When you consider the savagery of your run-of-the-mill fairy tale, our use of the term to connote “romance” or “idealization” smacks of nothing more than romance and idealization — a semantic circle of willful delusion. Take “The Juniper Tree,” by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. A woman longs for a child, gets pregnant, gives birth to a son, and dies. The father remarries. One day, while the little boy has his head in a chest filled with apples, his stepmother slams down the lid, decapitating him. “Maybe I can get out of this,” she thinks. She ties the boy’s head back on with a scarf, convinces her daughter that she killed him, and cooks him into a stew. The truth comes out when a bird, channeling the boy’s spirit, crushes the stepmother with a millstone. It’s gruesome. But the story’s most grotesque feature is this mild sentence about the first wife: “Then she had a child as white as snow and as red as blood, and when she saw it, she was so happy that she died.”

“The Juniper Tree,” by Andrea Dezsö, whose silhouette drawings are featured in The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition, translated by Jack Zipes (Princeton University Press)

Barbara Comyns’s novel THE JUNIPER TREE (New York Review Books, $15.95), a treasure from the 1980s reissued with an introduction by Sadie Stein, picks up the Grimm notion that an excess of maternal happiness can prove fatal. Then it goes a step further, suggesting that a mother’s happiness could very well depend on other people dying. Our narrator is Bella Winter, the white mother of a mixed-race daughter. (All that she recalls of the father, a one-night stand, is his red velvet jacket.) Bella is a dark-haired, glittering-eyed beauty with a scar on her left cheek from an automobile accident. She gets a job in an antiques shop and becomes enmeshed with a wealthy, art-collecting couple, Bernard and Gertrude. Bernard makes Bella his protégée and takes her to films and the theater. She spends long weekends at their estate, picnicking with Gertrude in the garden. Shortly after giving birth to a son, Gertrude dies “of a haemorrhage amongst other things.”

Comyns’s prose is vivid and charmingly hurried. “It was wonderful to be in the quiet square with the sleeping cars humped outside the houses like sleeping animals, elephants perhaps, one could almost hear them breathing.” (A lesser writer would have cut one “sleeping,” or worse, consulted the thesaurus.) In an ingenious modern revision, much of the novel is devoted to the period before Bella and Bernard marry. She enjoys working in the shop and is reluctant to give it up. She does everything possible to forestall the marriage, hiring nurses and nannies and cooks, but they’re all inadequate, and anyway, she’s smitten — “Besides almost worshipping Bernard I had this very strong physical love for him.” At last she accepts her fate. Comyns sprinkles bread crumbs for the careful reader:

When I told Mary that I was marrying Bernard after all she smiled and said she had already guessed. Although she didn’t approve, she felt it was a thing I had to go through even if it crushed me.

Bella may be a jealous stepmother — Bernard proves unable to get over his dead wife — but she is hardly wicked. Even a good mother can make a terrible mistake. The Grimm story is about evil, revenge, and justice — an eye for an eye — but The Juniper Tree is about accidents, damage, and repair. Comyns gives her heroine and her daughter something shocking in the annals of fairy tales — a happy ending.

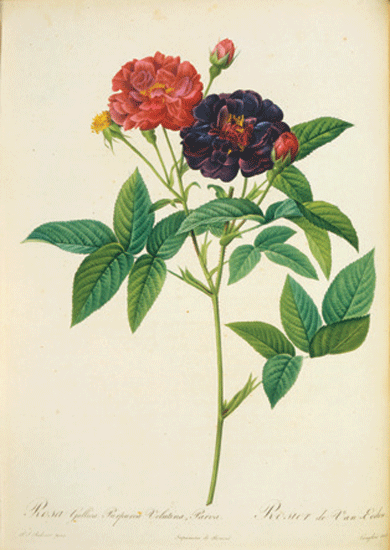

Rosa Kamtschatica, by Pierre-Joseph Redouté

© The LuEsther T. Mertz Library, New York Botanical Garden/Art Resource, New York City

Near the start of Gerrick D. Kennedy’s PARENTAL DISCRETION IS ADVISED: THE RISE OF N.W.A. AND THE DAWN OF GANGSTA RAP (Atria Books, $26), we meet, too briefly, Verna Young, the mother of Andre Romelle, aka Dr. Dre. Verna loved music. Her LP collection was filled with Marvin Gaye, Sly Stone, Parliament-Funkadelic, Isaac Hayes, James Brown, and Earth, Wind & Fire. When she got home from work, she’d put a record on the turntable before switching on the lights. As a teenager she had performed with a musical group, and when her son was that age she designed and sewed the costumes his dance team wore to pop and lock. She bought him his first mixer and let the neighborhood kids hang at her place. On the nights that Dre deejayed at Eve’s After Dark, Compton’s all-ages club, Verna set an alarm for one in the morning so she could pick him up after his set.

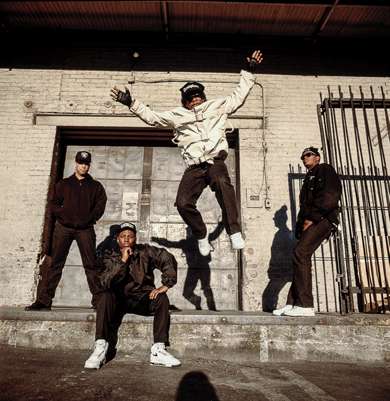

“N.W.A., 1990,” a photograph by Lynn

Goldsmith.

