We’re somewhere around Wautoma, in central Wisconsin, when it starts to take hold: my father and I are finally going to a Green Bay Packers game. It’s the morning after the third presidential debate. make america great again signs stand in front of houses that could fit comfortably inside a two-bedroom unit at Trump Tower. The very pinewoods and cornfields seem to declare their allegiance to the G.O.P. ticket. The only signs for Hillary suggest that she should be in prison. One shocks us with its crudity: trump that bitch. But we laugh, thinking how a simple comma would change its meaning entirely.

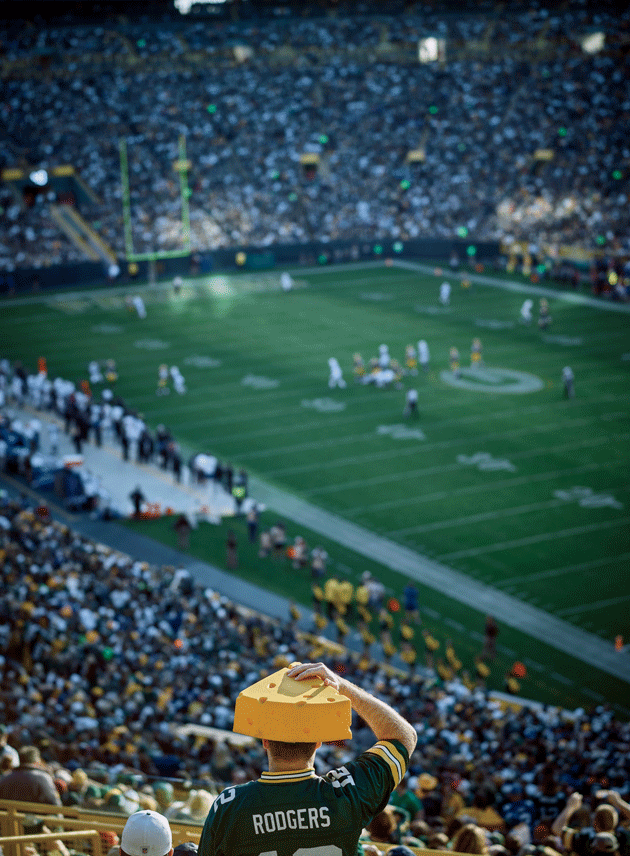

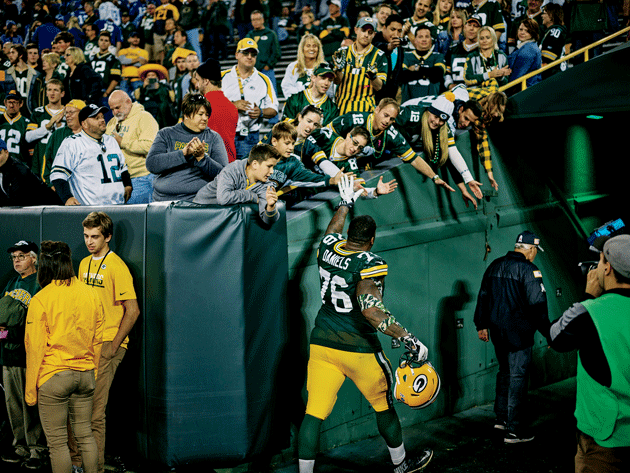

Photographs of the football game between the Green Bay Packers and the Indianapolis Colts, and fans outside Lambeau Field, November 6, 2016, Green Bay, Wisconsin, by Balazs Gardi

More significant to us this morning, however, are other signs, which tell us that we’re nearing Lambeau Field, long a kind of secular Mecca for my family. In Lodi, where we stop for coffee, the flattened G of the team’s logo hangs among the unlit neon signs in a liquor-store window. A bulging leaf bag designed to look like a Packers helmet sits in the middle of a raked yard. The guy stocking shelves at Walgreens is wearing a Jermichael Finley jersey — never mind that Finley hasn’t played since suffering a bruised spinal cord on this exact date three years ago. Back in the car, passing the exit for Portage, I get the sense that even the prisoners in Columbia Correctional Institution, where Jeffrey Dahmer was incarcerated, will be watching the game tonight.

When we pass an Amish farmer in a horse-drawn cart on the highway shoulder, I say, “I bet he’s the only person we’ve seen who won’t be watching the game.”

“That’s why I could never be Amish,” my father says.

I flew home for this game. I live in California now, where I find it difficult to explain to friends my family’s love for the Packers, and for football in general. During my childhood, we lived in Freeport, Illinois — but we were dairy farmers, which made us honorary Wisconsinites. Later on, after I had already left home, my parents made it official by moving to a small farm outside Madison.

