Discussed in this essay:

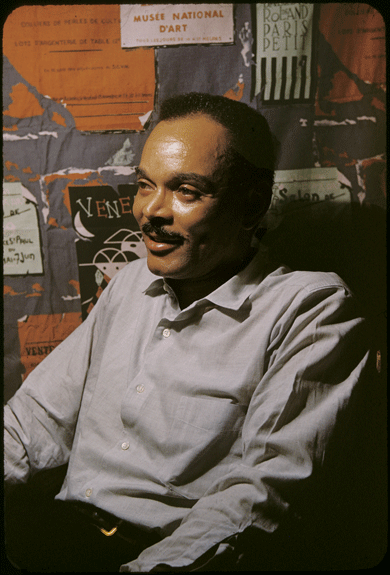

Chester B. Himes: A Biography, by Lawrence P. Jackson. W. W. Norton. 640 pages. $35.

Early in Chester Himes’s first and best-known novel, If He Hollers Let Him Go (1945), the brown-skinned narrator, Bob, takes his light-skinned love interest, Alice, on a surprise date to a fancy hotel restaurant. Alice is a member of the black bourgeoisie, the daughter of a prominent physician; Bob is working-class, a leaderman at a Los Angeles shipyard. As he pulls his Buick up to the restaurant, her resistance leads him to suspect that Alice, a social climber, may have dined there in the past with whites who didn’t know she was black. But he forces her inside with the brutal calm of a man accepting a duel he is certain to lose. The two are seated at the worst table in the house, next to the kitchen door, and duly disrespected by the waitstaff. Powerless against the mounting humiliation, Bob lashes out. “I thought you liked places like this?” he says to Alice. The evening is an exercise in sadomasochism as torturous as anything in Dostoevsky. When the bill arrives, it reads: “We served you this time but we do not want your patronage in the future.”

The scene does more, however, than hold up a mirror to American skin prejudice. Himes is an artist of unusual, discomforting candor, whose eye for the psychological contradictions of membership in a lower caste is sharper than that of any American writer before or since. During the meal, Bob glances over to the next table, where a young ensign is sitting with a beautiful blonde. He looks at her longingly for a moment before his eyes meet those of her companion:

The scene does more, however, than hold up a mirror to American skin prejudice. Himes is an artist of unusual, discomforting candor, whose eye for the psychological contradictions of membership in a lower caste is sharper than that of any American writer before or since. During the meal, Bob glances over to the next table, where a young ensign is sitting with a beautiful blonde. He looks at her longingly for a moment before his eyes meet those of her companion:

There was no animosity in his gaze, only a mild surprise and a sharp interest. There were two elderly people at the table, probably the parents of one of them, and the man laughed suddenly at something that was said. After a moment he switched his gaze to Alice; it stayed on her so long the blond girl looked at her too. Her face kept the same expression. Alice didn’t notice either of them; she was drinking her martini with a rigid concentration.

I had a sudden wistful desire to be the young ensign’s friend.

This is quintessential Himes: a rage that burns so hot it melts into a kind of perverse love.

If He Hollers — at turns savage and startling, illuminating and wise — charts an abysmal four-day span in Bob’s relatively privileged life, during which he slaps Alice, murderously stalks one white co-worker, and comes unhinged at the opportunity to punish-fuck another. As Himes said in “The Dilemma of the Negro Writer in America,” a speech he delivered in 1948,

If this plumbing for the truth reveals within the Negro personality homicidal mania, lust for white women, a pathetic sense of inferiority, paradoxical anti-Semitism, arrogance, Uncle Tomism, hate and fear of self-hate, this then is the effect of oppression on the human personality.

Yet what makes If He Hollers not merely a protest novel but a work of art — a book that in its unrelenting dejection and absurdity calls to mind Sartre’s Nausea and Camus’s The Stranger — is that for all the prejudice Bob faces, it’s ultimately impossible to say whether social forces or his own bad decisions are to blame for his implosion. At the time the book came out, white readers and publishers had recently made a star of Richard Wright for Native Son (1940), the blunt, deterministic story of a barbaric black man who murders a white woman, and they would soon catapult the patrician Ralph Ellison into the literary firmament for Invisible Man (1952), his exquisite meditation on the social anonymity of black Americans. But they had never encountered anything quite like Himes’s feverish vision of lustful ressentiment. Seven decades after the book’s publication, at a moment when the repeated spectacle of black men being killed by police has forced many of them to assert something as basic as the idea that their lives matter, its insistence on black culpability as well as victimization remains difficult to assimilate. Still, the questions that obsessed Himes — about the psychological toll of being “black” and, perhaps more crucially, of not being “white” — feel as urgent as they ever have.

