Among the folk invited to Tony’s wedding were the Hardcomes o’ Climmerston — Stephen and James — first cousins, both of them small farmers. With them were their intended wives, two young women of the neighborhood, both pretty and sprightly maidens.

Each pair was well-matched, and unlike the other. James’s intended was called Emily, and both she and James were gentle, indoor people, fond of a quiet life. Stephen and his chosen, named Olive, were of a more bustling nature, fond of racketing about. The couples had arranged to get married on the same day, not long thence.

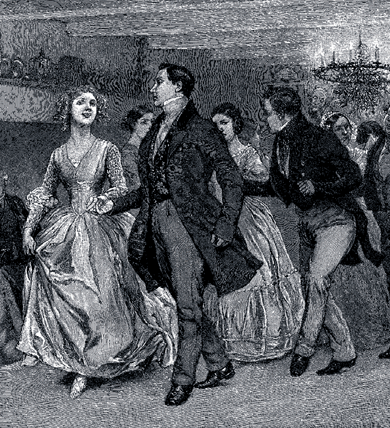

They danced with such a will as only young people in that stage of courtship can dance; and it happened that as the evening wore on James had for his partner Stephen’s plighted one, Olive, at the same time that Stephen was dancing with James’s Emily. The later it got, the more did each of the cousins dance with the wrong girl, and the tighter did he hold her as he whirled her round; and, what was remarkable, neither seemed to mind what the other was doing. After a particularly warming dance, the two young men looked at each other.

They danced with such a will as only young people in that stage of courtship can dance; and it happened that as the evening wore on James had for his partner Stephen’s plighted one, Olive, at the same time that Stephen was dancing with James’s Emily. The later it got, the more did each of the cousins dance with the wrong girl, and the tighter did he hold her as he whirled her round; and, what was remarkable, neither seemed to mind what the other was doing. After a particularly warming dance, the two young men looked at each other.

“James,” says Stephen, “what were you thinking of when you were dancing with my Olive?”

“Well,” said James, “perhaps what you were thinking of when you were dancing with my Emily.”

“I was thinking,” said Stephen, with some hesitation, “that I wouldn’t mind changing for good and all.”

When they parted that night the exchange was decided on. Thus it happened that on Sunday morning, in church, there was no small amazement to hear them coupled the wrong way.

The two couples lived on for a year or two ordinarily enough, till the time came when these young people began to grow a little less warm to their respective spouses, as is the role of married life; and the cousins wondered more and more in their hearts what had made ’em so mad at the last moment to marry crosswise as they did. They said very little about this mismating, though sometimes Stephen would look at James’s wife and sigh, and James would look at Stephen’s wife and do the same.

So things remained till one summer day they went for their yearly outing together. When they reached Budmouth-Regis they walked two and two along the velvet sands. They looked at the ships in the harbor; went up to the Lookout; had dinner at an inn. As evening drew on they sat on the esplanade, and listened to the band; and then said, “What shall we do next?”

“Of all things,” said Olive, “I should like to row in the bay!”

“So should I,” says Stephen, his tastes being always like hers.

Stephen’s wife hated the sea, and couldn’t bear the thought of going into a boat. James, too, disliked the water. James and Emily agreed to remain where they were sitting, and enjoy the music, while they watched the other two hire a boat just beneath.

The band played; people strolled up and down; and Stephen and Olive shrank smaller and smaller as they shot straight out to sea.

Stephen’s wife and Olive’s husband waited, with more and more anxiety. But no little yellow boat returned. The night advanced. Emily was so worn out that James felt it necessary to conduct her home; there was, too, a chance that the truants had landed in the harbor on the other side of town, or elsewhere, and hastened home in the belief that their friends would not have waited so long.

However, Stephen and Olive were not at their homes. Emily and James went to their respective dwellings, the next morning returning to Budmouth.

In the course of a few hours some young men testified to having seen a man and woman rowing in a frail outrigger straight to sea; they had sat looking in each other’s faces as if in a dream. In the evening the sea rose somewhat, and a cry spread through town that two bodies were cast ashore several miles eastward. Inspection revealed them to be the missing pair. It was said that they had been found locked in each other’s arms; their features still wrapt in the same dreamlike repose.

From “Wessex Folk,” which appeared in the March 1891 issue of Harper’s Magazine. The complete story — along with the magazine’s entire 167-year archive — is available online at harpers.org/fromthearchive.