In his heart, Simon Yakida knew he was digging his own grave.

A few days earlier, clashes between government troops and rebel forces near Bamurye, Yakida’s village in South Sudan, had left three soldiers dead. Now the local military commander stood before him, gesturing at one of the bodies. He told Yakida, “Killing you is payback for this soldier.”

Bamurye, a farming community whose residents live in mud-and-thatch huts called tukuls, lies in the southern part of the country. To feed his two wives and nine children, Yakida, a thirty-two-year-old with close-cropped hair and a wiry frame, grew cassava, maize, and sorghum. The work had always been hard, but his life was peaceful. In recent months, however, the soldiers in the local barracks had grown increasingly abusive—detaining and mistreating civilians and accusing them of supporting the antigovernment rebels. In February, the killings began: Three young men were murdered by soldiers in retaliation for recent battlefield losses. Most in the village, including Yakida’s family, had already fled to Uganda; Yakida was on his way when the troops arrested him.

A child carrying water-filled jerricans at the Laufori refugee collection point, on the border of Uganda and South Sudan. All photographs by Natalia Jidovanu

The soldiers watched as Yakida carved out a knee-deep hole. The commander ordered him to roll the corpse into the pit and cover it with soil. Famished, thirsty, and exhausted, Yakida complied. Once the work was done, the soldiers tied him to a wooden pole, the remnants of a rudimentary hut.

“Where is the headman of the village?” the commander barked. “Where is Abu Sala?”

Abu Sala is what people in Bamurye called Alex Kajoba, a night watchman at the local medical dispensary who was known for advocating on behalf of villagers who had been detained at the barracks. It wasn’t a question but a threat; both men knew exactly where Abu Sala was and why he wouldn’t be coming to Yakida’s aid.

Eventually, the soldiers—members of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (S.P.L.A.)—untied Yakida and ordered him to sit on top of the fresh grave. They bound his hands and ankles. One of the soldiers offered a salute, then cocked his weapon. The commander ordered him to fire, and he pulled the trigger.

Yet two days later, Yakida stood before me, wearing a gray polo shirt with marks & spencer emblazoned on it and ill-fitting jeans that read bing boss. We were in Laufori, a Ugandan border town with dusty dirt roads and wooden stalls where you could buy cheap flip-flops and warm Cokes. Yakida was living beneath an immense mango tree, still separated from his family. His lean arms bore the marks from where the rope had dug into them.

Tears spilled down his drawn cheeks as he told me about his failed execution. A bullet passed through his oversize shirt, just beneath his left armpit. On the second and third attempts, the rifle jammed. After an argument among the troops, a soldier allowed him to leave, and Yakida joined the tide of refugees pouring out of Bamurye and dozens of other South Sudanese villages. He seemed broken by the ordeal.

After Yakida told me his story, I asked if he had any questions for me. “These are government soldiers. They’re supposed to be protecting civilians, but they’re the ones who are killing us,” he replied. “Why are they killing the people they’re supposed to be protecting?”

One afternoon this February, I stood on the side of a dirt track that led from South Sudan to Uganda. It was the worst time to travel, with the midday sun baking the road, but at least one refugee crossed the border every minute, coated in a mix of sweat and dust from the rust-colored earth. For a week, I staked out trails like this, in an attempt to understand what has become the fastest-growing refugee crisis on the planet: a wave of ethnic cleansing that experts warn may tip into genocide.

There were three other roads nearby with refugees making the same trek. Many had run with only the clothes they were wearing—threadbare dresses and long colorful skirts, blouses held together by safety pins, a soiled ted nugent: body count T-shirt, a pair of dress pants several sizes too big belted around a diminishing waist with twine, an aqua-blue sandal on one foot and a battered brown loafer on the other.

The current conflict has deep roots. From 1983 to 2005, southern Sudanese fought a civil war against Sudan’s government. In 2011, the South gained its independence, becoming the world’s newest nation. Salva Kiir, a member of the largest of the country’s sixty-four ethnic groups, the Dinka, became the first president of the Texas-size nation of 12 million.