In the early Nineties, the great Packers linebacker Ray Nitschke, renowned for his brutal tackles, came to the Ford dealership in Freeport to sign autographs. My brothers and I approached him with trepidation. Though he had retired before we were born, I remember being afraid that he would shake off his age and arthritis, the way rockets shake off ice as they leave the launching pad, and demand something brave of us. Instead he remained in his seat. Actually, there was something about him that reminded me of my grandfather at the end, crippled from decades of farming, his fingers bent at right angles at the first knuckle. I had brought my treasured copy of Steve Cameron’s The Packers! Seventy-five Seasons of Memories and Mystique in Green Bay, and Nitschke scrawled his name in glossy marker across a black-and-white photograph of himself running down a tunnel, the 66 on his jersey hovering apocalyptically in the distance. The spine of that same book cracked the other night when I opened it to refresh my memory of Packers history. (May I be forgiven for having forgotten so much!)

The Packers were founded in 1919. Curly Lambeau, a football standout in college at Notre Dame, and George W. Calhoun, the sports editor of the Green Bay Press-Gazette, decided to start a team in the little town. It was not such a strange proposition at the time, when similarly small towns such as Sheboygan and Oshkosh had their own football teams. Lambeau worked as a shipping clerk at the Indian Packing Company — hence the name of the new franchise. His boss paid for jerseys and offered the use of a field next to the plant several days a week.

The Packers were founded in 1919. Curly Lambeau, a football standout in college at Notre Dame, and George W. Calhoun, the sports editor of the Green Bay Press-Gazette, decided to start a team in the little town. It was not such a strange proposition at the time, when similarly small towns such as Sheboygan and Oshkosh had their own football teams. Lambeau worked as a shipping clerk at the Indian Packing Company — hence the name of the new franchise. His boss paid for jerseys and offered the use of a field next to the plant several days a week.

In the old pictures, the men that Lambeau found to play for him look like soldiers, or smoke jumpers, or any other outfit of rakish young men. Their names conjure another era of American sport and masculinity. There was Red Dunn and Whitey Woodin, Cub Buck and Moose Gardner, Dick O’Donnell and Harry O’Boyle. There was Jug Earp, who was related to Wyatt, and there was Johnny “Blood” McNally, who plucked his sobriquet off a theater marquee advertising Rudolph Valentino’s Blood and Sand, and who had already tested his mettle playing for such vanished franchises as the Milwaukee Badgers and the Duluth Eskimos.

They must all be dead now, those boys who (to paraphrase the poet James Wright) grew suicidally beautiful in October and galloped terribly against one another’s bodies — and did so without much protective gear. In its early years, football more closely resembled rugby than the game we know today. The helmets were really just leather caps like those worn by early aviators. In a photograph from as late as 1928, a Green Bay tailback named Eddie Kotal is playing bareheaded.

The Packers won ten games that first year, besting the Marinette Northerners, the Racine Iroquois, and the Stambaugh Miners — losing only one game, the last of the season, to the Beloit Fairies. The players split the profits, which amounted to sixteen dollars apiece. Some of that money had come out of Calhoun’s hat, which was passed around the sidelines during games like a collection plate. (The median annual salary for an NFL player today is around $860,000.) But the Packers suffered financial hardships in those years, requiring more cash than could realistically fit in a hat. Lambeau scratched around for funds, and supposedly a friend sold his car early on to keep the team solvent. In the end, aid came mostly in the form of stock sales, the first of which took place in 1923: the team sold a thousand shares in the Green Bay Football Corporation at $5 each, and further required shareholders to buy six season tickets, hoping to fill the bleachers and the coffers in a single go.

Today the Packers are the only professional sports team in the United States that is owned by shareholders — 363,948 of them, representing 5,020,523 shares. This is one of the main reasons why such a small town has managed to retain a professional franchise. The other is that the Packers seem inexorably entwined with this place, its weather, and its residents. Which explains in turn the airborne communion of the Lambeau Leap: when a Packer scores a touchdown, it is expected that he will jump into the stands. In this way, the symbolic embrace of the team is made literal, even more so if the player happens to weigh 340 pounds, like the great nose tackle Gilbert Brown.

