother is white.

Smith, herself the daughter of a black mother and a white father, has written of how

when your personal multiplicity is printed on your face [you] have no choice but to cross borders and speak in tongues. That’s how you get from your mother to your father, from talking to one set of folks who think you’re not black enough to another who figure you insufficiently white.

Rakim and the narrator show there are various ways of crossing those borders — or choosing not to. Rakim, so determined to deny a part of his identity, is in danger of losing himself to his commitments. The narrator, by contrast, is in danger of losing herself to her multiplicity: so full of negative capability, without any clear commitments of her own.

Smith makes brilliant use of the narrator’s subjectivity, deploying her shifting sense of self to keep Swing Time on its toes, oscillating between individual lives and the larger forces that bind and shape them. During a visit to a London museum, the narrator tells Aimee the story of the Zong, an eighteenth-century slave ship that set sail for Jamaica and, after a navigational error, began to veer off course. Water supplies dwindled. Thinking of the bottom line, the captain devised a plan: if he disposed of some of his cargo, the loss would be covered by insurance. And so, in the narrator’s telling, the crew took 133 men, women, and children and tossed them, still shackled, into the sea. Ultimately, the insurer refused to pay, and a British judge found in his favor, but only on the principle that the captain had made a navigational mistake. “Those thrashing bodies were still cargo, you could still jettison cargo to protect the rest of your cargo,” the narrator says. “You just couldn’t be reimbursed for it.”

Frustrated with the sentimental readings of history peddled by the museum, she tells this story to convince Aimee that the slave trade was not a series of individual tragedies but a brutal system that rendered human beings into merchandise. The singer is immune to this line of thinking. “Whatever doesn’t kill you makes you stronger,” she says. “If my dad hadn’t died young? No way I’d be here. It’s the pain. Jews, gays, women, blacks — the bloody Irish. That’s our secret fucking strength.”

The author of White Teeth (2000) and The Autograph Man (2002) might have been content to lampoon Aimee as an exemplar of therapy culture, or neoliberal individualism, or the blithe obliviousness of white privilege. That Smith evokes these things without ever reducing Aimee to them is a testament to how far her fiction has evolved since those early books. Aimee — who believes that differences between people are “never structural or economic but always essentially differences of personality” — may be a poor student of history, but Smith also endows her with real, if selective, powers of observation and intuition. She calls the narrator’s bluff when they meet by plucking out the latter’s fake nose ring; later, she accurately diagnoses the mix of priggishness and credulity that has ruined so many of the narrator’s relationships. We also learn that Aimee suffered her own traumas as a child and had to claw her way out of her small Australian hometown; her narcissism comes to look like a vestigial survival mechanism.

White Teeth, published when Smith was only twenty-four, labors under the influence of novelists such as Don DeLillo and David Foster Wallace, whose preoccupation with elaborate systems — capitalism, ideology — sometimes comes at the expense of psychological depth. Smith made a similar trade-off: White Teeth traces a dazzling web of social connections, but the people enmeshed in it often feel less like human beings than signifying machines. “It’s not [the novelist’s] job to tell us how somebody felt about something,” she said in a 2001 interview. “It’s to tell us how the world works.”

Compare that imperative with a comment she made in 2012, shortly after the appearance of her fourth novel, NW, which examines the divergent lives of four characters from the same working-class housing estate in North London. “I don’t feel I know much about the world anymore,” she said. “But I do feel I know myself a bit better.” The book marked a break not only from White Teeth and The Autograph Man but also from her third novel, On Beauty (2005), a placid campus comedy framed as a homage to E. M. Forster’s Howards End. In getting to know herself better, NW seemed to announce, Smith was also beginning to trust herself more. She no longer felt the need to imitate other writers or to cater to her audience’s expectations. The novel’s fragmented prose explores human subjectivity and contingency with the confidence that, paradoxically, such an exploration demands.