South Sudan was an American nation-building experiment, the recipient of $11 billion in assistance since 2005—perhaps the largest investment the United States has made in sub-Saharan Africa. Washington and other international partners trained soldiers and mentored government officials, but they ignored the country’s stunted economic, military, and political development, which left South Sudan mired in corruption, ethnoracism, and violence. Six years after independence, most people still lack electricity, phone networks are spotty, and paved roads are nonexistent outside the capital, Juba.

In July 2013, South Sudan began to unravel. Riek Machar, the vice president—a member of the second-largest tribe, the Nuer—was fired by Kiir, then announced that he would challenge him in upcoming elections, which were never held. That December, government forces killed large numbers of Nuer soldiers and civilians on the streets of Juba. Rebel forces loyal to Machar responded, massacring Dinkas in villages and towns in the north.

In 2014, as the conflict raged between the S.P.L.A. and Machar’s rebels, known as the Sudan People’s Liberation Army—In Opposition (I.O.), Kiir visited the White House. A former guerrilla, he is often photographed in one of the cowboy hats given to him by President George W. Bush or Secretary of State John Kerry. Unwilling to pressure Kiir and the leaders they had fostered, the Obama Administration failed to impose a unilateral arms embargo. An eleventh-hour push for an international arms ban at the U.N. Security Council collapsed, in part because the outgoing administration lacked sufficient political capital. As a result, Kiir has been able to purchase $1 billion worth of arms, including tanks and helicopter gunships.

During the early stages of the current conflict, the south of the country had been largely spared. But South Sudan is riven by all manner of differences and enmities. In the north, the Dinka are cattle keepers. The south is made up of the Equatorias—Central, Western, and Eastern. The region is the breadbasket of the country, with fields of cassava, sorghum, peanuts, and maize and orchards of fruit trees. For years, Dinkas had moved huge herds into Equatorian farmland, and in 2015, these land grabs escalated into skirmishes between the S.P.L.A. and homegrown militias.

Many of the militia fighters allied themselves with the I.O., and ever since, they have clashed with the S.P.L.A. The government has responded by killing civilians throughout the Equatorias.

These attacks set in motion the exodus unfolding before me. Women toted impossibly large bundles atop their heads, their necks kept ramrod stiff, their bodies subtly shifting to keep the parcels stationary. Many had tiny babies tightly swaddled and strapped to their backs.

The men and boys, their noses polka-dotted with perspiration, pushed bicycles—some with only one semi-inflated tire—overloaded with heavy sacks of maize flour, sorghum, or beans; bottles glowing with golden cooking oil, a washbasin, a few plastic bowls; 1970s-vintage hard plastic suitcases with broken locks replaced by rope; foam mattresses rolled around shovel heads, bicycle parts, or coils of wire; yellow jerricans for hauling water and blue plastic jugs that once held motor oil; a homemade wooden cage barely larger than the chickens crammed inside it.

Until last July, about 231,000 South Sudanese had fled to Uganda. The number has risen to 834,000 and shows no signs of slowing. Kiir’s government has said that his soldiers are fighting a counterinsurgency against the I.O.; the official line is that civilian deaths are either regrettable collateral damage or the isolated acts of rogue soldiers.

What I discovered is far different: a coordinated campaign of atrocity and terror by Kiir’s forces that refutes the government’s narrative. For more than a month I traveled by foot, motorcycle, car, truck, motorboat, ferry, and prop plane through South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Uganda, visiting backland border crossings, refugee collection points, and formal and informal settlements.

I spoke with more than 250 refugees and internally displaced people—from villages spanning some 300 miles, from Arapi in the east to Yambio in the west. Multiple eyewitnesses described attacks by S.P.L.A. soldiers on twenty-six communities, resulting in no fewer than 141 deaths and possibly close to 400. Individual witnesses from nine other villages told me of another twenty-eight killings. Survivors also offered harrowing accounts of rape, torture, assault, mutilation, looting, the destruction of homes, and other crimes of war. These attacks, in addition to news reports of atrocities elsewhere in the Equatorias, reveal a systematic effort carried out by government forces to empty the southern part of South Sudan.

