I. THE HIGH DESERT

Someone told me I could find a reclaimed uranium mill in Tuba City, so I drove up from Flagstaff through the Arizona badlands. The town was easy to find. It sits along the only major east–west corridor of the Navajo Nation, an area roughly the size of Panama but immeasurably lonelier and therefore, in the mind, vaster. There are ten grocery stores for more than 200,000 people, most of whom live in arid, unpaved hamlets that wink in and out of view from passing cars. Turkey vultures ride the currents above layer-cake hills of shale and silt.

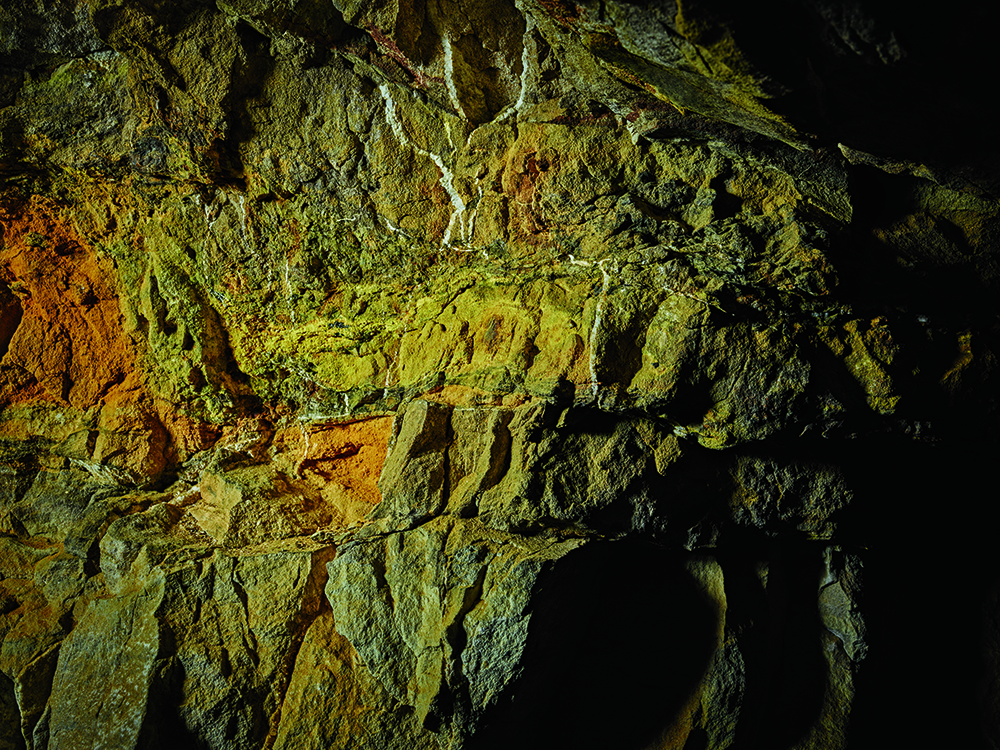

Uranium ore in the abandoned Hummer Mine, Paradox Valley, Colorado (detail). All photographs by Balazs Gardi

My waitress at the Tuba City Denny’s was too young to remember the mill in operation, much less the years when lung cancer was exceptionally rare among the Navajo rather than a leading cause of death, but she told me it was probably somewhere east of town. After parking along the highway and hiking into the desert, I found it: a field of uniform black rocks, like some glinting alien moonscape. Yellow signs were blazoned with the traditional hazard symbol for ionizing radiation. One indicated that beneath this engineered mound were 2.25 million tons of mill waste, most of it the pulverized rock slurry that is a byproduct of making yellowcake, and which will exhale clouds of radon gas for a fair approximation of eternity. The slurry is interred in impoundments and protected by an elaborate system of layered sand, soil, and rock, where it will sit for thousands of years. There are often complications. Tuba City’s cleanup is not yet thirty years old, but waste is already leaking into the aquifer beneath the site. Nor could the area be called uninhabited, even if the nearest homes were sagebrushlike specks on a distant slope. Just outside the perimeter fence, sun-faded beer cans and scorched asterisks marked the campsites of heedless drifters.

I spent the night farther north, in Blanding, a dry town with three Mormon churches. In the morning I stopped in at Hunt’s Trading Post, which advertised native crafts and espresso. The owner, Debbi, chatted while I browsed the turquoise. Nearby Hunts Mesa was named for her father. “He did some prospecting up there,” she said. “Everybody in Blanding has a father or an uncle who did. Nobody knew anything about radiation back then.”

