Discussed in this essay:

Get Out, directed by Jordan Peele. Blumhouse Productions, QC Entertainment, and Monkeypaw Productions, 2017. 104 minutes.

Open Casket, by Dana Schutz. 2017 Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. March 17–June 11, 2017.

You are white—

yet a part of me, as I am a part of you.

That’s American.

Sometimes perhaps you don’t want to be a part of me.

Nor do I often want to be a part of you.

But we are, that’s true!

As I learn from you,

I guess you learn from me—

although you’re older—and white—

and somewhat more free.

—Langston Hughes

Early on, as the opening credits roll, a woodland scene. We’re upstate, viewing the forest from a passing car. Trees upon trees, lovely, dark and deep. There are no people to be seen in this wood—but you get the feeling that somebody’s in there somewhere. Now we switch to a different world. Still photographs, taken in the shadow of public housing: the basketball court, the abandoned lot, the street corner. Here black folk hang out on sun-warmed concrete, laughing, crying, living, surviving. The shots of the woods and those of the city both have their natural audience, people for whom such images are familiar and benign. There are those who think of Frostian woods as the pastoral, as America the Beautiful, and others who see summer in the city as, likewise, beautiful and American. One of the marvelous tricks of Jordan Peele’s debut feature, Get Out, is to reverse these constituencies, revealing two separate planets of American fear—separate but not equal. One side can claim a long, distinguished cinematic history: Why should I fear the black man in the city? The second, though not entirely unknown (Deliverance, The Wicker Man), is certainly more obscure: Why should I fear the white man in the woods?

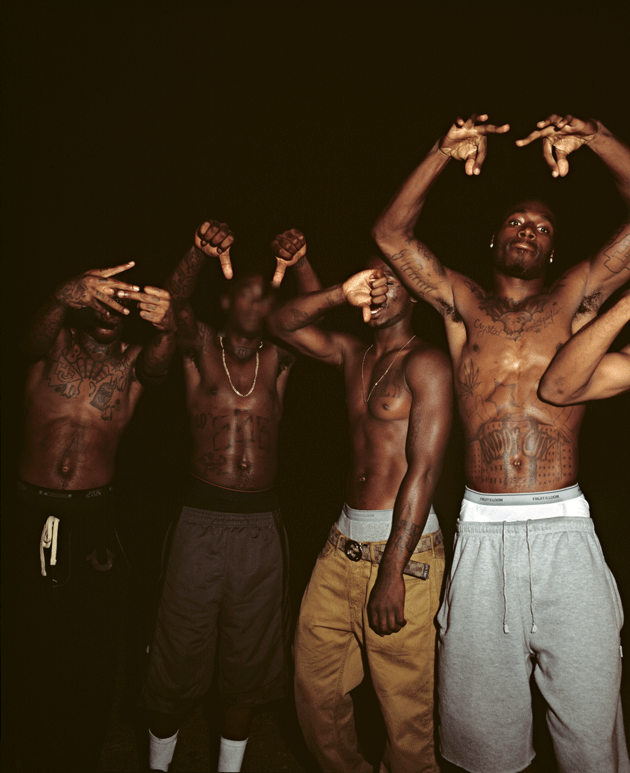

“Signs,” by Deana Lawson, from a series of staged photographs that explore the perception of race in American culture. Lawson’s work was on view last month as part of the Whitney Biennial at the Whitney Museum of American Art, in New York City. Courtesy the artist; Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago; and Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York City

A few years ago I interviewed Peele as he came to the end of a long run on the celebrated Comedy Central sketch show Key and Peele. On that occasion he spoke about comic reversals—“I think reversals end up being the real bread and butter of the show”—and about finding the emotional root of a joke in order to intensify it: “What’s the mythology that is funny just because people know it’s not true?” Get Out is structured around such inversions and reversals, although here “funny” has been replaced, more often than not, with “scary,” and a further question has been posed: Which mythology? Or, more precisely: Whose? Instead of the familiar, terrified white man, robbed at gunpoint by a black man on a city street, we meet a black man walking in the leafy white suburbs, stalked by a white man in a slow-moving vehicle from whose stereo issues perhaps the whitest song in the world: “Run, rabbit, run, rabbit, run run run …”