The rediscovery and near sanctification of James Baldwin — kicked into high gear in 2015 with Ta-Nehisi Coates’s memoir Between the World and Me and intensified at the end of last year with Raoul Peck’s documentary I Am Not Your Negro — has provided as powerful a framework to understand the continuity of what used to be called the “Negro problem” as we are likely to come across. At the same time, it has had the odd effect of simultaneously expanding and narrowing our debate over race. This is in part the result of what Henry Louis Gates Jr. has called “the ethnographic fallacy, the pretense that one writer’s peculiar experiences can represent a social genus.” Baldwin, remarkable as he was, can never serve as a comprehensive lens, something his ubiquity in the marketplace of ideas has now made plain.

A selective interpretation of his work has exacerbated the problem. In the conversation around Between the World and Me, Coates was initially positioned as the new Baldwin. Yet it often feels as if Baldwin has been retrofitted into something akin to the original Coates — a militant proto-ambassador of “wokeness,” an eloquent victim. In such a neat reconstruction there is little use for the messiness and contradictions of real life. So the time feels ripe for an exploration of different, less manipulated voices — a broader reevaluation of the offerings of that most fertile period in African-American cultural production, and of its continued relevance to our own. Fortunately, we now have the exhaustive and fascinating biography Chester B. Himes, in which Lawrence P. Jackson, a professor of English and history at Johns Hopkins University and the author of a well-regarded study of Ellison, makes the case that we have every reason to reimagine that trio of great black postwar novelists — Baldwin, Ellison, and Wright — as a quartet.

The world has never known what to do with black men like Chester Bomar Himes. And Himes, as Jackson suggests, never really knew what to do with himself, either. He was born to a middle-class family in Jackson City, Missouri, in 1909. His parents were home-owning, upwardly mobile teachers, a remarkable feat considering they were only one generation removed from chattel slavery. Unlike Himes’s dark-skinned father, Joseph, his white-looking mother, Estelle, seems never to have fully acclimated herself to the social reality of being black. She once told her children, “You mustn’t think of yourself as colored. Your mother is as white as anyone. You both have white blood — fine white blood — in your veins. And never forget it.” This “willful intention to ignore racial barriers and proclaim as true her fantasy heritage,” as Jackson puts it, seems to have had a disastrous effect on her youngest son. Although he could never hope to pass, and likely wouldn’t have wanted to, Himes aspired throughout his life to a postracial state of absolute acceptance among whites. It was perhaps his defining feature on and off the page, and an inexhaustible source of frustration.

The Himes family moved frequently during Chester’s youth, in pursuit of better jobs and homes, as well as in retreat from stifling racism. In 1914, they left Missouri for Lorman, Mississippi, where Joseph had secured a post as a professor of blacksmithing at segregated Alcorn College. Himes picked up a Mississippi accent that, though he never lived there again, he kept for the rest of his life. This must have distressed Estelle, who was determined to prevent her children from turning “vulgar.” To keep blackness — or at least her limited sense of it — at arm’s length, she homeschooled her sons, playing Chopin and Verdi on the piano and reading from volumes of Greek and Roman mythology at night. She also rigorously restricted their contact with the neighbors, including the children of other faculty.

By 1923, the Himeses were living in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, where the first in a series of catastrophes definitively altered their upward path. During commencement-week exercises at their high school, Chester and his older brother Joe Jr. were scheduled to make gunpowder onstage. Though he always denied it, Chester seems to have lost his nerve and allowed his brother to go it alone. Joe Jr. miscalculated the formula, and the beaker exploded in his face, severely injuring his eyes. Doctors at the city’s main hospital refused to treat him because he was black. The boys’ father wept and pleaded — one of many emasculations his family would witness — but they were forced to go to the black hospital, where the necessary surgery was unfeasible; all the doctors could do was dress the wounds.

Estelle and Joe Jr. went to St. Louis for months of long-term care, while Chester remained with his father in Pine Bluff. When the family reassembled in Missouri, Joseph, having given up his faculty position in a dying field, was reduced to manual labor (a move that foreshadowed what was in store for his son). “He was a pathetic figure coming home from work,” Himes wrote in his autobiographical novel The Third Generation (1954). “A small black man hunched over and frowning, shambling in a tired-footed walk, crushed old cap pulled down over his tired, glazed eyes, a cigarette dangling from loose lips.” The family moved on to Cleveland, where Chester, who had received a drastically uneven education in the South, graduated from high school in 1925 only by the grace of a clerical typo. Nonetheless, he enrolled at Ohio State, ostensibly with the intent of becoming a medical doctor.