Debbi and her family were downwinders. Radioactive ash from test sites in Nevada had snowed across the reservation and the Four Corners in the Fifties and Sixties. Dairy yields in those days were rich in iodine-131. “I could’ve gotten some money,” she said of the lawsuits that followed, “but I didn’t want the hassle.” Her aunt and several cousins had breast cancer, but Debbi reckoned that the men had gotten the worst of it, particularly the thousands of Navajo miners who served as canary labor for military contractors and the first uranium barons. They started dying off in droves in the Seventies.

Still, it had been good work if you could get it, she said. “At the time we thought, ‘It’s just rocks.’ ”

In the beginning, or close to it, the Colorado Plateau was pretty much just rocks, a Proterozoic crust roamed by the first few animals and washed by tropical seas. Over hundreds of millions of years, these waters deposited strata of sand and grit atop the igneous bedrock. A bit later — some 75 million years ago — a tectonic event known as the Laramide orogeny formed the Rockies and lifted the plateau, a thick unbroken shelf, a mile above sea level. Salt domes collapsed and rivers deepened their courses, carving out the gulches, hoodoos, and buttes of Hollywood westerns. The panorama of carbon-based life wheeled on, living and dying, falling into lightless caverns and bearing fossilized witness to the precipitation of a metal formed inside supernovas, a metal so heavy it does not want to exist. “Uranium,” from Uranus, child of Gaia, father of Titans.

Aerial view of Energy Fuels’ White Mesa mill, near Blanding, Utah

For the bulk of human history, the uranium lay in the ground where it had settled. Then, on December 2, 1942, the Italian war émigré Enrico Fermi demonstrated the direct conversion of matter into energy on a squash court at the University of Chicago. The so-called Chicago Pile was the first nuclear reactor, proof of concept for the power plant and atomic bomb.

The first yellowcake towns appeared in the American West the next year, as Colorado miners became participants in a top-secret project for the Army’s nonexistent Manhattan Engineer District. The miners had no idea what the uranium — an unprofitable ceramics dye — was to be used for. But thanks to their efforts a new genre of ruination befell Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and after the war, the Atomic Energy Commission was formed to shore up our domestic stockpile. As politicians turned their attentions toward the new Soviet menace, the country was informed that finding and processing atomic fuel was its patriotic duty.

The A.E.C. lured prospectors out West with inflated buying rates and discovery bonuses. They drew maps, built supply roads, and flew survey planes equipped with radiation detectors — did everything but the digging itself, which they hoped to outsource to modern-day Klondikers. It worked. With a single buyer and a guaranteed market, uranium procurement was the only deal of its kind ever made in the United States. Thousands descended on sleepy frontier towns like Moab, in Utah, and Grants, in New Mexico. Hardscrabble ranchers combed their ravines with department-store Geiger counters. A dubious penny-stock market in staked claims attracted venture capitalists and Mormon housewives. Most of the wildcatters went broke, but a lucky few became uraniumaires and had their mining boots cast in bronze. They dug four thousand mines into the plateau, the largest of which — the Orphan — still receives some 4.5 million visitors a year, having been built directly into the cliff side of Grand Canyon National Park.

In those years there was no claim too far-fetched for America’s impending energy utopia. “Furnaces of vest-pocket size,” one newspaper predicted. “Power for whole cities produced from a few handfuls of matter.” The chairman of the A.E.C. told a group of science writers that electrical energy would become “too cheap to meter.” Even Alvin Weinberg, the otherwise staid architect of the nuclear power industry, dared to speculate that we might soon arrive at “an ultimate world of 15 billion people, living at something like the current U.S. standard” on 300 billion kilowatts of fissioned heat.

Havasupai tribal elders pray during a protest against planned uranium mining and transport, near the Canyon Mine, Red Butte, Arizona

Last September, I rented a midsize car for a two-week trip across the Colorado Plateau. I wanted to visit what was left of our country’s brief atomic romance. What had happened to the thousands of mines and the dozens of processing mills? The yellowcake towns? I knew that domestic uranium production had become a deeply enervated industry, contrary to all those predictions. The A.E.C. killed its procurement program in 1970, the same year that the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons went into effect, and in 1974, the government ended its monopoly on enrichment, inviting foreign competition. The partial meltdown at Three Mile Island kiboshed the construction of dozens of power plants, and as downwinders and miners reached middle age, cancer clusters sprouted across the plateau. Mines fell dormant. By the time the Cold War came to an end and plutonium from decommissioned Soviet nukes flooded the market with cheap fuel, the industry was dead.