Swing Time represents a further step on this continuum. Her first novel to be narrated in the first person, the book dispenses with the safety and remove of authorial omniscience; gone is the urge to nudge the reader with barbed comments as to what her unwitting characters are really up to. Like Christian Marclay’s The Clock, a twenty-four-hour video montage that Smith praised in a 2011 essay, Swing Time takes shape through jump cuts and collation, swinging from time to time and place to place, and picking up resonances along the way. Soon after her visit to the museum with Aimee, the narrator remembers Lily Bingham, her old playmate, who once took offense when she was shown a musical with an all-black cast. Lily had insisted that race was unimportant, “for, as she solemnly explained to me one day as we played, she herself was ‘color blind’ and saw only what was in a person’s heart.” The juxtaposition of these two episodes suggests a connection without announcing it; the reader is left to infer that, perhaps, one moment of invisibility has recalled another. Like NW, whose narrative shards made it more susceptible to interpretation than Smith’s earlier books, and the richer for it, Swing Time opens up the text by limiting the novel’s perspective. Smith’s command as a novelist resides in her willingness to cede control.

By paying such close attention to others, the narrator develops a keen understanding of power and its circuitous ways. Aimee, who is able to hire and fire on a whim, build a school in a country she knows little about, and adopt a child under questionable circumstances, has “no abstract interest in power” and sees poverty only as “one of the world’s sloppy errors . . . which might easily be corrected if only people would bring to the problem the focus she brought to everything.”

For isn’t the great privilege of power the ability to operate as if it didn’t exist? To adhere, say, to the “neutral universal” school of literary criticism (as Smith herself described it in an essay on Zora Neale Hurston), in which “white novelists are not white novelists but simply ‘novelists,’ and white characters are not white characters but simply ‘human’ ”? As much as we associate power with the exercise of brute force, it more commonly enables a kind of innocence; the powerful aren’t required, as others are, to abide much reality. Even the narrator, in certain contexts, is exempted from the demands of the real world. At one point, while staying in the West African village, she pours a liter of water down the drop toilet to flush out a cockroach, without thinking how far someone had to walk to collect it. She spends money on meals that seem cheap to her but exorbitant to the locals. “Maybe luxury is the easiest matrix to pass through,” she says. “Maybe nothing is easier to get used to than money.”

And maybe nothing is more disruptive to balances of power than love and desire. When a triangle forms between Aimee, the narrator, and a local teacher named Lamin, the pop star lashes out by firing the narrator and rescinding the British visa she promised Lamin. The narrator, in turn, shares some compromising documents about Aimee’s adoption with a gossip website. Meanwhile, Tracey, with three children and nothing left of her dance career, begins to send hateful emails to the narrator’s mother, now a member of Parliament, accusing her of neglecting the problems faced by black people. After many years without contact, the narrator visits Tracey to ask her to stop harassing her mother, but her old friend is unmoved. “There can’t be no understanding between you and me anymore!” Tracey says. “You’re part of a different system now. People like you think you can control everything. But you can’t control me!”

Who holds the power here? Is it the narrator’s mother, a politician whom Tracey regularly sees on TV? Is it the rootless narrator, who has spent her twenties jet-setting between continents, insulated from material want yet envious of Tracey’s talent and children? Is it Tracey, a single mother who still lives in the council flat where she grew up? She, after all, is the one who responds to the narrator’s visit by uploading the embarrassing video from Lily Bingham’s party, telling the narrator that her true self has finally been exposed. Smith seems to be suggesting that power is fluid, especially in the internet era, when “everything you need to burn somebody’s house down . . . is already in your hand.” But she knows better than to declare a false equivalence. Only Aimee has the means to upend people’s lives by taking away the material conditions necessary to sustain them. Her bubble is a fortress.

This is how real power works, able to withstand the occasional jolt to the system. Faced with such an impasse, it is tempting to say that what’s needed is more empathy. But Aimee is hardly deficient in this respect; the narrator observes her talent for connecting with others on their own terms, engaging even the dying “in their present situation, without nostalgia or false optimism.” Literary types are inclined to sentimentalize empathy and often speak as though it were a cure-all for the world’s ills, but in Swing Time Smith shows how swiftly it can be pushed aside by competing loyalties and ambitions. The narrator says that she never lost sight of Tracey — “I was her only witness, the only person who knows all that she has in her, all that’s been ignored and wasted” — but acknowledges that she allowed their friendship to wither: “I still left her back there, in the ranks of the unwitnessed, where you have to scream to get heard.”

“Everybody had tried their best within the limits of being themselves,” the narrator assures her mother near the end of the novel. Smith is ever mindful of these limits — not only the walls of the self but the larger barriers of those entrenched systems that are, by definition, impervious to any one person’s conscience or will. Swing Time is full of truths that are at once generous and stripped of illusion. Despite her claims to the contrary, Smith still knows a thing or two about how the world works.