Jackson, a fluid writer who has published vivid first-person essays in this magazine, mostly restrains himself here, allowing the startling facts of his subject’s life to speak for themselves. But if there is a flaw in the book, it is Jackson’s reliance on a somewhat pat determinism; the gender and color dynamics of Himes’s childhood home are too readily invoked to explain his behavior as an adult. While the writer’s relationship to his parents was certainly fraught, neither this nor the racism they all experienced entirely accounts for his unique trajectory. No other writer so fully embodies or conveys in his work the agency problem of modern black life. Himes, as both an artist and a man, forces us to rethink the degree to which black people live in reaction to oppression yet may also elect to be complicit in it.

For reasons that Jackson’s book does not — and perhaps cannot — make clear, Himes was simply allergic to the respectability politics of his mother and his privileged extended family, many of whom exemplified Du Bois’s talented tenth. Even as his blind brother set off on a career of scholastic achievement (from high school valedictorian to magna cum laude at Oberlin to tenure at the all-white University of North Carolina at Greensboro), Chester displayed a remarkable predisposition to the pleasures of the street. The summer before Himes started at Ohio State, his father found him a bellhop job at a luxury hotel. He took his first paycheck straight to the red-light district and lost his virginity to “an old fat ugly whore sitting on a stool outside her hovel.” Just two weeks into the job, in a move that in a novel would feel didactic, he stepped backward into an open elevator shaft while flirting with some white girls. “He fell two stories,” Jackson writes, “shattering his chin and jaw, his left arm, which he used to break his fall, his pelvis, and three vertebrae.” Himes compared the impact to “spattering open like a ripe watermelon.” Like his brother, he was turned away from the best hospital in the area. Newly established workman’s compensation laws, however, meant that Himes began receiving seventy-five dollars a month, an amount equal to his father’s highest pay.

Nearly an invalid but suddenly flush, Himes developed a taste for hookers and bootleg liquor, inching deeper into Cleveland’s thriving Prohibition-era underworld. By autumn he’d recuperated enough to drive himself (in a Model T) to Ohio State, where he placed fourth among the incoming freshmen on an I.Q. test. But the easy money seems to have ruined him for school. He eschewed the courtship rituals of his classmates and took up with a prostitute named Rose, from whom he contracted gonorrhea. In the classroom, he submitted a blank paper for his German final and got into a fistfight with his chemistry T.A. When he returned during the winter semester, on academic probation, he escorted a group of black couples from a formal dance to Rose’s brothel, where she confronted his date and was viciously beaten by her pimp. Himes was quietly expelled.

Back in Cleveland he impregnated a girl (it’s unclear if she ever had the child; either way, he was not involved) and swiftly fell under the sway of a paternal hustler. The man initiated Himes into the fast life, showing him how to flip his disability checks at illicit casinos. “Chester’s own father was pushing a broom at a joint called the Sixty Club from midnight to eight in the morning,” Jackson writes. “The tragedy of the black college teacher whose son could not finish a quarter in good academic standing and was imitating local gangsters was complete.”

After a series of petty crimes, Himes eventually landed in county jail. Out on probation, watching his parents’ marriage dissolve in no small measure because of him, he and two accomplices robbed the National Guard Armory of “a cache of .45 automatic pistols” before looting a furrier. They were arrested while off-loading the goods. Remarkably, instead of being railroaded by the draconian criminal justice system, Himes got away with the caper: A sympathetic white judge paroled him. But he made a mockery of her leniency. One month later, he broke into the home of a wealthy white family and stole four rings worth about five thousand dollars. He fled in the couple’s Cadillac before hopping a train to Chicago. “He was arrested in a pawnshop trying to sell the jewelry the next day,” Jackson writes, “and hung upside down and beaten on his testicles until he confessed.” In 1928, at the age of nineteen, he was sentenced to a minimum of twenty years at the other Ohio State.

It’s hard to know whether Himes would have become a writer were it not for his time behind bars. Nothing in Jackson’s book, or in Himes’s own body of work (seventeen novels, a collection of drama and stories, and two volumes of autobiography), leads to that conclusion. His literary voice seems to have been unlocked by confinement. The conditions were brutal for all — there were three times as many men as the building had been built to hold — but especially for blacks, who were given the hardest work assignments, at a local coal company, and tasked with cleaning out the prison latrines. Ever fortunate in his misfortune, however, Himes was exempted from manual labor on account of his broken back and assumed the role of observer.