Yet the stuff is still out there, waiting out the cycles of speculation that keep the industry in a state of suspended animation, and much of America’s boom-age infrastructure remains on standby. In 2007, uranium ore prices briefly shot up to more than $130 a pound, causing a flurry of investment. Companies began redeveloping mines across the plateau, including the Canyon, a shaft mine a few miles from the Grand Canyon in a protected forest of aspen and piñon pine. The Canyon is owned by a uranium-production company called Energy Fuels and is one of just a handful of operating mines left in the country — “a zombie come back to life,” as one conservationist described it to me. Licensed zombies with confirmed ore bodies are exempt from an ongoing twenty-year mineral withdrawal from the greater Grand Canyon area. When I visited, a chute attached to the headframe was spitting out rocks and dust. The miners expect to hit ore in the coming months.

Whatever happens at the Grand Canyon, uranium’s spot price remains too dismal for commercial prospecting. Last year’s domestic production was the lowest in more than a decade. Yet miners at the Canyon Mine continue to dig, having locked in above-market rates. Energy Fuels argues that new regulations and voluntary monitoring will prevent the kind of contamination that has polluted rivers and old mine sites across the plateau. But this past April, the Canyon’s shaft began to fill with uranium-rich groundwater that had to be pumped to the surface and sprayed out over a containment pond that abuts Kaibab National Forest. Conservationists worry that the unprofitable energy company won’t be around to protect the area’s underground streams from similar incidents in the more distant future. Uranium-238 has a half-life of 4.5 billion years.

II. THE LAST URANIUM MILL

At one time, there were twenty-eight operational mills like Tuba City’s around the country, refining raw uranium ore into yellowcake. Today there is one. The moribund heart of the uranium boom beats in White Mesa, Utah, an unincorporated town of about three hundred Ute Mountain Utes north of the San Juan River. Driving through White Mesa, I passed weatherworn trailers, pickup trucks on concrete masonry units, and dilapidated shotgun houses whose driveways showcased pristine A.T.V.’s. A few miles outside town, America’s last conventional uranium mill was just visible from the highway.

When the mill is processing ore, as it was during my visit, it operates twenty-four hours a day, and a sour odor wafts through the downwind trailer parks. At other times, the mill processes what is known as alternate feed, i.e., waste from other processing facilities, Manhattan Project sites, and Superfund cleanups. This is good stopgap business for the mill, and a handy way for other companies to pass on their unwanted waste. Mill workers describe it as a kind of recycling: recovering natural uranium from unconventional sources. Critics say the mill is acting as an ad hoc dump for types of toxic waste it was not designed to manage.

Thelma Whiskers at her home, White Mesa, Utah

I went to a tribal hearing about the mill at the White Mesa Community Center, where a sign posted outside warned me that I would be ejected if my breath smelled of alcohol. Inside, about fifty locals ate burgers and hot dogs at picnic tables that had been set up in a gym. Half were White Mesa locals, which is to say, members of the Ute tribe sponsoring the event; the other half were Anglo hippies who’d retired to the artists’ enclave next door in Bluff. (“We chose Bluff to avoid radioactivity,” a petroglyph enthusiast from Denver told me.) When an organizer polled the audience, only the two men next to me, both in half-zips and denim, identified themselves as local to Blanding, the blue-collar town where many of the mill’s employees live.

The meeting lasted three hours. The tribe’s environmental director described a host of problems they’d found with the mill: that the vinyl linings of its impoundments were thin, outdated, and prone to leaking; that the groundwater in the shallow aquifer beneath the mill contained plumes of nitrates and other “smoking guns” of uranium waste; that incoming trucks had more than once spilled radioactive waste onto the highway bisecting the town; that the mill had failed to prepare sufficient funds for reclamation, virtually guaranteeing that it would become a Superfund site.1 Appended to this grim account were suggestions for regulation and voluntary reform.

David Yearicks, a White Mesa handyman, had had enough. He stood up. “So basically you’re saying the mill is going to continue to operate and we’re going to have to deal with the contamination? Is that what you’re saying?”

Silence filled the gym. “I don’t know,” the director said. “That’s where we’re at right now.”