The cheesehead is another symbol of this intense connection. Donning a wedge-shaped foam crown, fans can simultaneously celebrate the team and the state’s signature commodity. (The Packers sell their own version for $19.95, available in just one color: gold.) To be honest, my family has never owned a cheesehead, being as we are from the milk side of the spectrum. But there are other options when it comes to what to wear to a game. Squint your eyes, and the crowd at Lambeau sometimes resembles the Wisconsin woods: through an understory of camouflage fabric, you can see both hunters in their blaze orange and innumerable animals in the form of fur hats and mittens. (In the woods at Lambeau, you will also find a few naked, shivering men.)

Before leaving the house this morning, I texted my brother Levi to ask if I could wear his blaze-orange hunting coat, it being a night game, with temperatures expected to be in the low thirties. Permission was granted. As for my hands, I will be wearing the same cheap farm gloves I wore to feed calves as a boy.

I remember gray Sundays, sitting on the floor of the living room, holding a Packers football and gazing up at the TV in rapt anticipation. In those days, there was no NFL Network with its 24/7 coverage. No scrolling tweets from fans, no fantasy-football stats, no chanting crowds holding up signs behind chuckling pundits. From the primordial buzz of some commercial would appear a sudden aerial shot of Lambeau Field, which I could sense was somewhere to the north and east of us, just as you sense a mountain at night. If it was a noon game, my father would be sitting on the couch behind me. If it was a three o’clock game, he would already be back over the hill, where the main farm was, milking cows and listening to the Packers on the manure-speckled parlor radio. I used to feel guilty for being able to watch the game while he had to listen to it. Now I think it must have been beautiful, imagining the plays the way one imagines scenes in a novel.

At halftime, if he was home, we’d head out to the yard and he would kick high and sometimes errant punts that we would field and run back while he feigned tackling us. The radio would be on, the speakers pointed to blare through the window screens, the familiar voices of Jim Irwin and Max McGee analyzing how the Packers had played in the first half and what they would have to do in the second to win.

At halftime, if he was home, we’d head out to the yard and he would kick high and sometimes errant punts that we would field and run back while he feigned tackling us. The radio would be on, the speakers pointed to blare through the window screens, the familiar voices of Jim Irwin and Max McGee analyzing how the Packers had played in the first half and what they would have to do in the second to win.

In those years, the Packers lost many more games than they won. It was a discouraging stretch. Between 1986 (when I was four years old and probably just becoming a conscious Packers fan) and 1991, the team won thirty-three games, lost sixty-one, and never made the playoffs. Their coach in that era was Lindy Infante. My brothers and I heard the name as “Lindy and Fante,” and couldn’t figure out how the Packers could be doing so badly with two coaches when the teams that were beating us had only one. I imagined Lindy and Fante as a kind of Dumb and Dumber duo, calling nonsensical plays that confused our team, producing one disaster after another on the field. But when I went outside after a game and acted out incredible catches broken by piles of leaves, the players I pretended to be were perfect and victorious.

I never doubted that I would be a great football player myself. How could it be otherwise? I loved the game so much and knew everything about it, down to its most obscure rules. This is why it was so shocking to me when, at my initial practice for Junior Tackle, I took my first hit. It couldn’t have been a very hard hit, considering we were in fifth grade, but it rattled me enough to bring tears to my eyes. Luckily my helmet and face mask prevented anyone from noticing. Still, I knew immediately that what I had imagined football to be was not what it was.

What followed were years of me trying to be something I wasn’t physically, and perhaps emotionally, capable of being: a good football player. I was small, tentative, slow, and weak. I must have been delicious to hit, like a wounded gazelle separated from the herd. It helped when, in 1993, Rudy came out. I took the movie as my inspiration. Like the protagonist — whose real-life model, Daniel “Rudy” Ruettiger, was even smaller than I was — I would be the kid whose love of football and his ability to play it diverged so widely that only determination could close the gap. There must have been boys like me all over America, boys who had seen the movie so many times they could quote entire scenes.

Unlike Rudy, I was never triumphantly carried off the field on the shoulders of my teammates. Instead I did the scrub work, volunteering to haul the netted bags full of footballs from the bus to the field and back to the bus again in order to feel like I was contributing something. I was a superfluous presence, just like Brian Meyers, a pale, gangly kid whose football career ended the day that Shawn Bradbury, who would go on to catch a game-winning Hail Mary in high school, called out before practice, “It’s Brian’s birthday!” Everyone piled on top of him, myself included. The snap we heard was his arm breaking. Turned out it wasn’t even his birthday.

I spent most of my time in the training room, not because I was hurt but because the ritual of getting my ankles taped seemed to promise at least some minimal opportunity to twist them. I also liked the old trainer, Coach Chance. He treated all of us the same, maybe because he didn’t know who was starting and who was warming the bench, but I think there were other reasons too. He seemed to understand that everything would even out someday — that on or off the football field, the last would be first, and the first last.