Since the U.S. election, attacks on civilians have dramatically increased, leading some analysts to suggest that the Kiir regime is emboldened by what it sees as the Trump Administration’s hands-off policy. In fact, Kiir said in a speech this February, it was “no secret we had a strong feeling that the previous U.S. administration might have sought a regime change agenda…. We know that the new U.S. administration will take a different direction on South Sudan.”

The price of America’s neglect is now being borne by South Sudanese in villages like Bamurye. The Equatorias, I found, are the site of an ethnic-cleansing campaign that threatens to extinguish the entire region. But as the international community wrings its hands and the Trump Administration warns that “the parties must cease hostilities [and] engage in meaningful and inclusive dialogue,” more than 15,000 refugees cross the southern border each week. Given the scale of the government’s atrocities, how much time is left before a stillborn state is transformed into a ghost nation?

Northern Uganda is dotted with new or expanding refugee collection points and settlements run by the Ugandan government and the United Nations. But often the places where I found refugees weren’t even official checkpoints.

One such crossing is the Kayo stream. During the rainy season, you can pay strong young men to half-swim, half-carry you through the swollen torrent of rushing water. In February, it was a parched creek bed. Clamber down a steep rock formation in South Sudan, and when you reach the sandy embankment on the other side, you’ve entered Uganda.

A hundred feet from the border, I met fifty-two-year-old Peter James. His red baseball cap shielded his eyes from the sun as we talked about his hometown, a village called Litoba, several miles north. James, one of the five people from Litoba I spoke with, told me that Dinka soldiers are coming down to the Equatorias, where they are “robbing people, they are killing, they are even raping our wives and children.” James believed that as many as twenty civilians had been killed in his village.

Two women leaving the Pagrinya refugee settlement, in Uganda, to return to their homes after receiving rations from the World Food Program

Joshua Mari couldn’t run when troops began terrorizing civilians in Litoba. His family fled and left behind the seventy-five-year-old, who is exceptionally tall and stooped, and suffers from back problems. Days later, a motorcycle driver rescued him from the battered village. “The government has been killing people,” he told me in a shaky baritone that rumbled out of his rib cage. “I had to leave because even though I’m sick, they would kill me.”

It was a forty-five-minute walk from the Kayo stream to the Afoji refugee collection point in Uganda, a humble marketplace transformed into a medical-screening and registration center where women cradled squalling infants and men sat despondent amid piles of battered luggage.

Veronica Keji spent one week “footing” through the bush to get to Afoji from Mondikolok, another village in the deep south of South Sudan. In January, Keji, who is sixty-one, was returning from a nearby borehole with her water can when gunshots rang out. She saw soldiers—S.P.L.A. in uniform—so she dashed into the tall grasses surrounding the village. She crouched, listening to the rattle of gunfire as smoke began to sting her eyes.

In the scalding heat of Afoji, Keji balled her right hand into a fist and pounded her open left hand—slap, slap, slap, slap—mimicking the sound of gunshots. The soldiers, she explained, set fire to nearby crops and the sun-scorched grass, forcing her deeper into the bush. After the S.P.L.A. left Mondikolok, Keji returned to find torched homes and the scattered bodies of her neighbors. Eight lay dead, including a woman who had been thrown into a burning tukul and a bedridden man executed at close range. Soon after, she left for Afoji. “We heard there might be others, but this is what we saw,” Keji explained.

I searched for other refugees from Mondikolok to confirm or contest Keji’s recollections.* Another woman at Afoji offered a nearly identical account of the attack, including the disabled man who was killed. That murder, of someone completely defenseless, stayed with me. Over the next few days, I learned about eight people killed in the village of Lire, another seven slain in Pagelle, two people gunned down in Kit, five killed in Mundari, ten massacred in Lejo, one attack in Limi that claimed between three and fifteen lives, and a second that killed between four and eleven, but I kept thinking about the man in Mondikolok.

Fifteen miles to the east, at the Laufori refugee collection point, kids with bruised feet trailed their parents from one snaking line to another. Nearby, I spoke with Emmanuel Diliga, a forty-seven-year-old Episcopal priest clad in tattered dress pants, a green shirt, and a striped sweater-vest. Diliga looked dignified but exhausted. He had spent several hours trekking through the bush in ninety-five-degree heat with nothing to eat or drink. “On January twenty-second, the S.P.L.A. went to look for the I.O. in Mondikolok. They said civilians were killed in a crossfire, but that is not true,” he told me with the cadence of an experienced public speaker. “A woman was raped, and her body burned when they set fire to the grass. An older man who is disabled was pulled out of his bed and shot. Six people were killed.”