“So what’s going to happen? Nothing?”

Children at a skate park, Tuba City, Arizona

One by one, others stood to speak. They described foul-smelling tap water and suspicious deaths of wild animals. They wanted closure, not reform. “I’ve been fighting the White Mesa mill for years, years, years,” said Thelma Whiskers, a tribal elder. Her fellow activists were old or dead. She recalled thinking a few years ago that the mill had closed for good, only to see smoke rising from its silhouette a few months later. Now she began banging on the bleachers in frustration, emphasizing every other word. “Why can’t they listen to us people here that live on this Ute reservation? My people are sick! And they won’t listen!” After the meeting, David told me that he thought that the whole town should probably relocate. You just can’t fight these corporations, he said. There’s too much money and power involved.

During a lull between speakers, the Blanding man next to me had introduced himself. His name was Logan Shumway, he said, and his family had settled Utah with the Hole-in-the-Rock pioneers. He handed me a business card identifying him as an Energy Fuels engineer. “What you heard tonight is pretty crazy,” he whispered. “If you want to get the real story, give me a call.”

Two days later, I passed through a glass security door into the White Mesa Mill. In a conference room lined with maps and aerial photographs, Logan dismissed much of what I’d heard the other night. Yes, they’d had some damaged liners — no liner holds up forever, he said — but they had quickly replaced them with new, thicker liners, to the tune of hundreds of thousands of dollars. They also monitored groundwater and air quality at about a hundred locations all over their property. The land was naturally uranium-rich, so Logan felt that many allegations of contamination were unfounded. He pointed out that the mill was currently in full compliance with all regulatory agencies, and that research by the state of Utah had not determined that the mill was to blame. Environmentalists always neglected to mention these facts. “A lot of the stuff they said at that meeting, they know what they’re doing,” he said. “But it’s half-truths said in a way to scare the heck out of you.”

From a cabinet he pulled out a glass jar of yellowcake. “I deal with this stuff every day,” he said. “I mean, you don’t want to lick it or eat it, but I wouldn’t want to lick a lot of things.” Both of Logan’s grandfathers had mined uranium. One had even managed the land deal for the mill’s original owner. The other, he said, was Calvin Black.

Lucas Hixson measures radiation in front of the SM-18 uranium mine, near Uravan, Colorado, a former Manhattan Project company town

Cal Black was an infamous industry strongman who made a small fortune in the A.E.C. years. I’d read that he liked to wear a bolo tie fastened with a uranium medallion in order to dispel sissy rumors about the metal’s health hazards. (He eventually developed lung cancer and tumors on his clavicle.) A red-blooded cowboy tycoon, Black had tried to build a nuclear waste disposal site near Canyonlands National Park, for which service he was fictionalized as the wicked Bishop Love in Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang.

Uranium was the family business, Logan explained, and a safe one. I asked him whether he thought any reforms might satisfy the groups from the meeting. He didn’t think so. They would only be happy when the mill closed and his town was out of work. I pointed out that it would probably be easier to ship the industry overseas to Kazakhstan, where safety and environmental regulations were less stringent. He agreed, and said it was hard to take such shortsighted efforts by environmentalists at face value; in effect, they were shifting the costs of American energy consumption elsewhere. Uranium processing didn’t get any safer or cleaner than right here in the United States. I told him I saw his point. “Can we see the work site?” I asked.

He found me a hard hat and we went out to a dusty plot beneath metal tanks of leaching acid. A few dozen black drums stood against a wall in serried rows. “That’s yellowcake,” he said. An evaporation pool shimmered darkly in the distance.

Per federal requirement, we ran an alpha-meter probe over our limbs when we came inside. The needle lay flat. Back in the conference room I noticed a property map of the area with a few squares labeled shumway. Those were old garden plots about a mile from the mill, Logan said. He grows watermelon and squash there for his family. The produce was perfectly safe to eat. Once or twice, on that rare weekend when he isn’t chopping firewood at his cabin or branding cattle for his folks, he has sold the leftovers from a roadside stand.

III. THE MINES

At the peak of the uranium boom, back when mill waste was something you mixed into the concrete foundations of urban residential projects, Moab proclaimed itself the Uranium Capital of the World. The Mormon settlement has since rebranded itself as an adventure-sports mecca, a Shangri-la for the CamelBak class. Mountain-bike paths wander through old prospectors’ claims, and kayak shops have replaced the miners’ camps, although you can still see one uraniumaire’s hilltop mansion, now a family restaurant, overlooking the north side of town.