As for the actual coaches, I didn’t like them very much. One was always screaming that we had to be the meanest sons of bitches in the valley. I took this to refer to the Pecatonica River Valley, but I think he meant some other, more metaphysical location. They yelled at us when we hit the blocking sled, just as the coaches did in Rudy, and they yelled at us in the chutes, where we were set against one another like dogs. I would get crushed in there, my mind gone star-white from the helmet-to-helmet hit, but still I’d come running out, yelling, my face mask clotted with mud and grass, hungering for a pat on the head from a coach who was probably just pitying me.

My only moment of glory as a football player was, characteristically, witnessed by almost nobody. During my sophomore year I somehow managed to get into a game against the Guilford Vikings. Maybe someone had been hurt, or maybe we were getting beaten so badly that the coach cleared the bench. I was playing cornerback, praying that the play wouldn’t come toward me. At the snap, that’s exactly what started to happen — but it was a reverse. As the play shifted to the other side of the field, the Guilford tight end was caught unawares, and turned right into me as I hit him. He went down hard, in what the bellowing coaches would have called a decleating. I stood over him just like Ray Nitschke in one of those iconic photographs, in which he seems to be daring some dazed running back to get up off the ground, and a few players on the sidelines went wild for me.

I remember thinking that I would finally be praised by the coaches, but they had been looking the other way, toward the real play. There was still hope, though. On Sunday nights, we always got together at the coach’s house to eat pizza and watch game film. Since I was never on the tape, I was always bored — but the next Sunday would surely be the exception.

I remember thinking that I would finally be praised by the coaches, but they had been looking the other way, toward the real play. There was still hope, though. On Sunday nights, we always got together at the coach’s house to eat pizza and watch game film. Since I was never on the tape, I was always bored — but the next Sunday would surely be the exception.

Wrong again. My brief shining moment had taken place just outside the frame. You could see, if you were looking for it, the Guilford tight end on the ground, but you couldn’t see the preceding hit. It was lost forever. The following summer, I took the advice of an assistant coach who, after watching me repeatedly lap the entire team in a conditioning drill on the track, called me over and said, “Hey, Smitty. Maybe you should run cross-country this fall.”

We know we’ve entered Green Bay when we cross Lombardi Avenue. It’s yet another sign, a literal one, of the cultish devotion this town feels for its team: when a Packers coach wins the Super Bowl, the town names a street after him. There’s Holmgren Way, and Mike McCarthy Way, and quite a number of additional streets named after players, such as Bart Starr Road, Reggie White Way, and Tony Canadeo Run. It’s as if Lambeau Field is a great heart, pumping the myth of the Packers into the arterial roads surrounding the stadium.

We head toward the river and stop at the Titletown Brewing Company for lunch and the first beers of the day. The bar is full of Packers jerseys. It gives the illusion that the players have been cloned to populate the town, though the body types filling the jerseys here are significantly different from those of the players. We eat bowls of bison chili. The beer I’m drinking is called Johnny Blood Red.

We head toward the river and stop at the Titletown Brewing Company for lunch and the first beers of the day. The bar is full of Packers jerseys. It gives the illusion that the players have been cloned to populate the town, though the body types filling the jerseys here are significantly different from those of the players. We eat bowls of bison chili. The beer I’m drinking is called Johnny Blood Red.

After lunch, we drive to the quiet neighborhood where we’ll be spending the night with my friend Kevin’s parents. I had worried that we would be imposing, but Kevin assured me that his parents often allowed Packers fans to crash at their house after a game. “I swear,” he said, “there’ll be people everywhere, passed out on the floor.” (As it happens, we are the only guests for this particular game.) Within minutes of our arrival, Mrs. Fitchett ushers us down to the basement to view the family’s Packers shrine. “Every house has one,” she says. The shrine features dusty bobblehead dolls, autographed photos of former players, and a framed certificate proving that she is one of the team’s 363,948 owners.

She offers to drive us over to the stadium, and in the car, she notes that her family has held season tickets for decades. Until recently, the only way to get such tickets was to inherit them, like a kind of patrimony. They could not be transferred to anybody outside the ticket holder’s immediate family. Nowadays, however, you can put your name on a waiting list — which currently numbers more than 81,000. The wait is estimated to be around thirty years (although a 2011 article in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel supplied a more pessimistic figure of 955 years). Some couples, on having a baby, immediately put the child’s name on the list. And thus Packers fans are born.