Get Out flips the script, offering a compendium of black fears about white folk. White women who date black men. Waspy families. Waspy family garden parties. Ukuleles. Crazy younger brothers. Crazy younger brothers who play ukuleles. Sexual psychopaths, hunting, guns, cannibalism, mind control, well-meaning conversations about Obama. The police. Well-meaning conversations about basketball. Spontaneous roughhousing, spontaneous touching of one’s biceps or hair. Lifestyle cults, actual cults. Houses with no other houses anywhere near them. Fondness for woods. The game bingo. Servile household staff, sexual enslavement, nostalgia for slavery—slavery itself. Every one of these reversals “lands”—just like a good joke—simultaneously describing and interpreting the situation at hand, and this, I think, is what accounts for the homogeneity of reactions to Get Out: It is a film that contains its own commentary.

For black viewers there is the pleasure of vindication. It’s not often they have both their real and their irrational fears so thoroughly indulged. For white liberals—whom the movie purports to have in its satirical sights—there is the cringe of recognition, that queer but illuminating feeling of being suddenly “othered.” (Oh, that’s how we look to them?) And, I suppose, the satisfaction of being in on the joke. For example, there is the moment when the white girl, Rose (Allison Williams), and her new black boyfriend, Chris (Daniel Kaluuya), hit a deer on the way to her parents’ country house. She’s driving, yet when the police stop them he’s the one asked for his license. Rose is sufficiently “woke” to step in front of her man and give the cop a self-righteous earful—but oblivious to the fact that only a white girl would dare assume she could do so with impunity. The audience—on both sides of the divide—groans with recognition. Chris himself—surely mindful of what happened to Sandra Bland, and Walter Scott, and Terence Crutcher, and Samuel DuBose—smiles wryly but remains polite and deferential throughout. He is a photographer, those were his photographs of black city life we saw behind the credits, and that white and black Americans view the same situations through very different lenses is something he already understands.

This point is made a second time, more fiercely, in one of the final scenes. Chris is standing in those dark woods again, covered in blood; on the ground before him lies Rose, far more badly wounded. A cop car is approaching. Chris eyes it with resigned dread. As it happens, he is the victim in this gruesome tableau, but neither he nor anyone else in the cinema expects that to count for a goddamned thing. (“You’re really in for it now, you poor motherfucker,” someone in the row behind me said. These days, a cop is apparently a more frightening prospect than a lobotomy-performing cult.) But then the car door opens and something unexpected happens: It is not the dreaded white cop after all but a concerned friend, Rod Williams (Lil Rel Howery), the charming and paranoid brother who warned Chris, at the very start, not to go stay with a load of white folks in the woods. Rod—who works for the TSA—surveys the bloody scene and does not immediately assume that Chris is the perp. A collective gasp of delight bursts over the audience, but in this final reversal the joke’s on us. How, in 2017, are we still in a world where presuming a black man innocent until proven guilty is the material of comic fantasy?

These are the type of self-contained, ironic, politically charged sketches at which Peele has long excelled. But there’s a deeper seam in Get Out, which is mined through visual symbol rather than situational comedy. I will not easily forget the lengthy close-ups of suffering black faces; suffering, but trapped behind masks, like so many cinematic analogues of the arguments of Frantz Fanon. Chris himself, and the white family’s maid, and the white family’s groundskeeper, and the young, lobotomized beau of an old white lady—all frozen in attitudes of trauma, shock, or bland servility, or wearing chillingly fixed grins. In each case, the eyes register an internal desperation. Get me out! The oppressed. The cannibalized. The living dead. When a single tear or a dribble of blood runs down these masks, we are to understand this as a sign that there is still somebody in there. Somebody human. Somebody who has the potential to be whole.