In April 1930, one of the deadliest fires in American history ripped through the cellblocks, killing 322 trapped men and leaving in its wake a temporary Gomorrah. Inmates “high on diluted ether purloined from the penitentiary hospital” refused to stay in their cells. “They had sex, shot dice, and played Cab Calloway on the organ in the chapel.” One convict constructed a makeshift strip-show with a curtained-off bordello. The National Guard had to be called in to put down the insurrection. Around this time, Himes began engaging in what the biography terms “situational” homosexuality.

As Jackson writes, “The personal tragedy of incarceration, loneliness, physical vulnerability, the conflict of homosexual desire, and the gruesome slush of human entrails in the yard” sparked Himes’s writing career. He composed stories of prison life that combined artistic ambition with earnest commercial appeal while keeping his style malleable enough to suit a variety of publications. He sent work “in bundles” to black venues, especially Abbott’s Monthly, a prestigious and short-lived journal that was publishing Richard Wright and Langston Hughes. That Himes was capable of producing viable fiction under such circumstances is deeply impressive, and yet, as Jackson points out, he enjoyed several undeniable advantages over other aspiring black — and white — writers of the Depression era: “a roof overhead, three daily meals, and plenty of time” to think and create. He also had a muse — an inmate named Rico, whose letters he never discarded. “I was in love with him more, perhaps, than I have ever been in love with anyone before or since,” Himes later confessed.

Increasingly ambitious, and savvy — “he knew that American whites wished to read about themselves” — Himes began sending stories featuring white protagonists to Esquire. Some three decades before the publication of Giovanni’s Room, Himes was mining his own reality to compose fiction from a non-black point of view while also tackling homosexual themes. His first piece for Esquire, “To What Red Hell,” re-creates the terror of the 1930 inferno:

Smoke rolled up from the burning cell block in black, fire-tinged waves. The wind caught it and pushed it down over the prison yard like a thick, gray shroud, so low you could reach up and touch it with your right hand.

In such dire circumstances, the tyranny of racial difference attenuates (all men burn alike) — an insight that allowed Himes to gesture at the kind of racial unity that was all but impossible on the outside.

After serving just eight years, Himes benefited from a bill to reduce overcrowding in Ohio’s prison system and was released back into the world, a fully formed, nationally published writer at the age of twenty-six. But once free, he struggled to maintain his momentum — he was to spend ten years laboring on a tell-all prison novel, Yesterday Will Make You Cry, that would not be published in its entirety until 1998. He was perpetually on the cusp without ever making his name. Although Esquire continued to purchase his work sporadically, he was less interesting to them as a free man.

There were other challenges as well. Seeking to stifle his gay desires, he quickly married a pretty, loyal girl named Jean, with whom he’d briefly shared an apartment as a teenager. (He had casually passed her off to an acquaintance before his arrest.) With Jean, Himes lived as oddball and peripatetic a literary existence as Jack London or Roberto Bolaño. He oscillated between the need to see himself as a patriarch — often taking soul-crushing menial jobs to support them — and living off her earnings as an office worker. In Ohio, Himes waited tables at country clubs, dug ditches for the WPA, and was a servant at the writer Louis Bromfield’s farm. In California, he found unionized employment in the defense industry (grist for If He Hollers as well as his second, anti-Communist novel, Lonely Crusade) and at the California Sanitary Canning Company, as well as securing the occasional prestigious literary fellowship. In New York, he mopped cafeteria floors, operated switchboards, and regularly drank himself into a stupor. “The irony of being financially better off and more successful as a short story writer while an inmate,” Jackson notes, “was easy to see but hard to accept.” He also developed the habit of cheating on Jean. Their reversal of traditional gender roles bothered him, and reinforced one of his defining characteristics: an abject misogyny that was trained most ferociously on black women.

Despite all this chaos, he somehow managed to get a lot of writing done, and to secure book deals at the most prestigious imprints in the country. But it wasn’t the deliverance he’d imagined. While Himes was in prison, Jackson observes, he had “focused his attention so sharply on release” that he’d almost forgotten he was black. (“Until then, there had been nothing racial about my hurt, unbelievable as this may seem,” Himes wrote in his memoir The Quality of Hurt.) The white-shoe world of letters provided him with ample opportunity to revise that view. The critical reception of If He Hollers was largely positive from black and white readers alike — seeing the continuation of his sensibility, Wright was effusive, and the Cleveland Plain Dealer called it “the ticket-of-admission of Chester B. Himes to the limited company of our top-flight novelists” — but the subject matter proved radioactive. His own publisher, Doubleday, sabotaged the book. Its dust jacket embarrassingly stated: “What he writes comes from firsthand information rather than from a fertile imagination.” The house went as far as taking out an advertisement in the Saturday Review of Literature comparing Himes’s book unfavorably with a competing story of racial uplift.