Refugees load their belongings onto a motorcycle at the Afoji collection point, at the Ugandan border

Two days later, I met Helen Poni, a slight twenty-two-year-old whose eyes were heavy with concern. She was from Bamurye but had family in Mondikolok. One of them was Meje, her father-in-law. “A relative tried to safeguard him, but he can’t move. Meje said, ‘Leave me. You better run or you’re going to die,’” she told me. So he was left in his bed. Her brother-in-law went back later, found Meje’s corpse, and buried him.

Finally I had a name for the disabled man. I heard it again, several days later, when I traveled to the Palorinya refugee settlement, a palm-tree-studded wilderness where the sun was blistering, water was scarce, and gaunt children dug into the ground, hunting for rodents to supplement their families’ diets. There, I met forty-one-year-old Pilister Kaku, who told me that Samuel Mori Meje was her brother. “They said he was an I.O., but he can’t even walk,” she told me plaintively. In total, she said, six people were killed.

A few of the Mondikolok refugees I spoke with mentioned that, hours before the killings, a group of rebels had ambushed government forces nearby. But the I.O. soon withdrew. The S.P.L.A. then attacked local civilians in retaliation. “The rebels weren’t even doing anything then,” Veronica Keji said. “They weren’t around.”

Many in the region express support for the I.O. Some men have joined them; others supply them with food, although not always by choice. In Western Equatoria, they call them “the boys” or “our boys,” despite looting, child abductions, rape, and the murder of civilians at their hands. (According to locals, the I.O. are responsible for far fewer atrocities than the S.P.L.A.) Attacks by “the boys” against government forces have led to heavy-handed reprisals on minority communities across the Equatorias. The current campaign ramped up following rebel ambushes and targeted killings, late last year, of Dinka civilians on the roads between Juba and Yei (twenty-one dead), Nimule (one), and Kajo-Keji (eleven), in addition to ongoing attacks on S.P.L.A. forces. There’s a simple pattern: The I.O. attacks, and the government retaliates against civilians.

What happened in Mondikolok has happened in numerous villages. Details of government reprisals varied, but residents of thirty-five communities in Eastern, Central, or Western Equatoria described a consistent pattern. Survivors identified the offending troops as almost exclusively Dinkas, whom they recognized by their language, build, and distinctive tribal scars. Those soldiers, they said, entered villages on foot or in military pickup trucks, saying little or nothing before opening fire with assault rifles. The troops didn’t need to wipe out an entire community to cleanse it. Killing four or eight or ten civilians—and often setting fire to a handful of homes—was enough to send survivors scrambling for the border.

One high-ranking S.P.L.A. officer from the Equatorias, Thomas Cirillo Swaka, confirmed these accounts in a resignation letter addressed to President Kiir:

S.P.L.A. soldiers from the Dinka ethnic group have been strategically deployed and posted in non-Dinka areas to support the policy of land occupation and enforcing the agenda of forceful Dinkanization and domination of the country.

Scores of fellow Equatorians, victims of what Cirillo called “ethnic cleansing, forceful displacement of people from their ancestral lands, and ethnic domination,” say this is a land grab, that they’ve lost their homes for the sake of the massive cattle herds of the S.P.L.A. senior command and the Dinka elite.

President Kiir’s press secretary, Ateny Wek Ateny, told me that such refugees have a “hidden agenda” and a grudge against fellow South Sudanese. I told him that refugees from the Kuku, Madi, Acholi, Kakwa, and other minority peoples all recounted to me stories of abuse by Dinka soldiers. “Whatever community you’re talking to, they will tell you rubbish about other communities,” he said. “When you are in a refugee camp, you have to justify the reason you left your country. So you have to create a story to allow you to stay in another country.”

