If you were losing your mind, how would you know? What if instead it were the world that was losing its mind — flouting the usual statutes re: time and space? At what point would you look into a darkened window and, failing to see your reflection, say, “It’s not me, it’s you”? Maybe you’d say nothing at all, given that the customary divisions between me and you, mind and matter, had gone null and void, were no longer relevant, had most definitively ceased to apply. In this case the most pressing problem would seem to be not sanity but location — how to find your place in a new mental geography. Such is the conundrum raised in Daniel Kehlmann’s novel, YOU SHOULD HAVE LEFT (Pantheon, $18), translated from the German by Ross Benjamin, when the narrator, his wife, Susanna, and their four-year-old daughter, Esther, take up residence in a mountaintop getaway rented from a mysterious landlord through Airbnb. One of the mordant jokes of this clever, exquisitely terrifying slip of a book: On the internet, nobody knows you’re a ghost.

Untitled photograph from the series Radici © Fabrizio Albertini

The narrator is a screenwriter on deadline, and You Should Have Left unfolds as a diary that blends notes for Besties 2, the script he owes the studio, with events from daily life.

Meanwhile Esther was telling us about a friend from preschool who is named either Lisi or Ilse or Else and either took a toy away from her or gave her one, at which point the teachers did either nothing at all or just the right thing, or something wrong; little kids are not good storytellers. But Susanna and I exclaimed That’s great! and Incredible! and How about that! and the relief when she stopped talking brought us closer together.

The unraveling begins in the dark. Strange intrusions erupt in the diary — the words “Get away” in the middle of a paragraph. The narrator suffers disturbing dreams. A picture appears where none was before. A shopkeeper straight from central casting asks, “Anything happen yet?” Unsettled, the family is about to hit the highway when the narrator looks at Susanna’s phone and discovers that she’s having an affair. A fight ensues and she takes off in the car. Dad and daughter try to walk downhill but the path leads them back to the front door; they’re trapped in the force field of a parallel universe. The flatness of the tone is what scared me the most:

A short while ago there was a man in the room. He didn’t look dangerous, more tired. . . . I think he resembled the woman with the narrowed eyes, but I couldn’t really tell, because he wasn’t standing on the floor but on the ceiling, and he was looking down at me as if he wanted to ask for help. But he was here only briefly, and I’m so exhausted I might also have imagined him.

Like Kehlmann’s other novels, You Should Have Left is smart and brisk. He makes entertainment out of metaphysics and is open to more than the occasional haunting: casual talk of ghosts, comic flights of lunacy, excursions into hypnosis, crises of faith. His characters bring an empirical scrutiny to the otherworldly. In his first novel, Measuring the World, Alexander von Humboldt offers a surveyor’s adage: “Whenever things were frightening, it was a good idea to measure them.” The narrator of You Should Have Left takes this advice literally, by sketching a right triangle with a ruler. But no matter what he does, the angles add up to 172, and a rectangle fares no better. There’s something wrong with the drawings. They make his eyes go fuzzy. By the end, he understands. He’s gone over to another side, or inside; there are more dimensions there, it’s hard to explain. Maybe it’s all an elaborate metaphor for that most quotidian reality, a disintegrating marriage — the angles of one man’s life collapsing as the house caves in.

Another man with a measure, the German cartographer Carsten Niebuhr, rode into Copenhagen in November 1767. He had been traveling for six years. In that time he had charted the transit of Venus; gauged the height of the pyramids at Giza (contemporary accounting has corrected him by only seventy-one centimeters); surveyed Persepolis; and rendered a map of Yemen that explorers would depend on for a century. Niebuhr wrote in his diary about allowing a Turkish merchant to look through the eyepiece of one of his surveying instruments. The merchant “was rather disquieted when he saw a tower standing upside down. This gave rise to a rumor that I had come to Alexandria to overturn the whole city and stand it on its head.”