Though kickoff is still hours away, a green-and-yellow horde is already shuffling along Holmgren Way. Our hostess drops us off in the shadow of the stadium. I mean that quite literally: after several expansions, Lambeau Field is the fourth-largest facility in the NFL and seats 81,435 fans. The entire population of Green Bay, just for comparison, is 105,207 — a supply-and-demand disparity, you might think, except that the team has sold out every game since 1960.

We have our tickets scanned and then head over to the Hall of Fame, which has also been expanded and renovated since we were last here, when I was thirteen. Like all true fans, we had made an obligatory pilgrimage to Lambeau. There I am in the old photos, bespectacled and bucktoothed, sticking my head through the hole in one of those life-size cutouts of receivers and quarterbacks. It was the off-season. I remember standing at the south end zone and trying to imagine the bleachers filled for a game. I was certain we would never make it to one. It seemed as impossible for me as walking on the moon.

Inside the Hall of Fame, we join a group of respectfully silent fans watching a looping video of Brett Favre. We see game-worn helmets, the yellow paint nicked from hits the consequences of which may still be reverberating in the brains of the players. In a little room of stacked antique televisions, two men who look like they might be brothers sit watching old game footage. One is wearing a Packers jersey, the other a Bears jersey.

There is an entire wing devoted to Vince Lombardi. It makes sense: if Brett Favre was the team’s Christlike redeemer, Lombardi was its Old Testament God, wrathful one moment, compassionate the next, always demanding ardent devotion. Fans pose for photographs while sitting at a replica of Lombardi’s desk. A picture on the wall shows the coach teaching his most famous play, the Packers Sweep, to an audience of worshipful players. (When a fan and local restaurant owner approached him with the idea of building the Hall of Fame in 1966, Lombardi is rumored to have offered a somewhat equivocal blessing: “Don’t screw it up!”)

The coach’s greatest triumph on the field is commemorated in a dark room nearby. There we watch footage of the so-called Ice Bowl, a 1967 victory over the Dallas Cowboys. Factoring in windchill, the temperature that day was forty-eight degrees below zero. To give us a sense of what fans in the stands might have looked like, two bundled-up mannequins sit in replica bleachers, steam billowing from their mouths in a not entirely convincing imitation of frozen breath. On the screen, the Cowboys’ defensive linemen are kicking at the frozen turf to gain traction on what will be the biggest play of their lives — a play they will fail to make. There was actually a heating system under the field, installed at Lombardi’s suggestion, but it had stopped working. Before the game, Lombardi was worried sick: what if people thought he had chosen a defective heating system on purpose, to give the Packers an advantage over a team that was used to playing on lush Texas grass? In the wake of the 2015 Deflategate scandal, his agonies seem both quaint and hugely impressive. No wonder David Maraniss titled his 1999 Lombardi biography When Pride Still Mattered.

The coach’s greatest triumph on the field is commemorated in a dark room nearby. There we watch footage of the so-called Ice Bowl, a 1967 victory over the Dallas Cowboys. Factoring in windchill, the temperature that day was forty-eight degrees below zero. To give us a sense of what fans in the stands might have looked like, two bundled-up mannequins sit in replica bleachers, steam billowing from their mouths in a not entirely convincing imitation of frozen breath. On the screen, the Cowboys’ defensive linemen are kicking at the frozen turf to gain traction on what will be the biggest play of their lives — a play they will fail to make. There was actually a heating system under the field, installed at Lombardi’s suggestion, but it had stopped working. Before the game, Lombardi was worried sick: what if people thought he had chosen a defective heating system on purpose, to give the Packers an advantage over a team that was used to playing on lush Texas grass? In the wake of the 2015 Deflategate scandal, his agonies seem both quaint and hugely impressive. No wonder David Maraniss titled his 1999 Lombardi biography When Pride Still Mattered.

The Hall of Fame makes us even more excited for the game than we were before. I experience a little of that old anticipation I always felt on Sunday mornings during Mass — not for the Eucharist, but for the communion that would come later, when we got home and the game began.

There is still time to kill, however. We leave the stadium. Outside, there are tents set up for Patrick Cudahy (“The Official Bacon of the Green Bay Packers”), Carmex, and various other products. Also, the fans have begun to tailgate. That’s not the right word, really: a tailgate would be far too small a surface for the quantity of food and liquor people have brought, so most are setting up folding tables. I ask one man who looks like he’s stocking a full bar if he’s mixing drinks for sale.

“For personal consumption,” he says cantankerously.