I drove through Moab to visit a constellation of zombie mines in the nearby La Sal Mountains, where the timber trucks and hoist houses stand intact, waiting for the industry to turn around again. Some were fenced off; others weren’t, and I was able to poke around unlocked offices and equipment sheds filled with discarded bags of barium chloride, a toxic precipitant.

Yet the mines were somehow disappointing. I realized that, however ridiculously, I’d expected them to emanate green or yellow halos of residual power — or something — as in my childhood visions of the atomic West. That’s the problem with radioactivity: you can’t see, smell, or taste it. This imperceptibility lends itself to irrational fears, or else to blissful ignorance, depending on whom you ask. I wanted to know what was really out there. So I arranged to visit some Colorado mines with a radiation expert.

Mine cart tracks inside the Hummer Mine

The next afternoon, beneath the rumpled white ridge of the Rockies, I pulled my car into the Montrose Regional Airport pickup zone. Lucas Hixson emerged from the baggage claim in aviator shades and a green felt cowboy hat, a lit cigarette protruding from his long Dostoevskian beard.

“I brought you a gift,” he said, digging into a duffel bag to retrieve a small piece of graphite collected at the site of Fermi’s second Chicago Pile. Lucas had explored the area last year on one of his gathering trips. “Don’t worry,” he said. “This one’s not hot.”

After a disillusioning teenage stint in the Army, Lucas entered and dropped out of college, then stumbled into a three-year apprenticeship in gamma ray spectroscopy that determined the course of his life. Radiation was his calling. He opened a one-man lab for towns with nuclear waste problems, and had lately expanded his activities into giving safety courses inside the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone and filing FOIA requests for unreleased Manhattan Project paperwork. As we drove deeper into Colorado mining country, I asked how, as a thirty-year-old with a growing career, he reconciled his work with the risks of exposure.

“My mom used to say, ‘There are old pilots and there are bold pilots. But there are no old, bold pilots,’ ” he told me. His crusade had taken him to some of the world’s most noxious sites, and despite the tangled nest of wires and electronics he carried in his bag to monitor radiation exposure, he sometimes worried about heavy metal poisoning and other professional hazards. Still, he claimed he’d never retire from environmental work. “I think about literally nothing else,” he told me. “What else is there to think about?”

We drove into Paradox Valley, where we planned to bivouac beneath a giant cottonwood on the grounds of a former hippie commune. I parked the car against the far canyon wall, by a Quonset hut filled with canvas sails and sheets of metal. The unmistakable bouquet of harvest-ready marijuana wafted from the farm next door.

Our guide for the weekend, an environmental activist named Jennifer Thurston, walked over as we were stretching our legs. “You’re early,” she said, laughing. “Go for a walk!” While Jennifer finished preparations for the next day’s fieldwork, Lucas and I hiked halfway up the mesa to watch the sun set between the rosy clouds and the rosy cliffs beneath them. “This is my church,” Lucas kept saying, arms outspread. Hundreds of one-man doghole mines lined the valley walls.

The next morning we suited up with an assortment of handheld radiation counters, piled into an ’87 Toyota camper van, and drove up the valley. Our first stop was a Department of Energy mine. The land was public, even if the mining rights weren’t, so anyone wearing the proper protection could enter. It was beyond decrepit. All the copper had been stripped from the hoist house, which was filled with pack-rat holes and feces. The headframe above the shaft was a towering thumb of rust. As we circled the site, our counters clicked excitedly. My belt dosimeter began to flash and vibrate, meaning that I was receiving a dose of radiation about twenty times higher than the baseline we’d marked at Jennifer’s. (All radiation exposure must be measured against an area’s ambient background noise.) Lucas raced happily from one rock heap to the next, swinging his scintillator like a censer and calling out the hottest spots, which looked exactly like the area surrounding them. “Visiting a uranium mine without a radiation detector is like seeing in black and white,” he said.

“Who leases this mine?” I asked, positioning myself away from any rocks Lucas described as “spicy.”

Jennifer snorted. “My state senator.”