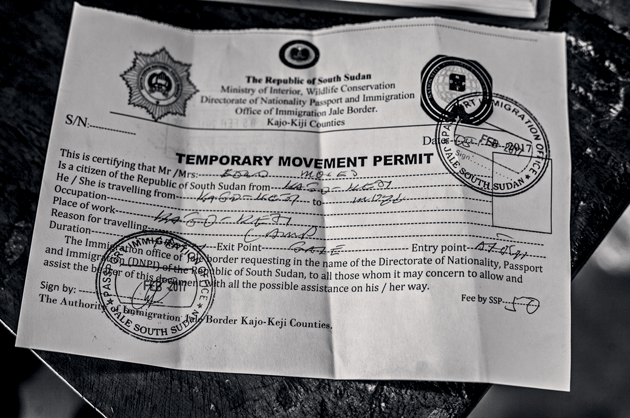

A refugee’s receipt of payment at Afoji. South Sudanese officials charge 50 South Sudanese pounds to cross into Uganda

An S.P.L.A. spokesman similarly dismissed suggestions of ethnic cleansing by government forces, alleging that representatives of the affected communities in South Sudan’s parliament would have held the government accountable. But politicians are hamstrung or in Kiir’s pocket. A parliamentarian from a minority ethnic group told me that he didn’t believe ethnic cleansing was occurring, even as he admitted that the S.P.L.A. was a private militia of Kiir’s party. “I take it as the behavior of untrained, unprofessional soldiers, based on tribal thinking,” he said of the rampant violence. He seemed to want to say more, but such is the state of affairs in South Sudan. Careless honesty can mean detention, disappearance, or death.

International observers can be far more frank. In late 2016, the U.N. Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan conducted two fact-finding missions across the country and in refugee camps in neighboring nations. “We found ethnic cleansing is under way,” Yasmin Sooka, the chairperson, told me—noting that civilians perceived as supporting the opposition were being attacked by Kiir’s government as if they were combatants. “What is happening is definitely ethnically targeted.”

From the refugee camps, I made my way west to a town called Salia Musala. The road threaded Ugandan villages on one side and Congolese villages on the other. I found myself at the edge of a dusty marketplace of shuttered wooden shacks. A three-trunked tree stood just beyond; locals told me that it marked the place where the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, and South Sudan meet. A group of Congolese soldiers sat silhouetted against thick green bushland that climbed the nearby hills.

There, I spoke with David Komakech, an intelligence officer with the Uganda People’s Defence Force, who told me that 230 refugees had passed through the area the day before. I asked him what he’d heard from inside South Sudan. “When women go to collect food from the garden, they are raped. And if you’re a man, you will be killed,” Komakech said. “They’ve burned all the villages—hundreds—all along the border.”

Just inside Congo, I found a group of about twenty-five ethnic Kakwas who had fled their homes outside Yei—a strategic town that serves as a regional hub for transport and trade with South Sudan’s neighbors. Forty-two-year-old Jacob Michael Karaba, an Episcopal archdeacon from the Diocese of Yei, was one of several adults who had traveled with a large group of teenagers from the village of Lasu. He told me that it had taken him three days to get to the border.

Karaba explained that since last July, more than 100 people from his area had been killed by S.P.L.A. soldiers. “If you run, they’ll kill you. If you don’t run, then they’ll kill you. If youths are caught like this,” he said, gesturing to the group of children and teens—all elbows and knees—sitting silently in the shade of a tree to my right, “soldiers will say they’re a group of I.O. and kill them.” At that, the kids, led by two teenaged girls, chimed in to confirm the account.

Karaba, dressed in a gray sweater-vest and clerical collar, told me that for more than twenty miles, between Yei and this border zone, most of the homes had been burned by the S.P.L.A. “There is nobody in the bomas, the payams. Nobody,” he explained, referring to the administrative units that fall between villages and counties. “People are just scattered in the bush.” A United Nations map created from satellite photos of Yei and the surrounding area, taken in March, shows 18,318 destroyed structures across 1,405 square miles, including the area where Karaba traveled. U.N. analysts say most of the homes appear to have been burned.