Along with the alcohol, I note the following food items: brats, burgers, deviled eggs, open cans of kraut blackening on charcoal grills, cupcakes with yellow and green sprinkles, cheese in every shape imaginable (cubes, slices, curds), and a whole pork loin with a butcher knife stuck in it. Radio antennae fly the American flag, Packer flags, flags printed with frothing beer mugs, flags announcing the bar is open. A polka band is wending its way through the lot, trailed by fans dancing to “Roll Out the Barrel.” I notice a half-dozen converted ambulances with yellow-and-green paint jobs, one of them bearing the legend titletown tailgating unit. In the back, where the gurney would normally be, they’ve set up a TV. Trump is giving a speech. I stop a moment to read the words scrolling along the bottom of the screen: “I will totally accept the results of this great and historic presidential election — if I win.”

As my dreams of playing football collapsed, the Packers actually started winning. Early in the 1992 season, their longtime quarterback, Don “Majik Man” Majkowski, was injured during a game against the Bengals. I loved Majik Man. A poster of him hung on the wall at the foot of my bed, perpetually poised to throw me the ball (he never did). Replacing him was a twenty-two-year-old kid from small-town Mississippi, a complete nobody. He led Green Bay back to beat the Bengals 24–23, the first of his thirty fourth-quarter comebacks. The reporter who interviewed him after the game called him Brett Fav-rah — but it wasn’t long before we learned how to pronounce his name.

Favre was the savior we had been waiting for. Year after year, we watched him do impossible things in impossible conditions. He was the toughest player since Ray Nitschke. We didn’t know then that he was heavily addicted to painkillers. Still, what made Favre so fun to watch was how he could go from being so bad to being so good, and then back again. We loved him, even after the reports that he had sent nude selfies to a female journalist, and even after he committed the ultimate act of treachery: finishing his career with the Vikings. At times, our devotion to Favre exceeded even our devotion to the Packers. When the team traded him to the New York Jets and bet on a young quarterback named Aaron Rodgers as the future of the franchise, there was a widespread sense of betrayal among fans. Our neighbor certainly felt that way. Indicating his scorn for the team’s management, he said: “They shouldn’t of been mean to Brett.” (Rodgers, though, proved to be a good bet.)

Favre was the savior we had been waiting for. Year after year, we watched him do impossible things in impossible conditions. He was the toughest player since Ray Nitschke. We didn’t know then that he was heavily addicted to painkillers. Still, what made Favre so fun to watch was how he could go from being so bad to being so good, and then back again. We loved him, even after the reports that he had sent nude selfies to a female journalist, and even after he committed the ultimate act of treachery: finishing his career with the Vikings. At times, our devotion to Favre exceeded even our devotion to the Packers. When the team traded him to the New York Jets and bet on a young quarterback named Aaron Rodgers as the future of the franchise, there was a widespread sense of betrayal among fans. Our neighbor certainly felt that way. Indicating his scorn for the team’s management, he said: “They shouldn’t of been mean to Brett.” (Rodgers, though, proved to be a good bet.)

It was exciting to watch the Packers do some winning after all those years of losing under Lindy and Fante. In 1996, they beat the Patriots in Super Bowl XXXI, bringing the Lombardi Trophy back to Green Bay, where it belonged, for the first time in almost three decades. “Well, we won it, bud,” my father said — and we both recognized the feeling of anticlimax. Our prayers had finally been answered, and we didn’t quite know what to do with ourselves. Now I see that it was all about the longing: that was what we loved. From the moment the confetti started falling from the rafters of the Superdome, I have never been able to care as much about whether the Packers won or lost.

I still watch the Packers whenever possible, if I can find a bar that has the game on. The broadcasts start early on the West Coast, and it takes some effort to sit in a bar at ten in the morning, watching a team I care about less and less, especially as I lose track of who’s on the roster. Often I bring a book to read through the endless commercial breaks, and sometimes I forget about the game entirely: the sound isn’t even on to remind me that something exciting is happening on the field.

It’s becoming harder to justify these solitary bouts of football-watching, and not only because I feel that I’m wasting a Sunday that could be spent in the ocean or the mountains. There is also the long-term physical damage sustained by the players. It was in 2002 that Bennet Omalu, a forensic pathologist performing an autopsy on a former Pittsburgh Steelers player, stumbled across evidence linking the sport to chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Since then, his findings have been widely disseminated, thanks in no small part to Concussion, a 2015 film in which Will Smith plays the heroic doctor. Apparently I’m not the only fan to be troubled by the connection. In October, the New York Times ran an article about the declining viewership of NFL games — which had dropped 12 percent over the first seven weeks of the 2016 season — and many readers were quick to suggest that the concussion issue was a key factor.