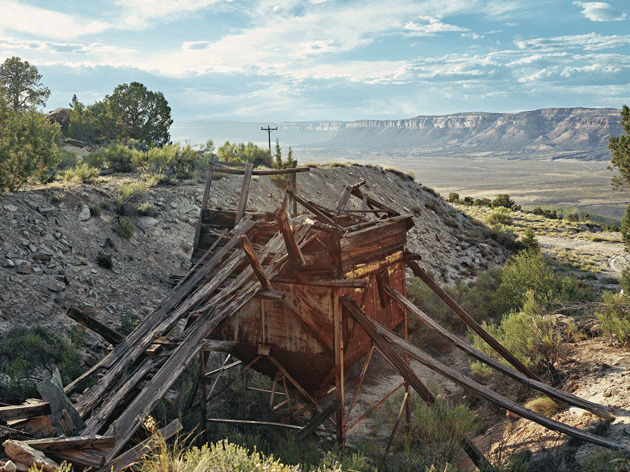

It was one thing to peer into the abyss of a mine shaft while standing safely above. I’d asked for the immersive experience. So we drove to the Hummer, a private mine whose large wooden hopper, in an advanced and elegiac state of decay, dribbled crumbles of wood down the hillside where, once upon a time, trucks were loaded up with ore. The mine’s tunnels stood irresistibly open. Jennifer agreed to wait outside the property and send for help if we didn’t come out in twenty minutes.

The first portal we approached was partially collapsed. In the second, we found ourselves rebuffed by a tunnel of crumbling slabs. A third entrance struck me as equally unsound, but the supporting struts were firm, so we shuffled inside. Right away, we ran into a hole that stretched across our path and dropped at least twenty feet into blackness. Someone had flung a four-by-four beam across the gap.

“How’s your balance?” Lucas asked, wiggling his eyebrows. He strode nimbly across. I inched over the beam with less grace, grasping at the wall with both gloved hands and trying not to look down. On the other side of the gap my dosimeter began to pulse, and our Geiger counters crackled like oil in a hot pan. The sunlight vanished as we descended into the cliff face, our flashlights casting dim roundels along the tunnel walls. Beneath us, the ground was thick with guano, and sleeping in the crevices above our head were dozens, if not hundreds, of small brown bats.

It occurred to me somewhere in that tight darkness that I had been thinking about radioactivity in overly abstract terms. I’d imagined I understood the slow-moving tragedy of those Westerners poisoned by atomic-test fallout or by the seepage of mill waste. I’d read books about the generation of miners wiped out by leukemia, lung cancer, and kidney failure while perfidious company overlords rebuffed their concerns under the banner of national interests. But I hadn’t worried about my own exposure. Those tragedies seemed part of a bygone world. Besides, I wasn’t a miner or mill worker, only a tourist. I’d be fine.

Deep in the Hummer, these rationalizations struck me as profoundly insane. I was swimming in poison. My dosimeter pulsed frantically — twenty, thirty, forty times background — at the presence of a spectral bogeyman not even experts know much about. Early A.E.C. officials estimated that a miner in an unventilated mine would receive his maximum dose of radon gas in about two hours, but outside a laboratory it is impossible to precisely gauge one’s exposure to the varieties of ionizing radiation, and no one can say what amounts to a truly safe dose of any of them. I kept tugging on my face mask as we walked, since Lucas had warned me that the worst radiation damage comes not from what you touch but from internalized radon daughters: the isotopes of polonium, bismuth, and lead that form inside your lungs as radon decays, firing alpha particles — the atomic equivalent of buckshot — into your tissues and the mutable strands of your DNA for as long as you live. With every breath, I pictured a double helix, spongy with holes.

At the far end of the tunnel Lucas scrambled into a room I wouldn’t enter. The ceiling had collapsed. Where once there had been a narrow passage now stood a spacious gallery of glimmering rock, giving onto a part of the mine that seemed to have been abandoned one day over lunch break. I shone my light over work gloves and rivets covered in four decades of dust. An ore bin filled with rocks registered 5 million gamma counts per minute according to Lucas’s scintillator, a whopping 700 times background, and nearly the upper limit of his detector. He wanted to go farther. I’d seen enough.

The entrance of the Hummer Mine

Back outside, Lucas held his Geiger counter up to his face. This was apparently a favorite pastime of rad heads, but even Lucas seemed startled by the figure: around fifty times background, the result of the radon progeny that had caught on condensation in his beard. “Wow,” he mused, taking a selfie with the counter against his mouth.

“You might want to think about shaving,” Jennifer said.