In March, I boarded a prop plane in Juba that deposited me on a dirt airstrip in Yambio, near the Congolese border in Western Equatoria. The area is home to the Azande ethnic group, communities of farmers that have suffered at the hands of government troops. At the encampments in town, people were living out in the open with little in the way of food. There, I met Ismail Nelson. On New Year’s Day, he was on his way to the local Episcopal church to celebrate Sunday mass when Dinka soldiers entered Bazumburu, a village outside Yambio. They grabbed him, bound his hands, and forced him to the ground.

A soldier stomped on the back of Nelson’s neck, driving his face into the dirt. Within moments, a machete slashed through Nelson’s skin and into the back of his skull. Then another blow to the back of his head. The soldier turned him over, sliced through his left cheek, then cut open his throat. Another soldier hacked away at a second man, several feet away. The two victims, dazed and bleeding, were dragged into an empty tukul, which the S.P.L.A. troops set on fire.

“Get up,” Nelson heard a voice booming in his head. “Get up!” He later thought it might be a spirit. Whatever it was, it pushed Nelson to rouse himself and help the other man out of the flames.

Nelson lurched toward the shade of a tree and dropped to the ground, trying to regain his senses. Then he forced himself to his feet and staggered to the main road. He was so mutilated that people didn’t recognize him, but someone finally called his name and asked, “Is that you?” A fellow villager managed to get word to one of Nelson’s sons, who took his father to the hospital in Yambio.

Outside Laufori, a man travels back into South Sudan to attempt to recover belongings from his home in Bamurye. It can take families several trips to transport their belongings across the border, risking attack by the S.P.L.A.

Even though we spoke through an interpreter, I noticed that Nelson was stammering and repeating himself. “I used to speak fluently,” he said. His wife told me his psychological trauma was even more profound than his physical scars. “I thought I would definitely be killed. I thought only about God,” Nelson told me with his bone-in-the-throat stutter.

Early one morning, a local guide and I left Yambio, to find Nelson’s village and others that had endured violence. We bounced down the rough dirt track in a Toyota Land Cruiser, following the path of least potholes. The sky brightened, the immense orange sun climbing higher over the verdant fields and emerald-topped trees. Forty minutes and fifteen miles later, we reached the burned homes of Bazungua. There was a cluster of flame-scorched tukuls here, and another a short distance away—incomplete squares of tan mud bricks, homes now charred, blackened, and roofless.

We drove on to Bodo, with burned out, roofless tukuls flanking the road. Not far away, house after house sat untouched by flame but eerily empty, as if hit by an epidemic. A small market along the main drag was deserted. The Peace Restaurant and Bar was shuttered. We pressed onward, passing fields and garden plots—filled with cassava, peanuts, and maize—all abandoned. I thought of the families who fled to Yambio and told me they feared starvation.

The devastation had reached Gitikiri, six miles to the east. More burned, abandoned tukuls. It was silent but for birdsong. Even the dogs had disappeared.

We jolted along, past palms and towering, fruit-laden mango trees, then a blackened stretch of ground, a field put to flame. There were even more burned tukuls in Bazumburu, on both sides of the road. “S.P.L.A.,” my guide said, acknowledging the handiwork of the soldiers, as he nodded toward another cluster of charred homes.

A few minutes later, we climbed out of the Land Cruiser and followed a ribbon-thin path that opened to a patch of scorched earth barely visible from the road. Off to the right, there was a rectangular tukul, missing its roof, ashes inside. A few paces away were the remains of another structure—just a semicircle of six charred branches sticking out of the ground. “This one was the kitchen,” my guide said, gesturing to the long, grooved grinding stone, now blackened by flame. Nearby, I found what looked to be a fresh grave.

Leaving Nelson’s village, we headed back down the road into ravaged areas of Gitikiri, Bodo, and Bazungua, finding one hut and one home after another, burned. Broken dishes were scattered among the ashes, torn clothes, a charred bicycle, an orphaned metal plate. I stared at painted white runes, still visible on one scorched tukul. They told a story: Three children had lived here, and had been vaccinated for polio last year. Now there were only charred wooden beams that once supported the roof. The kids were gone.