Getting the band together is usually the fun part of the story, and Parental Discretion is no exception. By the time Dre, Eazy-E, Ice Cube, MC Ren, and DJ Yella have gone their separate ways, the plot has devolved into standard pop tragedy. Yes, N.W.A. will go down in history for their aggressive, original sound, their lyrics about race and crime, and the authorities’ attempts to censor them. But the dis tracks and lawsuits were about the same thing they always are: money. Eazy, the first rapper to own a successful record label, was making lots of it; the other guys were getting screwed. As Dick Griffey, the founder of Solar Records, said of the artists on the Ruthless roster: “They had the worst contracts I had ever seen in the history of the record business.”

Kennedy leans on interviews with Ice Cube and the D.O.C., but Eazy is the most colorful character. He fronted a group whose single “Fuck tha Police” became the unofficial anthem of the LA riots but attended the Rodney King trial to support Theodore Briseno, one of the police officers involved in the beating. “Sure, I’ve seen that little stomp Briseno does on the video, and I’m not saying it’s justified,” he told the Los Angeles Times. “But we don’t know what it was about, do we?” He bragged on a solo album, “I may be a woman beater, but I’m not a pussy eater,” and once offered encouragement to a man on the street who was hitting his wife: “Beat that bitch’s ass, beat her fucking ass.” Kennedy notes that he also gave money to the Make-A-Wish Foundation and City of Hope, and took busloads of kids to Six Flags. Okay, whatever.

“Forms & Records No. 6,” a photogram by Doug Fogelson. Courtesy Sasha

Wolf Projects, New York City

In 1988, the only major label willing to distribute N.W.A.’s debut was Priority Records, whose biggest act was the animated quartet of Motown cover artists known as the California Raisins. Kennedy gives a nuanced account of the group’s vexed relationship with their manager, Jerry Heller, and includes players who were sidelined in the recent biopic Straight Outta Compton: J. J. Fad, the group whose hit “Supersonic” helped Ruthless score a distribution deal, as well as Dee Barnes, Michel’le, and Tairrie B, three women whom Dre assaulted. He covers the rise of Snoop, the crimes of Suge Knight, and Eazy’s death from AIDS-related complications, following the trail to 2016, when the surviving members reunited at Coachella. The biggest surprise of the book comes early on, in a vignette about young Eazy’s career as a crack dealer. Whenever someone paged him — an 8 for an eight ball, a 12 for half an ounce — he’d walk to the corner of Caress Avenue and Alondra Boulevard, in his white T-shirt, tube socks, and Dickies, to close the deal at a pay phone. “The phone is still there today, dusty and unused,” writes Kennedy. It must be the last pay phone in America.

Photograph of J. J. Fad, 1988. Courtesy Juana Sperling

Dr. Dre didn’t like “Fuck tha Police” when Ice Cube first showed him the lyrics. He wanted to make fun songs that you could play at a party. As Kennedy explains: “Dre’s attitude about the song changed when he and Eazy got busted by some cops for shooting paintballs at people and the officers put guns to their heads.” Rhymes like “police think they have the authority to kill a minority” haven’t aged a day. But as I learned from Jacqueline Jones’s GODDESS OF ANARCHY: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF LUCY PARSONS, AMERICAN RADICAL (Basic Books, $32), “shoot to kill” was once the Chicago Police Department’s policy against whites too. Between 1870 and 1920, homicides by police increased fivefold. Much of this violence was directed against striking or protesting workers. The bullets, however, did not always find their intended targets. An internal investigation into the Haymarket riot of 1886, which left seven officers and four workers dead, found that “the police emptied their revolvers, mainly into each other.”

The events of Haymarket made Lucy Parsons a widow — her husband, Albert, was hanged alongside three other anarchists in a spectacular miscarriage of justice. The two had met in Waco, Texas, shortly after the Civil War. Albert, a white man who as a teenager had served on the Confederate side, was climbing the ranks of the Republican Party by agitating for African-American rights; Lucy was born a slave in Virginia and was brought west in 1863. (During the Civil War, some slaveholders migrated to Texas, thinking that the Lone Stars would never bow to the Union.) They married during a brief period when interracial unions were legal and then moved to Chicago, where they embraced socialism, trade unionism, and anarchism. Both rejected mainstream political parties and the ballot box, refusing to vote even at Socialistic Labor Party meetings. (They thought that groups should talk until achieving consensus.) Lucy was a fierce orator and writer who rejected reform and charity (“hush money to hide the blushes of the labor robbers”) and roused large crowds with revolutionary talk (“Learn the use of explosives!”). She wore a black dress and, around her throat, a gold necklace with a gallows charm.

Photograph of Lucy Parsons by August Brauneck. Courtesy

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Goddess of Anarchy is meticulously researched. Yet Parsons, as a character, remains inscrutable. Questions linger. Why did she say so much on behalf of exploited whites and almost nothing about black workers? Why did she tell reporters that she was Mexican and Indian? Why did she have her son, whom she had once paraded before the press, draping him in a red scarf and calling him “my brave little anarchist,” committed to a mental hospital? She claimed that he threatened to stab her with a knife, but she may have been more annoyed that he wanted to enlist in the army. (At the trial, he accused her of wanting to steal his property.) Albert Jr. languished in the Elgin Asylum for twenty years, abused by the guards and by other inmates, until he died of tuberculosis. Parsons criticized Emma Goldman for equating anarchism with sexual liberation, and insisted that “family life, child life” were the “sweetest words,” but her own maternal instincts were straight out of a Grimm fairy tale.