Niebuhr was the sole survivor of the first European expedition to Arabia Felix, or Happy Arabia, as Yemen was then known — a series of mistranslations had rendered it Eudaimon Arabia, l’Arabie heureuse, das glückliche Arabien. It did not live up to its name. The covey of six traveled by land and by sea, in grand merchants’ caravans and on rickety cargo floats — and they hated one another. Their bold adventures and petty rivalries are chronicled in Thorkild Hansen’s ARABIA FELIX: THE DANISH EXPEDITION, 1761–1767 (New York Review Books, $17.95), first published in 1962. In places, the prose shows its age — “Arabs in the desert are content with small things; they live their lives as they drink their coffee, and are content with a little each time” — but Hansen’s research into the letters, reports, and financial records of the expedition is scrupulous, and his novelistic skill makes for a ripping chronicle. Sponsored by Frederick the Little (“It had become fashionable to support the arts and sciences,” Hansen notes, a sentence lately uttered about our own country by no one), the men were charged with surveying the region’s geography; copying down inscriptions left by the Israelites in the Sinai Desert; collecting flora and fauna; and charting the tides of the Red Sea (to establish a more rational interpretation of the exodus out of Egypt).

Niebuhr was the sole survivor of the first European expedition to Arabia Felix, or Happy Arabia, as Yemen was then known — a series of mistranslations had rendered it Eudaimon Arabia, l’Arabie heureuse, das glückliche Arabien. It did not live up to its name. The covey of six traveled by land and by sea, in grand merchants’ caravans and on rickety cargo floats — and they hated one another. Their bold adventures and petty rivalries are chronicled in Thorkild Hansen’s ARABIA FELIX: THE DANISH EXPEDITION, 1761–1767 (New York Review Books, $17.95), first published in 1962. In places, the prose shows its age — “Arabs in the desert are content with small things; they live their lives as they drink their coffee, and are content with a little each time” — but Hansen’s research into the letters, reports, and financial records of the expedition is scrupulous, and his novelistic skill makes for a ripping chronicle. Sponsored by Frederick the Little (“It had become fashionable to support the arts and sciences,” Hansen notes, a sentence lately uttered about our own country by no one), the men were charged with surveying the region’s geography; copying down inscriptions left by the Israelites in the Sinai Desert; collecting flora and fauna; and charting the tides of the Red Sea (to establish a more rational interpretation of the exodus out of Egypt).

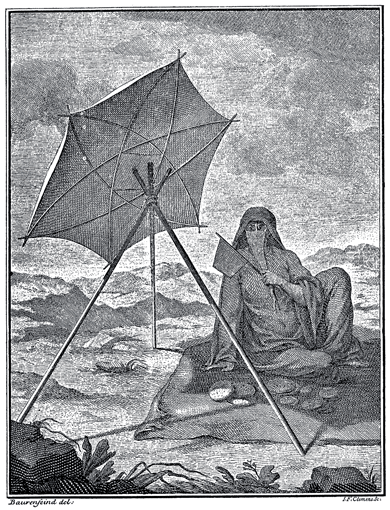

Niebuhr’s companions were Peter Forsskål, a brilliant and conceited botanist; Christian Carl Kramer, a mediocre physician; Georg Wilhelm Baurenfeind, an unremarkable artist; Lars Berggren, the servant; and Friedrich Christian von Haven, an indolent, swindling philologist, whom Hansen makes a passable villain. It’s hard to pinpoint von Haven’s worst offense. Was it his bungling of the foray to Mount Sinai? His failure to procure priceless manuscripts from St. Catherine Monastery? Or his purchase, in Constantinople, of enough white and yellow arsenic to do away with thirty men, which so consternated his fellow explorers that they dispatched letter upon letter home, begging to be released from his company? When malaria struck the expedition, von Haven was the first to waste away, in the seaport of Mocha, a “hell of heat and humid air.” Forsskål held on until they reached a remote mountain village, where, the day after his burial, his corpse was dug up by treasure hunters. (They didn’t find any.) Baurenfeind and Berggren died at sea. Kramer expired in Bombay. Niebuhr took the overland route home, discarding his German identity and passing for half a year as a man named Abdullah.

The fate of Forsskål’s botanical specimens is a saga of its own. Some items were destroyed by customs officials expecting bribes. Chests of taxidermied animals and birds, mounted insects, and dried plants were damaged by pirates. Collections of fish rotted when the alcohol they were preserved in evaporated. Samples that made it to Copenhagen were neglected or discarded. Forsskål had discovered and catalogued hundreds of species, but according to Hansen, he is remembered in scientific annals only because his mentor, Carl Linnaeus, gave his name to a plant that grew from one of his seeds: Forsskaolea, a stinging nettle. (Colin Thubron, in his preface to this edition of Arabia Felix, is more sanguine on the subject of Forsskål’s legacy: “His herbarium is still in use.”) Niebuhr was offended by the four-word description Linnaeus appended to the Forsskaolea: “tenacissima, hispida, adhaereus, uncinata” (“stubborn, wild, obstinate, angular”) — but Hansen thinks it “hit upon the truth.”