But life among the literary classes had its perks. Himes won the approval of white tastemakers like Carl Van Vechten and the affections of politically liberal, culturally sophisticated white women like Vandi Haygood, his on-and-off mistress throughout the Fifties. Haygood was the first but not the last white woman he beat up with the force of a sadomasochistic love every bit as perverse as Bob’s in If He Hollers; later, in times of contrition, he would plead forgiveness, referring to himself as a “dirty nigger.” “The first thing I desired now that I had money,” Himes once remarked to an interviewer about the feeling of receiving a desperately needed advance, “was to sleep with a white woman.” Ever the critic of black matriarchy, though increasingly willing to live off the pity and generosity of wealthy whites, he nominally split from Jean in 1952, blaming her successful career as a U.S.O. organizer — which had in large measure made his early writing possible — for the dissolution of their marriage. Though he enjoyed a series of intense affairs over the final thirty years of his life, Himes would never have a relationship with a black woman again.

In 1953, with the help and encouragement of Richard Wright, who had gone into self-imposed exile several years earlier, Himes sailed to Paris, where his novels, all of which bombed domestically, had been favorably received. Aside from one brief stint back Stateside, he lived in Europe, mainly in France and Spain, for the rest of his life.

At a remove from the American racial caste system and the artistic imperative to protest against it, and already attuned to black aesthetics through the G.I.-fueled jazz scene and pastiche such as Boris Vian’s novels in blackface, French critics and audiences brought vastly different expectations to African-American literature. They also showed a straightforward appreciation for a variety of purportedly lowbrow American genres, such as westerns and detective fiction. Soon, Marcel Duhamel, a powerful figure at the publishing house Gallimard, suggested that Himes try his hand at crime stories. Himes felt such work to be beneath him but urgently needed the income. Eventually, he conceived a series of policiers set in Harlem. In a seeming demotion that echoed his previous lapses into menial labor, he soon accepted that his literary career was behind him and took to detective fiction with relish.

As in prison, he flourished under constraint. The narrowness of the form, Jackson notes, allowed him “to create sizzling exaggerations that amplified and telescoped his concerns” about the black Americans he described as “the most neurotic, complicated, schizophrenic, unanalyzed, anthropologically advanced specimen of mankind in the history of the world.” And so it was that detectives Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson, the antiheroic center of Himes’s writing for the next dozen years, eventually brought him the wealth and status he so badly craved — first in Europe and later in the United States.

Reviewing the sixth novel in the series, Cotton Comes to Harlem, in 1965, the Los Angeles Times argued, “More important than its entertainment value is the social comment it makes throughout,” in particular its simultaneously compassionate and withering depiction of a Garveyite back-to-Africa scheme. Himes, however, downplayed any nobler motivations. At a dinner party, Jackson writes, “Chester told the crowd that he had not even a dilettante’s concern about the quality of his art or its political dimensions. ‘I don’t write for money accidentally,’ he lectured, ‘it’s my main purpose.’ ” This seems a lot more like the hard-won gloating of a man who had finally made his intellectual labor pay than any genuine modus operandi. In any event, he understood that it was far too late to make himself respectable.

Decades of heavy drinking and drug use, compounded by scarcity and stress, began to take their toll by the Seventies, when Himes suffered two debilitating strokes. But — at least as he liked to tell it — he’d “become more famous in Paris than any black American who had ever lived.” He had arguably bested Baldwin, whose own worldview, Jackson claims, grew ever more Himesian as he found himself “held in decreasing esteem” over the final twenty years of his career owing to the tumult of the Sixties and the rise of Black Power. Ironically, since Himes evinced none of the latter’s desire to be a spokesman, his own standing among the younger, more radical generations only grew stronger.

It made no difference, for his would always be a one-man movement. This is perhaps his most intriguing legacy for the present: the possibility of an uncompromisingly personal liberation. Whether or not black lives in the abstract could be said to matter no longer concerned him, if it ever had; Himes was determined to make sure his own life did. And though he would eventually swap the girl and the car for English models and retire to the warmer climes of Spain, his reason for settling in France remained the same until his death, in 1984: “I had a German girl, a German car; I was making my living from French publishers, and I had no reason whatsoever to put foot in America.”