After South Sudan erupted in civil war in 2013, tens of thousands of civilians ran to United Nations bases, seeking protection from rampaging soldiers. Many have been stranded there ever since. Today, more than 200,000 South Sudanese live behind berms and razor wire in these sanctuaries-cum-prisons, 3.6 million have fled their homes, and more than 7.5 million need aid and protection. With farmers separated from their fields and relief agencies unable to reach large parts of the country, the resulting famine has left 100,000 South Sudanese in imminent mortal danger. One million more are at risk of starvation in the near future—one of four hunger crises across the Middle East and Africa that together, according to the U.N., constitute the greatest humanitarian disaster since World War II.

Last November, the United Nations also began warning about the potential for genocide in South Sudan. Yasmin Sooka uttered the name synonymous with African holocausts: Rwanda—where, in 1994, 800,000 people were killed in one hundred days, about 333 murders an hour, more than five lives exterminated every minute.

When I met with South Sudanese activists, politicians, and religious leaders, they often skirted the topic of genocide. In a nation where local civil society advocates and journalists have been harassed, tortured, and even killed for dissenting views, it’s too dangerous for most to talk openly about genocide or accuse the government of ethnic cleansing even as similar campaigns rage farther north, in the states of Jonglei, Upper Nile, and Western Bahr el Gazal.

In a low-slung beige building inside a compound on one of Juba’s anonymous unpaved streets, I met Edmund Yakani, a lawyer who once investigated atrocities in Darfur for the U.N. Today, he is the most outspoken human rights activist in South Sudan, a man who says aloud what others will only whisper in private. “Genocide is in the making. Crimes against humanity are in the making,” he told me as we sat in his conference room in February. “If we don’t defuse it right now, the violence could escalate to something worse than Rwanda.”

Yakani argued that America has a special obligation to his nation because South Sudan is a product of U.S. foreign policy. “We need the leaders of the United States to take responsibility to ensure that South Sudan is a stable, peaceful, and united country,” he said.

A day earlier, a bipartisan coalition of American legislators had sent a letter to President Trump, raising the specter of genocide and imploring him to appoint a special envoy to “bring urgently needed diplomatic leadership to international efforts to achieve a sustainable peace” in South Sudan. “Your swift action on this matter will make a difference in millions of lives,” they wrote.

One of the legislators who signed the letter was Michael Capuano, a Democratic representative from Massachusetts and a co-chair of the Congressional Caucus on Sudan and South Sudan. “Not being able to do something is not the same as not being able to push for it,” he told me. He believes that the United States has a duty to stop “the murder of tens of thousands, if not more, innocent, unarmed civilians,” he said. “I don’t think this is at the top of the administration’s agenda, but it better be close to it, because if it isn’t they could end up with a real tragedy on their hands. And it will be on them if it happens.”

Speaking at the Council on Foreign Relations in March, Nikki Haley, the administration’s ambassador to the United Nations, described the situation in South Sudan as a “civil war” with “no political solution in sight.” She threatened that “if the government is not taking care of their own people, we need to have strong actions that condemn them.” She said the United States intends to “challenge member states to start walking the walk and not just talking the talk of human rights.”

But there’s little indication that the administration is moving toward a coherent plan, let alone appointing a special envoy. “A policy review is under way with regard to South Sudan, and I’m not going to get ahead of that process or speculate on its outcomes,” a White House official who spoke on the condition of anonymity told me. “We continue to press directly the government of South Sudan to do more to end attacks on its own civilians and create the conditions for peace.”

Neither Haley’s office nor the White House would concede that Kiir’s campaign of murder and massacre amounted to ethnic cleansing, though the ambassador did eventually call South Sudan’s famine “man-made” and refer to “an apparent campaign against the civilian population.” I asked a State Department spokesman the same question. Instead of answering, he expressed concern about “reports that some civilians are being targeted on an ethnic basis” without attributing the attacks to any particular party.

Kate Knopf, a South Sudan expert who heads the Pentagon’s Africa Center for Strategic Studies, told me that substantial U.S. diplomatic engagement and economic assistance are essential to any path forward for South Sudan. But after pouring in billions of dollars, supporting Salva Kiir’s regime, training the S.P.L.A., and holding back on an arms embargo that helped Kiir to go on a weapons-buying spree, the U.S. government seems unwilling to offer even an honest assessment of the carnage, much less take any action.