As the movie progresses we learn what’s going on: Black people aren’t being murdered or destroyed up here in the woods, they’re being used. A white grandmother’s brain is now in her black maid’s body. A blind old white gallerist hopes to place his brain in Chris’s cranium and thus see with the young black photographer’s eyes, be in his young black skin. Remnants of the black “host” remain after these operations—but not enough to make a person.

THE TIMES THAY AINT A CHANGING, FAST ENOUGH!, by Henry Taylor. The painting is based on the video made in the aftermath of the fatal shooting of Philando Castile by a Minnesota police officer in 2016. Taylor’s work was on view last month at the Whitney Biennial. Courtesy the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles

Peele has found a concrete metaphor for the ultimate unspoken fear: that to be oppressed is not so much to be hated as obscenely loved. Disgust and passion are intertwined. Our antipathies are simultaneously a record of our desires, our sublimated wishes, our deepest envies. The capacity to give birth or to make food from one’s body; perceived intellectual, physical, or sexual superiority; perceived intimacy with the natural world, animals, and plants; perceived self-sufficiency in a faith or in a community. There are few qualities in others that we cannot transform into a form of fear and loathing in ourselves. In the documentary I Am Not Your Negro (2016), James Baldwin gets to the heart of it:

What white people have to do is try to find out in their hearts why it was necessary for them to have a nigger in the first place. Because I am not a nigger. I’m a man…. If I’m not the nigger here, and if you invented him, you the white people invented him, then you have to find out why. And the future of the country depends on that.

But there is an important difference between the invented “nigger” of 1963 and the invented African American of 2017: The disgust has mostly fallen away. We were declared beautiful back in the Sixties, but it has only recently been discovered that we are so. In the liberal circles depicted in Get Out, everything that was once reviled—our eyes, our skin, our backsides, our noses, our arms, our legs, our breasts, and of course our hair—is now openly envied and celebrated and aestheticized and deployed in secondary images to sell stuff. As one character tells Chris, “black is in fashion now.”

To be clear, the life of the black citizen in America is no more envied or desired today than it was back in 1963. Her schools are still avoided and her housing still substandard and her neighborhood still feared and her personal and professional outcomes disproportionately linked to her zip code. But her physical self is no longer reviled. If she is a child and comes up for adoption, many a white family will be delighted to have her, and if she is in your social class and social circle, she is very welcome to come to the party; indeed, it’s not really a party unless she does come. No one will call her the n-word on national television, least of all a black intellectual. (The Baldwin quote is from a television interview.) For liberals the word is interdicted and unsayable.

But in place of the old disgust comes a new kind of cannibalism. The white people in Get Out want to get inside the black experience: They want to wear it like a skin and walk around in it. The modern word for this is “appropriation.” There is an argument that there are many things that are “ours” and must not be touched or even looked at sideways, including (but not limited to) our voices, our personal style, our hair, our cultural products, our history, and, perhaps more than anything else, our pain. A people from whom so much has been stolen are understandably protective of their possessions, especially the ineffable kind. In these debates my mind always turns to a line of Nabokov, a writer for whom arrival in America meant the loss of pretty much everything, including a language: “Why not leave their private sorrows to people? Is sorrow not, one asks, the only thing in the world people really possess?”

Two weeks after watching Get Out, I stood with my children in front of Open Casket, Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till, the black teenager who, in 1955, was beaten and lynched after being accused of flirting with a white woman. My children did not know what they were looking at and were too young for me to explain. Before I came, I had read the widely circulated letter to the curators of the Whitney Biennial objecting to their inclusion of this painting:

I am writing to ask you to remove Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket and with the urgent recommendation that the painting be destroyed and not entered into any market or museum … because it is not acceptable for a white person to transmute Black suffering into profit and fun, though the practice has been normalized for a long time.