In the same comment thread, I found fans practically piling on top of one another to declare why they were abandoning the game. Some bemoaned that football now seemed more player-centric than team-centric. Free agency has made it rare for any player to remain with the same franchise throughout his career, and the increasingly popular phenomenon of fantasy football puts more emphasis on individual stats than group performance. Along with this comes the constant threat that an organization may leave town for a larger media market, an outcome that can be avoided only by the construction of a lavish, taxpayer-funded stadium — i.e., civic blackmail.

In the same comment thread, I found fans practically piling on top of one another to declare why they were abandoning the game. Some bemoaned that football now seemed more player-centric than team-centric. Free agency has made it rare for any player to remain with the same franchise throughout his career, and the increasingly popular phenomenon of fantasy football puts more emphasis on individual stats than group performance. Along with this comes the constant threat that an organization may leave town for a larger media market, an outcome that can be avoided only by the construction of a lavish, taxpayer-funded stadium — i.e., civic blackmail.

Some commenters pointed to changes in the game itself, including the advent of radio communication between quarterbacks and coaches, which robbed players of the sort of spontaneity that Bart Starr displayed so memorably at the Ice Bowl: when he kept the ball, nobody knew what he was about to do with it, not even that omniscient deity Vince Lombardi. Other fans complained about the overuse of instant replay. Why not allow viewers to enjoy the fluid progression of a drive, instead of subjecting them to the same play over and over, sometimes zoomed in ridiculously on a player’s foot? One disgruntled commenter noted that although the average NFL game lasts three hours and twelve minutes, the ball is in play for only eleven minutes. Thanks to DVR technology, of course, it’s possible to skip all the commercials and commentary and interstitial stuffing, at least after the fact. But I find something sad about not seeing the game in real time. At that point, why not just turn on SportsCenter and watch the highlights?

Others addressed off-the-field issues. There was anger over the mild punishments meted out to players caught abusing their spouses on camera. There was even more anger about Colin Kaepernick and his decision to kneel during the national anthem as an expression of solidarity with Black Lives Matter protesters. These comments generated replies, and the replies generated more replies, creating a microcosm of tensions that said more about the state of race relations in America today than the state of football.

My favorite comment, however, blamed the decline in viewership on the following factors: Brexit, the election, lack of jobs, economic stagnation, Wall Street, and war. (For what it’s worth, NFL executives have blamed the presidential election for poor ratings — and indeed, maybe CNN has satisfied our hunger to watch two bruised and bruising opponents go head to head.)

And yet almost every Sunday (or Monday night, or Thursday night), I look for a bar playing the Packers game. Since we live in separate time zones and are separated by thousands of miles, watching the Packers is one of the primary ways my father and I keep in touch. “Love does not consist of gazing at each other,” Antoine de Saint-Exupéry once wrote, “but in looking outward together in the same direction.” He wasn’t talking about football, but the Packers still give my father and me something to focus on together, as problematic as the sport itself is becoming. Watching the Packers is also the way I stay connected to the Midwest. When the camera pans over Lambeau Field, full of fans obscured by their own breath, I remember the feeling of fall back home, and can almost imagine that I’m a boy again, sitting on the floor of the living room, waiting for the game to begin.

We enter the stadium just before dark, the lights burning under the gray sky. As big as Lambeau is, I remark how the field has remained the same: still one hundred yards of turf, just like the one I played on as a fifth grader. Everything around us — the vast stadium with its box seats, the planned $140.5 million expansion of the Atrium, the tailgating and the dancing girls, the trailers for the TV networks with their fishbone antennae — all of it has grown around the fact of this field like the pearl that grows around a grain of sand.

We’re early enough to walk right down to the front row, where we watch a dozen Packers jog out of the tunnel to warm up. They look small without their pads. Aaron Rodgers throws passes to Jordy Nelson, and they could be high-school kids tossing the ball around before a Friday-night game.

We go up to our seats and feel the stadium fill. I notice that I’m practically the only fan wearing blaze orange, which confuses me until I realize that blaze orange is very close to Bears orange. My dad looks like a Bears fan, too, wearing a black-and-orange Freeport Pretzels (yes, that was my high-school team) pullover. As for the Packers themselves, they surprise us by running out of the tunnel in white instead of the classic green and gold — a marketing decision, most likely, meant to boost jersey sales.

We go up to our seats and feel the stadium fill. I notice that I’m practically the only fan wearing blaze orange, which confuses me until I realize that blaze orange is very close to Bears orange. My dad looks like a Bears fan, too, wearing a black-and-orange Freeport Pretzels (yes, that was my high-school team) pullover. As for the Packers themselves, they surprise us by running out of the tunnel in white instead of the classic green and gold — a marketing decision, most likely, meant to boost jersey sales.