The fate of Forsskål’s botanical specimens is a saga of its own. Some items were destroyed by customs officials expecting bribes. Chests of taxidermied animals and birds, mounted insects, and dried plants were damaged by pirates. Collections of fish rotted when the alcohol they were preserved in evaporated. Samples that made it to Copenhagen were neglected or discarded. Forsskål had discovered and catalogued hundreds of species, but according to Hansen, he is remembered in scientific annals only because his mentor, Carl Linnaeus, gave his name to a plant that grew from one of his seeds: Forsskaolea, a stinging nettle. (Colin Thubron, in his preface to this edition of Arabia Felix, is more sanguine on the subject of Forsskål’s legacy: “His herbarium is still in use.”) Niebuhr was offended by the four-word description Linnaeus appended to the Forsskaolea: “tenacissima, hispida, adhaereus, uncinata” (“stubborn, wild, obstinate, angular”) — but Hansen thinks it “hit upon the truth.”

Back in Denmark, Niebuhr paid for the publication of Forsskål’s manuscripts and Baurenfeind’s drawings, as well as his own diaries. He turned down an offer to captain an expedition to Norway, instead requesting a clerkship in the remote marshlands. The legend of his journey spread, but he persisted in a quiet life with his wife and children. He did not travel again.

Almost forty years ago, Kevin Pace, the narrator of Percival Everett’s tough and tender novel SO MUCH BLUE (Graywolf, $16), traveled to El Salvador with his best friend, Richard, on a mission to recover Richard’s brother, Tad, a.k.a. Fup — “the fuckup.” To find him, they relied on a deranged Vietnam vet known as the Bummer, who led them through the mountains to a village still stinking of ammonia from the soldiers’ .223s. Something terrible happened there, something Kevin still can’t talk — or even think — about. Then, in the back alley of a burning city, something worse happened.

Those aren’t the only secrets Kevin is keeping. So Much Blue is told in brief chapters that alternate between three times and places: El Salvador at the start of the civil war; Paris in the mid-Aughts, where Kevin had an affair with a watercolorist; and present-day New England. The big news from home is that Kevin’s teenage daughter is pregnant; fool that he is, he has promised not to tell his wife.

Kevin is a painter, something he talks about a lot, and he’s black, a fact you might miss if you read too quickly. Everett has written scathingly about race — in his novel Erasure, a black writer who can’t get published because he’s “not black enough” finds success with a novella originally called My Pafology — but Kevin’s race is less important to his identity than his art, or his loyalty to his friends. He’s successful, but he doesn’t care very much about the paintings he sells.

Some are good. Some not so. It’s really not up to me to judge and so I won’t. They are all whores, these paintings. . . . It’s not their fault and in fact I do not view that as a bad thing in and of itself. There really isn’t much wrong with being a whore, if it’s done well and without apology or qualification.

There is one painting that isn’t a whore. Kevin has been working on it for years in a barn out back. The novel begins with talk of its dimensions:

I had a mathematician friend tell me once, perhaps twice, that dimension is concerned with the constituent structure of all space and its relation to time. I did not understand this statement and still I do not, in spite of its undeniable, obvious poetic charm.

This painting’s particular measurements are twelve feet by twenty-one feet and three inches. “I cannot explain the three inches, but can say that they are crucial to the work.”

Collectors are rumored to have put bids on the painting, which annoys Kevin, but no one has ever been allowed in to see it: not his wife, not his kids, not Richard. The windows of the barn are sealed up. At one point Kevin buys a fly-killing contraption that sprays poison out of rotating tubes, thinking it would be a good way to booby-trap the building in case he dies suddenly and Richard can’t burn it down as he has promised to. (When he tests the chemical spray on another canvas, he is disappointed to discover that it makes the painting more interesting. “My plan for automated destruction had to be abandoned.”)

It doesn’t take much detective work to guess that the secret painting is a tortured monument to the irredeemable past, to what happened in El Salvador. Everett has a reputation as an experimentalist and a trickster, but if So Much Blue is subverting genres, that’s another one of its secrets. It’s as if Everett had set himself the task of writing a plain old novel with all the plain old novel-y stuff. The ingredients are the same as in Kehlmann: an artist-narrator, an extramarital affair, a haunted house. But Kehlmann gave me the heebie-jeebies, and Everett broke my heart.