I knew, from reading about this debate, that in fact the painting had never been for sale, so I focused instead on the other prong of the argument—an artist’s right to a particular subject. “The subject matter is not Schutz’s; white free speech and white creative freedom have been founded on the constraint of others, and are not natural rights.”

I want to follow the letter very precisely, along its own logic, in which natural rights are replaced with racial ones. I will apply it personally. If I were an artist, and if I could paint—could the subject matter be mine? I am biracial. I have Afro-hair, my skin is brown, I am identified, by others and by myself, as a black woman. And so, by the logic of the letter—if I understand it correctly—this question of subject matter, in my case, would not come up, as it would not come up for the author of the letter, Hannah Black, who also happens to be biracial, and brown. Neither of us is American, but the author appears to speak confidently in defense of the African-American experience, so I, like her, will assume a transnational unity. I will assume that Emmett Till, if I could paint, could be my subject too.

Now I want to inch a step further. I turn from the painting to my children. Their beloved father is white, I am biracial, so, by the old racial classifications of America, they are “quadroons.” Could they take black suffering as a subject of their art, should they ever make any? Their grandmother is as black as the ace of spades, as the British used to say; their mother is what the French still call café au lait. They themselves are sort of yellowy. When exactly does black suffering cease to be their concern? Their grandmother—raised on a postcolonial island, in extreme poverty, descended from slaves—knew black suffering intimately. But her grandchildren look white. Are they? If they are, shouldn’t white people like my children concern themselves with the suffering of Emmett Till? Is making art a form of concern? Does it matter which form the concern takes? Could they be painters of occasional black subjects? (Dana Schutz paints many subjects.) Or must their concern take a different form: civil rights law, public-school teaching? If they ignore the warnings of the letter and take black suffering as their subject in a work of art, what should be the consequence? If their painting turns out to be a not especially distinguished expression of or engagement with their supposed concern, must it be removed from wherever it hangs? Destroyed? To what purpose?

Often I look at my children and remember that quadroons—green-eyed, yellow-haired people like my children—must have been standing on those auction blocks with their café au lait mothers and dark-skinned grandmothers. And I think too of how they would have had many opportunities to “pass,” to sneak out and be lost in the white majority, not visibly connected to black suffering and so able to walk through town, marry white, lighten up the race again. To be biracial in America at that time was almost always to be the issue of rape. It was in a literal sense to live with the enemy within, to have your physical being exist as an embodiment of the oppression of your people. Perhaps this trace of shame and inner conflict has never entirely left the biracial experience.

To be biracial at any time is complex. Speaking for myself, I know that racially charged historical moments, like this one, can increase the ever-present torsion within my experience until it feels like something’s got to give. You start to yearn for absolute clarity: personal, genetic, political. I stood in front of the painting and thought how cathartic it would be if this picture filled me with rage. But it never got that deep into me, as either representation or appropriation. I think of it as a questionably successful example of both, but the letter condemning it will not contend with its relative success or failure, the letter lives in a binary world in which the painting is either facilely celebrated as proof of the autonomy of art or condemned to the philistine art bonfire. The first option, as the letter rightly argues, is often just hoary old white privilege dressed up as aesthetic theory, but the second is—let’s face it—the province of Nazis and censorious evangelicals. Art is a traffic in symbols and images, it has never been politically or historically neutral, and I do not find discussions on appropriation and representation to be in any way trivial. Each individual example has to be thought through, and we have every right to include such considerations in our evaluations of art (and also to point out the often dubious neutrality of supposedly pure aesthetic criteria). But when arguments of appropriation are linked to a racial essentialism no more sophisticated than antebellum miscegenation laws, well, then we head quickly into absurdity. Is Hannah Black black enough to write this letter? Are my children too white to engage with black suffering? How black is black enough? Does an “octoroon” still count?