We ate a packed lunch outside an old prospector’s dugout in a neighborhood of mines beyond Disappointment Valley, stepping lightly over ashy roses of cow shit. Mines were everywhere. Some had been lavishly transformed into flowering meadows, but those were the exception. Most were dumps. Colorado’s unevenly enforced patchwork of state and federal regulations gives owners broad discretion in matters of upkeep, and even reclaimed sites, set under Lucas’s probes, proved to be more radioactive than their surroundings. We found hot zones next to farms, bisecting grazing paths and arroyos, each an unguarded, invisibly tainted ruin.

The next day I stopped into the visitor center in Naturita. Naturita is the nearest surviving town to Uravan, a Manhattan Project company town so toxic it had to be demolished down to its last boardinghouse. I wanted to ask about some petroglyphs I’d heard were accessible along the highway. The woman there didn’t know much about petroglyphs, but she was pleased to inform me that uranium mining was not at all dangerous. How else could I explain the fact that some old miners were in better shape than she was? Besides, she said, God takes you when he’s ready for you. Like a lot of people in Naturita, she was waiting for the mines to come back.

IV. THE BOOMTOWN

The Colorado Plateau is armored to the south by the red cliffs of the Mogollon Rim, to the west by the Wasatch Range, and to the north by the Uinta Mountains, a stretch of upturned shelf the color of béton brut. I drove across the Uintas into Wyoming, where the richest uranium reserves in the country are still buried. There was a lot of time to think.

Wyoming is America’s least populated state. It may therefore be as good a home as we’re likely to find for the future of nuclear fuel. Since the 1990s, most of our modest domestic production has taken place at remote “in situ leach” sites, many of which could be found along my route, in the bare white basin of Converse County. At I.S.L. mines, uranium is leached directly from underground well fields, diesel-pumped to the surface, and vacuum-dried on-site, obviating the need for conventional mills. The industry touts it as an efficient way to do small-scale business in a low-demand economy until the long-predicted nuclear-energy booms in India and China finally arrive. The risks to workers are low and there are no large tailings piles to bury, as the waste stays underground. On the other hand, I.S.L., like conventional mining, tends to pollute groundwater with radioactive materials and heavy metals. (At least one state — Texas — has responded by relaxing water-quality standards.) Nevertheless, I.S.L. dominates the industry, in some years accounting for up to 95 percent of all domestic production.2

It’s a long way from Alvin Weinberg’s forecast of a nuclear-powered planet. But his 1971 speech, delivered at the height of nuclear ascendancy and just before the long decline, ended on a more tentative note, and it’s the conclusion that is more often quoted and remembered:

We nuclear people have made a Faustian bargain with society. On the one hand, we offer — in the catalytic nuclear burner — an inexhaustible source of energy. . . . But the price we demand of society for this magical energy source is both a vigilance and a longevity of social institutions that we are quite unaccustomed to.

Peaceful nuclear energy would require a “military priesthood” to maintain “eternal vigilance” over its misuse, Weinberg believed, the same kind of demands that are made on society by nuclear weapons — for an even longer duration. By the time I reached the final stop on my road trip, not fifty years after Weinberg’s speech, it was clear that neither Faust nor Mephistopheles had upheld his end of the bargain.

Byron Seeley stands next to an abandoned barracks at Western Nuclear in Jeffrey City, Wyoming

Jeffrey City was founded in the Thirties as Home on the Range, a general post for wandering ranchers. It was renamed in 1957 to honor C. W. Jeffrey, a Rawlins physician who fronted $250,000 to the state’s first uranium speculator. A company trailer town appeared, followed by a large mill. A grid of residential streets, miners’ barracks, and modest houses went up, all owned and managed by Western Nuclear. During the commercial boom in the 1970s, more than four thousand people called Jeffrey City home. There was a movie theater inside a Quonset hut, a K–12 with a co-ed basketball team, even a bowling league.

Then came the crash, followed by downsizing and divestment. By the mid-Eighties, reporters were calling Jeffrey City postapocalyptic, and I saw no reason to revise that description when I arrived. I passed through a fringe of nebulous rust piles on the drive in, and several buildings that looked as though they’d been hastily stripped for parts. Main avenues like Jackpot Drive had been reduced to plots of weedy rubble.