For Kiir, months of international inaction have allowed his regime to operate unchecked. “The Obama Administration was very rough with the government of South Sudan,” Ateny Wek Ateny told me. “President Kiir hopes that the Trump Administration will be different, given that the Trump Administration will be focusing on making America great again and therefore will be reducing interference in other countries’ affairs.”

One afternoon in February, a mile or two from the Laufori collection point in Uganda, I met Salina Sunday, a thirty-eight-year-old resident of Bamurye and chair of the local women’s chapter of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement, Kiir’s political party. When S.P.L.A. troops began killing civilians in Bamurye, Sunday left town with Alex Kajoba, the village elder whom Simon Yakida and the S.P.L.A. officer referred to as Abu Sala.

Soon after they reached the border, both decided to head back to their village, hoping to salvage whatever belongings they could. Kajoba took one path back, Sunday another. She made it back to Uganda. He didn’t.

Sunday told me she could take me to see Kajoba, but it meant crossing the border, traveling within earshot of the Bamurye barracks.

We spoke with dozens of drivers who refused, saying that the journey to Bamurye meant certain death. Finally I found a young man and negotiated a price. For forty minutes, we rode hell-for-leather—three of us on an overloaded motorcycle—down narrow, rutted footpaths to reach the outskirts of Bamurye.

I spotted Alex Kajoba—husband, father, grandfather—lying on the roadside at the edge of town, where multiple villagers, including Simon Yakida, said they had last seen him. His body was blackened and bloated, reeking of the sweet, terrible scent of putrescence, his stomach bursting out of his tan shirt. His hands were missing. What remained was a bloody stump on the right, a jagged shard of bone jutting from torn flesh on the left. His head was gone. Where it had met his neck was alive with a writhing mass of maggots spreading down his chest.

“After killing Abu Sala, they tried to shoot his wife. Fortunately, she was able to run and hide in the bush. They took his money and his bicycle,” Jackson Milla, thirty-seven, told me. The soldiers shot Kajoba in the side, then executed him, firing a bullet through the back of his head. Later they returned to defile his corpse, leaving the mutilated man as a warning to others.

It’s impossible to know just how many civilians in the Equatorias have been killed, but the indicators are staggering. “A hundred and twenty thousand South Sudanese refugees poured into Uganda in just the first two months of this year,” Yasmin Sooka said. “Almost all of them, when interviewed, said they had witnessed someone close to them being killed.”

In the face of this immense bloodshed, the government’s response has been remarkably cavalier. “If the Sudan People’s Liberation Army were killing people, there wouldn’t be any civilians left in South Sudan right now. We would have finished them off,” Ateny Wek Ateny told me.

In fact, analysts believe that something similar is happening. “There will be nobody left in South Sudan shortly,” Kate Knopf, the Pentagon expert, told me. “Either they will be dead, or they will have fled.” Her husband, Payton Knopf, until recently the coordinator of the U.N. Panel of Experts on South Sudan, said that by the end of the year, the country is projected to lose half of its population—counting only those who flee and those likely to die of starvation. “That’s an extraordinary and very rare thing,” he told me. “By comparison, in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, about a third of the people were killed—and that was an indisputable genocide.”

Facing the unimaginable, South Sudanese asked me why the international community—especially the United States—hadn’t come to their aid. “If this message can reach Donald Trump, ask him to come and see the situation in South Sudan. Let him come and see us living outside under trees,” said fifty-six-year-old Rkangelo Gbado Naakpurakondo, who fled to Yambio when his village, Gitikiri, was attacked by the S.P.L.A. in January.

I explained that Trump was pursuing an “America First” agenda, hoping to temporarily halt and then severely cut the number of refugees entering the United States. His plans, if approved by Congress, would slash the 1 percent of the budget previously devoted to foreign aid, cutting contributions to the U.N.’s peacekeeping funds while reducing support for overseas humanitarian organizations. The money saved might even be earmarked to build a wall to keep people out of the United States.

Naakpurakondo told me he believed that the United States could save his country—or at least be his own personal salvation. “If we had wings like birds, we would fly to America,” he said. “And we would stay there until peace finally comes to South Sudan.”