When I looked at Open Casket, the truth is I didn’t feel very much. I tried to transfer to the painting—or even to Dana Schutz—some of the cold fury that is sparked by looking at the historical photograph of Emmett Till, whose mother insisted he have an open casket, or by considering the crimes of Carolyn Bryant, the white woman who falsely accused him of harassing her, but nothing I saw in that canvas could provoke such an emotion. The painting is an abstraction without much intensity, and there’s a clear caution in the brushstrokes around the eyes: Schutz has gone in only so far. Yet the anxious aporia in the upper face is countered by the area around the mouth, where the canvas roils, coming toward us three-dimensionally, like a swelling—the flesh garroted, twisted, striped—as if something is pushing from behind the death mask, trying to get out. That did move me.

What’s harder to see is why this picture was singled out. A few floors up hung a painting by a white artist, Eric Fischl, A Visit to?/?A Visit from?/?The Island, in which rich white holidaymakers on a beach are juxtaposed with black boat people washed up on the sand, some dead, some half-naked, desperate, writhing, suffering. Painted in 1983, by an artist now in his late sixties, it is presumably for sale, yet it goes unmentioned in a letter whose main effect has been to divert attention from everything else in the show. Henry Taylor, Deana Lawson, Lyle Ashton Harris, and Cauleen Smith were just a few of the artists of color lighting up the Whitney in a thrilling biennial that delved deep into black experience, illuminating its joys and suffering both. Looking at their work, I found I resented the implication that black pain is so raw and unprocessed—and black art practice so vulnerable and invisible—that a single painting by a white woman can radically influence it one way or another. Nor did I need to convince myself of my own authenticity by drawing a line between somebody else’s supposed fraudulence and the fears I have concerning my own (thus evincing an unfortunate tendency toward overcompensation that, it must be admitted, is not unknown among us biracial folks). No. The viewer is not a fraud. Neither is the painter. The truth is that this painting and I are simply not in profound communication.

This is always a risk in art. The solution remains as it has always been: Get out (of the gallery) or go deeper in (to the argument). Write a screed against it. Critique the hell out of it. Tear it to shreds in your review or paint another painting in response. But remove it? Destroy it? Instead I turned from the painting, not offended, not especially shocked or moved, not even terribly engaged by it, and walked with the children to the next room.

We have been warned not to get under one another’s skin, to keep our distance. But Jordan Peele’s horror-fantasy—in which we are inside one another’s skin and intimately involved in one another’s suffering—is neither a horror nor a fantasy. It is a fact of our experience. The real fantasy is that we can get out of one another’s way, make a clean cut between black and white, a final cathartic separation between us and them. For the many of us in loving, mixed families, this is the true impossibility. There are people online who seem astounded that Get Out was written and directed by a man with a white wife and a white mother, a man who may soon have—depending on how the unpredictable phenotype lottery goes—a white-appearing child. But this is the history of race in America. Families can become black, then white, then black again within a few generations. And even when Americans are not genetically mixed, they live in a mixed society at the national level if no other. There is no getting out of our intertwined history.

But in this moment of resurgent black consciousness, God knows it feels good—therapeutic!—to mark a clear separation from white America, the better to speak in a collective voice. We will not be moved. We can’t breathe. We will not be executed for traffic violations or for the wearing of hoodies. We will no longer tolerate substandard schools, housing, health care. Get Out—as evidenced by its huge box office—is the right movie for this moment. It is the opposite of post-black or postracial. It reveals race as the fundamental American lens through which everything is seen. That part, to my mind, is right on the money. But the “us” and “them”? That’s a cheaper gag. Whether they like it or not, Americans are one people. (And the binary of black and white is only one part of this nation’s infinitely variegated racial composition.) Lobotomies are the cleanest cut; real life is messier. I can’t wait for Peele—with his abundant gifts, black-nerd smarts, comprehensive cinematic fandom, and complex personal experience—to go deeper in, and out the other side.