One exception to the disrepair was a mural-covered former gas station that proved to be the live-in pottery studio of Byron Seeley, a gentle soul who didn’t have strong feelings about uranium one way or the other. I liked Byron right away. He wore a shapeless cowboy hat and rain boots covered in daisy-print duct tape, and told me candidly that he drank too much, missed a woman’s touch, and had recently shaved his beard: “I used to be a hairy potter, now I’m a mad potter.” A fine ceramist, Byron had grown up in a family of ranchers but managed to escape that inheritance when he discovered pottery in high school. He bought the shuttered Standard Oil station in Jeffrey City for five grand, joining fifty-odd other hermits settled here — Vietnam vets, single moms, and seasonal truckers, self-styled exiles who detest rent and taxes. Byron showed me the .22 with which he shot unfired pots and tin cans for sport. For $40 I bought two of his most beautiful yunomi teacups. “You been to the bar?” he asked.

We walked across the street to the Split Rock Bar and Café, which serves as Jeffrey City’s restaurant, trading post, town hall, boxing ring, gas station, and singles club. It was the kind of place where the jukebox is flanked by mounted deer heads and old barflies like Byron are asked to serve themselves. From behind the bar he introduced me to some of the town’s more bibulous citizens, and to his good friend Billy Swick. Billy grew up in Jeffrey City, and had returned as a young man to watch it wither away. “Most of my family came out of the underground mines,” he said. “That’s why I come back — to go underground and go to work.” He’d arrived just as layoffs began. Now there was no work. The mine shafts were long since flooded.

Billy blamed a bipartisan cabal of U.S. presidents for the area’s high unemployment, but he singled out Ronald Reagan for failing to secure domestic uranium jobs after Three Mile Island and Chernobyl. “They didn’t want to have to deal with that EPA shit,” he said.

Veronica, the bartender, nodded. “It killed our towns,” she said.

“You’re looking at a real live living ghost town,” a guy in a camo baseball cap mused.

In Jeffrey City, it was hard to see anything that resembled Weinberg’s priests, those dispassionate guardians of the nuclear flame. Instead, I was reminded of a famous line of Wallace Stegner’s: “The West has been raided more often than settled, and raiders move on when they have got what they came for.” Raiders have come West for land, for gold, for oil. Raids are entwined with the region’s strange and persistent mythos, according to which the earth is inexhaustible, its cavities filled with gifts from a loving God that belong to whoever is strong enough to claim them. The atomic age was the pinnacle of that long history. Even as Weinberg promised “an all but infinite source of relatively cheap and clean energy,” wide swaths of the country were being wastelanded by mills and mines, most egregiously on Native American soil. (More than five hundred mines await reclamation in the Navajo Nation alone.) Even in relatively affluent cities such as Moab, which markets itself as a natural wonderland, a $1 billion mill cleanup — among the most expensive in American history — has been dragging on for decades along the banks of the Colorado River. Uranium turns conventional truths upside down: Here a man might outlive the town where he was born, or make a home on soil poisoned by its own surfeit.

Byron and I took a drive to check out one last tailings repository outside of town, although not before he spilled his bag of bullets all over my car. (He’d brought the .22 to shoot road signs.) It was a plot of forgotten history, miles from anywhere, amid vast knucklebones and vertebrae surging from the ground. I couldn’t find the white tombstone I’d seen at other piles testifying to the size and toxicity of the materials buried there. Byron drank punctuationally from a bottle of vodka mixed with pink lemonade, and when we got back to town he said he wanted to show me something.

We slipped past no trespassing signs into the barracks of Western Nuclear, where single miners and mill workers had once slept — “bachelor pads,” Byron called them. Now the windows were blinded with plywood, the insides gutted by hobo fires.

“If anyone’s here, we mean you no harm!” Byron shouted into the gloom. He gestured me in with the handle of vodka and we made our way to a staircase in the building’s dark foyer, where he pointed to a multicolored patch of light on the wall. As my eyes adjusted to the darkness, the patch congealed into a picture. It took me a minute to figure out what was going on: It was a camera obscura. Some copper thief had extracted a wall socket by the front door and a shaft of sunlight was penetrating the oversized pinhole left behind, casting an inverted image of Jeffrey City against the wall above the stairs. At the bottom of the picture was a fat blue strip of sky, here was a telephone pole, there the Quonset movie palace and, as uncanny firmament, the burned and bleached Wyoming dirt. The lines were hazy. It was like something you’d glimpse in a crystal ball. For a while we just looked at it, Byron and I, sharing a vision of the boomtown as seen from beneath the earth, unmoored from time, looking almost lively in the blur.