Just before kickoff, two fans come down to the field to participate in a challenge. If they can catch a football launched from a cannon, they stand to win a new snowblower. But both, awkward in helmets, drop the ball. During the national anthem, for which, as far as I can see, no players kneel, a massive American flag is unfolded, and fireworks go off around the perimeter of the stadium. How could the kickoff not be anticlimactic, after the fanfare of the pregame party and the polka band and the pyrotechnics? There is a feeling in the stadium of deceleration. It seems odd that the energy has begun to wane just as the game begins.

Neither team scores a touchdown in the first half. The kickers take turns kicking field goals, and at halftime the Packers are up, 6 to 3. My father and I agree that the halftime performance of the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra is the most dramatic and impressive thing we’ve seen happen on the field. It isn’t that the teams are playing badly. Rather, there’s a kind of blanket smoothness and professionalism to everything that happens, which makes the fans particularly unforgiving when anything goes wrong. At the start of the third quarter, Aaron Rodgers fumbles the ball into the end zone, resulting in the Bears’ only touchdown. The fans around us rise as one to unleash a blast of profanities at a player who has led the Packers to the Super Bowl, and who will almost certainly join the apotheosized names and numbers inscribed around the rim of the stadium.

Between the fumble and the yelling, in fact, it’s easy to overlook how good a game Rodgers is having. He’ll end up completing thirty-nine of fifty-six passes, breaking a team record. But we won’t realize this until the next morning, maybe because, as my father says, everything seems so perfectly scripted, as if the Packers and the Bears, historically the most antagonistic teams in football, are moving as one organism toward a common purpose: to get out of here without suffering any season-wrecking injuries.

The Bears fail in this, as they do in much else tonight. In the second quarter, their starting quarterback, Brian Hoyer, pulls a Brian Meyers and breaks his arm. Their longtime starter, Jay Cutler, is already out with a thumb injury. They bring in the third-string quarterback, Matt Barkley, who will complete only six passes and throw two interceptions. As the game begins to slip away from the Bears, the crowd seems to wake up a bit. At one point our section tries, halfheartedly, to do the wave, but we can’t manage even a ripple.

To be honest, the fans seem much more excited about something that appears on the Jumbotron, a race between animated beer bottles (Miller 64 takes first place). But after this fleeting moment of joviality, things turn dark again. The guy to our left, who looks like he either just got out of Columbia Correctional or is just about to go in, keeps yelling, “You fucktards!” A shanked punt triggers the worst of his ire. In addition to his favorite insult, he unfurls a blistering sequence of profanities that makes us wince for the sweet little boy sitting one row down, Packers tattoos on his cheeks, his father next to him.

To be honest, the fans seem much more excited about something that appears on the Jumbotron, a race between animated beer bottles (Miller 64 takes first place). But after this fleeting moment of joviality, things turn dark again. The guy to our left, who looks like he either just got out of Columbia Correctional or is just about to go in, keeps yelling, “You fucktards!” A shanked punt triggers the worst of his ire. In addition to his favorite insult, he unfurls a blistering sequence of profanities that makes us wince for the sweet little boy sitting one row down, Packers tattoos on his cheeks, his father next to him.

I had thought that when my father and I were finally sitting side by side in the bleachers at Lambeau, I would be as focused on football as I used to be as a boy. But I find my attention keeps wandering. I stare at the spot where Bart Starr snuck into the end zone to win the Ice Bowl. Or I study the names and numbers along the perimeter of the stadium, and think about Nitschke and Hornung playing here. Or I recall those NFC Wild Card games that meant so much to us in the years when the Packers were just getting good, when Favre would bring them down the field in the fourth quarter and we’d say, “He can’t possibly do it again.” And then he would, and when my father walked in for supper, we would compare what I had watched and what he had heard.

I need only close my eyes and it’s a beautiful day in October, in the Lindy and Fante years. The Packers are playing the Bears, and it’s a noon game, so my father can watch most of it. At halftime, we go out to the front yard to run punt returns. He kicks us some woozy punts and nobody calls him a fucktard. The ball hangs in the air and everything is still ahead of me: the first day of Junior Tackle, the hit I’ll make in the Guilford game that no one will see, the confetti falling from the rafters of the Superdome after Super Bowl XXXI, my mounting disillusion with the entire sport. I catch the ball and run toward my father, who’s coming up as if to hit me. Instead he catches me and swings me down laughing into the leaves.